On Monday, 150 of my students and colleagues were arrested on campus during a peaceful protest. This is the letter I wrote to the president and the provost in response:

Dear Linda and Gigi,

I am writing to you adjacent to the letter you will have received from a group of Jewish faculty members regarding recent events on campus. I am writing separately because I do not want to co-sign a letter that calls for BDS or the closure of the Tel Aviv study abroad site; however, in every other respect I am in agreement with the concerns outlined in the letter by those colleagues with whom I am in religious community.

As a matter of principle, I do not believe in cultural or academic boycotts. As a practical matter, I conduct research in archives and libraries in Israel and have fruitful collaborations with colleagues there, many of whom are among the fiercest critics of the Israeli government and its policies toward Palestinians and regarding other matters such as judicial transparency, religious pluralism, and gender equity. I consider myself fortunate to have spent time at NYU-Tel Aviv as part of the GRI. However, I do believe that the value of boycotts is a matter on which reasonable people can disagree and that students and faculty must not be inhibited from expressing their opinions, demanding change, and trying to persuade others of their perspective.

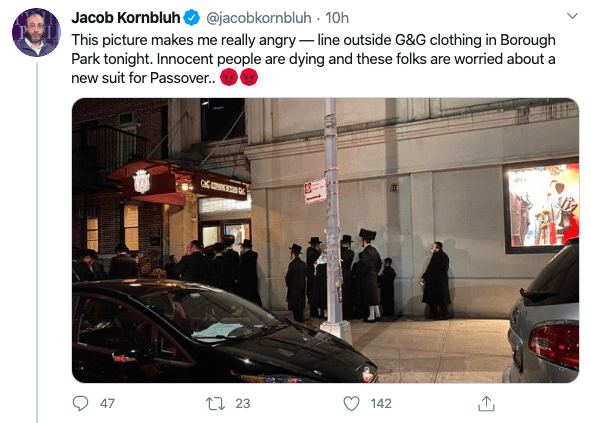

Like my colleagues who have already written to you, I am dismayed by the extent to which claims of antisemitism have been exaggerated and used to quash student and faculty expression. While I may not agree with the substance of much of the protest or the set of demands coming from the students who formed the encampment on Gould Plaza and while I may find some of their commentary, chanting, etc., to be disagreeable, in poor taste, incorrect, or objectionable, I have a difficult time construing those things as threats to me as an American Jew on an American university campus.

I have seen the national debate at large about US involvement in Israel and about Israeli policies use antisemitic tropes and trade at times in antisemitic ideas. However, by and large that has not been the case at NYU and I am grateful to my students and colleagues that we can disagree about a very serious political matter without our discussions taking that sinister turn. It is my own opinion that calls for the end of Israel as a Jewish state without similar calls for the end of other theocracies or countries with records of human rights violations may be questionable in their motivation and their impact. However, I can also recognize that many people, including many Jews, do not view it that way; and it is precisely because disagreement exists on this question that I could not imagine imposing my own perspective on this matter, foreclosing discussion entirely, or asking the university to do it in the name of protecting me and my peers.

Linda, we have only met a few times in the context of your previous role in Global and my involvement with programming at NYU-Madrid, but if I may address you directly as I close my letter: It meant a tremendous amount to me to see a Jewish woman appointed president of the university. There’s no real reason for it except that affinity is funny like that. Now, however, I am embarrassed and angry to see a coreligionist quashing debate, which is so central to the Jewish tradition, and, what’s more, turning state power on other religious minorities — I am truly at a loss for words to describe my reaction to seeing photos and video of arrests being carried out while Muslim students were praying maghrib. First and most importantly, it is simply wrong. And second, I am acutely aware that anything that the state can do to a Muslim minority it can ultimately do to a Jewish minority as well. The actions of the NYPD on campus this week sanctioned by your office have not made us safer and have instead enacted a permission structure for repressing not only political but religious speech.

