By Alex Thurston

Violence by Boko Haram, a rebel sect in Northern Nigeria that claims to be waging an Islamic jihad against the Nigerian state, has killed over 900 people since 2009, including over 250 in 2012 alone. Domestic and international analysts warn that pervasive insecurity in the country’s Northeast, and periodic strikes by Boko Haram in the capital Abuja and major cities like Kano, are weakening the legitimacy of President Goodluck Jonathan, who like many of his fellow Southern Nigerians is Christian (the North is primarily Muslim). Near-daily commentary speculates that Nigeria is “on the brink” – of civil war, of state failure, or of just plain being a mess. And yet in the South, where much of the country’s economic activity is located, business is going on more or less as usual. Oil is flowing at around two billion barrels per day. Citibank plans to double its investments in Nigeria, to $2 billion, in 2012. Growth, though down slightly from last year’s 7.7%, is projected at 7.2% for the year. The South has its own problems, but the different trajectories of North and South do raise a question about Boko Haram – is the movement just a Northern problem, or is it a national one?

The answer to this question will depend on the movement’s military and organizational capacity, but it will also depend on how the movement’s violence affects existing ethnic, religious, and regional fault lines in Nigeria. These fault lines exist both within the country’s two halves and between them.

Boko Haram and the North: Violence Heads West

Northern and Southern Nigeria, “amalgamated” by British officials into one colony in 1914, have widely different histories. The North, like Nigeria as a whole, has remarkable ethnic, linguistic, and religious diversity – including within Islam. For example, much of present-day Northern Nigeria was ruled in the nineteenth century, prior to colonial rule, by the Sokoto Caliphate, a Muslim empire whose seat was in the far Northwest. But Northeastern Nigeria, the base of Boko Haram today, was under the control of a different Muslim empire, Kanem-Bornu. During the early years of the Sokoto Caliphate, the rulers of these different empires came into conflict militarily and doctrinally, with Sokoto’s leaders criticizing the practice of Islam in Kanem-Bornu and the latter’s rulers refusing to submit to Sokoto’s authority.

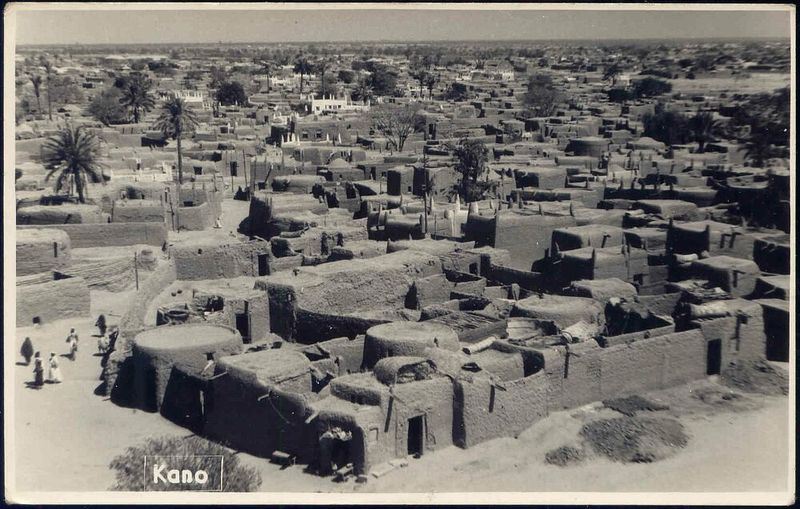

These events inform the present structures of religious and political power in Northern Nigeria. A Sultan still sits in Sokoto, and his lieutenants, the Emirs, have retained their offices in many of the most important territories of the North, such as Kano. A Shehu (sheikh) still sits in Borno. All of these leaders exercise some degree of political and religious influence, but the distribution of power between the North’s regions remains unequal: the Northeast ranks below the Northwest both symbolically (the Shehu of Borno is second to the Sultan of Sokoto in the Supreme Council for Islamic Affairs, established in 1974) and in terms of political power: when the North has produced national politicians, they have primarily come from former territories of the Sokoto Caliphate. Political and historical differences are mirrored by ethnic ones: although the Hausa language is found throughout Northern Nigeria, the people of the Northeast are not ethnically Hausa, but rather Kanuri and other groups.

