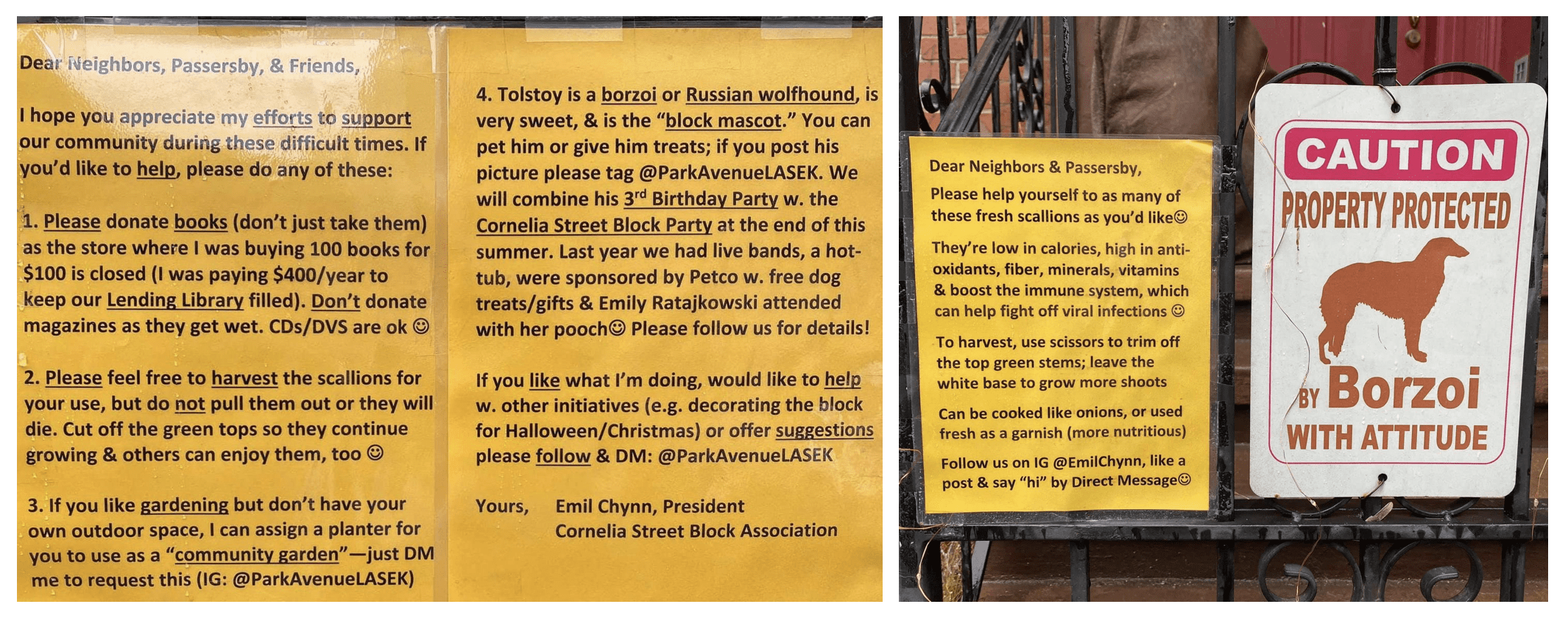

We mostly don’t have little free libraries in Manhattan, at least not downtown, but I came across one yesterday that has evidently been hit hard by the lockdown. It has a pretty big personality, plus onion chives.

We mostly don’t have little free libraries in Manhattan, at least not downtown, but I came across one yesterday that has evidently been hit hard by the lockdown. It has a pretty big personality, plus onion chives.

One of the ways that organizations have tried to maintain some kind of social connection during the shelter-in-place order is by creating Zoom book clubs. This is it!, I thought to myself. I can finally socialize in a way that is based around something I’m comfortable doing — reading!

But going to a book club as an academic is hard. I analyze text for a living. I read for a living. I ask questions about what I’m reading and explain it to people for a living. And all of those facts of my life mean that it would be very easy for me to dominate a conversation about books and talk over people’s heads. It’s not that I’m necessarily smarter, just that I have the tools to do this kind of thing a little bit more refined and in a little bit more regular use than most people. I make it a goal to blend in, but it doesn’t usually work. Even before the shelter-in-place order, I attended a book club meeting in person at a local bookstore. I shared at thought about the structure of that month’s novel, a thought I considered to be totally innocuous. I guess it wasn’t. Everyone was blown away by my insight (imagine me rolling my eyes here as I retell the story), and I had blown my cover.

