(Or, How To Think Like a Literary Terrorist)

It is with absolute glee that I have returned to the literary translation project that I had to shelve 18 months ago in the interest of finishing my work and doing the kind of work that would count towards making me tenurable. Yes, I still have a bee in my bonnet about peer review and about what “counts,” but let’s shelve that for the moment in the interest of talking about a strange new nexus between literature and terrorism.

In the course of yesterday’s work, I arrived at a passage that discusses the Umayyad practice of crucifying convicts and the fear and displeasure it could inspire in the citizens of the capital city of Córdoba:

The promenade stretched out at the foot of the wall on the right bank of the river, unspooling a thread of fortresses and, sometimes, of crosses; for that is where the bodies of executed convicts were placed on public display. Amongst the smells of Córdoba that texts have preserved for us, one we have to overcome is the stench of rotting human flesh. Not for nothing does Ibn Khaldun (who knew everything) affirm that in the cities the air is cut with the putrid breath of filth and only thanks to the constant movement of people do waves of fresh air disperse those immovable humors.”

And because this is work for a general audience of readers, and because Islamophobic crimes and terrorist attacks have risen by order’s of magnitude since last year‘s presidential election, I found myself pausing to wonder how some general readers might misapprehend or misappropriate this graphic, smelly passage.

The white nationalists, Klansmen, neo-Nazis, sons of the Confederacy, and general racists, Islamophobes, and anti-Semites who have been dominating the news more and more (no, really, in spite of Trump having ruined that phrase for us, too) have shown themselves beyond willing to use the Middle Ages and classical antiquity to further their claims of religious hegemony and racial superiority. (For examples, see recent public interventions by my colleagues here, here, here, here, here, and here.) Their rhetoric is confused. On the one hand they use the term “medieval” to mean backwards and to criticize Islam. But on the other hand, they idealize the medieval as a time of racial purity. Crusading rhetoric has become commonplace in current political discourse. The Middle Ages is fair game for the racists who have proven themselves, over and over again, a hundred years ago and today, willing to kill for their cause.

One of the terrible things about terrorism is that you have to start to think like a terrorist just to go about daily life: When I pack to go to the airport, I have to think about whether anything I’m packing might be or look like something I could hijack or crash or blow up a plane with just to be able to get through security. I have to think about the most logical path for a gunman through a building to be able to have an escape-or-barricade plan in mind just in case, to be able protect myself day to day. I wouldn’t think about how to crash planes or shoot people in buildings otherwise but for the rise of terrorism and my need to go on with my life around it and around the security (theater) measures it has necessitated. Terrorism breeds terroristic thinking.

And now — do I have to think like an Islamophobe or a white supremacist just to be able to do my work and do no harm? I must take into account how my translation project about medieval Islam might be used against modern, flesh-and-blood Muslims by white nationalist terrorists. I have to wonder whether the above passage might be seized out of the historical and narrative context of late antique and early Islamic crucifixion and out of the context of the love letter to Córdoba that I am translating and used instead to demonize any and all Muslims, medieval and modern, as… I don’t know. I don’t want to have to get seven feet ahead of deadly hatred by imagining hatred. I don’t want to be the one who demonizes my academic subjects and my friends, even if it is to protect them. These are lines I will not cross.

I find myself in a quandary: If I go ahead with this project, if I put this paragraph out in the world, I might be putting ammunition into the hands of terrorists. But if I quash it, I let those same terrorists dictate nothing less than the very course of history, medieval and modern; they would limit what people could know about the Middle Ages and limit what people in the present could say about it.

I will confess an unpopular opinion here: I am a free-speech absolutist. Incitement to violence? No way. But short of that? Sure. Even after this weekend I’m still the Jew who believes that Nazis should be allowed to march down Main St. and that I should then denounce them long and loud. I believe that we fight speech with speech. It’s a position that has been sullied lately by white dudebros who don’t really understand or believe in free speech, but rather who feel entitled, but it is one that is still carefully thought and actively defended by organizations such as the ACLU. (This Twitter thread by my colleague David Perry is a useful and clear articulation of the difference and the consequences.)

