A still from Russian punk group Pussy Riot’s February performance in Christ Our Savior Cathedral, Moscow. Source: unknown.

A review of The Orthodox Church and Russian Politics, by Irina Papkova.

Oxford University Press, 2011.

By Sean Guillory

In late February, four members of the Russian feminist punk group, Pussy Riot, performed a “punk prayer” on the altar of Christ Our Savoir Cathedral, the seat of the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC). Their action, which included singing the song, “Holy Mother, Blessed Virgin Drive Putin out!” targeted the Church’s support of Putin. “The head of the KGB is their main saint / He leads protesters to prison under guard . . . Patriarch [Kirill] believes in Putin / It’s better to believe in God, bitch,” they sang. Pussy Riot’s “punk prayer” has since become an international scandal as three members, Nadezhda Tolokonnikova, Maria Alyokhin, and Ekaterina Samutsevich, are facing a possible seven years in prison for “a premeditated hooligan act based on religious hatred.” Responses from Church officials have been varied. Some, like Archpriest Vsevolod Chaplin, have called for extremism charges to be filed against the group for their “incitement of hatred against Orthodox Christians.” Patriarch Kirill referred to the action as “the Devil laugh[ing] at all of us.” Others within the Church have called for leniency. Archdeacon Andrei Kurayev argued for the women’s exoneration, stating that a severe punishment allows the church to “cling to the shoulder of the government,” undermining the Church’s independence from the Russian state. A petition, allegedly drafted by the Church’s fundamentalist wing, has been circulating in Moscow churches urging General Prosecutor Yuri Chaika to investigate Pussy Riot for extremism. A small protest of Pussy Riot supporters even devolved into fisticuffs with Church supporters outside a Moscow court. The relevance of Pussy Riot’s action goes beyond the legality of profane speech. These multi-vocal responses from inside and outside the ROC speak to contests over its place in Russian society and politics.

Since the collapse of communism in 1991, the Russian Orthodox Church has been searching for its place in post-Soviet society. Was it to revert to a form of caesaropapism, where the church, as before, submits to the whims of the state? Was it to seek symphonia as an equal governing partner with the state? Or was it to remain wholly independent and serve as an actor, albeit a privileged one, within civil society to lobby the state to promote its policies? Given the ROC’s history, there are no easy answers to these questions. The twentieth century was traumatic for Russian Orthodoxy. The communists sought to secularize Russian society by destroying churches, prohibiting worship, and arresting, imprisoning, and executing worshipers and members of the church hierarchy. The last half-century saw the Russian Orthodox Church battered and enfeebled. Despite regaining some traction in Russian society, the traumas of the 20th century linger as the Church seeks to redefine its relationship to the Russian state and politics as a whole.

With this history in mind, those who view the Pussy Riot Affair as exemplary of a fusing of church and state might inject some skepticism into their analytics. As Irina Papkova argues in her book, The Orthodox Church and Russian Politics, the place of ROC within Russian society remains highly ambiguous. Considering the Church’s experiences of repression under communism, many church elites are reticent of becoming too cozy with the state. The state also seems reluctant to share power with the church. Outside of general, and at times, almost formulaic lip-service, few top ranking government officials—from Yeltsin to Putin—have afforded the Church any significant role in state power. The Church and the state may complement each other on many levels, but suggesting political convergence runs afoul of the evidence, Papkova emphasizes. Since 1991, the Church has had few victories in turning Church policy into law. The only significant legislation passed in its favor was the 1997 law that gave the Russian Orthodox Church privileged status—along with Islam, Judaism, Buddhism, Protestantism and Catholicism—as a “traditional” religion of Russia. Even this stopped short of elevating the ROC to a state religion.

An Orthodox priest outside a recently restored monastery in Murom, Russia (Moscow area). Photo by Gerd Lundwig.