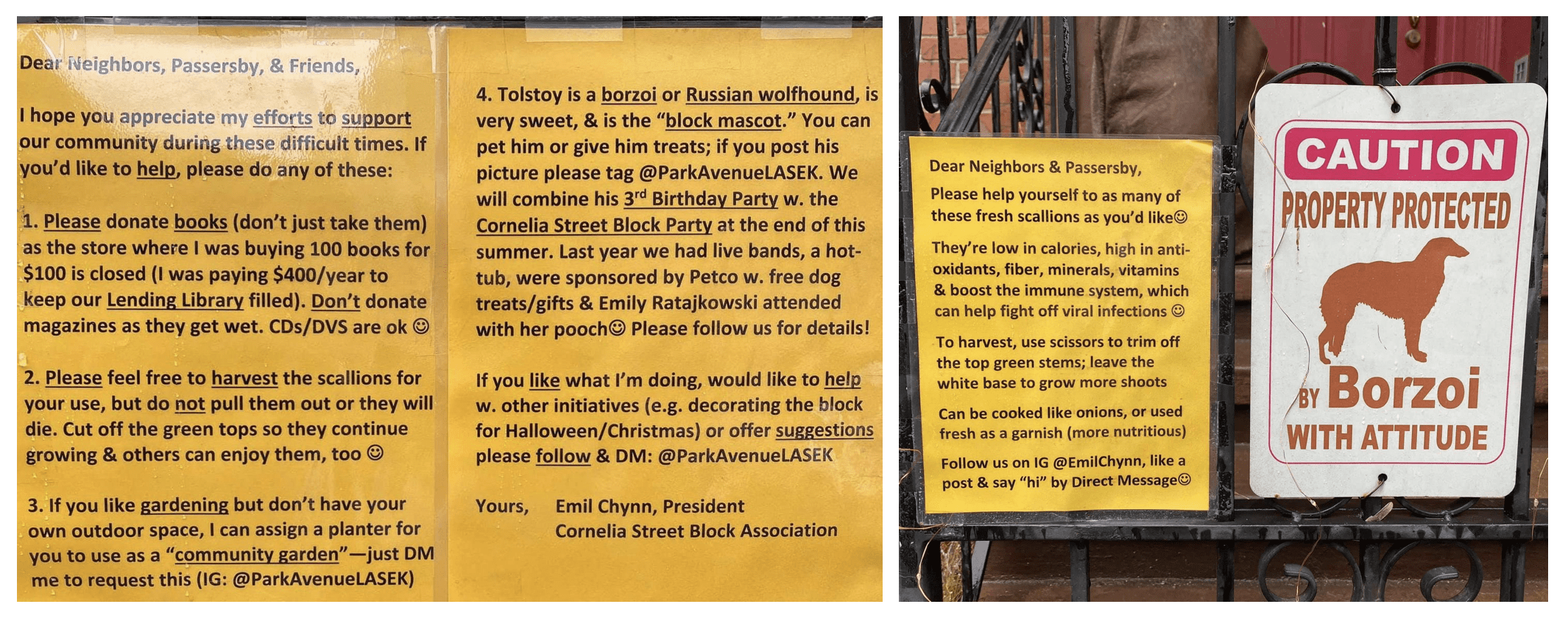

This week I tried a Jewish book club for people in their 20s and 30s, run by the synagogue I’m thinking about joining. Even though I found the book to be hopelessly superficial, I was resolved to behave myself like a civilian and try blend in. But my eyebrows betrayed me when one of the women in the group, during a conversation about lashon hara as discussed in the group’s book, said that she knew it was a solidly Jewish value because she hadn’t met any Jewish religious leaders who would ever engage in the practice. When the rabbi insisted that I verbalize what my eyebrows were already evidently saying by jumping about six inches above the top of my head (they do that of their own accord — traitors!), I said, “Well, it’s just that I was thinking about Ovadiah Yosef…” The woman looked kind of embarrassed. I felt terrible. I don’t think my eyebrows cared.

This exchange happened after a first one: The rabbi leading the group talked about imitatio dei being a Jewish value and I cringed. Apparently enough for it to be visible on Zoom. My overactive eyebrows are fairly substantial and therefore hard to miss when they jump up my face, even on a tiny screen and across a bad internet connection. The rabbi asked why I reacted so strongly to that, and I said that it just seemed like a very Christian way of formulating things. He insisted that it isn’t, that a phrase at the beginning of this week’s parsha — קְדֹשִׁ֣ים תִּהְי֑וּ כִּ֣י קָד֔וֹשׁ אֲנִ֖י יְהוָ֥ה אֱלֹהֵיכֶֽם׃ — is proof that imitatio dei is also a Jewish concept. We ultimately left it alone.

But I didn’t like it. The phrase, to me, evoked the idea of behaving in a god-like way within a salvific framework that is not operative in Judaism. So I did what any academic who has just been a total pain in the arse in a book club would do: I found a couple of articles and read them. Both are Jewish Studies-related and both use the phrase imitatio dei without comment. The second one I’ve linked to here, the one by Harvey, a noted historian of Judeo-Islamic philosophy, is published in an academic/Orthodox Jewish context, namely in the journal of the Rabbinical Council of America.

