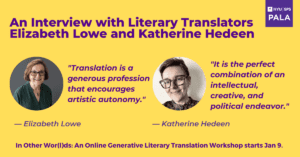

Elizabeth Lowe and Katherine Hedeen co-teach the NYU SPS PALA course In Other Wor(l)ds: An Online Generative Literary Translation Workshop, which starts January 9th. Lowe is an erudite translator and writer. She’s published books on Latin American culture, including The City in Brazilian Literature (1982) and Translation and the Rise of Inter-American Literature (2007). Lowe has received many accolades, recently the NEH Literary Translation Grant in 2020-21 and a 2022 Fulbright appointment to Brazil.

Hedeen specializes in Latin American poetry and has established herself as a forefront translator of this region. She has been a finalist for the Best Translated Book Award and the National Translation Award, as well as a recipient of two NEA Translation grants in the US and a PEN Translates award in the UK.

We had the opportunity to speak with Lowe and Hedeen about the art of translation, and what students can expect from their upcoming workshop.

What can students expect from the In Other Wor(l)ds workshop?

EL: Participants will work with a diverse, international cohort of translators in both synchronous and asynchronous sessions, to generate new translations, workshop with the group, perform bilingual readings, and process feedback to their translations to ready them for publication. The workshop seeks to promote a collaborative, supportive, and enriching environment that will encourage participants to become a part of the larger translation community, and to expand their networking skills. In addition to practical information about translation and the translation world, we will focus on the aesthetics of translation, the agency of the translator as a socially engaged member of the artistic community, and the joy of translation as an act of creative writing.

What language skills do students need to take the workshop?

EL: Students must feel confident about their writing skills in English, and have a highly proficient reading ability in their source language.

What is your favorite part of teaching this workshop together?

EL: Kate and I have established a dynamic creative partnership over the past years, which began with our founding the Kenyon Review translation workshop. We bring not only different genre perspectives to the art of translation (Kate specializes in poetry and I work with fiction and creative non-fiction), but we also have life experiences in the field that reflect the path of two generations. Kate and I are aligned philosophically about the importance of the intellectual and artistic freedom of the translator, and we also benefit from sharing the work we do in different languages and world regions. As a mutually supportive partnership, I believe we model the best of translator collaboration and nurturing, which is an important value we seek to impart to our participants.

In your words, what does it take to be a literary translator?

EL: In the words of Gregory Rabassa, I prefer to be thought of as a writer. It takes a keen interest in other languages and cultures, curiosity about the plasticity and wonders of language itself, a dedication to writing practice, and a personal mission to be an agent of cultural change and growth.

KH: For me, it’s all about passion. Passion for knowing, reading, writing. This is what drives all writers. It’s no different for literary translators.

Why is the art of literary translation important to you?

EL: Jhumpa Lahiri, in her recent book Translating Myself and Others, writes of translating as “looking into a mirror and seeing someone other than oneself.” Translation is a creative practice that I have cultivated my entire professional life; it has grown with me, and helped me grow. As an avid reader, I apply the lessons learned in reading to my creative writing practice and my teaching, which require a totality of focus. Translation is an art that keeps one connected to the world, demanding alertness to what others are experiencing and writing. I relish the personal ties I have made with writers, and take pride in expanding their readership. I likewise receive immense pleasure in teaching and mentoring rising translators. Translation is a generous profession that encourages artistic autonomy, and I like to think that my work plays a part in enlarging the community of readers, writers, and translators.

KH: It is the perfect combination of an intellectual, creative, and political endeavor. It is an amazing way to approach knowing as well as to recognize all the things we don’t know. Translators are generous; they create connections.

Read on below for two excerpts of Lowe and Hedeen’s translations!

Entre facas, algodão, de João Almino

The Last Twist of the Knife, by João Almino

Translated by Elizabeth Lowe

Dallas: Dalkey Archive Press, 2021

April, Easter

April 21

Clarice is the exception. My memory of her is as clear

as a photograph kept with care in the bottom of one of

my drawers. In it she looks at me with an expression that

I feel is one of love, and which even today sends quivers

through my body.

I recover pieces of myself to create this contradictory

and true story that torments me. That’s why I have to

share it. It is as contradictory and true as the backlands;

my mother punished me and protected me, and my

godfather, Clarice’s father, was severe and affectionate.