While state power remains remote, the ROC does seek to have greater sway over Russian society and since 1991 has openly advocated for its spiritual-political visions to be codified in federal law. Here the Church is more a lobbyist than arbiter of political power, and if its social policy were enacted, it would serve as a quasi-Apostle Peter guarding the moral gates of Russian society. Yet, as Papkova, convincingly shows, the Church and its adherents have seen more defeats than victories. None of its efforts to institute a “Fundamentals of Orthodox Culture” course in public schools or to ban taxpayer identification numbers and “blasphemous” material in media have panned out. Of these initiatives, church teachings in schools remains alive, and the Church has won a small victory as the “Foundations of Religious Culture and Civil Ethics” will be taught to fourth grade students beginning this year. Yet individual schools will still decide the curriculum and parents can opt their children out. Pussy Rioters aside, the ROC’s direct moral and spiritual influence over its flock remains uneven and fragmentary. While eighty percent of Russians identify themselves as “orthodox Christians,” no more than ten percent actively attend church, rendering ambiguous the ROC’s influence on Russian identity. In terms of political influence, Papkova demonstrates, the church is itself internally divided and engages the public using many, often contradictory voices that appeal to distinct and often antagonistic constituencies. Rather than having broad political influence over the Russian polity, the Church’s power remains wholly issue based.

Indeed, the Russian Orthodox Church in Papkova’s book is very much a Church still soul searching. In that search, the ROC appears as a splintered entity, the head of which, the Patriarch, is often incapable of getting its various limbs to conform. Papkova’s Church is one not so much resurgent as schizophrenic, as some of its members advocate democracy and liberalism while others seek to canonize such Russian demons as Ivan the Terrible, the mad monk Grigorii Rasputin, and, in the irony of ironies, Josef Stalin. That the Church functions as an umbrella encompassing many tendencies and political persuasions should hardly be surprising. Yet, as Papkova notes, most scholars treat the ROC as monolithic, anti-modern, caesaropapist, anti-capitalist, and generally incompatible with political pluralism within and without. But religions can and do adjust, however slowly, to present conditions if they want to remain influential, even those as steeped in tradition as the Russian Orthodox Church. The work of Papkova, and a few others before her, in peeling back the layers of the Orthodox onion is a welcomed endeavor.

In studying political plurality within the ROC, Papkova examines the period 1991 to 2008, though the bulk focuses on roughly 1997-2000 to show how various political-spiritual tendencies in the church have tried to influence federal politics. At the center of ROC’s spiritual-political polyglot is the Patriarchate, whose official political visions are codified in the Social Concept. Adopted in 2000, the Social Concept lays out the Church’s position on government, church-state relations, inter-confessional relations, morality and freedom of expression, xenophobia, the West, and the economy. The church’s position on many of these is rather conservative, but not as conservative as one might assume. For example, while it affords itself a penultimate position in regard to Russia’s other “traditional” confessions—Islam, Judaism, Buddhism, Protestantism and Catholicism—it accepts, respects, and even assists them. At the same time, it is virulently opposed to “new” religions—Scientology, new age spiritualism, Mormonism, and Jehovah’s Witnesses and others—and, along with its official religious brethren, sees them as authoritarian, destructive and cultish. Traditionalism may stand at its center, but the Social Contract is a surprising mix of pragmatism, tolerance and acceptance of the modern status quo as it is protective, even aggressively so, of its special status as arbiter of morality in Russia.

Orbiting the Patriarchate and its Social Concept, Papkova identifies three “informal” religious-political tendencies in the church: liberals, traditionalists, and fundamentalists. The smallest group is the liberals, inspired by the late Father Alexander Men (Men was killed by unknown assailants in 1990) and Father Georgii Kochetkov. Liberal Orthodoxy tends to be pro-democracy, politically and spiritually tolerant, sympathetic to the West, and supportive of redistributive capitalism. Orthodox liberals have joined activists in Russia to promote democracy and civil society building throughout the 1990s and 2000s. The second tendency, the traditionalists, favor “Orthodox statism” (provoslavnaia derzhavnost), which calls for a politically active church that will facilitate a “spiritual renaissance” within Russian society. Traditionalists are supportive of monarchy, symphonia, media censorship and state involvment with the economy. They condemn “new religions” and express a veiled anti-Semitism. Traditionalists make up the majority of the church elite and for the most part diverge from the Social Concept in degrees.

