One of the ways that organizations have tried to maintain some kind of social connection during the shelter-in-place order is by creating Zoom book clubs. This is it!, I thought to myself. I can finally socialize in a way that is based around something I’m comfortable doing — reading!

But going to a book club as an academic is hard. I analyze text for a living. I read for a living. I ask questions about what I’m reading and explain it to people for a living. And all of those facts of my life mean that it would be very easy for me to dominate a conversation about books and talk over people’s heads. It’s not that I’m necessarily smarter, just that I have the tools to do this kind of thing a little bit more refined and in a little bit more regular use than most people. I make it a goal to blend in, but it doesn’t usually work. Even before the shelter-in-place order, I attended a book club meeting in person at a local bookstore. I shared at thought about the structure of that month’s novel, a thought I considered to be totally innocuous. I guess it wasn’t. Everyone was blown away by my insight (imagine me rolling my eyes here as I retell the story), and I had blown my cover.

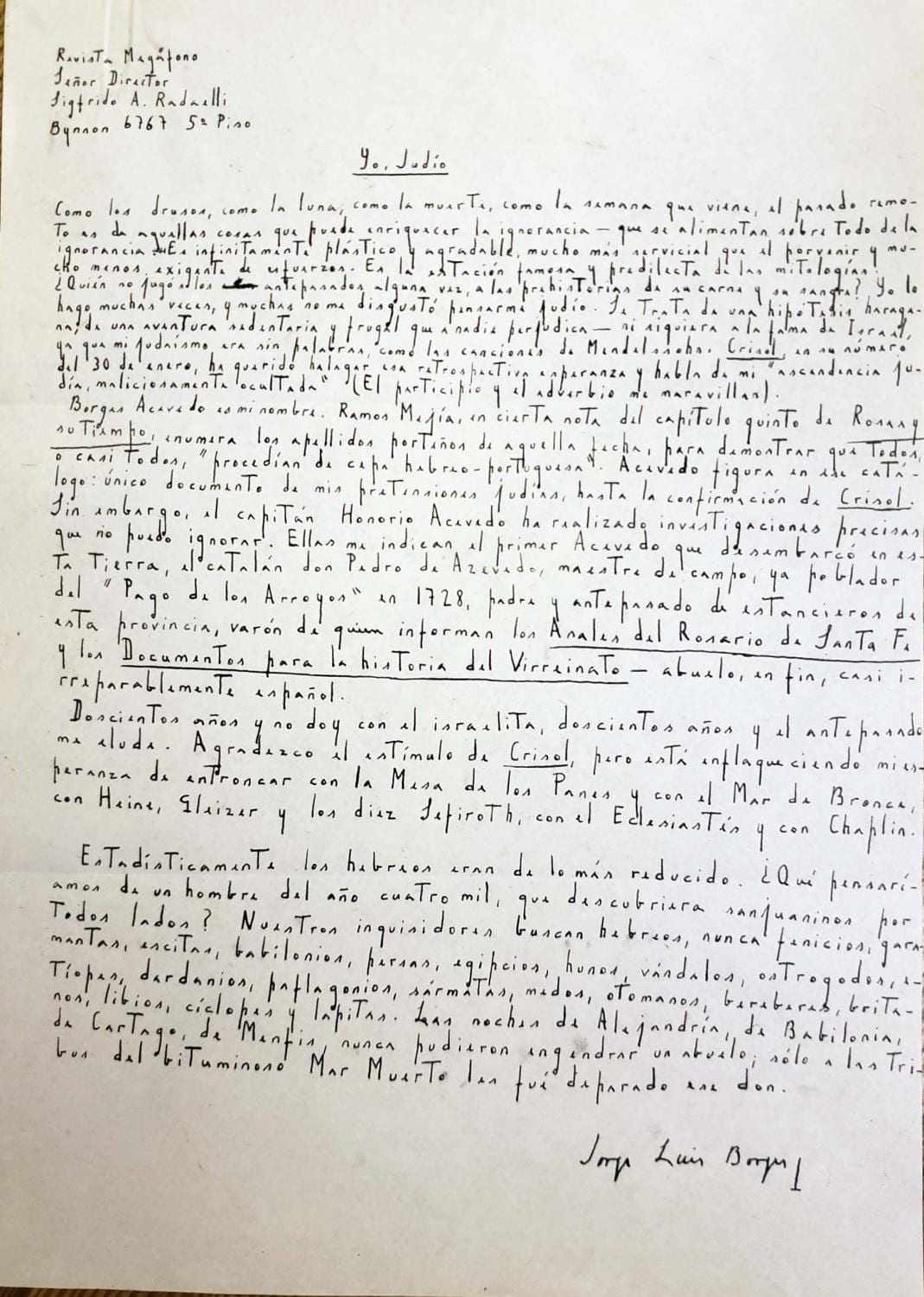

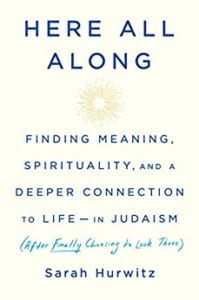

This week I tried a Jewish book club for people in their 20s and 30s, run by the synagogue I’m thinking about joining. Even though I found the book to be hopelessly superficial, I was resolved to behave myself like a civilian and try blend in. But my eyebrows betrayed me when one of the women in the group, during a conversation about lashon hara as discussed in the group’s book, said that she knew it was a solidly Jewish value because she hadn’t met any Jewish religious leaders who would ever engage in the practice. When the rabbi insisted that I verbalize what my eyebrows were already evidently saying by jumping about six inches above the top of my head (they do that of their own accord — traitors!), I said, “Well, it’s just that I was thinking about Ovadiah Yosef…” The woman looked kind of embarrassed. I felt terrible. I don’t think my eyebrows cared.

This exchange happened after a first one: The rabbi leading the group talked about imitatio dei being a Jewish value and I cringed. Apparently enough for it to be visible on Zoom. My overactive eyebrows are fairly substantial and therefore hard to miss when they jump up my face, even on a tiny screen and across a bad internet connection. The rabbi asked why I reacted so strongly to that, and I said that it just seemed like a very Christian way of formulating things. He insisted that it isn’t, that a phrase at the beginning of this week’s parsha — קְדֹשִׁ֣ים תִּהְי֑וּ כִּ֣י קָד֔וֹשׁ אֲנִ֖י יְהוָ֥ה אֱלֹהֵיכֶֽם׃ — is proof that imitatio dei is also a Jewish concept. We ultimately left it alone.

