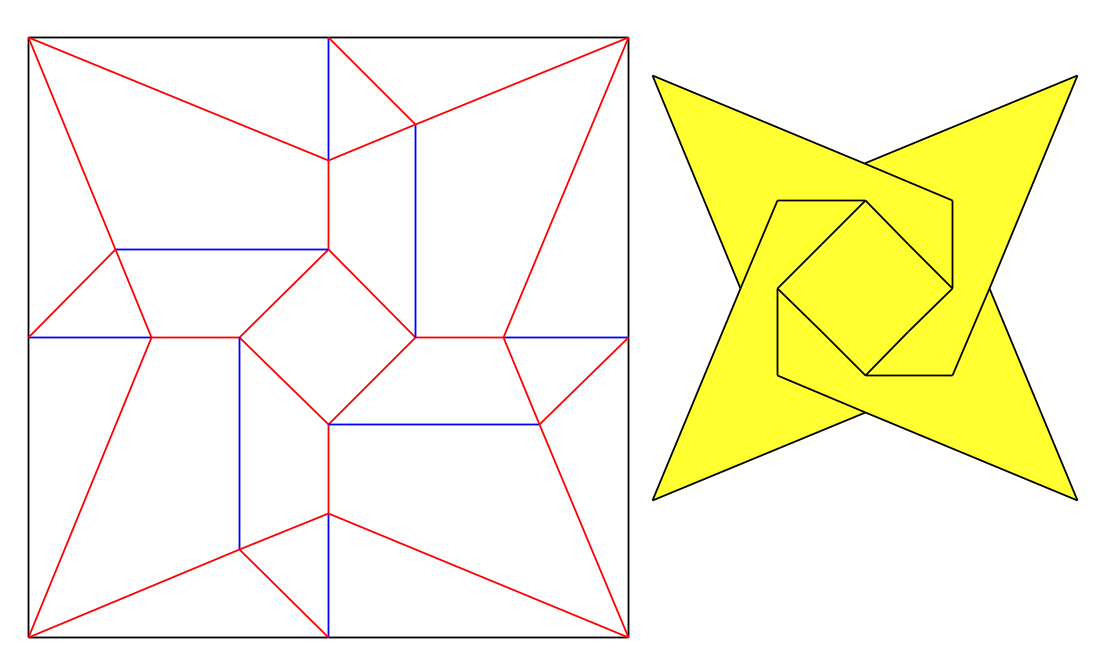

This is actually quite a late post, the original design was completed almost two months ago. Nonetheless, I intend to explain as thoroughly as possible the process of its design. (Above can be found the crease pattern, as well as a collapse sequence for a simplified base. More detailed instructions can be found published in the 2024 OrigaMIT Convention Book.)

After folding Riccardo Foschi’s sitting gnome, I found the layer build-up to be quite significant, and was unimpressed by the final size of the model relative to the starting sheet. Desiring a gnome with greater detail, and to my great chagrin, finding no such model existing, I set out to make my own.

The first enterprise was to determine the desired features. As I lack the patience to make sketches of the intended form, I simply decided that I wanted a round nose, a full beard, eyes, ears (very important), the characteristic pointy hat, all four limbs, and something for the gnome to sit on.

I had previously explored a structure for faces from a bird base. While chowing down lunch, I realized I could flip the structure upside down. I could use one corner of the bird base for the gnome’s pointy hat, one for the beard, and the other two for the ears. The central flap would be split to make the nose and brow.

This solved the issue of how to obtain the gnome’s most defining characteristics quite rapidly. In my sloth, I fitted the head into a 3×3 grid, and slapped together some basic 22.5 molecules to fabricate arms and legs.

