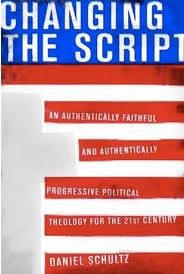

Changing the Script: An Authentically Faithful and Authentically Progressive Political Theology for the 21st Century, by Daniel Schultz. Ig Publishing (2010) $15.95

Reviewed by Brent A. R. Hege

For as long as there has been a religious right barging its way into Americans’ lives, bedrooms, pocketbooks and polling places, there have been religious progressives wondering how perceptions of their faith had been hijacked and twisted into something virtually unrecognizable. The record of the religious right is as long as it is upsetting: from creationism in public schools ( the Scopes “Monkey” Trial of 1925 to the Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District case of 2005) to Judge Roy Moore and efforts to eliminate the wall between church and state; from the Terri Schiavo fiasco to Proposition 8, the tendrils of Christian conservatism have reached into virtually every corner of American life. Many critics ask, often with exasperation and even resignation, where is the religious left? Where is the alternative vision, the principled opposition, the united voice of a sane and progressive religious movement raised in righteous protest?

Yet the voice of the religious left is present; in the church, in the academy, and in the public square. However, the complications of publicly identifying as a Christian cuts to the heart of the many problems facing the religious left in the United States and often keeps our voices from being heard or credited. “Christian” often equals “conservative” in the public mind, as the mainstream media typically consult a white, male, evangelical Christian or conservative Roman Catholic for the “Christian” perspective on the issues of the day. For progressive Christians, this is a triply lamentable situation. On the one hand, they must resist such a facile identification of Christianity with Republican policy and a conservative worldview. But on the other, progressive Christians must often confront those within the progressive movement who are equally likely to paint all of Christianity with a broad brush as inherently incompatible with a progressive agenda. Finally, progressive Christianity is unlikely to garner the same amount of media attention in today’s marketplace because thoughtful and nuanced articulations of tolerance, love and mercy from a progressive Christian simply do not win the same ratings as a frothing rant against “the gays” or “the immigrants” or “the terrorists” by a spokesman of the religious right who can barely contain his excitement that someone else might soon be instructed (or marginalized) in the name of a star-spangled, banner-waving Jesus.

This marginalization has only become more grave as we head into an election year dominated by Tea Party candidates hell-bent on unraveling decades of progress in areas of civil rights, economic policy, environmental regulation, and science literacy. One need only read the statements of Christine O’Donnell, a Tea Party darling and U.S. Senate candidate from Delaware, to recognize the perils of a conservative Christian political resurgence.

And yet. For those who arrive at their progressive convictions from their religious convictions, all hope is not lost. There is within Christianity, as there is within all of the world’s great religious traditions, a long and noble history of justice, mercy, and a vision of a better world. Religious progressives tap into those histories to fund their articulation of a more just society, yet the message often fails to reach beyond the walls of the church and the academy to enter the public consciousness. Where is the vision to move beyond the old stalemate of us vs. them, of the “real America” vs. everyone else, of rich vs. poor, of white vs., well, everyone else?

Daniel Schultz, a pastor of the United Church of Christ and founder (as “pastordan”) of the progressive faith and politics blog Street Prophets, has added his voice to this chorus with Changing the Script, a template for a fundamental rewriting of the narratives we currently live and endure. He points a way forward for religious progressives yearning for a new order by tapping into that long and noble history of prophetic examination and Christian hope. Taking his cue from Old Testament theologian Walter Brueggemann’s critique of an American narrative of “therapeutic, technological, consumerist militarism,” Schultz suggests that just such a fundamental shift of narratives, a “change of scripts,” is required to pull America back from the brink of economic, social and psychological collapse and to direct us toward a new, more just future where the dignity of every person is valued, where American power is expressed through mutuality and cooperation rather than force, and where inequality, not difference, is the scourge to be defeated.