I realized that it was the very Latin-ness itself of the phrase that was what was bothering me, which is strange. Rationally and in every instant of my professional life I know very well that languages aren’t inherently confessional: Jews in the MENA speak Arabic, Arabic-speaking Christians use the word Allah to mean God when they pray, a large swath of the population in medieval Spain were native speakers of a Romance language, regardless of their faith tradition, etc. I’m often aware of the King Jamesiness of contemporary Jewish liturgies in English and it catches my attention, but ultimately I see it as an example of Anglophone Jews using the language that has evolved for us to talk to and about God.*

So what to make of this reflexive jolt of Latin = Christianity? It was valuable for me to read and react to things that I think about a lot professionally, but as a completely non-academic reader who wasn’t expecting much out of the book or the discussion. My low expectations let me just react without thinking about it, because I wasn’t expecting to be thinking about anything. I don’t know that we can ever deliberate sit down and try to read like a civilian, but there is something to be said for being surprised into it or by it. Reading reflexively is reminder of something that sometimes gets lost in textual criticism: that pure reaction is a part of reading that provides another path by which to seek meaning in a text.

All the same, I’d like the lockdown to be over soon. I think I prefer my old, familiar ways of being terrible at socializing. And honestly, a social life conducted entirely the internet has been pretty rough for my eyebrows.

*I have a review essay forthcoming in which I discuss the use of phrases from the KJV to describe medieval Jewish communities in contemporary English-language scholarship. I’m critical of it there, but to me there’s something different about Jewish liturgists making a deliberate, intellectual choice to integrate through theologically non-problematic words and phrases and non-Jewish academics imposing theologically very problematic words and phrases on their Jewish subjects. I mention this here because I’m expecting a lot of criticism for the review essay and I don’t want inconsistency on this position to create extra room for more; the two contexts are quite different.

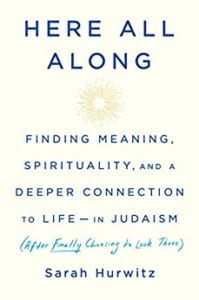

Just something simple but pretty to look at in bad times. Dust jacket of a 1951 translation of a talk given by Bialik in 1913, when he was still based in Odessa. It’s pink Italian paper laid out on a screen mold; “PMF Italia” is watermarked on the opposite corner.

Disability studies is another area where I really don’t work at all. This is a book that has been on my to-read list for a long time; I should really get on it.