But I didn’t like it. The phrase, to me, evoked the idea of behaving in a god-like way within a salvific framework that is not operative in Judaism. So I did what any academic who has just been a total pain in the arse in a book club would do: I found a couple of articles and read them. Both are Jewish Studies-related and both use the phrase imitatio dei without comment. The second one I’ve linked to here, the one by Harvey, a noted historian of Judeo-Islamic philosophy, is published in an academic/Orthodox Jewish context, namely in the journal of the Rabbinical Council of America.

I realized that it was the very Latin-ness itself of the phrase that was what was bothering me, which is strange. Rationally and in every instant of my professional life I know very well that languages aren’t inherently confessional: Jews in the MENA speak Arabic, Arabic-speaking Christians use the word Allah to mean God when they pray, a large swath of the population in medieval Spain were native speakers of a Romance language, regardless of their faith tradition, etc. I’m often aware of the King Jamesiness of contemporary Jewish liturgies in English and it catches my attention, but ultimately I see it as an example of Anglophone Jews using the language that has evolved for us to talk to and about God.*

So what to make of this reflexive jolt of Latin = Christianity? It was valuable for me to read and react to things that I think about a lot professionally, but as a completely non-academic reader who wasn’t expecting much out of the book or the discussion. My low expectations let me just react without thinking about it, because I wasn’t expecting to be thinking about anything. I don’t know that we can ever deliberate sit down and try to read like a civilian, but there is something to be said for being surprised into it or by it. Reading reflexively is reminder of something that sometimes gets lost in textual criticism: that pure reaction is a part of reading that provides another path by which to seek meaning in a text.

All the same, I’d like the lockdown to be over soon. I think I prefer my old, familiar ways of being terrible at socializing. And honestly, a social life conducted entirely the internet has been pretty rough for my eyebrows.

*I have a review essay forthcoming in which I discuss the use of phrases from the KJV to describe medieval Jewish communities in contemporary English-language scholarship. I’m critical of it there, but to me there’s something different about Jewish liturgists making a deliberate, intellectual choice to integrate through theologically non-problematic words and phrases and non-Jewish academics imposing theologically very problematic words and phrases on their Jewish subjects. I mention this here because I’m expecting a lot of criticism for the review essay and I don’t want inconsistency on this position to create extra room for more; the two contexts are quite different.