by Becky Garrison

Look for the words social justice or economic justice on your church website. If you find it, run as fast as you can. –Glenn Beck, March 2, 2010

Since Beck uttered this and related comments on his radio show, much ink has been spilled decrying his analysis of one of the basic tenets of Christian teaching. While The Catholic League came to Beck’s defense, “progressives” like Sojourners founder Jim Wallis suggested that viewers and advertisers instead leave Beck, though they later gave Beck some PR attention by placing him on the cover of Sojourners (September 2010). Other progressive groups like Faithful America continue to mount campaigns against Beck’s rantings in the hopes such advocacy efforts will result in strategically placed media and will increase both the nonprofit’s political profile and donor base.

But the battle to defame “social justice” is as old as the New Testament itself, a point made by Fr. James Martin, author of The Jesuit’s Guide to Almost Everything, on the Colbert Report last March. Martin describes how throughout the gospels, ”Jesus choose to be poor not only to show us what it means to live simply but also to show God’s love for the poor.”

Since the advent of radio, popular yet polarizing figures like Father Charles Coughlin, who first supported President Franklin Roosevelt then became a strong opponent of the president’s social services agenda, have used their extended reach to spew forth rhetoric that bears no resemblance to the Beatitudes (see Matthew 5: 7). In the 1970s, a group of evangelical and fundamentalist Christians brought the Religious Right to power when they joined forces over a battle for private, federally funded Christian schools to practice federally outlawed segregation.

Through grassroots organizing efforts, these leaders later aligned with “pro-life” Catholics, who employed “family values” rhetoric to denounce government funding for social service programs. In the process they demonized fellow evangelical Jimmy Carter while helping to usher in Reaganism and an era of social service cuts that kept in place punishing class structures while starving government of it’s ability to promote financial equality.

(Those wishing to further examine the historical connection between fundamentalism and capitalism might want to start by reading The Family: The Secret Fundamentalism at the Heart of American Power by journalist and founder of this site, Jeff Sharlet.)

Even though most Religious Right icons have faded into the sunset over the past decade, this movement remains embedded at the local level, thanks to enduring grassroots organizing (funded by corporate and think tank organizations invested in their social agenda); a legacy established in the 1990s by The Christian Coalition and other religious right groups. The current global financial crisis, coupled with continued acts of terrorism, has created a cultural anxiety that “Christian” organizations like the American Family Association use to their full advantage. Thanks to conservative talk radio and Fox News, figureheads like Glenn Beck, Sarah Palin, and Ann Coulter can be manufactured to spearhead so-called populist movements like the Tea Party that unify both fiscal and religious conservatives. (For the latest updates regarding mergers that employ the rhetoric of religious freedom to justify capitalistic ventures serving a corporate ideology, see Sarah Posner’s reporting at Religion Dispatches.)

In lieu of a reasoned debate critiquing the efficacy of specific programs, these celebrities have become accustomed to mounting a media circus that would put P.T. Barnum to shame. Over at Salon, Micheal Lind recently proclaimed, “The counterculture is back. Only this time it’s on the right.” Thanks to the power and global reach of electronic media, these performance artists have masterfully crafted a conservative narrative, a brand of Americana that only exists in TV Land circa the 1950s. As Posner observes, Beck’s religious historical trek into la-la-land ”resembles what would result if and Billy James Hargis and Joseph McCarthy collaborated on a picture book for preschoolers on the history of the soup kitchen.”

Self-appointed ringmasters such as Beck, inheritors of a 40 year — and longer — project to erode meaningful social policy, have gained considerable notoriety by erasing social justice history, perversely claiming the Martin Luther King mantra of civil rights and proclaiming that the phrase “social justice” cannot be found anywhere in the Bible. (Beck, a Mormon, conveniently avoids references to the Book of Mormon. Perhaps he’s aware of Philip Barlow, the Arrington professor of Mormon history and culture at Utah State University, who’s said “one way to read the Book of Mormon is that it’s a vast tract on social justice.”) While Beck’s total number of viewers is down nearly 30 percent since the start of 2010, dropping from 2.9 million to 2.1 million, and despite ongoing critiques of Beck’s message and methods, he still remains number one at his time slot.

The Revealer spoke to several commentators to find out why “social justice” continues to be portrayed as a dirty term. Daniel Schultz, a pastor and author of Changing the Script: An Authentically Faithful and Authentically Progressive Political Theology for the 21st Century, stated in an email that the quest for fame and fortune appears to be at the root of this social justice debate, at least for Beck:

Social justice has become a dirty word in ‘polite’ circles because some schmuck named Glenn Beck spent a lot of time and money making it so. Where I’m from, among the mainline Protestant churches, social justice remains at the heart of Christian ministry. We do not intend to allow partisan hacks like Beck to take away our faith for the sake of ratings.