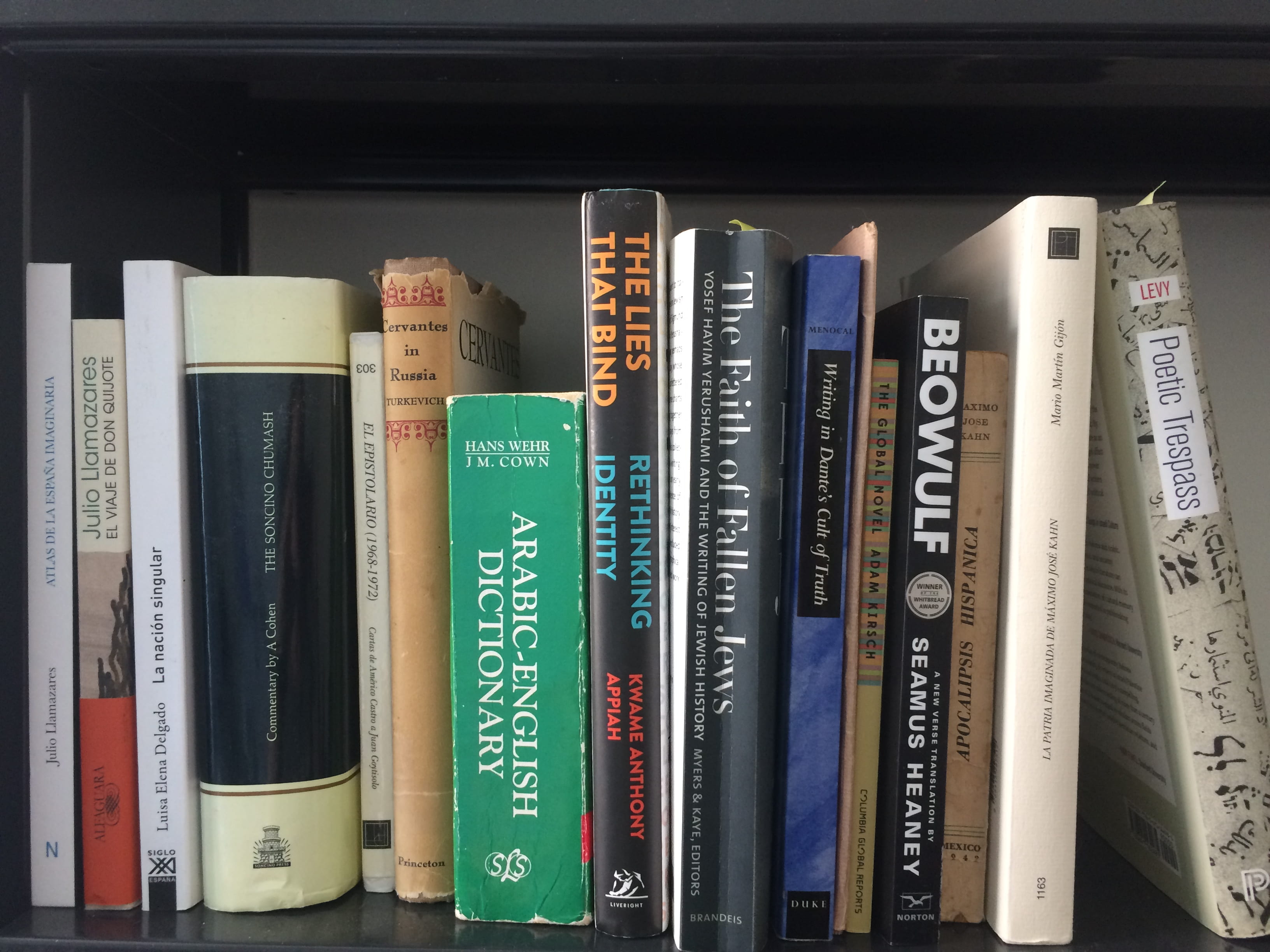

I’m moving this week, so I can best show my current interest with the few books that I left unpacked to work on the introduction to my current book project and the chapter that I’m currently writing. The book is a reception history, examining the ways in which medieval poetry and poets from al-Andalus are implicated in various nationalist discourses of the 20th century. I’m reading and writing about different modes of constructing national identity and how different facets of it (language, religion, race, geography, etc.) function for the various nationalist writers whose work I am analyzing.

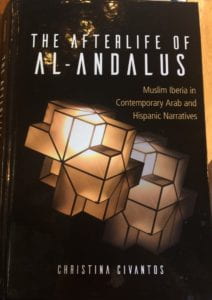

The book that I’m actively reading is Christina Civantos’ The Afterlife of al-Andalus (SUNY Press, 2017), which looks at traces of Andalusi literature in Argentine and Palestinian writing. I’m finding it to be an engaging book because I don’t understand the medieval history in the same way that Civantos does in order to set up the foundations from which she can carry out a postcolonial analysis of post-Andalusi literary works. And so it’s challenging me to more carefully articulate how I’m thinking about empire and governance in medieval Spain and its consequences in the modern world for the introduction to my own book.

And for non-academic (but not totally unrelated) purposes, I’m reading The Making Of, which is a series of interviews with the key players who were involved in the renovation of the Royal Museum for Central Africa, just outside of Brussels, which I visited last month. It’s funny how reading sometimes, completely coincidentally, groups thematically: I’m doing a lot of reading in postcolonial theory at the moment, both in and out of my academic life.

Best passing material-book/scribal culture remark: “‘I can read the first few lines and these in the middle of the second page, and one or two at the end. Those are as clear as print,’ said he, ‘but the writing in between is very bad, and there are three places where I cannot read it at all.'” — “The Adventure of the Norwood Builder,” Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, The Complete Sherlock Holmes

Fictional shacks that are larger than my bedroom: Black Peter’s cabin in “The Adventure of Black Peter,” Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, The Complete Sherlock Holmes

Something I’d like to go back and tally: The number of bicycles in the second half of The Complete Sherlock Holmes

Don’t ever tell me my line of work is too obscure if a prize-winning, best-selling novel can just casually quote the Mozarab jarchas: Señales de humo by Rafael Reig

Of course a literary manual for cannibals is going to be a two-parter: La cadena trófica also by Rafael Reig

Madrid books: See above — they’ve got a super sense of place.

Italy books: Venice: Pure City by Peter Ackroyd; Venice, an Interior by Javier Marías (which was originally a longish newspaper essay and was only ever published in chapbook form in English and Italian translations); Day after Day by Carlo Lucarelli, translated by Una Stransky, audiobook read by Daniel Philpott

Cambridge/Granchester book: Sidney Chambers and the Shadow of Death by James Runcie

Israel books: The Mandelbaum Gate by Muriel Sparks; Someone to Run With by David Grossman; Volverse Palestina by Lina Meruane

(Bonus shocker of the year: Nick Hornby was totally right about Muriel Sparks!)

More Cuba books, because I am still haunted: Caviar with Rum, eds. Jacqueline Loss and José Manuel Prieto; Cuba in the Special Period, ed. Ariana Hernández Reguant; Dreaming in Russian by Jacqueline Loss

Michigan books: All-American Yemeni Girls by Loukia Sarroub

Because moving to Ann Arbor marked the first time I had to wrangle my cat onto an airplane: Catwings by Ursula K. LeGuin

Thought I would be okay taking these books on a trip and leaving them behind but definitely wasn’t: The Cooking Gene by Michael Twitty; The Library Book by Susan Orlean

Thought I would be okay taking these books on a trip and leaving them behind but definitely wasn’t: The Cooking Gene by Michael Twitty; The Library Book by Susan Orlean

Was completely fine leaving this on the airplane when I finished it: Kitchens of the Great Midwest by J. Ryan Stradal

Have we met?: The Pedant in the Kitchen by Julian Barnes

Hit too close to home to finish: Iphigenia in Forest Hills by Janet Malcolm

Much too much to distill into one pithy comment: Barracoon by Zora Neale Hurston

Best babushka: Ali’s Russian mother in Ali and His Russian Mother by Alexandra Chetriteh, translated by Michelle Hartman

Ironically, didn’t tell me much I didn’t already know: The Death of Expertise by Tom Nichols

And perhaps less ironically, White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo, which seems to have been written for people who just haven’t been paying any attention at all

