What does Rowan Williams’s resignation mean for American Anglicans?

By Daniel Schultz

This article was updated on 4/23/12

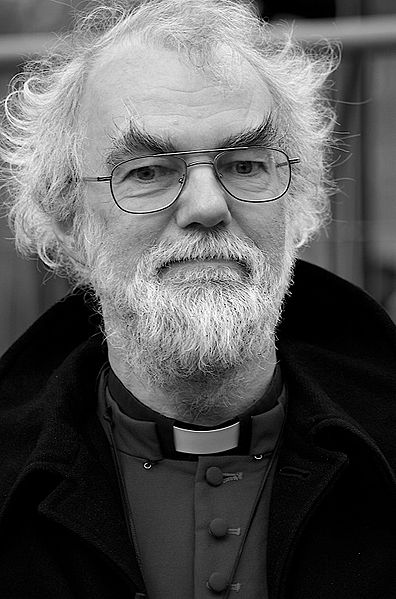

Word reached us lately that the eyebrows of the Most Rev. Rowan Williams, Archbishop of Canterbury, had decided to step down at the age of 61, apparently taking the attached primate with them into an early retirement, or at least a return to the academic life as Master of Magdalene College. Perhaps not coincidentally, a little while later it came out that the Church of England was set to reject the Anglican Covenant, Williams’ pet project to bind together the far-flung theologies of the Anglican Communion in some way or another. Nobody was ever quite sure how. In any case, a defeat like this must have been hard to bear, even for Williams’ ordinarily indefatigable—not to mention gravity-defying—eyebrows. Little wonder he (and they) decided to light out for Oxford (update: Cambridge, per the comments) while the getting was good.

What does Williams’ departure and the arrival of his successor mean for the average Christian in the United States? As with so much in the world of the church, the answer is: it depends.

At the moment, the bookmakers favor John Sentamu, the Ugandan-born Archbishop of York, to replace Williams. But it’s not by much: Sentamu averages about a 50-50 shot from the houses willing to accept a wager on his ascension. That seems like a good way to describe Sentamu’s candidacy, actually. He has pluses and minuses. On the upside, he has a compelling personal narrative—Sentamu was a judge in Uganda, and narrowly missed being executed by Idi Amin—and he would be the first black Archbishop, making his selection historic. On the other hand, he has come out against marriage equality firmly and repeatedly, which may put him at odds with David Cameron, the British Prime Minister who must submit a list of candidates for Queen Elizabeth’s approval, and who faces pressure from British society to move its marriage laws in the same direction as other western European nations.

Sentamu is prominently identified with the evangelical camp in the divided communion, which limits his ability to play the role of peacemaker. He is also identified with the conservative movement in England, an enthusiastic contributor to Rupert Murdoch’s Sun on Sunday. He is a very enthusiastic contributor. Again, perhaps not coincidentally, Sentamu is well known as a self-promoter, a bishop on the move, which may limit his attractiveness as a candidate.

It’s not entirely unjustified to think that Sentamu would be bad news for the Episcopal Church in the USA, which is facing its own divisions over the inclusion of gays and lesbians. Sentamu took to the floor of an ECUSA meeting in 2006 to accuse the American church of breaking friendship with the wider communion by electing the openly gay Gene Robinson bishop of New Hampshire, and demanded that the Episcopalians acknowledge that it was “inherently wrong to ordain a gay man as bishop.” That pleased American conservatives, some of whom have left the ECUSA to affiliate with more conservative churches in Uganda, among other places. But Sentamu has also been a vocal opponent of the “kill the gays” bill in his home country.

And it’s not clear what Sentamu could do to hurt the American church. The ECUSA is already autonomous for all practical purposes. At the most, a hostile Archbishop could freeze the Americans (or the Canadians, who have also pushed to extend the welcome of gays and lesbians in the church) out of Communion events and impede their ability to work with global church partners. That’s painful, but basically symbolic. In all likelihood, a Sentamu primacy would be something of a wash for the North American churches: frosty, sometimes hostile, but realistically irrelevant.

If the nominee is not Sentamu, then what? The names thrown about conventionally include Richard Chartres, the Bishop of London. Chartres has connections with Prince Charles, and has officiated at several ceremonies for the royal family. That might cut both ways: as Britain runs up to the Queen’s Jubilee year, its leaders might nominate a potted plant for Archbishop if they thought she would like it. But if Chartres becomes identified as Charles’ candidate, he might be sunk. Besides, Chartres’ eyebrows are even older than Williams’, and will face mandatory retirement before long. As well, Chartres has done a poor job on the question of ordained women as priests in the Church of England, another hot-button issue Parliament may want to avoid. At least he was able to pluck the Diocese of London from the mire surrounding the Occupy protests at St. Paul’s cathedral.

Graham James, Bishop of Norwich, and Nicholas Baines, Bishop of Bradford, are among other names that have surfaced. James is older, but may be a reconciliative caretaker until the next long-term primate comes along. Baines is younger, which may help (or hurt) his chances. Or it might be somebody truly out-of-the-box. Bishops from the British Commonwealth are eligible, which means that the next Archbishop could come from Canada, Africa, India, or Australia. But really at this point, things become murky. If the candidate isn’t Sentamu, it could be anybody—and anybody will come as a surprise.

