2019 | 1 hr 10 m | United States | Written and Directed by Miko Revereza

Date: Friday, October 27, 2023 | 7:00 PM

Venue: NYU King Juan Carlos Center | 53 Washington Sq S, NYC 10012

Free and open to the public.

RSVP Link: http://bit.ly/panawin2023f

Synopsis

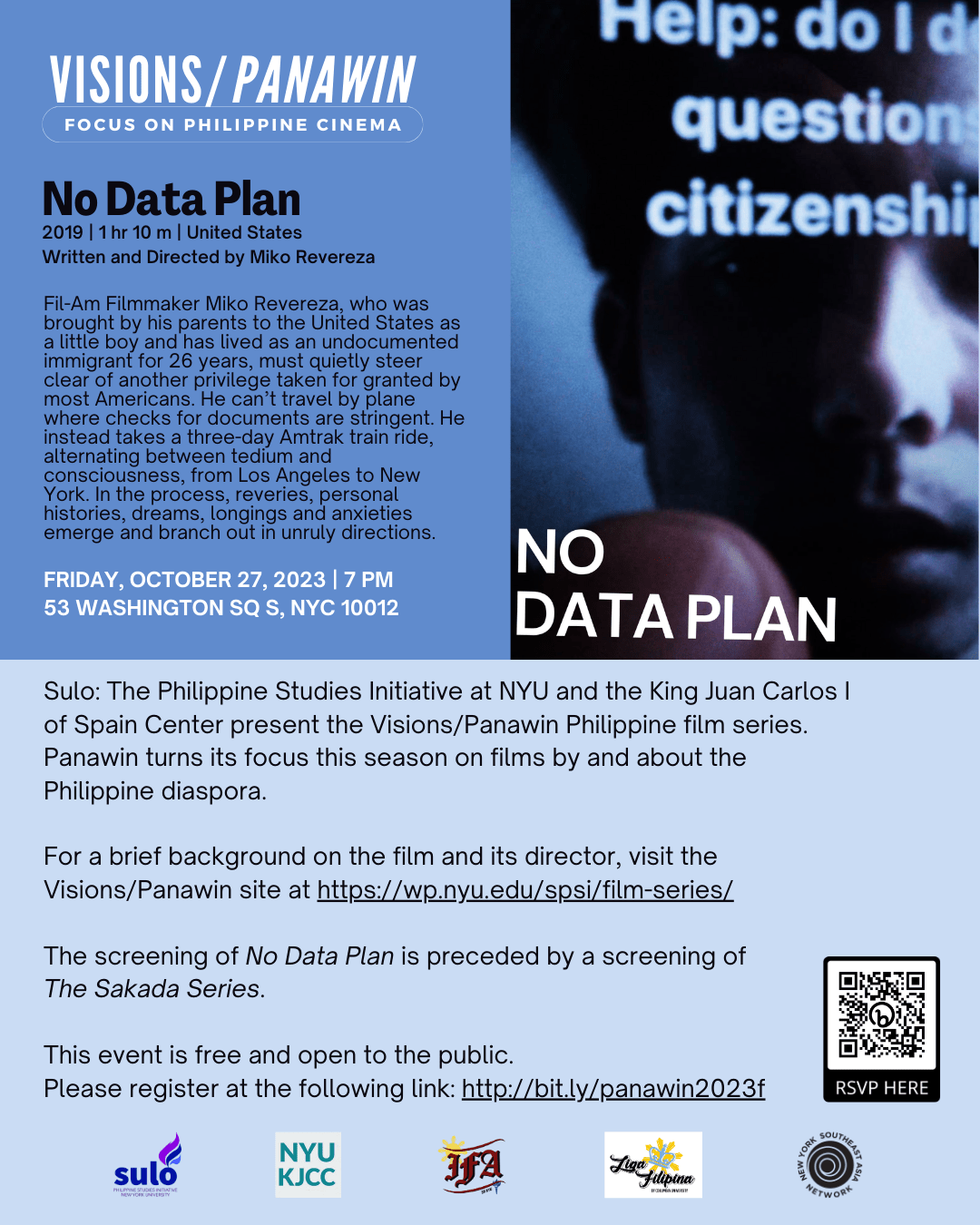

Fil-Am Filmmaker Miko Revereza, who was brought by his parents to the United States as a little boy and has lived as an undocumented immigrant for 26 years, must quietly steer clear of another privilege taken for granted by most Americans. He can’t travel by plane where checks for documents are stringent. He instead takes a three-day Amtrak train ride, alternating between tedium and consciousness, from Los Angeles to New York. In the process, reveries, personal histories, dreams, longings and anxieties emerge and branch out in unruly directions.