Ironically, written at a pace that made me more anxious: Notes on a Nervous Planet by Matt Haig

Because apparently being in a relationship means attempting to share in your partner’s interests, even when those interests are Melville: Billy Budd and Other Stories by Herman Melville

Because it’s hard to be patient when learning a language in which one has much better reading comprehension than ability to generate verbal forms: In Other Words by Jhumpa Lahiri

Because, 2018: Not All Dead White Men by Donna Zuckerberg; Infidel by Pornsak Pichenshote; Holocaust Tips for Kids by Shalom Auslander

***

2018 favorites: The Mandelbaum Gate, Billy Budd, Barracoon, The Library Book

***

I have a huge fantasy that I’ll read about six more books before the end of the year, but if it happens, those’ll have to go onto next year’s roundup because reading for pleasure shouldn’t have high-pressure deadlines. Happy reading, all!

This is a lightly edited version of the comments that I made following Eric Calderwood’s talk at the Colubmia Workshop “Sites of Religious Memory in an Age of Exodus: The Western Mediterranean.” Part of the reason I’m posting my response is precisely because it is dependent upon reading his new book, Colonial al-Andalus, which I want to encourage. There are many people in medieval studies — especially those who are convinced that there is only one correct way to care about race, nation, and colonialism’s impacts upon the field and that people who work on Spain and North Africa and their modern-medieval legacies Don’t Do It Right ™ or at all — who would benefit tremendously from it. It’s also just fabulous and fascinating. So, go read the book and then come back to this as a response to chapter 6:

This is a lightly edited version of the comments that I made following Eric Calderwood’s talk at the Colubmia Workshop “Sites of Religious Memory in an Age of Exodus: The Western Mediterranean.” Part of the reason I’m posting my response is precisely because it is dependent upon reading his new book, Colonial al-Andalus, which I want to encourage. There are many people in medieval studies — especially those who are convinced that there is only one correct way to care about race, nation, and colonialism’s impacts upon the field and that people who work on Spain and North Africa and their modern-medieval legacies Don’t Do It Right ™ or at all — who would benefit tremendously from it. It’s also just fabulous and fascinating. So, go read the book and then come back to this as a response to chapter 6:

***

Speaking in New York City about the use of al-Andalus as a site of memory in the creation of both a colonial and later an independent Morocco mediated by the visual vernacular of its architecture, it is almost impossible to avoid thinking about the reinstallation of the Islamic galleries at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the especially the creation of the Moroccan Court in 2011 and the ways in which the museum presented and justified the project. For those who don’t know the background: following upon the last major overhaul of its Islamic galleries in the 1970s which showed a real drive, innovative at the time, toward displaying Islamic art not as craft but as art on a par with the European objects in the collection, the Met, in the 8-year reimagining of the galleries culminating in 2011, moved its presentation of the artworks more towards accessibility, relevance, and cultural-historical contextualization. One of the centerpieces was the creation, de novo, of a Moroccan courtyard by Moroccan artists, designers, and craftsmen, with consultation from curators and architectural/landscape historians on staff at the museum. This followed the museum’s precedent of the creation of a Ming Dynasty-style garden court when the East Asia galleries where revamped in the early 1980s.

A mini-documentary on the museum’s web site records some of the processes of creation; and in rewatching it after reading Eric’s chapter, what really jumped out was the way in which the curatorial thinking about what constitutes Moroccan architecture was very much informed by the Moroccan nationalist appropriation of the colonial/fascist discourse about being the site and the heritor and continuation of Andalusi cultural heritage.

To highlight some examples:

The New York-based echoes of the historical movement(s) that Eric has identified are fairly self-evident. This is al-Andalus mediated through Morocco, it is the Middle Ages mediated through Moroccan craftsmen, it is the elevation of the urban environment. But one theme that struck me both in Eric’s analysis of how this kind of narrative unfolded and the way in which it’s picked up by the Met staff was that of authenticity.

Three examples of where the idea of authenticity occurs in the chapter are:

What I want to do by highlighting these short citations and the same terminology that occurs when the Met curator talk about the Moroccan courtyard is to raise the question of how the different players on this stage understand the question of authenticity, the axes of authenticity, and of how that understanding is bequeathed, very implicitly, going forward. In other words, it’s not just a simple question of what authenticity means and then of what is authentic in terms of historicity and geography, but also of what a kind of joint Spanish-Moroccan authenticity might imply.

In the study of medieval Spain and North Africa, it has become increasingly clear, especially in the last 15-20 years to many practitioners that historical and literary scholarship need to see the Maghreb as an integral cultural unit rather than as two spaces divided by traditional Ango-American views of what constitutes nations in Europe and where a hard break between Europe and Africa occurs. But at the same time, what Eric has shown is the very pernicious side of that kind of unitary thinking. And so this raises two questions in moving forward: How do we account for this impulse in medieval scholarship? And to how we can look at the region in a unitary way without replicating the violence of the colonial project that was so contingent upon the very continuity that we are currently viewing as desirable and necessary?

