by Ari Stillman

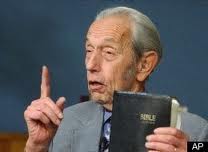

Christianity has mastered the art of being wrong. After all, it began as a reaction to the unfulfilled Jewish prophecy of the coming of the messiah. Its various traditions and uproots are rife with prophecies that have failed to come true. Given this 2000-year history of failed predictions, Christian leaders and theologians have gotten quite skilled at the art of re-interpretation or surviving the great let-down. Failed predictions like yesterday’s by Harold Camping, the California evangelical preacher who selected May 21st for the Rapture after a flawed prediction in 1994, are part of this lively tradition, a tradition that may give us clues as to what we can expect from Camping’s camp after faux doomsday.

As history has demonstrated, interpretation of biblical prophecy is common — and so far inaccurate when it comes to dates. While Jews measured Jesus up against their criteria for the messiah and claimed, “That’s not our guy,” Christians have perfected the art of predicting His precise plans. (If you’ve ever wondered about Jewish neuroticism, ask one how long they’ve been waiting.)

Harold Camping’s prophecy that God would gather up his believers yesterday — at 6 p.m. everywhere because God apparently believes in time zones — is not particularly unique. While it would be fun and all too easy to poke holes in Camping’s methodology, a far more interesting and relevant question is what will happen to Camping and his followers now that his prediction has failed to manifest? Camping’s prediction was that all true believers would be taken up by the Lord and that the rest of mankind would be left to experience hell on earth. But only until October 21, 2011, when God would destroy all of creation.

What will Camping and his followers believe since they haven’t been raptured as they had hoped? Will they still believe that those who were worthy were taken up (even if everyone is accounted for) or will they lose faith in the movement? As one of them said in an interview with NPR, “If I’m here on May 22, and I wake up, I’m going to be in hell.” If you think the ridicule on earth is bad, just imagine the ridicule in heaven for those believers-proven-wrong!

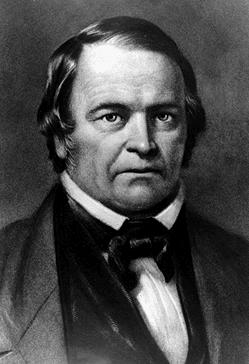

Historically when a prophecy has failed to come true, believers have rationalized the error, often attributing it to bad math. A parallel case happened with the Millerites, a Baptist group headed by William Miller, a layman and amateur bible scholar, who predicted that Christ would bring rapture in 1843. When the original date came and went, Miller asserted that the Second Coming would actually occur in the Jewish calendar year rather than the Christian one, a correction that bought them an extra year. When that date passed another date was offered, October 22nd, the “true midnight cry,” which too came and passed.

This final disconfirmation, known as the “Great Disappointment,”‘ ended Millerism as it existed. Some followers voiced belief in the expectant but temporally unspecified Second Coming. Others who believed Jesus had come spiritually but not literally on October 22 became known as Spiritualizers. Still others who believed that something concrete but misinterpreted had occurred eventually congealed their notions and formed the Seventh-day Adventist Church which today has millions of followers all over the world.

In his classic 1956 book, When Prophecy Fails, psychologist Leon Festinger offers a compelling explanation for why believers tend to experience a renewal of zeal rather than disillusionment when predictions turn out false. Believers look to each other to affirm any rationalization or amendment of the prophecy so that it seems validated. The more people who affirm the rationalization, the more credence is given to it. For those who are isolated from fellow believers, without such affirming company, they tend to defect the cause. However, looking to each other for support is not enough, as believers still know that their prediction was false and their preparations wasted, so some dissonance remains. To combat this, one obvious course of action is to proselytize — a path the Apostles adopted when Christianity was widely regarded by the Roman Empire as a deviant cult. And so was demonstrated the persuasive power of the perceived majority. The world is flat. The sun revolves around the earth. The end is coming…. In this way, failed predictions can work kind of like a gateway drug for followers. (Except with, say, marijuana, you can be raptured whenever you want; far more effective than waiting.)

So where does all this disappointment (and precedent) leave Camping’s raptureless followers? Perhaps they will redouble their efforts and continue to herald doomsday on May 21st next year, much as the Millerites did in 1844. Perhaps Camping will concede that he made an error somewhere in his calculations and will consult the Bible yet again for answers — and eventually announce a new date. Or, perhaps he will adhere to his beliefs, assume that none of humanity was righteous enough to get raptured, and continue heralding doomsday. Even if not accurate, Camping is righteous.

Despite the bible’s patent contradictions, it is clear in conveying that no man can know when the end will come. Human predictions on the matter are by default destined to fail. This doesn’t stop many from trying however, much to the sensational amusement of the rest of the world. Yet, despite all the failed predictions throughout recorded history, new predictions keep arising. It’s a powerful testament to the nature of faith — faith in the face of doubt, self-sacrifice, disappointment and disillusionment — that Millers followers carried on. Perhaps Camping’s followers will do the same, because of — or in spite of — human error.

Ari Stillman is a graduate student at Vanderbilt University studying sociology of religion. His research interests include disparity between belief and practice, religion in a post-religious age, and how cultural phenomena came to be. He blogs regularly about the degeneration of American culture at www.symptomsofamericana.blogspot.com.