I used to have this friend. For a lot of reasons we grew apart. Ultimately, it was one of those grad school friendships that didn’t survive one and then both of us no longer being in graduate school. I might have tried to hang on longer if I hadn’t felt like I had taken on the role of being the friendly local Jewess whose very being could debunk the kinds of myths believed by people who grow up in parts of the world and the country where they might not have ever met any Jews, and if I hadn’t felt like I was failing at it. She’s the sort of person who thinks she can identify Jews — strangers, classmates, faculty — by the size of our noses or who will start out an anecdote by mentioning that one of the people involved “is Jewish — no offense” as if it were an insult.

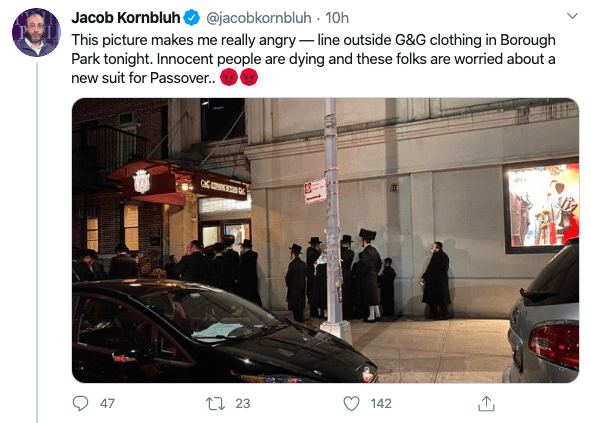

There are other reasons for it, too, but we’re not in touch anymore; and that’s entirely on me. I don’t wish her ill. I hope she’s doing well, whatever well means to her; and I do occasionally look at her social media to see if that’s the case. In the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, a Jewish journalist posting a photo of a line of men in coats and streimels and black hats waiting to buy suits for Passover; the journalist commented that he found this phenomenon infuriating.

My former friend replied to him:

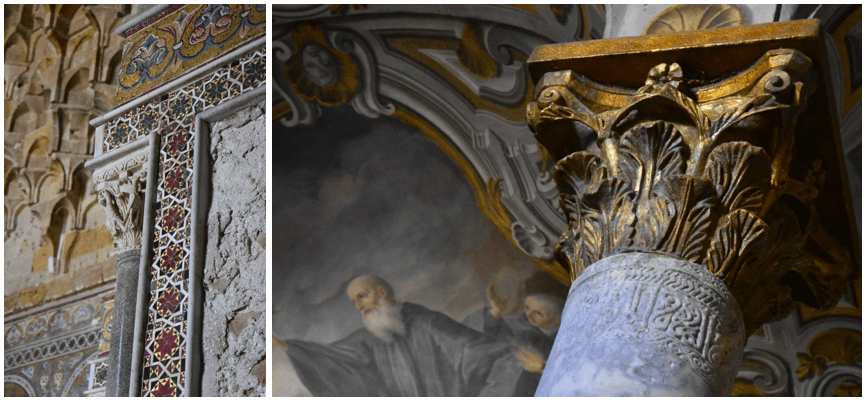

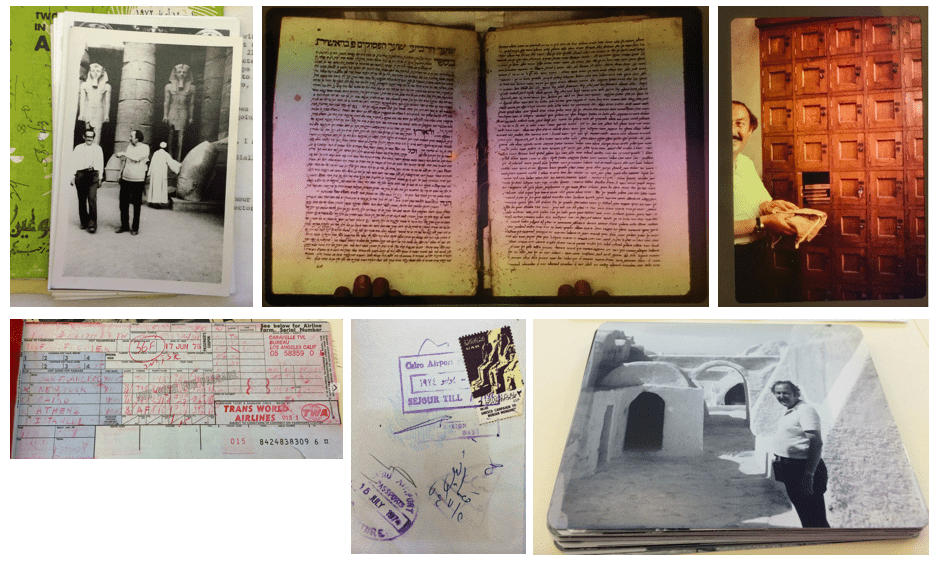

I’m teaching an introductory lecture course on medieval Spain this semester as part of NYU’s core curriculum, and we are nearing the lecture in which I will discuss the fourteenth-century legends and the rhetoric that grew up around Jews as unique and malicious vectors of the plague, legends and rhetoric that have persisted until today. It’s less flashy than the neo-Nazis who march with tiki torches, afraid that Jews will “replace” them, but it’s still an anti-Jewish myth that has persisted — in forms that change over time, of course — since the Middle Ages.

Let’s start with some statistics. The measles outbreak in Marin County, CA, was the result of a huge percentage of parents refusing to vaccinate their children for non-religious philosophical reasons. The United States was within days of no longer being considered a country where measles is eradicated; we’re not a big enough or spread out enough part of the population at large for that to have happened if measles were a Jewish problem. The bottom line is that yes, there are people in Jewish communities who are wrong on public health issues in ways that perpetuate harm. But there are also people in non-Jewish communities who are wrong on public health issues in ways that perpetuate harm. Thinking that you know better than physicians and epidemiologists or that you don’t have to pay attention to the wider world, whatever the foundation of those beliefs, is not an inherently Jewish trait. People are people in both the wonderful and the deeply stupid ways they engage with the world; but people tend to highlight it and act on it when it’s Jews in the wrong.

I’m planning to do my coronavirus semester posting here rather than on FB, even though the latter is the more usual space for academic discussion. (Although maybe there’s a chance that the current crisis will breathe some life back into the academic blogging community?) This feels like a singular moment, and so I don’t want my posts to disappear down into the bowels of the FB juggernaut once this is over. So:

I’m planning to do my coronavirus semester posting here rather than on FB, even though the latter is the more usual space for academic discussion. (Although maybe there’s a chance that the current crisis will breathe some life back into the academic blogging community?) This feels like a singular moment, and so I don’t want my posts to disappear down into the bowels of the FB juggernaut once this is over. So:

Was put on a special diet with only ten foods allowed. Amongst those were ham, eggs, and lavender tea. No vegetables anywhere on the list. I decided it was stupid and I was going to eat some romanesco.

Was put on a special diet with only ten foods allowed. Amongst those were ham, eggs, and lavender tea. No vegetables anywhere on the list. I decided it was stupid and I was going to eat some romanesco.