I accepted their mood changes the same way I accepted

the mood changes of nature. I thought my joys and

sorrows were normal.

In winter, rain covered the green land, our boots

trampled mud over the floor, the conversation and

laughter lingered on the porch of the big house of my

godparents, the songs of the cowboys rose up from the

pastures, the mosquitos bit me in our red brick house.

I’d roll myself up in the hammock, cover myself with

the sheet, leaving just my nose exposed, and listen to the

raindrops on the roof.

At the height of the drought, the merciless sun pun-

ished Black Creek Ranch and blinded me. The dust

whipped the gray fields, with its bare trees, dazed people

stewing with irritation in the heat, the wells were dry,

the reservoir and the barn were empty, the cattle had

migrated to Piauí.

Here again I might be mixing up time periods.

Forgive me. I may be conflating the drought of one

year with the prolonged summer of another. But I’m

not inventing anything; at most it’s my memory that

betrays me here and there. It’s my age; at seventy your

memory falters. What is true is that the landscapes of

the drought always display the same calcified trees, the

same ashen ruins and the same irritation. I think that

above all it is the landscapes of the drought that brand

backlands people like me.

Original Portuguese:

Abril, Páscoa

[21 de abril]…

Clarice é exceção. Minha lembrança dela é nítida como a fotografia bem guardada

no fundo de uma de minhas gavetas em que ela olha pra mim com olhar que sinto ser

apaixonado e até hoje transmite vibrações por meu corpo.

Recupero pedaços de mim para criar esta história contraditória e verdadeira, que me

atormenta. Por isso tenho que pôr pra fora. Como contraditórios e verdadeiros, além do

sertão, eram mamãe, que me punia e me protegia, e meu padrinho, pai de Clarice,

severo e carinhoso. Eu aceitava as mudanças de humor deles como aceitava

mudanças de humor da natureza. Achava normais minhas alegrias e tristezas.

No inverno a chuva cobria o campo verde, o chão ficava marcado com o barro das

botas, as conversas e risos se prolongavam no alpendre da casa-grande de meus

padrinhos, os aboios se animavam no campo, as muriçocas me picavam na nossa casa

de tijolo aparente e vermelho, eu me enrolava na rede e envolvia o rosto com o lençol,

deixando só o nariz de fora e ouvindo os pingos bater nas telhas.

Já na seca, o sol impiedoso castigava a fazenda do Riacho Negro e me cegava a

vista. A poeira açoitava os campos cinzentos, de árvores despojadas, o açude

minguado, as cacimbas sem água, as pessoas zonzas cozinhando irritação no calor, e

o curral vazio, o gado tangido para o Piauí.

Nisso pode ser que de novo misture tempos, me descuplem, a seca de um ano com

o verão prolongado de outro. Mas não invento nada, no máximo é a memória que me

trai aqui e ali, coisa da idade, aos setenta anos a memória falha. O que é certo é que

as paisagens da secura traziam sempre as mesmas árvores calcinadas, a mesma ruína

cinzenta e a mesma irritação. Acho que são sobretudo elas, as paisagens da secura,

que marcam os sertanejos feito eu.

Epitafio del extranjero vivo, de Jorgenrique Adoum

Epitaph of the Living Foreigner, by Jorgenrique Adoum

Translated by Katherine Hedeen and Víctor Rodríguez Núñez

Action Books, 2021

with hunger and hembra this hombre

his reality surreal

dispictured in his passport

discontent in this discontext

working and worqueen

to be deagonizing from badlyloved

even wanting to disencruel himself

to stand erect to correct and recorrect himself

but this republic public sepulchershop

doesn’t give him enough time

and he keeps redying in a virtuous circle

from his long inhurting disdeath

Original Spanish:

con hambre y hembra este hombre

surreal su realidad

desretratado en su pasaporte

descontento en este descontexto

trabajando y trasubiendo

para desagonizarse de puro malamado

queriendo incluso desencruelecerse

pararse a reparar y repararse

pero no le da tiempo

esta república sepulturería pública

y sigue remuriendo en un círculo virtuoso

de su larga desmuerte enduelecido

Sign up for Lowe and Hedeen’s course, In Other Wor(l)ds: An Online Generative Literary Translation Workshop.