***

Postscript: I left this final paragraph out of my comments at the workshop because I didn’t want to pull my remarks in too many different directions and because this was really ultimately more of a response to the status quo of #medievaltwitter than to anything that was happening in the conference — mercifully there is still a world of thought offline! — but this was another issue that came up in formulating my thoughts about the book.

I think that it’s worth mentioning that many areas of medieval studies are — very much to their benefit — beginning to appreciate this kind of historiographic work that clarifies where some of the modern understandings of places and cultures that are often attributed to the Middle Ages in fact come into being in the modern period. It’s in part a natural element of the field to know its own history, and in part it’s being accelerated by very contemporary repurposing of medieval tropes such as Crusades and Vikings on the extreme right to justify all kinds of contemptible, hateful modern attitudes. Medievalist responses have very much been drawn down black-and-white lines. Even as in my own historiographic research right now, I’m reading a book of poetry by Manuel Machado that is basically a paean to Franco that casts him as a medieval Christian reconquerer no less than Fernando el Católico or the Cid; and so while I knew that Franco had tried to be a bit sensitive about covering up figures of Santiago Matamoros when he met with his Moroccan generals, I was really surprised to learn about the extent of Francoist engagement with and promotion of Islam. It’s a historiography that doesn’t fall along the neat lines of other European historiographies, where the various fascist forces uniquely adopted the Christian Middle Ages to imagine their histories. With that said, I’ll just leave off with a final question: To what extent is this a case of “España es diferente” and to what extent should we see it as a call to reexamine the one-dimensional nature of the current discourse on the relationship between medievalism in general and mid-century fascism?

Normally I don’t include my academic reading in my year-end roundup, but I wanted to keep track of what I accomplished on my sabbatical so I have a running list already prepared. I didn’t end up reading exactly what I expected. I thought that I would sit and read a lot of Arabic text since I had time to work without interruption. However, I found that just coming off of finishing the book that has had me tied to my desk chair since 2011-12, I didn’t just didn’t want to sit at my desk. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to work or to read, but I wanted to not be in a desk chair at a desk. I read out of doors and, since the weather was mostly disgusting in the summer and then, suddenly, freezing, with very little in between, on my couch in my living room. The little table-sitting that I did was devoted to working on a translation project that is ongoing. I didn’t have the wherewithal for another semester of all-day desk-sitting, so I translated in the morning and read, took notes, and wrote while sitting on the couch in the afternoons. Like translating, reading medieval Arabic text is a desk activity, and so it just didn’t happen that much; it was one or the other in terms of desk time and I wanted to make some progress on that project, which had stalled while I finished my book. Realistically, I was also just mentally exhausted from finishing the book and tenure, and reading text is a taxing activity; certainly far moreso than reading scholarship. In a certain respect, keeping this list has gotten me to think about habits of reading and the physicality that governs them. I thought that the long stretch of time would be good for reading text, but it was actually better for reading scholarship precisely because of how I was prepared to sit or not sit after years of a very specific kind of sitting. I’m hoping that now that I’m back to teaching, where I’ll have blocks of time where I’m on my feet, blocks of time where I’m prepping classes (which I can do anywhere), and blocks of time in meetings — that is, I’ll have lots of different physical modes of being at work — that I’ll be able to put in an extra hour or two of desk time, both physically and mentally. (I’m also hoping this doesn’t sound completely bonkers.)

With that said, here’s the mostly-complete list of what I read this semester with an eye toward reading widely and starting to think about the intellectual setting and framework for my next book:

Altschul, Nadia and Kathleen Davis, ed. Medievalisms in the Postcolonial World: The Idea of “The Middle Ages” Outside Europe. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009.

Benor, Sarah Bunin. “Jewish English,” in A Handbook of Jewish Languages, ed. Lily Khan. Leiden: Brill, 2016. 130-7.

—. “Do American Jews Speak a ‘Jewish Language’?: A Model of Jewish Linguistic Distinctiveness,” Jewish Quarterly Review 99:2 (2009): 230-69.

Bishop, Chris. Medievalist Comics and the American Century. Jackson: The University Press of Mississippi, 2016.

Calderwood, Eric. “Franco’s Hajj: Moroccan Pilgrims, Spanish Fascism, and the Unexpected Journey of Modern Arabic Literature,” PMLA 135:5 (2017): 1097-1116.

Coope, Jessica. The Most Noble of People. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 2017.

Dangler, Jean. Edging Toward Iberia. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2017.

Derrida, Jacques. “Like the Sound of the Sea Deep Within a Shell: Paul de Man’s War,” Critical Inquiry 14:3 (1988): 590-652.

Dockray-Miller, Mary. Public Medievalism, Racism, and Suffrage in the American Women’s Colleges. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

Efron, John M. German Jewry and the Allure of the Sephardic. Princeton: UP, 2016.

—. “Scientific Racism and the Mystique of Sephardic Racial Superiority,” The Leo Baeck Institute Year Book 38:1 (1993): 75-96.

Guichard, Pierre. Los reinos de taifas: Fragmentación política y esplendor cultural. Málaga: Editorial Sarriá, 2005.

Hernández Cruz, Victor. In the Shadow of al-Andalus. Minneapolis: Coffee House Books, 2011.

