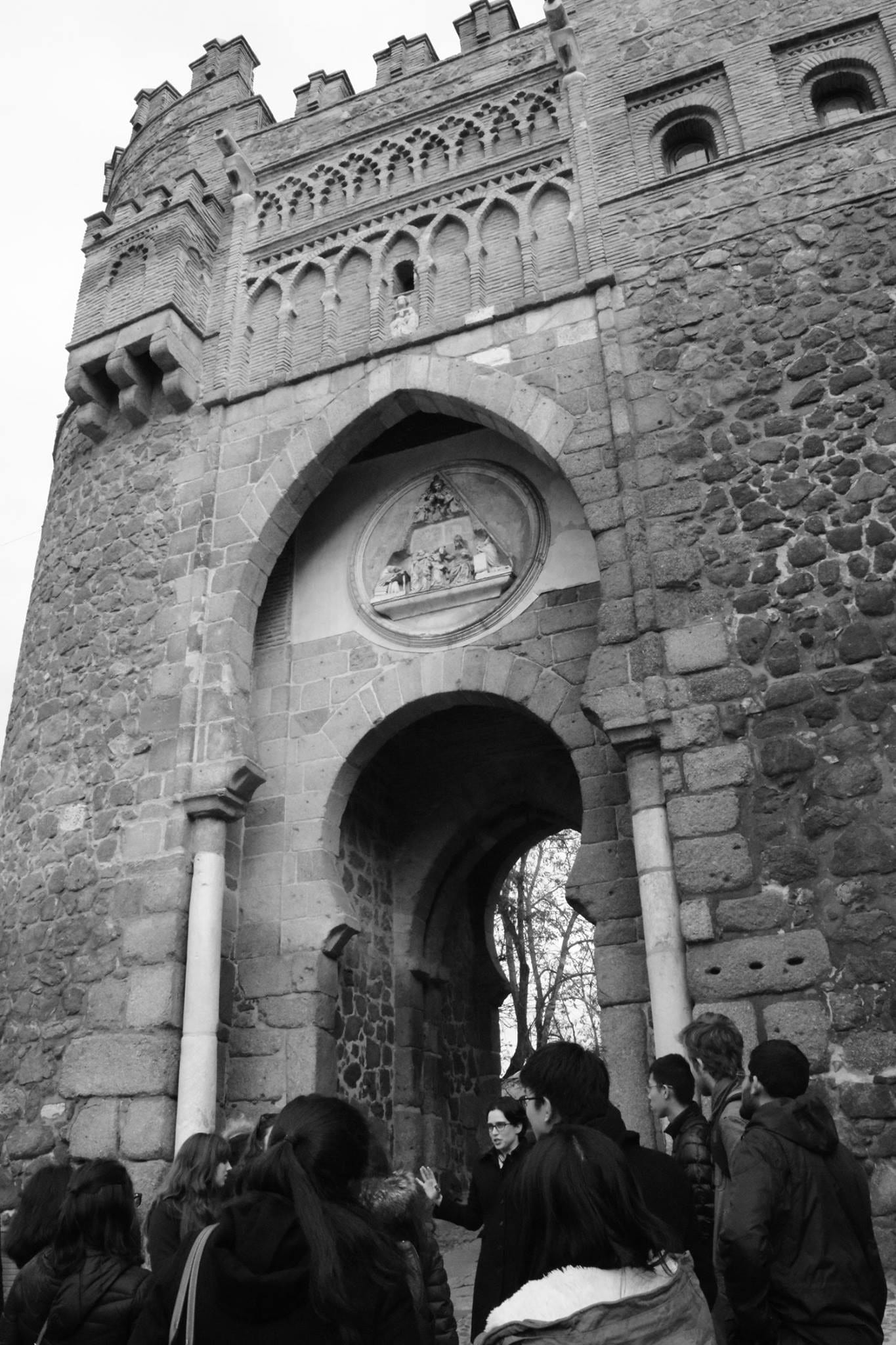

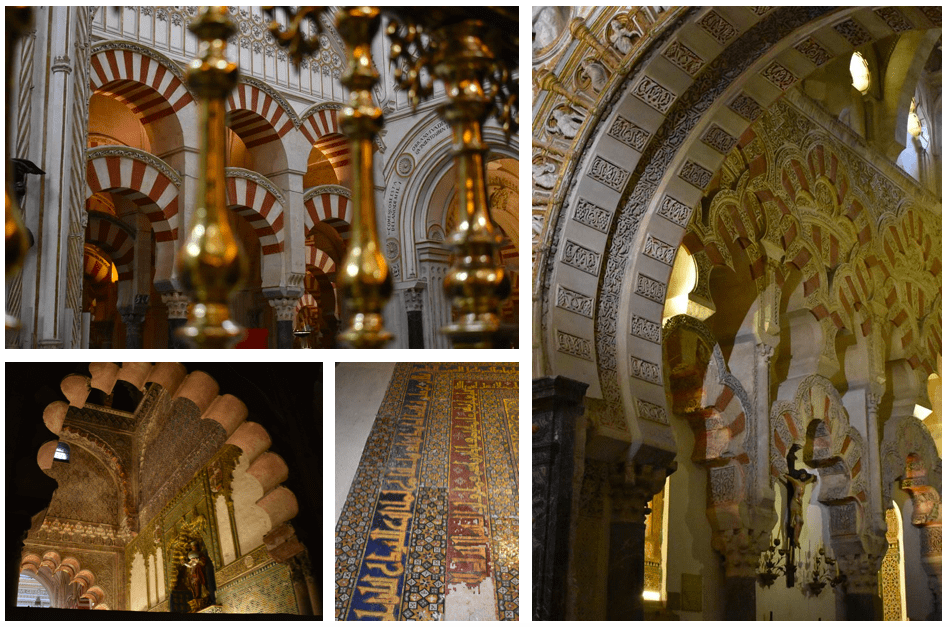

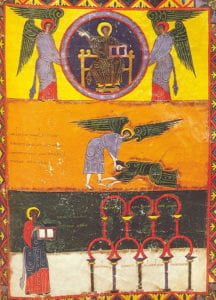

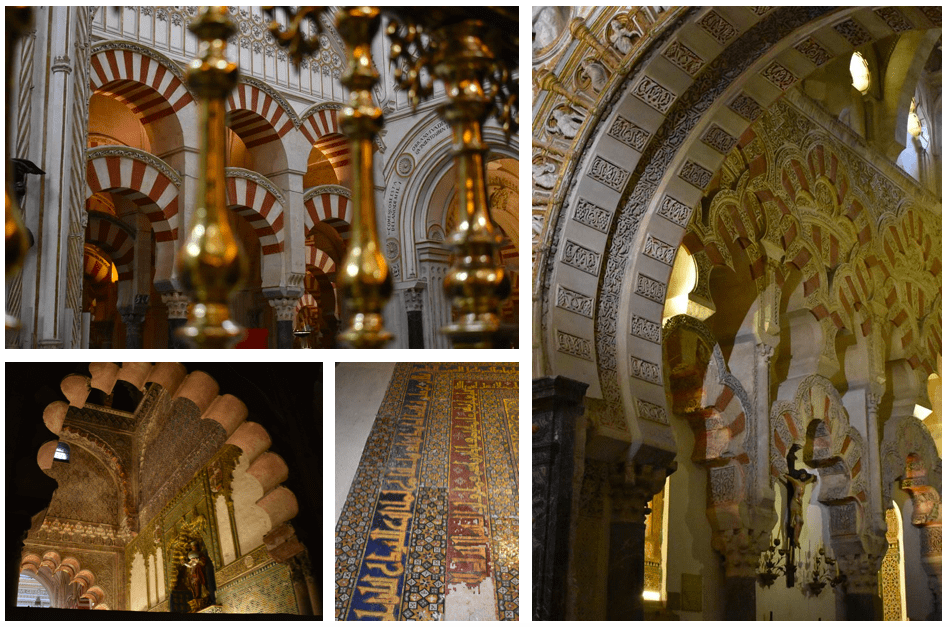

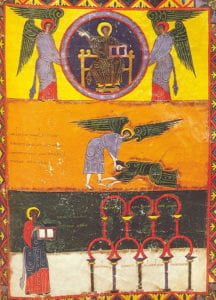

Some views of the Great Mosque of Córdoba, a building that is all modern significance, and always has been. At the moment it was built it signified an attempt to unify a fragmented Muslim community that included military rulers who had been left to do their own thing until the center of power moved west in the middle of the 8th century. It came to symbolize Córdoba during the period of the Umayyad emirate and caliphate, when it became the visual touchstone for al-Andalus (about which the art historian Susana Calvo Capilla has written — Las mesquitas de al-Andalus — and which is quite self-evident in the illuminations of the Beatus commentary on the apocalypse). When Fernando III took the city of Córdoba in 1236, the building was converted into church and left, architecturally, just as it always had been because it was the modern look for buildings of all sorts. When modern aesthetics turned to the Europeanizing and the baroque, Charles V plunked a baroque cathedral down in the center of the building.

Some views of the Great Mosque of Córdoba, a building that is all modern significance, and always has been. At the moment it was built it signified an attempt to unify a fragmented Muslim community that included military rulers who had been left to do their own thing until the center of power moved west in the middle of the 8th century. It came to symbolize Córdoba during the period of the Umayyad emirate and caliphate, when it became the visual touchstone for al-Andalus (about which the art historian Susana Calvo Capilla has written — Las mesquitas de al-Andalus — and which is quite self-evident in the illuminations of the Beatus commentary on the apocalypse). When Fernando III took the city of Córdoba in 1236, the building was converted into church and left, architecturally, just as it always had been because it was the modern look for buildings of all sorts. When modern aesthetics turned to the Europeanizing and the baroque, Charles V plunked a baroque cathedral down in the center of the building.