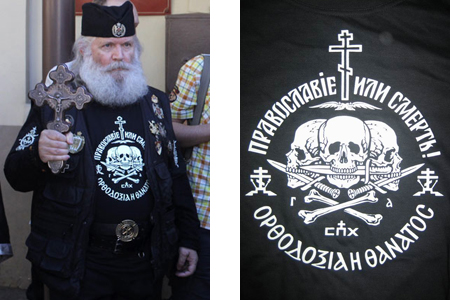

The Union of Orthodox Banner Bearers for a time wore t-shirts emblazoned with the slogan “Orthodoxy or Death,” though a court recently banned the shirts as “extremist.”

The last and by far most interesting tendency is the fundamentalists. Orthodox fundamentalists advocate a return to an imagined pre-revolutionary “Golden Age,” of Church-State relations. Their extreme social conservatism also includes the preaching of apocalyptic visions and Masonic-Judeo conspiracies. The fundamentalists are also the most politically active and publically vocal element of the ROC, and because of this, serve as the protagonists in Papkova’s story. The fundamentalists, through organizations like the Social Committee for the Moral Renaissance of the Fatherland, have sought to defend Russian morality from Satan’s encroachment. Their campaigns against individual taxpayer identification numbers (INN) in 2000, indecent and immoral billboards in 2001, and crusades against artistic blasphemy and sacrilege are laden with millenarian rhetoric and dire warnings of societal rot. The fundamentalists’ fire-and-brimstone approach to politics is what makes them so interesting, and I suspect, why Papkova was drawn to giving them the most attention. A group of believers who pray for acceptance into Ivan the Terrible’s oprichnina to help “throw off the nasty Yiddish yoke” is too good to ignore

Yet, that Orthodox fundamentalism is so colorful is also what makes Papkova’s treatment of them so frustrating. Her examination is formalist, focusing more on their political successes and failures than on what makes paeans to the apocalypse so appealing for an Orthodox believer in post-Soviet Russia. While it is not surprising that the ROC is generally searching for its place in post-Soviet society and politics, the question remains why for some “combating Satanism” is such an integral part of this quest. Here questions of politics moves into questions of belief and faith, both of which take little part in Papkova’s text except as a measurement of Orthodoxy’s place in Russians’ political identity. As she states, “it should be emphasized that all the Komitet’s activism should be understood as political, since for the organization the political survival of the Russian Federation is tied inextricably to its moral spiritual rebirth; neither is possible without the other” (139). True, but the Komitet’s mission is also inextricably rooted in a particular version of Orthodox faith that serves as the idiom for political practice, and the communicability of that idiom requires attention in its own right. Namely, why do Orthodox fundamentalists believe the apocalypse is nigh?

One answer is that the period Papkova examines was one of instability and uncertainty. During such times, fundamentalist rhetoric provides cogent answers. She treats the trauma of the collapse of communism, but not the social reverberations of economic shock therapy, the crash of 1998, the wars in Chechnya, and Islamist terrorism (Moscow metro bombings, apartment bombings in 1999, the 2002 Nord-Ost hostage crisis, and the 2005 Beslan school massacre) on the religious sensibilities of the Russian citizenry. Did Orthodoxy, particularly its more fundamentalist variety, benefit politically from these tragedies? Nor is the politics of Orthodoxy and Putin’s restoration of the Russian state and economy given much attention. Though Papkova’s treatment goes up to 2008, hardly any attention is given to the period 2003 to 2008, the height of Putinism. Short shrift to Putinism is the largest omission in Papkova’s study since by all accounts Putin fundamentally changed Russian politics. One is left wondering how those changes affected Orthodox politics at the official and grassroots levels.

