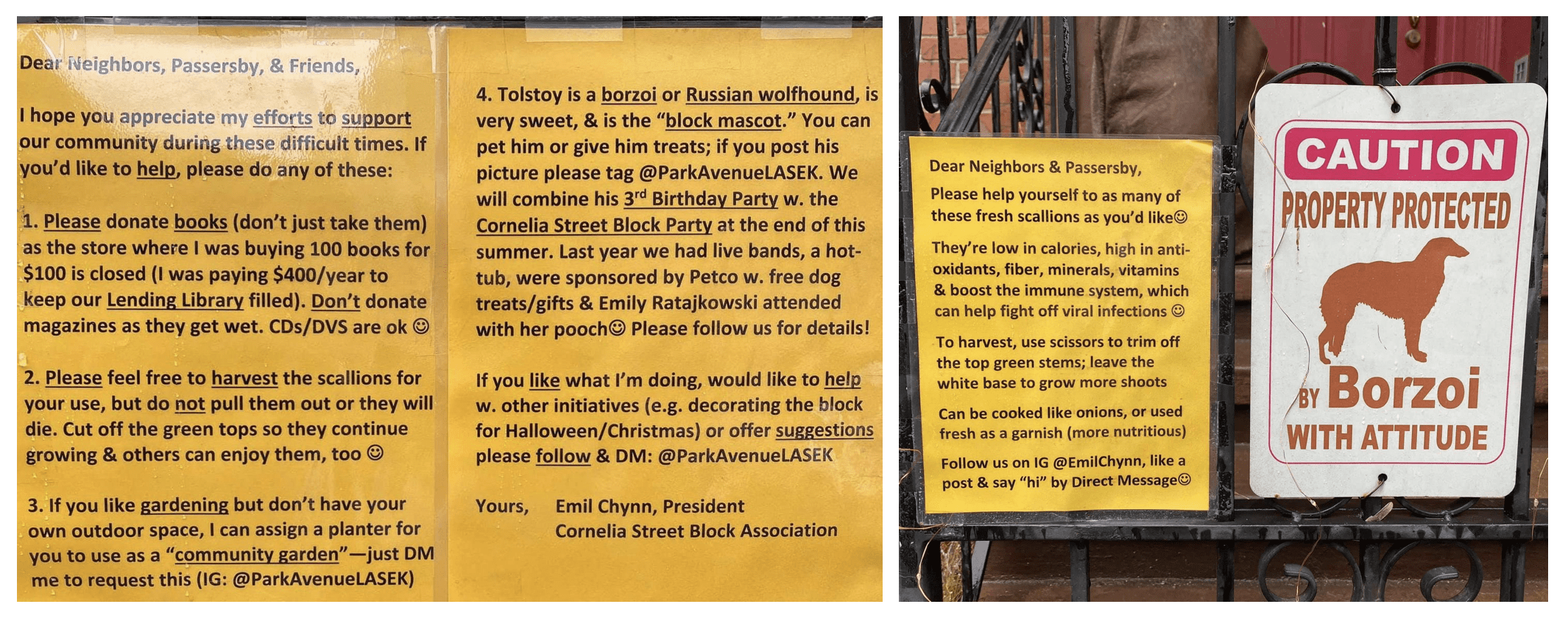

We mostly don’t have little free libraries in Manhattan, at least not downtown, but I came across one yesterday that has evidently been hit hard by the lockdown. It has a pretty big personality, plus onion chives.

We mostly don’t have little free libraries in Manhattan, at least not downtown, but I came across one yesterday that has evidently been hit hard by the lockdown. It has a pretty big personality, plus onion chives.

This is the point at which I got stuck on the Lone Medievalist Challenge. I’m actually writing this on August 27, but will backdate it so that it comes in the correct place in the order of my blog posts. The trouble that I was running into was in that I don’t know that “people of color” is a suitable term to use in the context of medieval Spain; and my explanations were falling short and the images I was choosing to shoehorn into the theme weren’t really doing what I needed them to do in able to facilitate a a post appropriately thoughtful for the subject. So: I’m not in any way saying, as some medievalists do and as my colleagues who work on the subject of race and race-making in the Middle Ages rightly decry, that race wasn’t an applicable category in the medieval period. Rather, what I’m saying is that “people of color” as a term seems to me so bounded by modern, western notions of race that to try to identify a “person of color” in medieval Spain requires, itself, a lot of racial categorization that I don’t think is appropriate for the scholar to take on.

With that said, I’m going to combine my “people of color” post with my “library/collection” post because the former allows me to talk about the latter in the context of modern medievalism.