The North’s internal regional divisions have until recently been reflected in the pattern of Boko Haram’s violence. Boko Haram, which apparently began as a religious study circle and communal living group in the Northeast in the 1990s, first attracted major attention for mass uprisings in the Northeast in 2003-2004 and in 2009. After the resulting security crackdown in 2009 and the death of its leader Muhammad Yusuf in police custody, Boko Haram re-emerged in 2010 as a guerrilla movement. Its assassinations, bombings, and small raids were concentrated in the Northeast, especially in Maiduguri, the region’s largest city.

The Northeast, despite the state of emergency President Jonathan imposed in December 2011, is still the site of weekly attacks. But Boko Haram has projected its violence further afield, carrying out two major bombings in Nigeria’s capital Abuja in summer 2011, a set of coordinated bombings in Kano in January, and a suicide attack in Kaduna this week. This expansion will put the question of Boko Haram’s regional character to the test: if the movement is primarily one of dispossessed, non-Hausa Northeasterners, can it attract the kind of support in Hausa areas that will let it turn a city like Kano into another Maiduguri? The recent bombings and attacks in Kano seem to have received little backing from most residents. The majority of victims have been Muslims, which could indeed provoke a grassroots backlash against Boko Haram. On the other hand, the Northeast is not the only part of the North that is home to frustrated, impoverished youth – the demographic that seems most receptive to Boko Haram’s message.

Boko Haram and the Middle Belt: Violence Heads South

Boko Haram’s expanding zone of violence has also touched areas outside of the “Core North,” including Nigeria’s “Middle Belt,” a region with stunning religious and ethnic diversity, as well as histories of inter-communal violence. Boko Haram’s recent efforts to drive Christians and Southerners out of the Northeast have sent refugees fleeing south. Boko Haram also claimed responsibility for the Christmas Day bombings in the Middle Belt communities of Jos and Madalla, and recently bombed military barracks in the city of Kaduna. Inter-communal tensions in the Middle Belt precede Boko Haram’s emergence, but increased Boko Haram attacks in the region would intersect in ugly ways with these tensions, as well as with the larger national tensions that these conflicts engender.

The most notorious trouble spot in the Middle Belt is the city of Jos. Recurring clashes there over the last decade have pitted primarily Hausa Muslim traders and Fulani Muslim herders against Christians belonging to the Berom and other ethnicities. Violence in Jos sometimes sparks killings in the surrounding villages too. The conflict arises due to struggles over the legal status of non-indigenes, contests over political power, and the manipulation of religious and ethnic identities by political and sectarian leaders. But the complexity of the conflict’s causes is often overshadowed by emotion and sectarianism, with dangerous consequences for inter-communal relations elsewhere in the country. Uduma Kalu, of Nigeria’s Vanguard, writes, “Killings in Jos wear a veil. Sometimes, it has a religious bent. In other times, it is ethnic. But the people know that it is both ethnic and religious and that it can spread to other regions of the country.”

Kaduna, too, is a state filled with tensions. The town of Kafanchan, for example, has seen periodic inter-religious clashes since the 1980s, including in November 2011, while the eponymous capital saw major riots in 2000 and 2002. As in Jos, the violence in Kaduna stems from multiple causes, including the manipulation of ethnic and religious loyalties by politicians. In both areas, government has failed to address core grievances that motivate conflicts and to hold perpetrators of violence accountable; these failures allow cycles of violence to continue.

Other Nigerians care about what happens in the Middle Belt, not least because the heavy immigration in the area means that many have relatives there. Violence in Jos, especially, often makes the national news. Clashes in places like Kaduna and Jos can evoke harsh rhetoric – or even violence – from partisans in other parts of the country. If Boko Haram increases its violence in the Middle Belt, then, the risks of more inter-communal attacks breaking out there will increase, as will tensions across Nigeria. The opaque nature of Boko Haram, moreover, gives cover to other criminals to carry out attacks and robberies, and casts a shadow of mistrust over community relations, as Christians begin to fear that their Muslim neighbors are terrorists, and Muslims fear that angry Christians will mistake them for members of the dreaded sect.