Notes on the Film

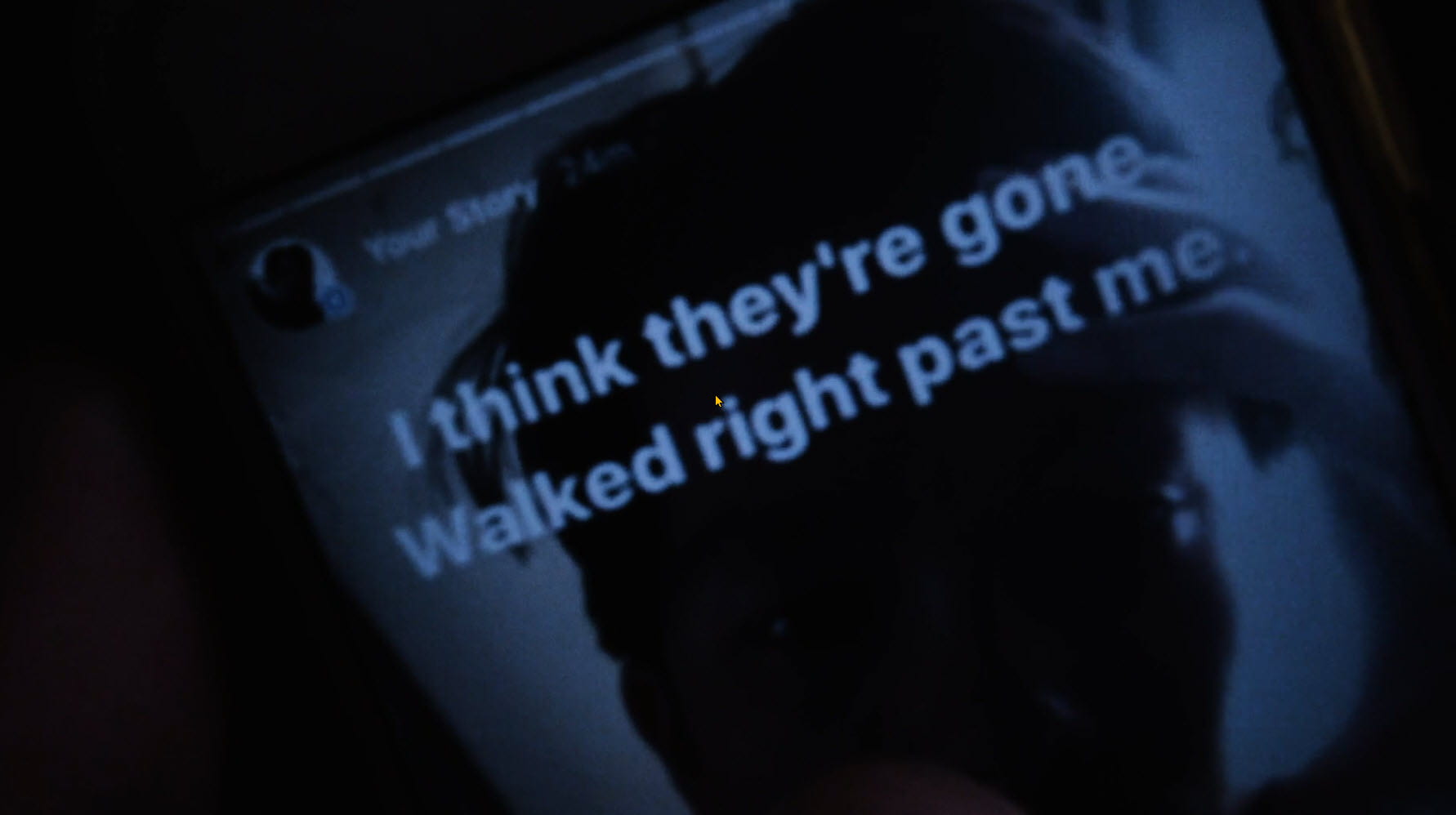

No Data Plan starts with anonymous shots of a crowd boarding the Amtrak train in LA. A voiceless narrator, cryptically communicating through subtitles that appear intermittently on the screen, states: “Mama has two phone numbers. We do not talk about immigration on her Obama phone. For that we use the other number with no data plan.”