So again, what does any of this mean for the average churchgoer in the United States or Canada?

Not much, on one level. Despite Williams’ nosebleed-high ecclesiology, most of the practical work of the church takes place on a much lower level. Williams met often and happily with Pope Benedict XVI, even as the former Cardinal Ratzinger sold him out by poaching Anglican churches hellbent on conservative orthodoxy. For Williams, that was ecumenism. For the rest of his flock, ecumenical work takes place on the level of partnerships formed between provinces, dioceses or even individual congregations.i

Many American institutions do important ministry with groups in Sudan or Recife or other places around the world. Those connections will continue largely without regard to who leads the Communion, or whether the Covenant is in place or not. The relationships may be more or less strained depending on how things play out, but they will continue. And as it came out in Gene Robinson’s journey to the bishopric, there’s not much of anything the Communion can do to change the behavior of a determined church.

The meaning of Williams’ departure, then, will largely depend on how important you think it is for Christianity to be a coherent movement. Williams’ great work—and great failure—was to try to get the Anglican communion to coalesce around a single vision of what it meant to be a church.

Whether this project flopped because of Williams’ poor leadership, or because it was an impossible task to begin with, will surely be the source of debate for a long time to come. Critics charge that Williams was too fond of the kind of clerical authoritarianism espoused by the current Pope. Others say he misunderstood the work of trying to forge unity in the midst of modern diversity. He certainly was happy to throw some parts of the church—including his good friend Jeffrey John—to the wolves if that’s what it took to maintain unity. But the Archbishop of Canterbury has always been a weak position in modern times, depending on voluntary assent and moral suasion, rather than the ability to impose policy by fiat. With thirty-eight provinces and six extra-provincial churches, each working in a radically different context and each with its own relationships between and outside the group, it’s amazing that they can agree on what to have for dinner when they all come together, let alone social, economic, or theological policy.

And that’s just the primates. Within each province, there are dioceses with bishops who are more or less independent-minded, depending on their bent and their political commitments, and within the dioceses, there are parishes, and at the most granular level, there are 80 million adherents of this thing called the Anglican Communion, and their eyebrows too. Historically, what’s kept all these people together has been their common worship style, and The Book of Common Prayer…and that’s about it. They haven’t even been able to agree on who heads the church in hundreds of years.

Which may be as it should, or not. The Christian church—not the institution, but the body of people that has continued over time—has been fighting it out about diversity and unity since the very beginning. As Giles Fraser points out, the very word pontifex, used to describe the pope and other summary leaders of churches, means “bridge-builder,” as in someone who could connect divided parts of the community. And the very first Archbishop of Canterbury was sent from Rome with the mission of bringing the intractable English church back into the Catholic fold. He muffed the job.

If you believe, as most Americans do, that the upper reaches of the church don’t have much to do with the ground floor, the next Archbishop of Canterbury will have mostly trivial interest to you. Perhaps it will be John Sentamu, and the ECUSA is in for the deep-freeze. Perhaps it will be a conciliator or a caretaker. Perhaps it will be someone with an even more lush and vigorous patch of Muppet fur insulating his brows from the slings and arrows of church leadership. Who’s to say? But Easter will come, just as it did this year. There will be babies to baptize, teens to confirm, crappy church coffee to be drunk (maybe good sherry if you’re in the right congregation), and ministry to be done, regardless of who fills Williams’ seat.

But if you believe, as many Americans do, that it is of the utmost importance to speak with one voice on women in ministry, or the place of gays and lesbians in the church—if you believe that without a common creed and ethics and way of reading scripture, there’s no point in calling it a “church”—well then, you’re in for a very interesting six months or so. It’s unlikely that you’ll get a champion of orthodoxy like Benedict, and probably not such a fierce champion of unity-at-all-costs as Williams. You may have to face the same uncomfortable ideas that the rest of us are confronted with: that there is no single voice for Christianity, that Christ’s prayer “that they may all be one” is and always has been a fond wish and ardent desire but never a fact on the ground, that Christianity as a world movement has not produced a standard culture but has shaped and been shaped by many different cultures in many different ways, to the detriment of its coherence. But at this point, who the hell knows? You may find somebody who can bring it all back together, or (more likely), you may find another weak leader committed to togetherness in principle but unable to do much about it in practice. Either way, good luck, and definitely let us know if you find somebody with bigger eyebrows than Rowan Williams. We’ll want to be warned about that right away.

i For Americans used to denominationalism, it’s helpful to understand that the Anglican Communion is made up for the most part of autocephalous churches (provinces) divided by geography. For Anglicans, when these parts work together, it’s ecumenical in the same way that joint contacts or missions between, say, the Russian and Greek Orthodox churches is.

Daniel Schultz, a.k.a. pastordan, is a minister in the United Church of Christ. He serves a small and very patient church in rural Wisconsin. He is the author of Changing the Script: An Authentically Faithful and Authentically Progressive Political Theology for the 21st Century (Ig Press, 2010).