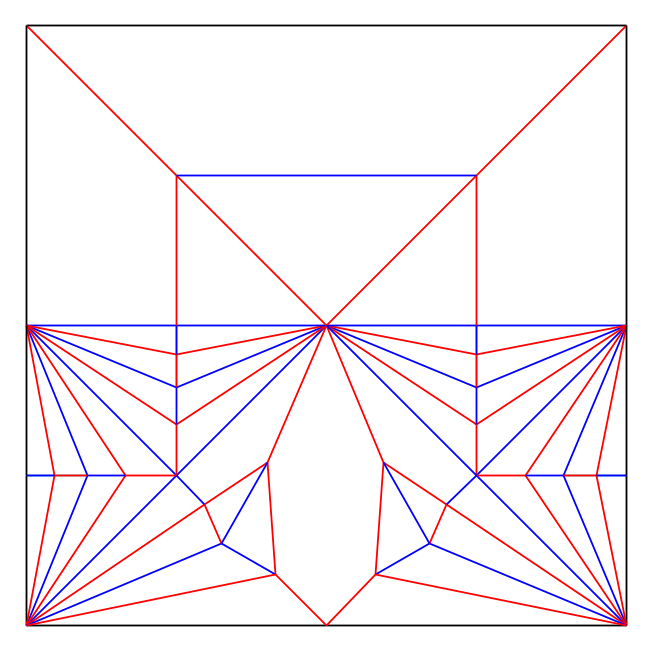

The downside of this structure was that the bottom right corner of the paper was unused. This was a fairly sizable amount of paper. In addition, I disliked the relative stubbiness of the arms and legs. If I could shift the leg flap towards the bottom right corner of the paper, I could elongate the leg flap while absorbing some unused paper. I fiddled around with 22.5 degree structures and proportions for a day or two with no success.

The downside of this structure was that the bottom right corner of the paper was unused. This was a fairly sizable amount of paper. In addition, I disliked the relative stubbiness of the arms and legs. If I could shift the leg flap towards the bottom right corner of the paper, I could elongate the leg flap while absorbing some unused paper. I fiddled around with 22.5 degree structures and proportions for a day or two with no success.

At this point, fed up, I returned to the thirds I had previously, and added some elements to shift the 22.5 degree creases into diagonal pleats terminating at the bottom right corner of the paper.

A quick Elias stretch produced long legs and some extra paper that, as I eventually learned, could be folded up to close up the seam (a seam is the region where edges of the paper meet, exposing an unintentional color change).