Herman, David. “Narrative Worldmaking in Graphic Life Writing,” in Graphic Subjects: Critical Essays on Autobiography and Graphic Novels, ed. Michael Chaney. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2011. 231-43.

Hever, Hanan. Suddenly, the Sight of War. Stanford: UP, YEAR.

Horn, Dara. “The Future of Yiddish in English,” Jewish Quarterly Review 96 (2006): 471-80.

Judt, Tony. A Grand Illusion?: An Essay on Europe. New York: UP, 2011.

León, María Teresa. Doña Jimena Díaz de Vivar: Gran señora de todos los deberes. Madrid: Castalia, 2004 reprint.

—. La Historia tiene la palabra: Noticia sobre el salvamiento del Tesoro artístico de España. Madrid: Endymion, 2009.

Marx, Karl. “On the Jewish Question,” in The Early Writings. New York: Penguin.

Moretti, Franco. Distant Reading. New York: Verso Books, 2013.

Muñoz Molina, Antonio. Córdoba de los omeyas. Madrid: Seix Barral, 1991.

Nirenberg, David. Anti-Judaism.

Ozick, Cynthia. “America: Toward Yavneh,” in What is Jewish Literature?, ed. Hana Wirth-Nesher. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1994. 20-35.

Rashid, Hussein, “Truth, Justice, and the Spiritual Way: Imam Ali as Superhero,” in Muslim Superheroes: Comics, Islam, and Representation, ed. A. David Lewis and Martin Lund. Boston: Harvard University Press, 2017.

Ravitzky, Aviezer. The Roots of Kahanism: Consciousness and Political Reality. Jerusalem: The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1986.

REDACTED, Prof. Dr. REDACTED. REDACTED: A book I reviewed in manuscript, confidentially, for a press. REDACTED: REDACTED Press. Forthcoming, inshallah, 2018.

Rein, Raanan. “Echoes of the Spanish Civil War in Palestine: Zionists, Communists, and the Contemporary Press,” Journal of Contemporary History 43:1 (2008) 9-23.

Rennger, N.J. “The neo-medieval global polity,” in International Relations: Theory and the Politics of European Integration, ed. Morten Kelstrup and Michael Williams. New York: Routledge, 2000. 57-71.

Rodríguez, Ana A. “Mapping Islam in the Philippines: Moro Anxieties of the Spanish Empire in the Pacific,” in The Dialectics of Orientalism in Early Modern Europe, eds. Keller, Marcus and Javiero Irigoyen García. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017. 85-100.

Rosser-Owen. Maryam. Islamic Arts from Spain. London: V&A Publishing. YEAR?

Roth, Laurence. “Innovation and Orthodox Comic Books: The Case of Mahrwood Press,” Multi-Ethnic Literature of the United States 37:2 (2012): 131-56.

Salgado, Minoli. “The Politics of Palimpsest in The Moor’s Last Sigh,” in The Cambridge Companion to Salman Rushdie, ed. Abdulrazak Gurnah. Cambridge: UP, 2007. 153-68.

Schirmann, Jefim. “Samuel Hanagid: The Man, the Soldier, the Politician,” Jewish Social Studies 13:2 (1951): 99-126.

—. “The Wars of Samuel Ha-Nagid,” Zion

Schorsch, Ismar. “The Myth of Sephardic Supremacy,” The Leo Baeck Institute Yearbook 34:1 (1989): 47-66.

Stein, Sarah Abrevaya. “Sephardi and Middle Eastern Jewries Since 1492,” in The Oxford Handbook of Jewish Studies, ed. Martin Goodman, et al. Oxford: UP: 2002. ##.

Tabachnick, Steven E, ed. The Cambridge Companion to the Graphic Novel. Cambridge: UP, 2017.

—. The Quest for Jewish Belief and Identity in the Graphic Novel. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 2014.

El-Tayyib, Fatima. European Others: Queering Ethnicity in Postnational Europe. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011.

Unamuno, Miguel de. Gramática y glosario del Poema del Cid. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 1977.

Viguera Molins, María Jesús. “El Cid en las fuentes árabes,” in Actas del Congreso Internacional El Cid, Poema e Historia, ed. César Hernández Alonso. Burgos: Ayuntamineto de Burgos, 2000.

Wilson, G. Willow. “Machina ex Deus: Perennialism in Comics,” in Graven Images: Religion in Comic Books and Graphic Novels, ed. A. David Lewis. New York: Continuum Publishing, 2010. 249-56.

Zihri, Oumelbanine. “A Capitve Library Between Spain and Morocco,” in The Dialectics of Orientalism in Early Modern Europe, eds. Keller, Marcus and Javiero Irigoyen García. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017. 17-31

About two-thirds of the way through my lecture class meeting on Wednesday, one of the students shouted out, loudly enough for the whole room to hear: “THIS IS JUST LIKE LITERATURE DUNGEONS AND DRAGONS!” Not all of the students were quite that enthusiastic about the day’s activity, but most of them got into it and I think that the activity that I will be calling Literature Dungeons and Dragons from here on out (it is medieval, after all), was a success.