Its red and white striped arches are still a visual short-hand for the region. And it is the site that most closely reflects the debates about Islam, religion, and history in the peninsula in the contemporary period, about which my colleague Eric Calderwood has written about it: The Reconquista of the Mosque of Córdoba.

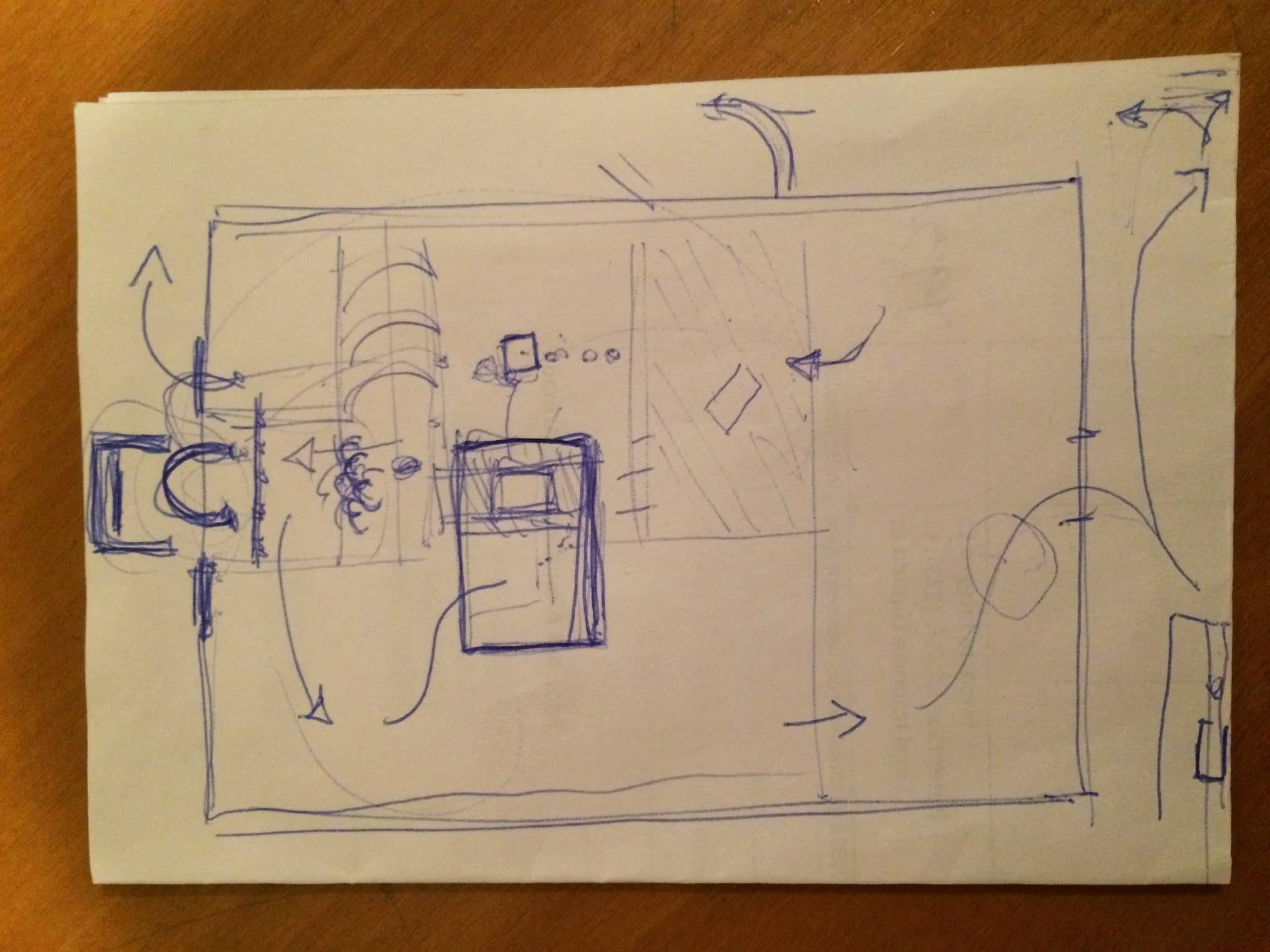

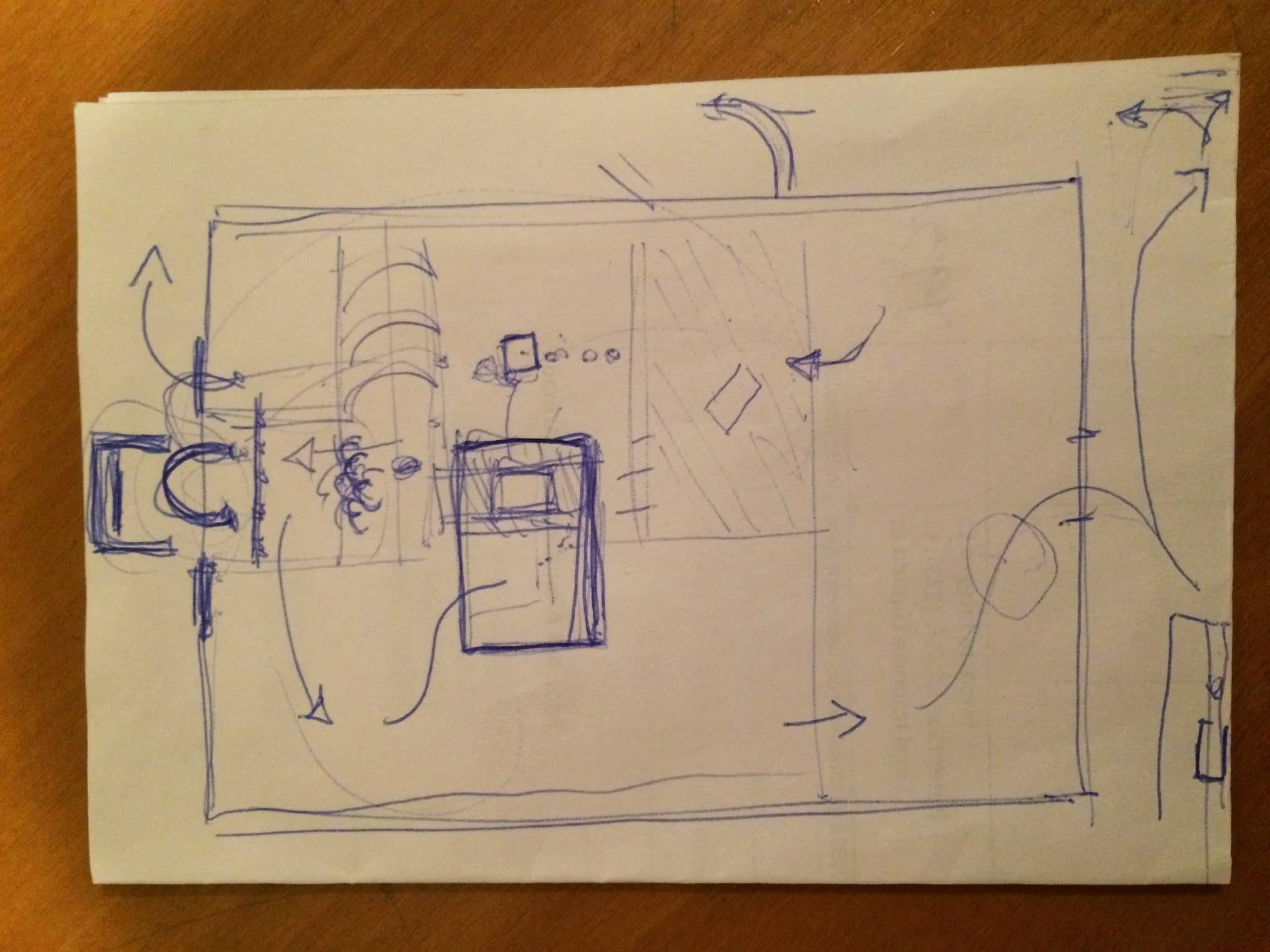

And finally, my favorite piece of paper ephemera: The Great Mosque is the first place I took students on a big trip in Spain, and this is a map from that visit, drawn for me by the colleague I was traveling with, of a suggested path through the mosque. So this is a modern, erm, signification of the space.

Some views of the Great Mosque of Córdoba, a building that is all modern significance, and always has been. At the moment it was built it signified an attempt to unify a fragmented Muslim community that included military rulers who had been left to do their own thing until the center of power moved west in the middle of the 8th century. It came to symbolize Córdoba during the period of the Umayyad emirate and caliphate, when it became the visual touchstone for al-Andalus (about which the art historian Susana Calvo Capilla has written —

Some views of the Great Mosque of Córdoba, a building that is all modern significance, and always has been. At the moment it was built it signified an attempt to unify a fragmented Muslim community that included military rulers who had been left to do their own thing until the center of power moved west in the middle of the 8th century. It came to symbolize Córdoba during the period of the Umayyad emirate and caliphate, when it became the visual touchstone for al-Andalus (about which the art historian Susana Calvo Capilla has written —