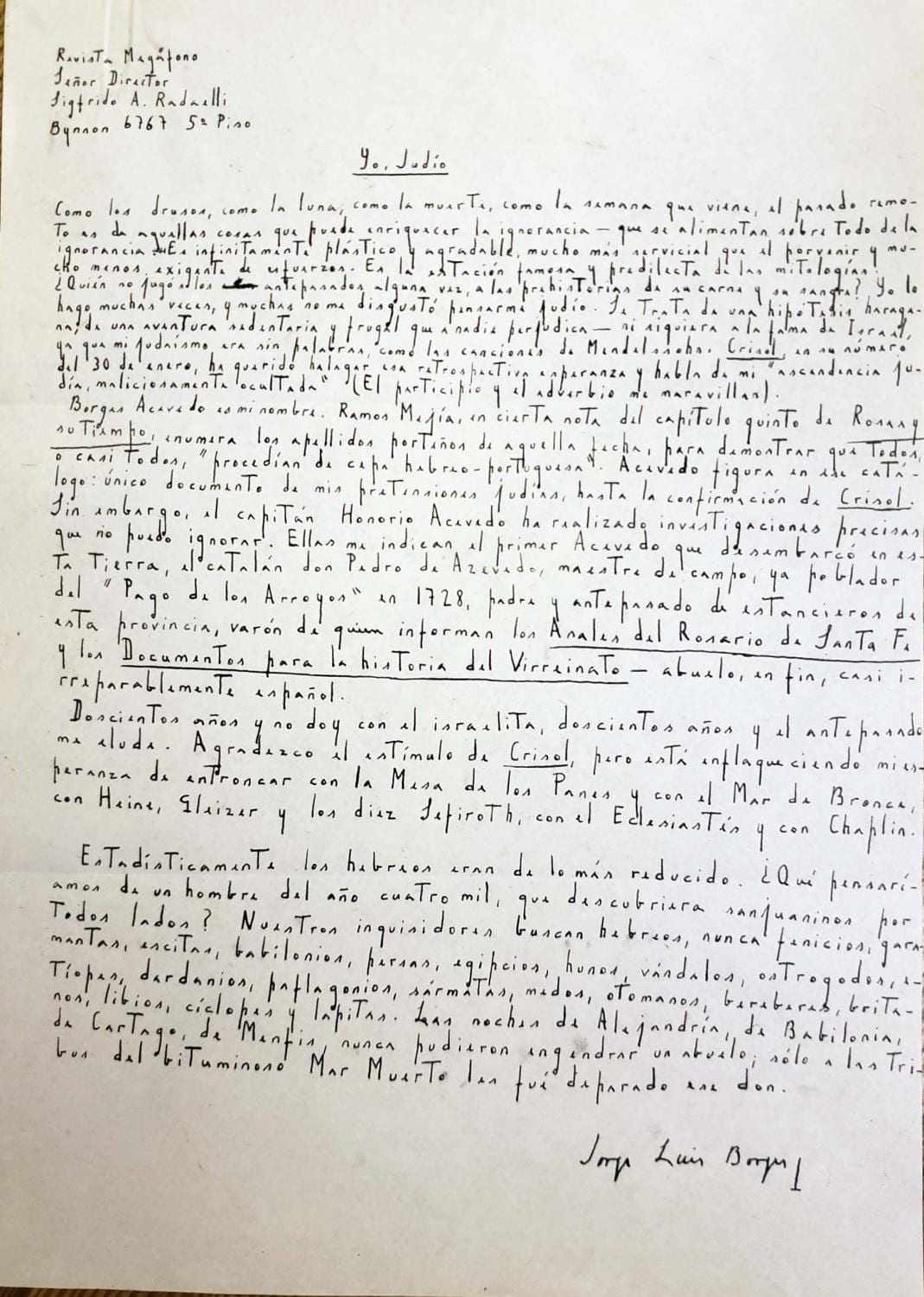

I know through my own area of academic expertise, namely the intertwined intellectual history of Jews, Christians, and Muslims in medieval Spain, that members of the same and different religions can disagree fiercely, pray differently, and sometimes even insult each other polemically while most of the time still managing to walk the fine line of coexistence, resolving tensions through thoughtful engagement and agreement to disagree; based on what I know of your work as a filmmaker, I suspect you know this, too.

I urge you in the strongest possible terms to reconsider your position. Please: do not impose punishments on the students who have exercised their freedom of expression this year and especially this week and do not sanction my colleagues who were arrested while trying to protect them. Treat their demands as demands to be addressed on their face and not as trespass against the university or any of its constituent communities. And barring real violence, please do not breach the trust of our university community by inviting the police to arrest students and faculty on campus. In short, please uphold the university’s own existing commitments to student and faculty freedom of expression and the right to protest.

I appreciate your consideration of my concerns.

Sarah Pearce

Associate Professor, Department of Spanish and Portuguese