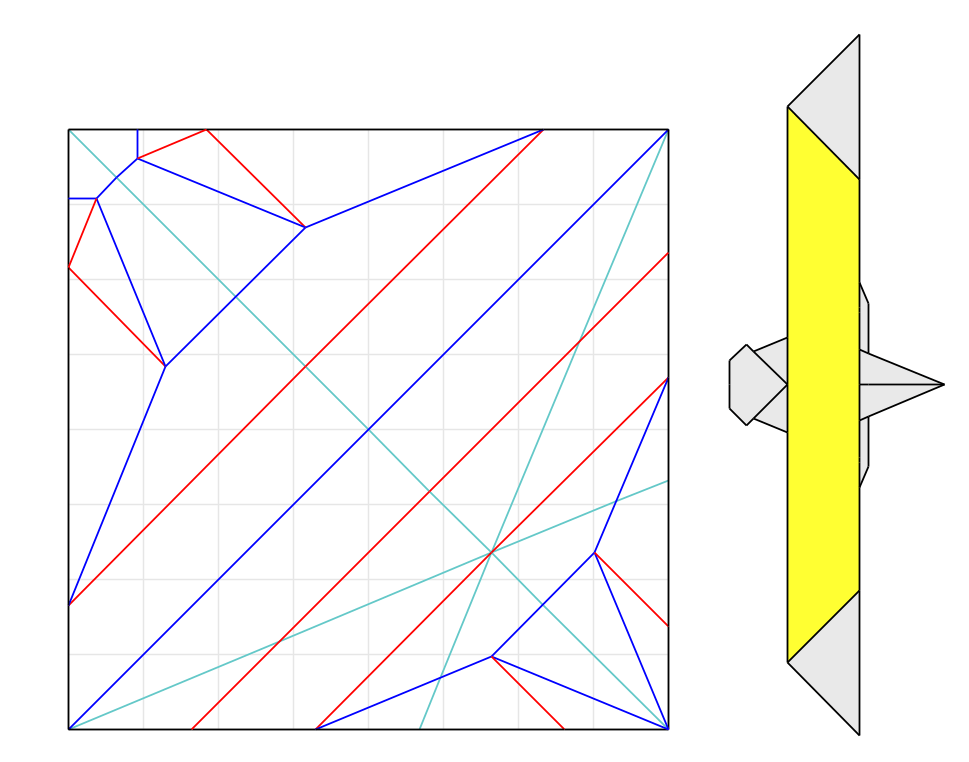

After collapsing I realized that I needed to thin all the flaps.

Which I promptly did.

At this point I was rather satisfied by the base, and my excitement almost eclipsed my dismay over being unable to use a structure fully based in the irrational proportions of 22.5 degrees.

Here is a picture of my first test-fold of this base.

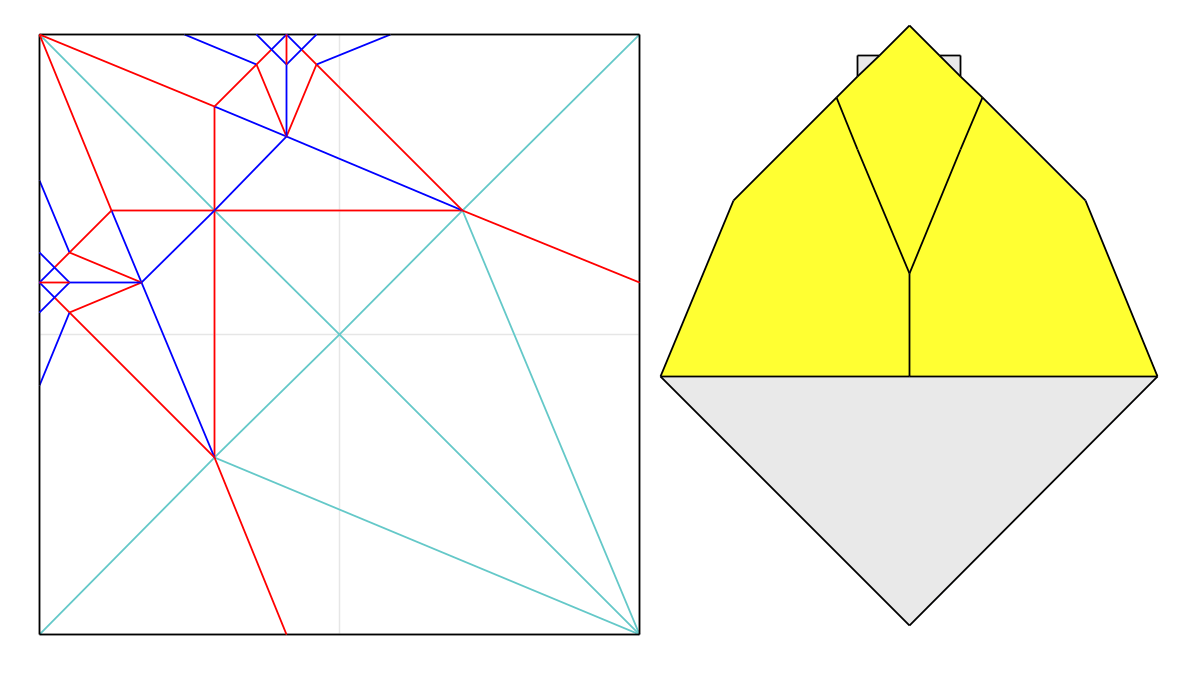

I made a sheet of burgundy double tissue, and figured out the shaping more or less as I went, with the aid of two test folds. As I had not added a mouth structurally, I struggled with finding one that was of the right size and that was not too cartoonish.

I settled after much dilly-dallying with a simple pleat, which makes him look rather sullen, in an amusing sort of way. (Imagine a minute gnome glowering at you. ‘Tis more entertaining than intimidating.)