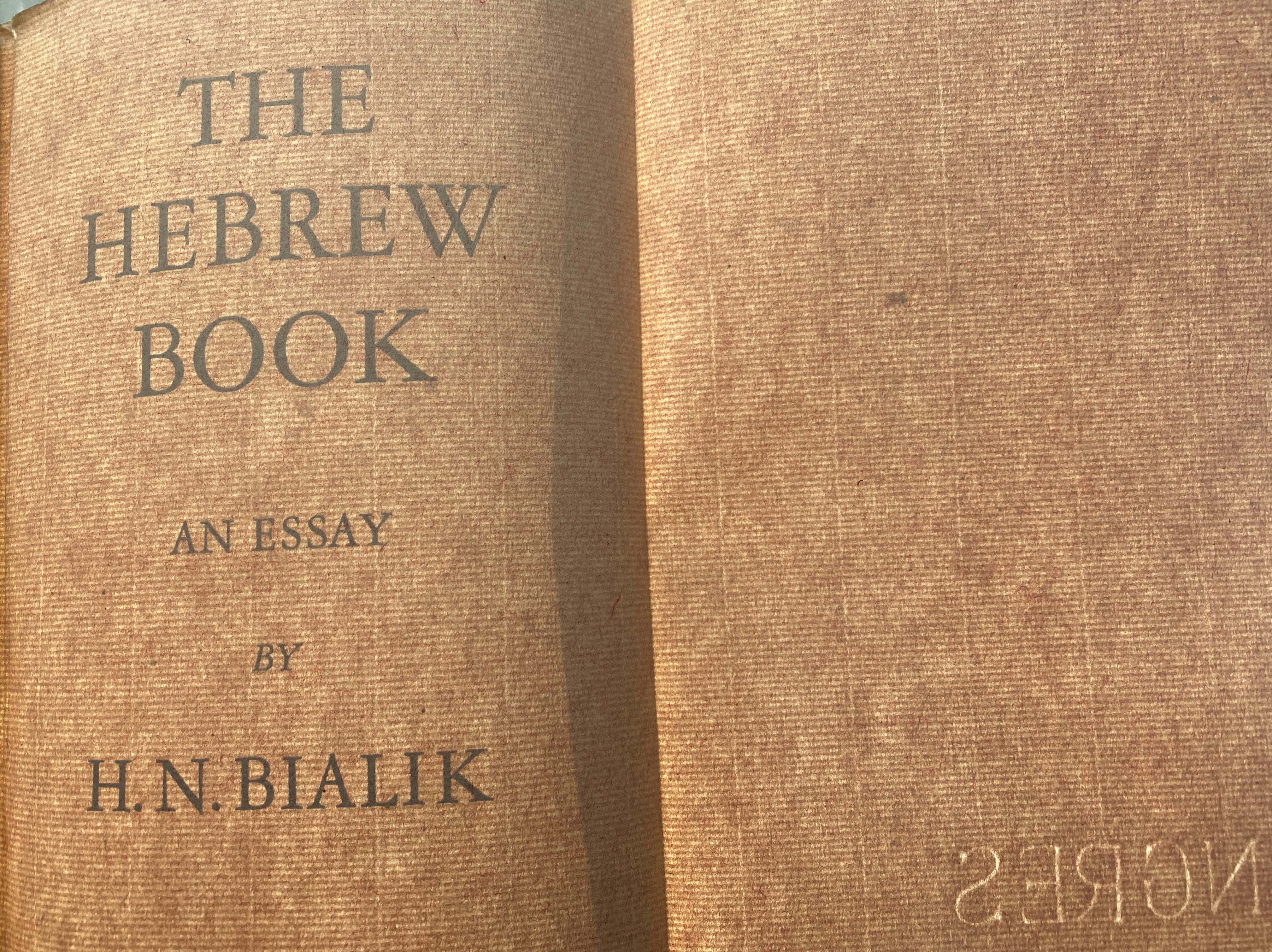

I had the great good fortune last week to be able to sit with some of the treasures from the Valmadonna Trust library before they were sold off at Sotheby’s last week. There was no crowd there on a Friday afternoon, and I’ve gotten to know one of their Judaic people, who seems very happy to let scholars look at the books that are being sold before they potentially disappear onto a collector’s mantle-piece on Park Avenue or into his vault in London.

I’ve been looking back at some of the media coverage when it was first announced several years ago that the collection was going to be broken up and sold, as a last resort, after no buyer could be found for the entire collection. The Times’ Edward Rothstein made note of some of the quotations that were written on the walls of the exhibition space then, including: “Make books your companions. Let your bookshelves be your gardens,” which Rothstein identifies as “the words of a 12th-century Spanish Jewish scholar, Judah Ibn Tibbon, translated on one gallery wall.”

The epigram is taken from a lengthy letter written by Judah ibn Tibbon to his son, which survives in a single manuscript copy in Oxford:

That is a correct attribution as far as it goes, but there is much more to that quotation, how it ended up at the tip of Judah ibn Tibbon’s pen, and what he omitted in the process of transposing it from his native Spain to the France where he would spend most of his life in exile.