This week the Obama Administration scrapped the Fairness Doctrine and 83 other media regulations. Kathryn Montalbano examines the ongoing struggle over radio, TV, and now, Internet access and content.

by Kathryn Montalbano

In June Ralph Reed, conservative American political activist and, during the 1990s, executive director of the Christian Coalition, hosted the Faith and Freedom Conference in Washington, DC, perhaps more appropriately referred to as the “Christian Coalition on steroids.” A smattering of Republican luminaries and presidential candidates, including Glenn Beck, Mitt Romney and Ron Paul, were there to woo evangelical leadership and Tea Party activists, providing more proof the two are quite past any ideological differences.

No one better represents this bridge than Reed, as Sarah Posner has noted this summer. Despite a history of scandals that effectively swindled members of the Religious Right, conflating god and anti-government ideology is vintage Reed. He’s asserted that our Founding Fathers “believed that America would succeed or fail based on whether it as a civilization was based on biblical principles” and that Tea Party victories of the 2010 midterms stemmed from an evangelical and Tea Party coalition. The relationship functions, according to Reed, because the former group exhibits “a quintessentially anti-government, corporate-minded ‘Christian’ or ‘biblical’ view of the role of government.”

This alleged anti-government, corporate-minded philosophy hasn’t just helped at the polls. In the fierce debates surrounding Internet regulation and net neutrality—a term coined by former Columbia Law Professor and now member of the Federal Trade Commission’s Office of Policy Planning, Tim Wu—Reed’s reasserting his influence.

Net neutrality, in essence, prevents Internet service providers from creating a tiered price system that would charge clients based on the Internet content or applications they use. In a 2006 Washington Post article, Stanford Law professor and founder of the Center for Internet and Society, Lawrence Lessig, and Robert W. McChesney, professor of communication at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and co-founder of Free Press, a media reform group, compared the detriments of Internet price discrimination to the current landscape of cable TV. “A handful of massive companies would control access and distribution of content, deciding what you get to see and how much it costs,” they write.

Reed has been identified by ThinkProgress (see documents here and another set here) for lobbying in favor of the cable industry’s pricing structure—specifically, for his services to National Cable and Telecom Association (NCTA), a stark opponent of Congress’ and the Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) advocacy for net neutrality. Reed has referred to his contracted services as “‘legal and advertising’ services.” Three million dollars worth of “services,” that is.

According to ThinkProgress’ analysis, Reed markets himself to clients as an influential middleman who can promote their political interests as a vital fulcrum between them and “third party allies.” He’s justified in those claims. While Reed’s been earning his $3 million, his old business partner, Tim Phillips, has directed anti-net neutrality advertising and propaganda campaigns. Phillips, president of Americans for Prosperity (AFP), employed Tea Party and anti-communistic rhetoric in a $1.4 million advertising campaign to defeat net neutrality in 2010. The campaign is misleading for its representation of net neutrality as a government takeover of the Internet.

AFP posits itself as a source of education and mobilization on economic policy. However, its primary anti-net neutrality website, “No Internet Takeover,” provides little if any concrete information regarding the central premise of net neutrality— and nothing on the defining principles of the policy itself. It instead features an inflammatory YouTube video and tautologous, confusing links. One such link is to a statement from the organization’s vice president that essentially reduces net neutrality to unnecessary government regulation. The stipulations of said regulation remain obscure, leaving the terms of “regulation” up to the imagination of the reader.

Of course net neutrality, contrary to the AFP’s projected, propagandistic image of it, has always been the template for Internet infrastructure; neutrality legislation would prevent (rather than cause) censorship and cable companies’ profiteering and discrimination. Net neutrality rules, which the FCC has already set into motion, will prevent censorship of any kind—including that of right-wing, conservative websites.

So why is it, then, that conservative groups like Americans for Prosperity, in tandem with the Religious Right and folks like Reed, are so adamant to stop net neutrality? Though a clear answer may be hard to pin down, part of the answer lies in the fact that these groups want to have their cake and eat it too—to stop the government from “regulating” the Internet while selectively choosing what content is appropriate, i.e. what content coincides with their religious ideology.

Like Reed’s perennial resurfacing, battles for media control continue to come around again. One of the most instructive examples may be the rise and fall of the Fairness Doctrine, a 1949 FCC policy that responded to radio broadcasts of propaganda abroad—in Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy—as well as to racial and religious broadcasts at home–like a 1930s show by Father Coughlin, an anti-Semitic Catholic priest. Evangelicals’ and other religious conservatives’ desire to thwart regulation of the airwaves, even while engaging in their own inter-censorship, defined 20th-century American religious broadcasting. The medium of radio permitted evangelists to re-enter the changing public sphere in a new way and to position themselves as protectors of the nation’s morality against modernism, “communism,” “unnecessary” government regulation, changing family norms, and notoriously, the Fairness Doctrine.