Revereza had no plans to make the film that eventually became No Data Plan. Disappointed that the Amtrak train had no WiFi despite the advertising, he filled the time unobtrusively recording random, impersonal shots with a small Sony DSLR camera strapped around his neck. As he went through the footage afterwards, the beginning and near-end of the journey suggested some sort of a pattern, with a ticket officer demanding ID’s at the start, and at the film’s climax in Rhinebeck, NY, a random check by ICE Border Patrol with Revereza saying to himself, “(Expletive), this is it. This is where they catch up to me.”

The result was a paradoxical marvel of filmmaking – an experimental film that turns out to be as attention-getting in its own weird way as a suspense thriller and, with the story of his mother’s affair with a younger Vietnamese immigrant with ties to a crime syndicate, a domestic melodrama.

Revereza’s filmmaking breaks all the rules of Hollywood storytelling, rules that, one might say, are mostly products of documented white heteronormative dominance. When he talks about himself or his parents or the Vietnamese lover, we never see them. The stories are generally accompanied by images of cargo vans passing by, stains on unwashed windows, desolate way stations, or bodies getting on and off the trains. In fact, the images, at times decidedly mundane and not passable even for Instagram posts, have mostly no logical or direct connection to the stories being told. (The one exception is at the climactic passage with the ICE Border Patrol.) Instead, they seem to function as blank or abstract environments that provide scope for the stories to forge a haunting resonance. The disjoint between image and story heightens the sense of someone hiding in anonymity, as undocumented immigrants are wont to do. In the process, Revereza shows himself finding a new cinematic language, that of an excluded immigrant aesthetic where any object or pattern at hand could get included into an art that would move and amaze.

Occasionally, one hears audio of Revereza’s mom talking about the exalted position the family fell from after leaving the Philippines for the United States. She speaks of how Revereza’s father was already a bank Vice President before he decided to emigrate. She reminds him that the family came from ancestors of high social standing (the gobernadorcillo class) where some servants would decline wages, only grateful that they could be accepted as part of such a family and enjoy a sense of pride above the other servants.

There are only two brief intervals in the film when we hear Revereza’s speaking voice. The first is when he recounts a persistent dream of flying to the Philippines into a crowded airport, arduously making his way through the crowd, and somehow getting stuck permanently outside the airport. The second happens near the end, when he narrates the tense moments with the ICE Border Patrol. It’s also the only time we see Revereza’s face, albeit through a blurry glimpse on his cel phone.

Afterwards. the voiceless narration returns, relating how he tells his mother his plan of leaving the States in a year. “I can tell she believes me. She weeps through the shitty speaker. ‘I just wish I could do that too.’”

Revereza did in fact follow up on the plan, buying a one-way ticket to the Philippines, in an attempt to get to the roots of his parents’ obsession with America. In his new film Nowhere Near, he documents how he finds some of these roots in the miasmic traces and ruins of the Spanish and American empires that continue to haunt the country and its diaspora.

Notes on the Director

Miko Revereza is an experimental filmmaker born in Manila (1988) and brought by his mother to Los Angeles in 1993 to join his father who had immigrated three years earlier. Despite working with a lawyer, the family’s immigration status went nowhere and Revereza would grow up as an undocumented immigrant, gradually learning his limitations as one of the “excluded” in his own country. Navigating through the fraught and risky labyrinth of his status, he managed to earn an MFA in filmmaking from Bard College, despite having no undergraduate degree.

He made a series of experimental shorts before producing No Data Plan which caught worldwide attention after it premiered at the True/False Film Festival.

He followed this up with Distancing (2019), a short film dealing with the logistics of travelling to the Philippines in the face of his undocumented status and The Still Side (2021), about a mythical Philippine sea creature’s emergence at an abandoned Mexican island resort.

Nowhere Near, his full-length sequel to No Data Plan, that charts his journey from LA to his ancestral province of Pangasinan, premiered to critical acclaim in September at the New York Film Festival. Unable to come back to the United States for the next 10 years after his risky trip to the Philippines, Revereza is currently based in Mexico.

Revereza is the recipient of the Vilcek Prize, which recognizes immigrants who have made major contributions to American society and heritage in the sciences and the arts.

— Gil Quito, Curator

Awards

- Gawad Urian – Best Documentary

- Taiwan International Documentary Film Festival – Merit Prize

- Sheffield International Documentary Festival – Art Doc Award