This is not a decision I take lightly or unaware of the potential real-world consequences. But I will translate, I will publish, and if it all goes badly wrong I will fight speech with speech and hope that it will be enough.

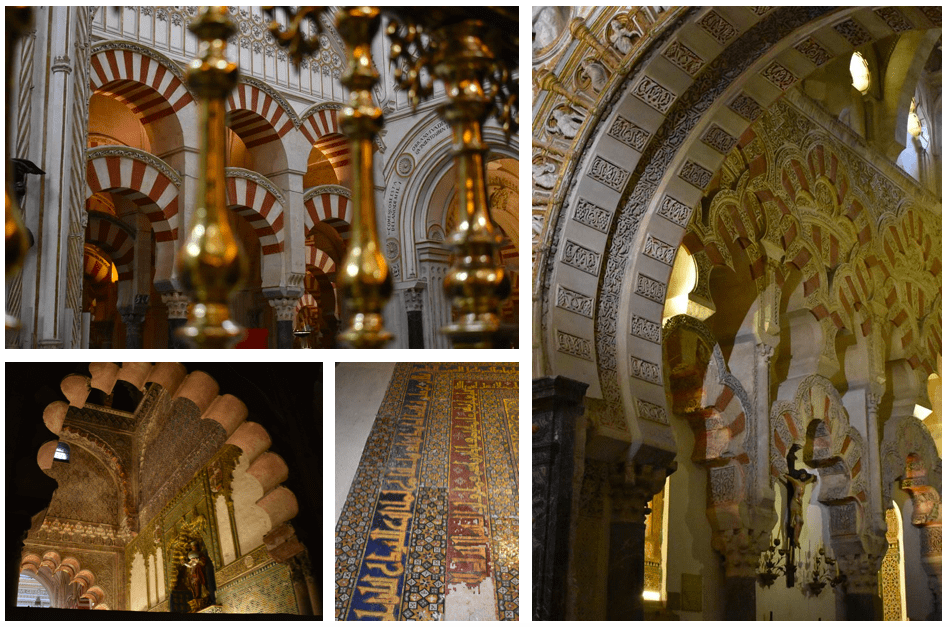

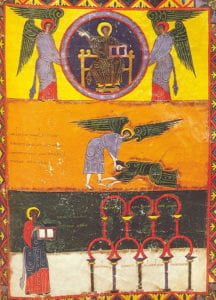

Some views of the Great Mosque of Córdoba, a building that is all modern significance, and always has been. At the moment it was built it signified an attempt to unify a fragmented Muslim community that included military rulers who had been left to do their own thing until the center of power moved west in the middle of the 8th century. It came to symbolize Córdoba during the period of the Umayyad emirate and caliphate, when it became the visual touchstone for al-Andalus (about which the art historian Susana Calvo Capilla has written — Las mesquitas de al-Andalus — and which is quite self-evident in the illuminations of the Beatus commentary on the apocalypse). When Fernando III took the city of Córdoba in 1236, the building was converted into church and left, architecturally, just as it always had been because it was the modern look for buildings of all sorts. When modern aesthetics turned to the Europeanizing and the baroque, Charles V plunked a baroque cathedral down in the center of the building.

Some views of the Great Mosque of Córdoba, a building that is all modern significance, and always has been. At the moment it was built it signified an attempt to unify a fragmented Muslim community that included military rulers who had been left to do their own thing until the center of power moved west in the middle of the 8th century. It came to symbolize Córdoba during the period of the Umayyad emirate and caliphate, when it became the visual touchstone for al-Andalus (about which the art historian Susana Calvo Capilla has written — Las mesquitas de al-Andalus — and which is quite self-evident in the illuminations of the Beatus commentary on the apocalypse). When Fernando III took the city of Córdoba in 1236, the building was converted into church and left, architecturally, just as it always had been because it was the modern look for buildings of all sorts. When modern aesthetics turned to the Europeanizing and the baroque, Charles V plunked a baroque cathedral down in the center of the building.