Combining insights from biblical scholarship, theology, ethics, sociology and politics, Schultz presents what he calls “an authentically faithful and authentically progressive political theology for the 21st century” that raises three issues representative of the sickness of an American culture too long dependent on a conservative Christian worldview: the abortion debate; the current economic crisis – nicknamed “Big Shitpile” – and the consumerism that fueled it; and American militarism, specifically the use of torture. With these three issues as points of departure, Schultz calls into question the dominant narratives of therapeutic hubris (that there is a procedure or treatment for every ill that will eliminate any trace of pain or inconvenience from our lives), technological hubris (that human ingenuity will ultimately solve every problem), consumerism (that human beings are and ought to be defined by their purchasing power and material possessions), and militarism (that violence and war are laudable pursuits rather than tragic failures). Woven into the fabric of Schultz’s critique is a respect for the prophetic tradition of the Old Testament, the countercultural, indeed radical, teaching and ministry of Jesus, the political realism and “pessimistic optimism” of American political theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, and the progressive vision of liberty and justice for all, not just for those who pass muster as “real Americans.”

The use of “narratives” to address the problems facing American society at the dawn of the 21st century and to suggest a progressive vision to correct those problems reveals the scope of Schultz’s vision in Changing the Script. The problem, as he understands it, is not merely one of policy or individual motives or the trajectory of current events. Rather, the problem lies in the narratives we inherit and continue to tell ourselves in order to make sense of the world and navigate our way through it; the scripts we follow when living our lives. History does not unfold blindly, nor does it stretch bare before us for interpretation. We understand the world and the events of our lives always with the aid of a certain narrative, a comprehensive framework from which we draw meaning and value. We follow scripts prepared for us, often unknowingly, that instruct us on how our lives should unfold and we chart our paths forward with their aid, often, understood as “the way things are.” We inherit them from our culture, from our history, from politicians, media and corporate advertising, and, yes, from our religious traditions. But there is nothing inevitable or obvious about these narratives; nor is there any reason why they cannot (and, Schultz argues, must) be changed if we are to chart a new course for our national life. From Brueggemann, then, Schultz borrows this theme of narratives to unravel the stories we tell ourselves and to reveal what we have long suspected, that our unexamined scripts are corrupting the “soul” of the nation and leading us into an unsustainable, perilous future.

What Schultz presents in this book is not a systematic description of American political life, nor is it a professional work of academic theology, biblical scholarship, or ethics. It is, true to his style, a work that blurs the line between church and society, between academy and populace, between religious and secular progressives (this is, I suspect, precisely what he means by subtitling his book “an authentically faithful and authentically progressive political theology for the 21st century). The vision of the “big tent” drives the style and the arguments Schultz makes, preferring coalition-building to the further entrenching of divisions, common ground to a siege mentality. What Schultz is after here is not the impossible dream of a sudden end to the divisions between Right and Left. Rather, he insists that among progressives (both religious and secular), there is so much more that unites us than divides us. He urges progressives of all stripes to recognize this fundamental unity of vision while respecting the multiple sources that fund it.

Progressive Christians will feel at home in Schultz’s references to biblical texts and Christian symbols, while secular progressives will hear familiar themes of economic and social justice and discover common goals, such as civil rights, fair economic policy, environmental stewardship, and an end to American imperialism. Indeed, one of the book’s great strengths is Schultz’s constant reminder that secular and religious progressives share so much more in common than the religious foundations that might divide us. At the same time, however, Schultz doggedly insists that in order to be a progressive one need not, indeed one must not, surrender the narratives and the worldview that make one a progressive in the first place, whether the source is religion, philosophy, personal experience, or simply a passionate sense for the way things ought to be. For progressive Christians, this means seeking allies wherever they might be found in the broader progressive movement while reclaiming and celebrating the specifically Christian roots of their progressive ideals; for secular progressives it means recognizing and celebrating goals and dreams shared with Christian progressives even when they are funded by unshared religious sensibilities.

Schultz reminds us that it is in striving that we find hope and it is in solidarity that we find strength.

Dr. Brent Hege is a Lecturer in the Department of Philosophy and Religion at Butler University in Indianapolis and has contributed to Religion Dispatches, Talk To Action, and Street Prophets

Thanks for writing, Colin. Perhaps the definition of Christian, however, doesn’t belong to you or to priests or any one church, but to that person who says, “I’m a Christian because this is what I believe….”