Earlier this year, I was approached by the editor of a small, specialized publication for a general readership who had read my review here of The Myth of the Andalusian Paradise and on that basis asked me to write something for his web magazine. I was thrilled, sent him a little abstract, we agreed on the topic, and I was off. It’s a newish publication and the editor not, as far as I can tell, especially experienced; and by the time he asked me to rewrite the entire thing for the third time, contradicting edits he had made in earlier versions, futzing for the sake of futzing, and trying to make my writerly voice sound like his, I withdrew the piece. He deplored my “lack of commitment to the process,” (that sound you hear is me scoffing, indignantly) and the whole experience left a lot of bad feeling all around. I gather, through the grapevine, that I am not the only person to have had such an experience with this publication. Because it was written specially for a specific publication (and because it’s an approach I don’t really want to take in my own work and writing — looking at medieval history through a lens of anti-Semitism) I’m not sure that I’ll have much success in placing it elsewhere; and on top of that, I’m just not in the mood at the moment to sell myself and my work in the way that one has to do to attract the attention of the editors of general publications. And yet, I have this thing sitting on my hard drive and I wouldn’t mind clearing it from my mental plate. So I’ve decided to share it here. What’s the point of having one’s own web publishing platform if not for that? Plus, I’ve been working on a short blog post that’s related and that I will post by the end of the week, so it’s thematically appropriate for this moment in this space. Plus plus, since I’m already sharing some of the materials that will make up my next book, it fits in that way, too. It’s a long piece (it would have appeared in two parts had it run in the publication that commissioned it) and it’s designed for a general audience, so I hope that lay readers will enjoy it and that the academics who float through here on occasion will see some merit in it, too.

Part I

The Hebrew poets of medieval Spain were the rap and hip-hop artists of their day. In the public performances of their verse, often at the fanciest parties with the finest liquor, they declaimed their opinions on social and political issues that affected them, imbuing their work with their victories and sadnesses; they praised themselves and their skills, caught beef with their peers, and did not let those rivalries die; they sampled the beats of the Arab poets working around them; and they irreversibly altered the properties of the Hebrew language in which they composed. They were complete badasses, they knew it, and they rhymed about it. What they perhaps could never have anticipated was the extent to which their poetry would speak so directly to the concerns of readers who would follow them into the world by a thousand years. But reading with a modern eye, it is immediately clear that many of the struggles that medieval Hebrew poets faced over language choice and national identity — over how to belong — were strikingly modern in their character and they poured out in their strikingly modern verse.

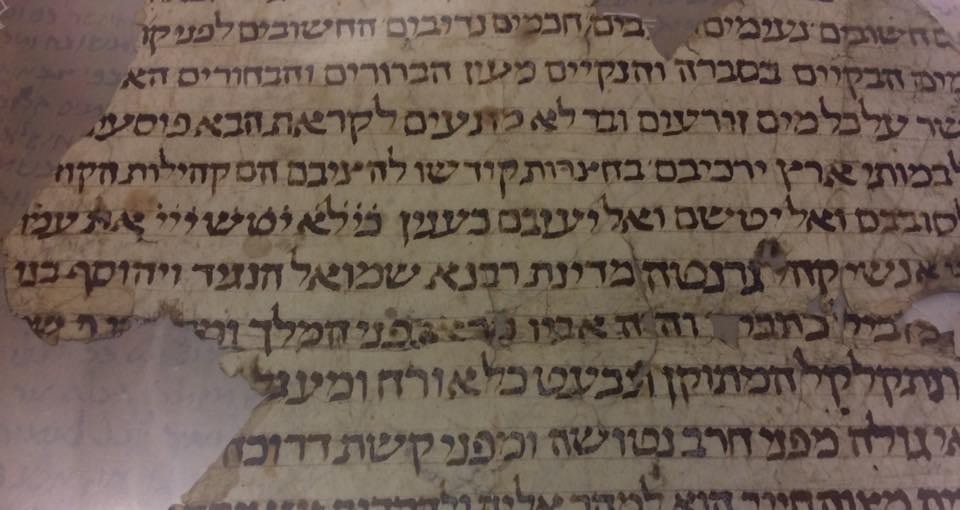

One of these poets was Samuel ibn Naghrīla (d. 1055-6) who served as a vizier and general to the Muslim emir of Granada but was also the leader, or nagid, of that city’s Jewish community and the best of its poets. He earned himself the nickname “twice the vizier” for his military and poetic prowess. His poetry covers topics from fatherhood to the battlefield to the value of both healthy and pleasing foods; some of his most significant poems were written to and about his beloved son Yehosef would succeed him as both the nagid and a government official in Granada. Samuel’s own writings and those that survive that tell his story from others’ perspectives demonstrate that he was deeply engaged with both Jewish and Muslim thinkers and cultural leaders of the day and with their ideas. His poetry is secular in nature but written in what medieval Jews considered to be the divine language — Hebrew — and drew often and strongly on biblical and other religious language, all the while using the rhyme and meter schemes of his Arabic-speaking Muslim counterparts.