Part of The Revealer’s series on the John Jay report, “The Causes and Context of Sexual Abuse of Minors by Catholic Priests in the United States, 1950-2010.”

by Peter Bebergal

The Sixties counterculture beleaguered most traditional religious communities. Not only was there an increase in behavior deemed inappropriate (drug use, promiscuous sex, and the generalized spread of anti-establishment ideas), there was what came to be seen as a distracting interest in non-Western, non-traditional spiritual philosophy and practices. Compounding this was the insistence by many young people that psychedelic drugs were a profound catalyst for helping them to break free of what they saw as dusty and dried out teachings spouted by clergy who had no understanding of the injustices of a country torn apart by war, racism, sexism, and homophobia.

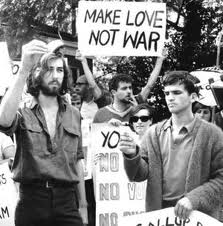

It’s no surprise then that the recent report on the “causes and context” of sex abuse in the Catholic Church claims that one factor was the prevalence of counterculture values that peaked in the mid- to late-Sixties, characterized in the popular consciousness of hirsute young people taking drugs, having sex, and otherwise dropping out of society in pursuit of a naive belief in a cosmic utopia. This stereotype would ultimately reduce the Sixties counterculture, an extremely complex and diverse movement, to a kind of youthful pathology, or simply, deviance. As the report says: “The rise in abuse cases in the 1960s and 1970s was influenced by social factors in American society generally. This increase in abusive behavior is consistent with the rise in other types of ‘deviant’ behavior, such as drug use and crime, as well as changes in social behavior, such as an increase in premarital sexual behavior and divorce.”

While the authors may not have intended it, they perpetuate a subtle yet pervasive idea that the American counterculture–which included anti-war activists, artists, musicians, psychologists, civil rights workers, and yes, dirty stoned hippies–as a whole was deviant, a deviance grossly manifested in the sexual revolution.

At the time it was difficult for the mainstream to grasp what was really going on. Youth weren’t just taking road trips and smoking some reefer. They were part of an enormous cultural shift that felt like an attack on everything that America had built after the Second World War, when a generation of men came home on the GI BIll to rebuild the country out of surplus steel. Hard work won the war and remade the country so that it appeared the Depression had never happened. Young people growing their hair, asking questions about the government and its policies, and protesting the Vietnam War were worse than disrespectful; they were kicking the iron balls of the men who had lost their lives to protect what we have.

This generalized, often unconscious, resentment of the Sixties counterculture made it easy to stereotype, and the often outlandish behaviour of hippies made them an easy target for the media. A 1967 New York Times article described them like this: “Hippies like LSD, marijuana, nude parties, sex, drawing on walls and sidewalks, not paying their rent, making noise, and rock ‘n’ roll music.” Behind all this caricature was women’s liberation, the civil rights and anti-war movements, and even a powerful spiritual revolution, things much more threatening than “drawing on walls,” but things much more difficult to make easy fun of.

By infantalizing hippies, the culture–and by extension the media–infantalized the urgency behind the demonstrations, the art, the music, and yes, the sex. The current media focus on the section of the report that suggests sex abuse by Catholic priests was partly a result of “a new ‘valuation’ of the individual person [which] fostered the exploration and pursuit of individual happiness and satisfaction” simply indicates that they (and we) too have not gotten past gross simplifications of the Sixties as nothing more than a period of sex- and drug-fueled hedonism.

Despite this being only a small section of the actual report (and despite the report’s production by a source outside the church, albeit church financed) it’s one loaded with remarkable inight into the way the Church views not only the Sixties, but the notion of the “individual person.” The logic goes something like this: Child sexual abuse by priests is an “individual act,” not one that includes the priest’s identity as part of the larger institution. Divorce is also something that unravels a person from the Church and its teachings. Therefore, the rise of divorce, presumably a result of “the reemergence of a feminist movement” and an emphasis on personal choice, created a cultural milieu where sexually abusing children was normalized.

This absurd conclusion reduces the sexual revolution, a very complex configuration of women’s lib, gay rights, and an earnest attempt to lose the shame around sex that had become woven into the fabric of relationships, to what it calls “behavior”–specifically divorce and homosexuality, also very complex things that are not reducible to simple categories. Having reduced the revolution to these “deviances” in the first place, the report pathologizes divorce, homosexuality, and by extension, the entire sexual revolution by suggesting that homosexuality and divorce are ungodly seeds from which the sexual abuse of children by priests sprouted.

Because divorce and homosexuality are the bogeymen of the Church, they serve as the two most representative, lived examples of what is most at stake for the Church’s authority: Both are acts of individuals living that go directly against church teachings and explicitly defy church law. Absurd claims by the religious right that the legalization of gay marriage will prompt the normalization of acts like bestiality are not unlike this report’s equation of molestation of children with the sexual revolution.

Among other things, the Sixties put ownership of pleasure into the hand’s of individuals, which for women’s liberation activists also meant claiming their sexual bodies as their own property, not objects that could be dictated by conventions or hierarchies. It’s distressing, to say the least, that society’s effort to remove power over sex from the Church’s purview could be seen by the church as society’s tacit approval of exploitation of children. Sexual abuse is not merely an item on the human sexual behavior menu that one chooses without consequence, like oral sex or the missionary position.

The report concludes that one factor of the abuse was “the influence of the overall pattern of social change” (i.e. the sexual revolution), an absurd, but not atypical inference. The Sixties and Seventies represented a time of unprecedented social tumult in America. The turbulence was a result of a wave of factors, but it hinged on a public and vehement opposition to racial segregation, war-mongering, cultural and religious homogeneity, and inequality between the sexes. Priests like everyone else, were often responding to an anxious and restless climate by acting out on previously subsumed mental illnesses.

As Tom Wolfe once remarked about the use of LSD at the time, the drug didn’t make you crazy, but if you had any proclivity for insanity, acid would amplify it. The Sixties and Seventies were a giant cultural amplifier, exaggerating every personality type, opening the doors of both perception and pathologies. No one was immune, not even those protected by the high walls of the Church. Nevertheless, instead of taking a macro view of the era, where an entire country was rocking and reeling like a dingy in a storm, the report chooses a microscopic view where the only thing going on was divorce, homosexuality, and crime. This is just another example of the Church’s inability to see how it exists in a context larger than it’s own concerns and fears; that it’s teachings will be undermined by the threats of regular people responding to their lived lives outside the norms of the Church.

Peter Bebergal is author of Too Much to Dream: A Psychedelic Boyhood, a memoir/cultural history of drugs and mysticism (Soft Skull Press, 2011) and co-author, with Scott Korb, of The Faith Between Us (Bloomsbury, 2007). He blogs at mysterytheater.blogspot.com.

This article is part of The Revealer’s series on the John Jay report, “The Causes and Context of Sexual Abuse of Minors by Catholic Priests in the United States, 1950-2010.” Read additional commentary by Frances Kissling, Elizabeth Castelli, Amanda Marcotte, Scott Korb, Mary Valle and others here.