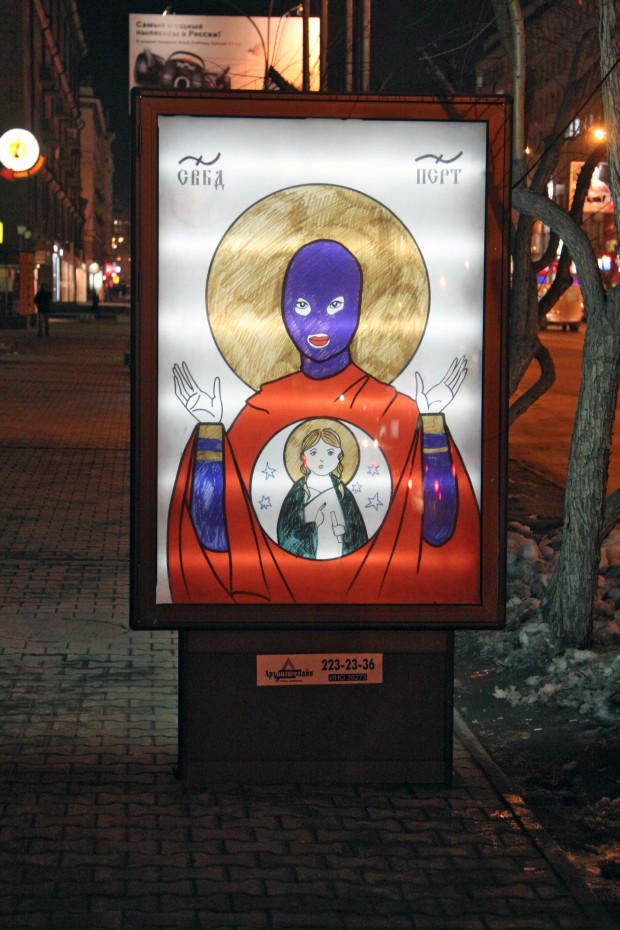

Sign reading “Free Pussy Riot” in Moscow–placing the costumed Pussy Riot figure in the pose of a traditional Marian icon. Source: kissmybabushka.com.

The fate of Pussy Riot remains unknown. Whatever their final sentence, their act and the Church’s multivalent response to it has put issues of church, state, politics and belief at center stage of Russia’s public sphere. Thanks to Irina Papkova’s close attention to Church political ideology and activism since 1991, another interpretation of the Pussy Riot Affair is possible. Rather than viewing the scandal as proof of the ROC having strong ties to the Russian state, perhaps it would be more apropos to see it as yet another expression of a fragmented Church still struggling to assert its place in Russian society. The time is ripe, as the political electricity flowing through the air as called many Russians to ruminate on questions of state, society and politics. Now faith has been added to the mix. And in this sense, four girls in pastel balaclavas singing feminist punk rock and the conservative traditions of Russian Orthodoxy make strange, though complementary, bedfellows.

Sean Guillory is a postdoctoral fellow in the Center for Russian and East European Studies at the University of Pittsburgh. His book manuscript, “We Shall Refashion Life on Earth!” Soviet Youth and the Origins of Stalinism, 1918-1934, examines the often-ignored role the Young Communist League, or Komsomol, played in the rise of authoritarian politics in post-revolutionary Russia. In addition, Sean is an avid “Russia Watcher” and blogs about contemporary Russian politics and society at Sean’s Russia Blog (http://seansrussiablog.org/) and hosts the podcast New Books in Russian and Eurasian Studies (http://newbooksinrussianstudies.com/).

Irina Papkova is Assistant Professor of International Relations and European Studies at Central European University. She received her Ph.D. from the Government Department of Georgetown University and has previously taught at Georgetown and George Washington Universities. Her book, “The Orthodox Church and Russian Politics,” was published by Oxford University Press and Woodrow Wilson Center Press in 2011. She is also a Revealer contributor.