2015 – 2018 | 35 m | United States | Written and Directed by Maribel Apuya

Date: Friday, October 27, 2023 | 7:00 PM

Venue: NYU King Juan Carlos Center | 53 Washington Sq S, NYC 10012

Free and open to the public.

RSVP Link: http://bit.ly/panawin2023f

Synopsis

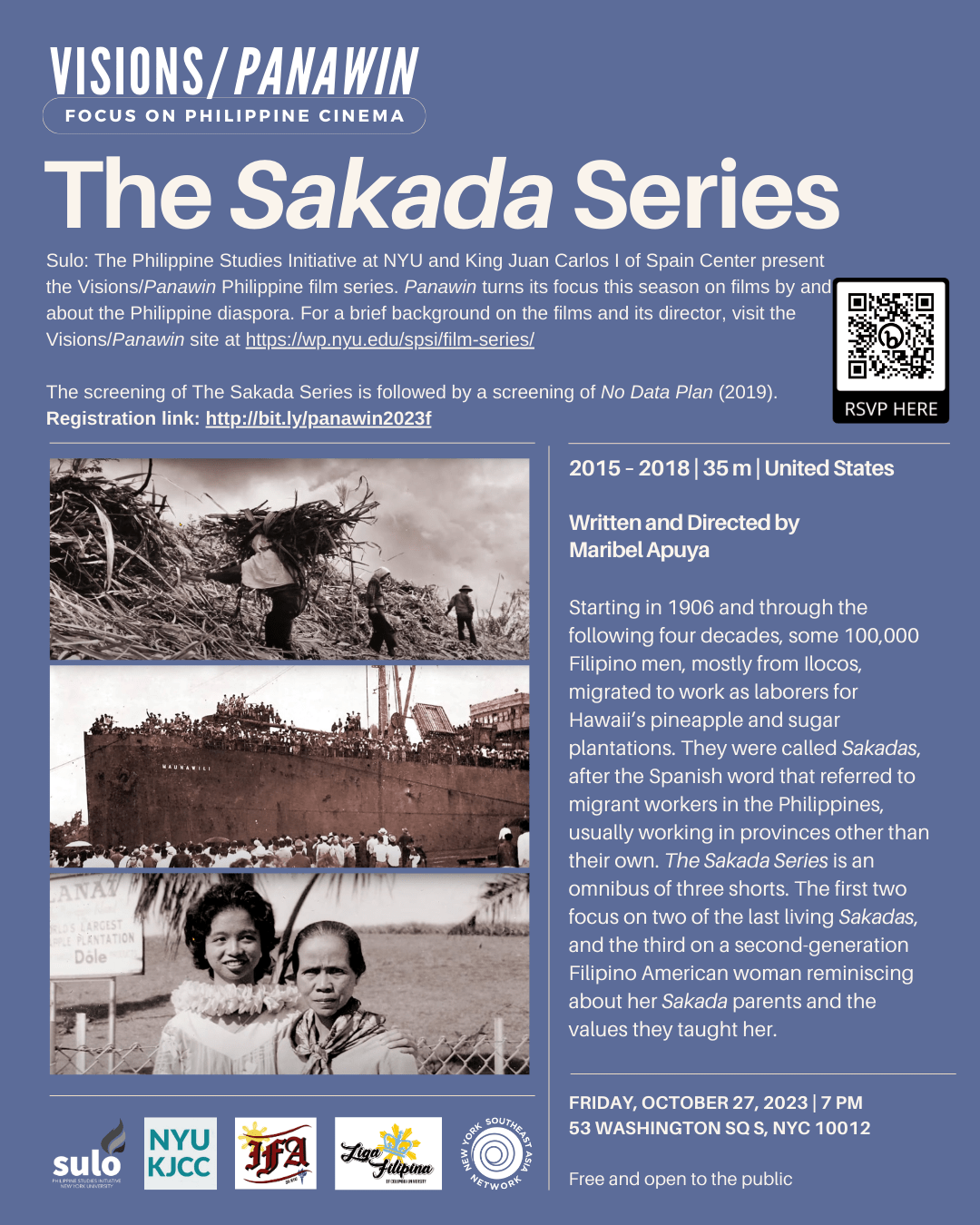

Starting in 1906 and through the following four decades, some 100,000 Filipino men, mostly from Ilocos, migrated to work as laborers for Hawaii’s pineapple and sugar plantations. They were called Sakadas, after the Spanish word that referred to migrant workers in the Philippines, usually working in provinces other than their own. The Sakada Series is an omnibus of three shorts. The first couple focus on two of the last living Sakadas, and the third on a second-generation woman reminiscing about her Sakada parents and the values they taught her.