Boko Haram and the South: Fears of Retaliation, Doubts about Government

The North has a reputation for being the poor and underdeveloped half of Nigeria, but figures on Nigeria’s prosperity should not obscure the difficulties Southerners face. The removal of a federal subsidy on petroleum products in January unleashed economic pain on Nigerians across the country, and the ensuing strikes cost the economy as much as $1 billion per day. The strikes are over, but most Southerners, like their Northern counterparts, will still struggle to adjust to the new price of fuel. President Jonathan’s home state of Bayelsa, meanwhile, has offered a reminder in recent weeks that violence is not limited to the North. Bayelsa held a gubernatorial election this past weekend, and the campaign has seen bombings, threats, and an attack on an oil pipeline. The Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) has claimed responsibility for this attack. MEND, a militant group whose attacks substantially disrupted oil production in the Niger Delta, signed an amnesty deal with the Federal Government of Nigeria in 2009. If MEND is back, and the amnesty deal crumbles in the face of militants’ frustration with the government, the Delta will face even more violence, with or without Boko Haram.

Boko Haram’s major attacks, aside from unconfirmed rumors of minor incidents in the South, have so far not extended further south than Abuja, which is technically part of the North. Boko Haram has continually surprised observers with the force and scope of its attacks, but at present the group seems to pose little threat to Southern cities like Lagos and Ibadan, or to oil production in the Delta. The threats Boko Haram poses to the South are more indirect: first, the potential for an escalation of inter-communal tensions and second, the continued erosion of Nigerians’ faith in the central government.

As in the Middle Belt, there are a number of Northern Muslim immigrants in the deep South. For the most part, immigrants live in relative harmony with their Southern neighbors. Many Southerners, particularly among the Yoruba in the Southwest, are Muslim themselves. But the wave of violence in the North has led to an escalation in the rhetoric of some Southern groups who perceive Boko Haram as an anti-Christian movement. Nigerian Christian leaders have mostly emphasized the need for Christian self-defense against Boko Haram, but some go further, warning of retaliation. Militants in the Delta have also threatened to retaliate against Boko Haram, by which they may mean killing Northern immigrants in the South. Attacks on mosques and Islamic schools in January in the Southern communities of Sapele and Benin City suggest that some retaliatory violence has already begun. The longer Boko Haram’s attacks go on, the greater the potential for such vigilante actions.

Inter-communal tensions across Nigeria are fueled by a widespread lack of faith in the central government. Some Nigerians view the military as a force that can impose law and order, as soldiers have periodically done in areas such as Jos. But many Nigerians doubt the effectiveness of other branches of the security forces, such as the police. Above all, many Nigerians doubt the sincerity and the abilities of politicians in Abuja. President Jonathan’s public statement that Boko Haram has infiltrated the government and the security forces adds to doubts about government effectiveness, as some Nigerians already regard the movement as the product of politicians’ patronage for youth gangs. Perceptions that the government cannot, or will not, solve the crisis will encourage some Nigerians, including Southerners, to take matters into their own hands and attack those whom they perceive as a threat.

Boko Haram, then, has triggered a national crisis in Nigeria, but the manifestations of this crisis differ from region to region. What began as a Northeastern problem now threatens to spread to the rest of the North, to fuel inter-communal violence in the Middle Belt, and to touch off retaliatory violence in the South. Oil seems likely to flow, and big-picture economic growth to continue; but in this religiously and ethnically divided country, many eyes will remain fixed, fearfully, on the militants in the Northeast.

Alex Thurston is a Ph.D. candidate in Religious Studies at Northwestern University. For 2011-2012, he is conducting dissertation fieldwork in Northern Nigeria. He blogs at http://sahelblog.wordpress.com.