In an email interview, Serene Jones, President of Union Theological Seminary in New York City, challenged Beck’s assertion that social justice is not biblical:

It is true that we don’t find the words “social justice” in the bible. But in both the Hebrew scriptures and the New Testament we find the concept of “righteousness,” which is literally translated and understood as “justice.” God is just, God is righteous, God calls us to be righteous – as in right, just relation. There is also the concept of shalom in the Hebrew scriptures which is distinctly related to the social order – shalom is an idea of perfect social, communal peace. It is very clear in scriptures that if the social order is marked by shalom, then the distribution of wealth is equal. It is true that Protestant reformers urged us to avoid works of righteousness. They were concerned that we would think there was nothing we could do to earn God’s love which is really given unconditionally, by grace. But they were quite clear that we were still called to live righteous lives, which means lives of social, public justice, not just private morality. In the Hebrew scriptures and the Jewish community from which they came, this idea is distinctly state justice – not private or individual. In fact, it is hard to imagine a statement more antithetical to both the Hebrew bible or the New Testament than “there is no mention of social justice in the bible.” Social justice is simply describing love with legs. And love, as we all know, is the greatest commandment of all.

(Union Theological Seminary faculty and students have weighed in with their analysis of this term and its origins, a dialogue that was triggered by Glenn Beck’s attack on James Cone, the Charles A. Briggs Distinguished Professor of Systematic Theology at UTS.)

Fr. James Martin gives this explanation of social justice via an email exchange:

For the Christian, social justice should be at the heart of his or her life of discipleship. When Jesus talks about what’s necessary for entrance into heaven, he doesn’t talk about how we pray or what church we go to. He’s pretty blunt: he says it depends on how you treat the poor. (Matthew 25) And the movement for social justice attacks the root causes of poverty, the structures that keep people poor. But somehow working for social justice, which has been an explicit part of the Catholic tradition for over 100 years, is now seen as “communist” or “socialist.” In these situations I like to remember the comment of Dom Helder Camara, the Catholic archbishop of Recife, and a great apostle of the poor: “When I feed the poor, they call me a saint. When I ask why they are poor, they call me a communist.”

Some people who aren’t interested in addressing what keeps people poor — whether out of ignorance of these factors, a fear of engaging these issues head on, or even an unconscious contempt for the poor — have conveniently labeled social justice as “communist” or “socialist.” This effectively demonizes those who work for social justice. It also removes one’s responsibility to address the structures that keep people poor. And of course the elite are threatened by the notion that they live in a society (as we all do) in which some social structures engender poverty. And yes, I think the media is partly responsible for this. Glenn Beck’s repeated tirades against social justice probably reached more people than hundreds of homilies and sermons by good Christian preachers who are devoted to carrying out Jesus’s message to care for the poor. Frankly, when people talk about Christian values, I wonder why they’re not talking more about social justice.

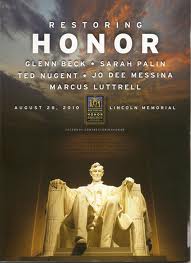

The crowd attending Glenn Beck's "Restoring Honor" rally in Washington DC, Saturday, Aug. 28, 2010. (AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin)

In print, many others have addressed the legacy of anti-social justice talk and Beck’s place within it. Peter Laarman, Executive Director of Progressive Christians Uniting, offers this cautionary note in a recent article, regarding those progressives who critique Beck’s biblical analysis without getting to the root of the problem:

The “Beck is wrong on the Bible” stuff is all good as far as it goes, and I’m glad to see it. But it does not address the larger and largely undiscussed problem of where Christians of all flavors stand on the key question of who is responsible for maintaining a modicum of social equity.

Sarah Posner describes how those who align themselves with what she calls the “libertarian-Tea Party-Christian-worldview-ahistorical-revisionist wing of American politics,” share the anti-government sentiments espoused by Beck & Company, a point often overlooked by religious progressives in their quest to denounce Beck:

Religious liberals who protest Beck’s theological heresies would do well to recognize the dangers of his other heresies as well. It’s not enough to defend the Bible from Glenn Beck; liberals will also need to defend the role of government in creating a social safety net and a regulatory structure that protects and enhances the economic lives of its citizens. While Beck has his conservative critics, they do agree on one thing: government is evil. Unless religious liberals defend the role of government, they provide an opening for Beck and his crew to redefine social justice to mean conservative Christianity is our government by proxy.

During a key mid-term election season, will liberals be willing to advocate for a governmental safety net knowing that pushing for increases in government spending will almost undoubtedly have repercussions at the ballot box? Conversely, how will Republicans respond to this vocal counterculture that threatens to move the party to the extreme right? Despite all the rhetoric, the cold reality remains that no institution — religious or otherwise — has the resources required to adequately address the massive needs brought about by the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression.

So, who exactly will provide for the least of these? The fact that conservatives like Glenn Beck have failed to propose an alternative solution to big government’s correction of economic injustice speaks loudly to their real agenda. This is something that the left has yet failed to clearly and meaningfully point out. Or, as Laarman asks of liberal and moderate Christians, “Do you care enough about the poor and vulnerable to declare yourself an unabashed Big Government supporter? Because equivocation on this one equals suffering and death.”

Becky Garrison’s books include Jesus Died for This? A Satirist’s Search for the Risen Christ (Zondervan, August 2010) and Starting from Zero with $0: Building Mission-Shaped Ministries on a Shoestring (Seabury Books, September 2010).

Read Becky Garrison’s satirical post on SNL’s inability to top Glenn Beck’s “Restoring Honor” rally here.