Notes on the Film

The first Sakadas arrived in Honolulu on December 20, 1906, probably already missing the upcoming Christmas celebrations back home in Ilocos. The last Sakada recruits, some 6,000 migrated in 1946 just before the Philippines gained independence, formally at least, from the United States. It was only in 1959, over a dozen years after the last Sakada arrivals, that Hawaiians overwhelmingly voted for statehood.

So the Sakadas were actually not migrating to the United States, but were moving from one US colony to another, as the internal Philippine Sakadas had been migrating for generations from one province to another, driven by dreams of better lives but often crushed by the realities of feudalism and colonialism. The Dole company that recruited Filipinos for the Hawaiian plantations (and spearheaded the US colonial takeover of the Hawaiian kingdom) was the same Dole company that recruited migrants from other parts of the Philippines to Mindanao. Sakadas, unable to earn enough with their subsistence wages to return back to their home province or country, ended up staying put and making the best of their lives in the new land, stoically passing down dreams postponed to their descendants.

Due to the Sakada influx, Filipinos, even before factoring in mixed Filipinos, make up about 1/4th of Hawaii’s ethnic population, its largest. The Sakada Series is filmmaker Maribel Apuya’s valentine to the Sakada old-timers that she interacted with while growing up in Hawaii.

Although there are references to the backbreaking work in the plantations, the low and unfair wages, and the fight for labor rights as members of the ILWU (International Longshore and Warehouse Union), the shorts are mostly an assembly of personal recollections by two of the last surviving Sakadas, Cipriano Erice and Angel Ramos, both part of the last migration in 1946, as they look back with satisfaction at having provided for their families and improving their lot in life, and in the case of Erice, playing a leadership role in the local labor union.

These shorts are followed by the recollections of Apolonia Agonoy Stice, a second-generation descendant who became a trailblazer herself as one of the first Filipino-Hawaiian teachers. Beyond the interviews and old family pictures, the shorts feature archival photos of Sakadas arriving in Hawaii, toiling in the plantations, and joining marches for better working conditions.

Apuya’s aim is to preserve these often humble voices and images, almost like family photo albums, before time erases them, rather than compose a hard-hitting analysis of imperialism, labor exploitation, and racism that were undercurrents in the mass migrations of low-wage workers at the height of Western colonialism. Instead, the shorts focus on the personal dreams for better lives that impelled the Sakadas to venture into an unknown future and sustained them and their families in a new and harsh life; and on the values of respect for elders, devotion to family, and willingness to work that they bequeathed to newer generations of the Philippine diaspora.

— Gil Quito, Curator

Notes on the Director

Maribel Apuya was born in the Philippines and grew up in Hawaii. She graduated from the University of Hawaii as a Presidential Scholar and a National Foundation Scholar. She trained in theater performance in New York City and graduated from UCLA School of Theater, Film, & Television’s Professional Program in Screenwriting. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing for the Performing Arts from the University of California, Riverside.

Awards

- Honolulu Film Awards – Best Documentary Short

- Impact DOCS – Award of Merit

- DisOrient Asian American Film Festival – Heritage Award

- North American Film Awards – Special Jury Award

- Docs without Borders Film Festival – Exceptional Merit Award

Additional Links

Brief History of the Sakadas (from the Sakada Series website)

Between 1906-1946, over 100,000 Filipino men were recruited by the Hawaiian Sugar Planters’ Association to work as Sakadas for Hawaii’s booming sugar plantation industry. The final wave of labor migration took place in 1946, with 6,000 Filipino men immigrating to Hawaii.

By 1932, Filipinos became the backbone of plantation labor, making up 70% of the plantation workforce. Viewed primarily as instruments of production, they performed the most labor-intensive jobs (such as manually cultivating and hauling cane) and were paid less than other ethnic groups – an annual average of $467 in 1938, compared with $651 for Japanese workers, according to a 1939 Bureau of Labor Statistics report.

In addition to performing backbreaking work, the Sakadas found resourceful ways of living, including planting their own food, fishing, and working extra jobs – while still sending money to the Philippines to support their families there. At the onset of the Great Depression in 1929, Filipino workers in Hawaii collectively sent $276,000 to the Philippines each month.

The Sakadas played a lead role in the fight for labor equality within the plantation system; as the backbone of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU), their support in numbers, courage, and resilience ensured the victory of union strikes.

The Hawaii State Legislature recently passed a bill enacted into law proclaiming December 20th of each year as “Sakada Day” in Hawaii. The bill recognizes the historic significance of the Sakadas as great pioneers who, through their sacrifices and struggles, paved the foundation for the establishment of the Filipino community in Hawaii and helped to shape the diverse Hawaii we have today.