The doctrine set forth two principles: the first stated that programming had to include issues of public interest because, so it stated, limited space for programs necessitated public interest content on the radio (“spectrum scarcity”). The second premise of the doctrine mandated that stations provide a balanced account of issues by giving fair time to both sides.

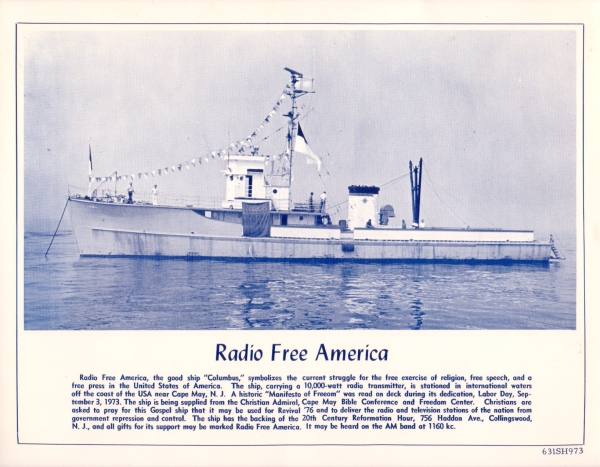

According to Patrick Farabaugh’s Carl McIntire’s Crusade against the Fairness Doctrine: Fundamentalist Preacher and Radio Commentator Challenges Federal Communications Commission and its Fairness Rules, only one radio evangelist was denied a license under the Fairness Doctrine: Carl McIntire. Farabaugh recounts the role McIntire’s vehement opposition to the FCC’s fairness rules played in the ultimate demise of the Fairness Doctrine. McIntire’s 20th-century crusade against radio regulation culminated in his dramatic 1973 protest of WXUR’s failure to renew his show’s license. He took to neutral waters; from the Columbus, a ship twelve miles off the coast of Cape May, New Jersey, McIntire broadcast his infamous pirate station, “Radio Free America,” as retaliation against the license renewal.

But other anti-Fairness Doctrine events in his career contributed to the doctrine’s demise as well. During the week of June 3-7, 1967, only three days after McIntire hosted a “Radio Conference” in Collingswood, New Jersey (which called for the repeal of Section 315 of the 1934 Federal Communications Act, a clause that mandated broadcasters allot equal air time to political candidates running for office), the FCC declared that licensees were now responsible for all programs on their radio or television stations, regardless of their origin of production. This “codification” of the Fairness Doctrine meant to hold station owners accountable for the content they broadcast, thus exerting pressure to better edit programming.

McIntire persisted in his appeal to listeners to pressure the FCC. He was joined by others, including fellow evangelical radio host Billy Hargis. Together they reached more than 500 stations nationwide. By this time, CBS and NBS both supported McIntire’s quest to reverse the fairness rules. The FCC, in its quest to hold corporations accountable, tellingly failed. The corporations and their supporters proved too powerful for government regulation.

Still, a toothless version of the Fairness Doctrine hobbled on. Donald J. Jung argues in The Federal Communications Commission, the Broadcast Industry, and the Fairness Doctrine, 1981-1987 that debate within the FCC from 1981 to 1987 mostly focused on social, economic, and constitutional issues. “The [Fairness] doctrine illustrates nicely the myth of journalistic ethics in the real-world conflict with commercial activity and political advantage,” Jung writes. Opponents of the Fairness Doctrine never forgot religious broadcasters’ support.

Mark Fowler, a former lawyer for radio stations, was appointed as FCC chairman in the 1980s by Ronald Reagan. In keeping with the administration’s pro-business ethos, he sought to eliminate what he and others saw as excessive government intervention, as an impediment to their version of freedom of speech and press. Fowler directly appealed to the National Religious Broadcasters for support. On February 9, 1982, in what sounds hauntingly like a retelling of arguments against net neutrality today, he claimed that “spectrum scarcity” was really a front constructed by an anti-religious FCC to control the airwaves.

As Richard H. Gentry notes in his 1984 essay published in Volume 28:3 of the Journal of Broadcasting, “Broadcast Religion: When Does it Raise Fairness Doctrine Issues,” decades after the doctrine’s initial adoption in 1949, the FCC avoided discussion of what role religion played in issues of fairness. In a 1975 case involving an atheist’s demand for equal response time to an overtly religious program, the FCC chose to tread carefully by claiming it “‘knows of no substantial question in this country concerning the merits of religion and it does not hold that the Fairness Doctrine is applicable to the broadcast of church services, devotions, prayers, religious music or other material of this nature. . . . To the extent that any program, regardless of label, deals with a controversial issue of public importance, the fairness doctrine applies.”