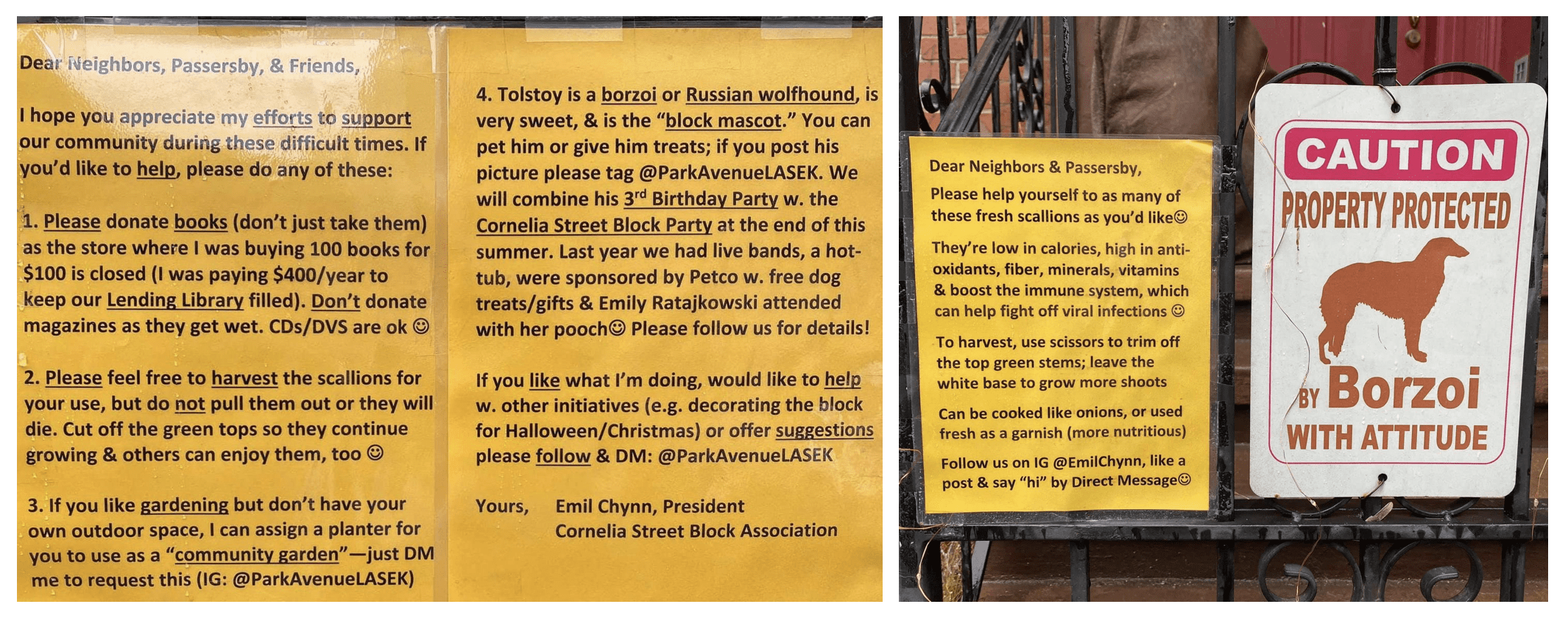

These are some images from the Beit-Bialik house-museum archive, where I spent several weeks last summer looking at Hayim Nahman Bialik’s manuscript draft of his Hebrew translation of Don Quixote and his notes from the time when he was editing the poetic diwan of Solomon ibn Gabirol. But in spite of Bialik’s interest in both the Jews of Spain and utilizing Spanish literature as a way of creating a world literature in Hebrew, he was largely contemptuous of actual Sephardim and Mizrahi Jews. There are two versions of a statement attributed to him, one saying that he hated Sephardim because they reminded him of Arabs and the other asking how he could hate Arabs when they were so like Sephardim; neither version reflects an attitude friendly toward people of color within the Jewish world or the Levant. The archivist of Beit-Bialik sees himself as an absolute defender of Bialik’s reputation; but reading work of scholars like Lital Levi and Sami Chetrit suggests that such a full-throated defense is not warranted.

I had the great good fortune last week to be able to sit with some of the treasures from the Valmadonna Trust library before they were sold off at Sotheby’s last week. There was no crowd there on a Friday afternoon, and I’ve gotten to know one of their Judaic people, who seems very happy to let scholars look at the books that are being sold before they potentially disappear onto a collector’s mantle-piece on Park Avenue or into his vault in London.

I’ve been looking back at some of the media coverage when it was first announced several years ago that the collection was going to be broken up and sold, as a last resort, after no buyer could be found for the entire collection. The Times’ Edward Rothstein made note of some of the quotations that were written on the walls of the exhibition space then, including: “Make books your companions. Let your bookshelves be your gardens,” which Rothstein identifies as “the words of a 12th-century Spanish Jewish scholar, Judah Ibn Tibbon, translated on one gallery wall.”

The epigram is taken from a lengthy letter written by Judah ibn Tibbon to his son, which survives in a single manuscript copy in Oxford:

That is a correct attribution as far as it goes, but there is much more to that quotation, how it ended up at the tip of Judah ibn Tibbon’s pen, and what he omitted in the process of transposing it from his native Spain to the France where he would spend most of his life in exile.