In 1977 a California television program on KVOF-TV/San Francisco opposed equal time for the Council on Religion and the Homosexual after airing a segment that opposed gay rights in the work force and in housing. KVOF’s argument against accepting the Council on Religion and the Homosexual’s fairness challenge was simply a question of rhetorical framing. Responding to vocal anti-gay rights activist and former actress, Anita Bryant, the station stated, “Despite the clear political implications of her rhetoric, Ms. Bryant expressed herself in religious terms. While all religious discussions find both source and effect in the political and social spheres of influence, once these discussions are couched in Biblical and religious terms and issued from a primarily religious forum, they constitute religious views’ which should not be regulated by civil tribunals.”

Thus KVOF essentially claimed that, with the FCC’s backing, “religious issues” should be granted autonomy from the legal principles, sanctions, and laws guiding radio broadcast in the public sphere, a claim based simply on the categorization of “biblical or religious” language as benign and outside the spectrum of controversy, despite (in)accuracy, contextualization or the political impetus of its content.

Deliberation surrounding the Fairness Doctrine’s demise demonstrates the shifting and often conflicting concepts central to these ongoing debates about media fairness. “Public” and “fair” have naturally been framed and reframed over the decades, blurring any divide between politics and religion. Shifting “ownership” of and “responsibility” for the media landscape ultimately permitted the slippage of the Religious Right into the political body of the “majority”—thanks to a continuing alliance with like-minded corporate interests. This gradual consolidation of media bandwidth allowed politically motivated religious groups to freely project religious views without sanction. To much of the public, the repeal of the Fairness Doctrine meant preservation of free speech. No longer were religious groups targeted with law suits or accusations of imbalance. Less publicized was the complex alliance of corporate power and deregulation policy within and between the government and religious broadcasters, an alliance which ultimately developed into the current (relatively) uncensored and undoubtedly polemical American broadcasting system.

Julie Ingersoll has reported that statements by David Barton, a PFAW radio show host and self-styled historian to the Religious Right, (including a few Republican presidential candidates) qualify net neutrality as ‘Unbiblical Socialism.’” Ingersoll writes that “FCC-supported net neutrality legislation which, as PFAW put it, ‘ensures that Internet service providers can’t charge higher rates for faster delivery of content,’ violates biblical principles of free market, and that they are ‘socialist.’”

Socialism, according to Barton, is “any move away from what he sees as an unfettered free market, any regulation or involvement on the part of government. . . and of course he thinks that private ownership and free markets are biblically sanctioned,” writes Ingersoll.

But the inconsistency is evident. Republicans, religious conservatives, and Tea Party members have not worked to keep the Internet totally free, but merely free game for corporations. Barton has stated, “‘This is not anarchy. We’re not suggesting moral license, we don’t want to have obscenity, pornography, child pornography …that’s not it. You still have moral laws to follow. We just don’t want micro managing by the federal government.’” Nonetheless, the Internet is the best place to go for obscenity, pornography, child pornography and such. In Barton’s world, either incoming, censoring corporations will clean up the Internet’s act or the seedier stuff on the net can’t compare to limiting the capitalistic rights of the captains of media.

Moral hierarchies aside, the marriage between political, corporate and moral constituents carries on, with hoodwinked consumers blessing their lucrative alliances. At the National Religious Broadcasters Convention last February—an event that drew, among others, such conservative activists and broadcasters as James Dobson, whose “Family Talk with Dr. James Dobson” radio show is carried by 300 stations—House Speaker John Boehner made it quite clear what he considered the media’s role to be. Within his overarching tirade against the national debt, taxes, and encroaching regulation, he asked that religious broadcasters speak about the national debt on their programs in the same way they do about family values. Boehner also encouraged broadcasters to stand up for freedom, a “God-given right” that was being attacked by the FCC via net neutrality just as it had been by the Fairness Doctrine.

Yet there is no complete consensus between anti-net neutrality conservative groups (with which evangelicals predominantly associate) and the diverging, relatively supportive stance on net neutrality articulated by the Christian Coalition and other such larger institutions—institutions which more readily separate economic issues from concerns about content. But as Ralph Reed well knows (and as history of the Fairness Doctrine shows), the “public” is quite often willing to be told what to do.

Kathryn Montalbano is a Ph.D. candidate in Communications at Columbia University, studying the triangulation of religion, politics and media. She has been an intern at The Revealer this summer.