Best passing material-book/scribal culture remark: “‘I can read the first few lines and these in the middle of the second page, and one or two at the end. Those are as clear as print,’ said he, ‘but the writing in between is very bad, and there are three places where I cannot read it at all.'” — “The Adventure of the Norwood Builder,” Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, The Complete Sherlock Holmes

Fictional shacks that are larger than my bedroom: Black Peter’s cabin in “The Adventure of Black Peter,” Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, The Complete Sherlock Holmes

Something I’d like to go back and tally: The number of bicycles in the second half of The Complete Sherlock Holmes

Don’t ever tell me my line of work is too obscure if a prize-winning, best-selling novel can just casually quote the Mozarab jarchas: Señales de humo by Rafael Reig

Of course a literary manual for cannibals is going to be a two-parter: La cadena trófica also by Rafael Reig

Madrid books: See above — they’ve got a super sense of place.

Italy books: Venice: Pure City by Peter Ackroyd; Venice, an Interior by Javier Marías (which was originally a longish newspaper essay and was only ever published in chapbook form in English and Italian translations); Day after Day by Carlo Lucarelli, translated by Una Stransky, audiobook read by Daniel Philpott

Cambridge/Granchester book: Sidney Chambers and the Shadow of Death by James Runcie

Israel books: The Mandelbaum Gate by Muriel Sparks; Someone to Run With by David Grossman; Volverse Palestina by Lina Meruane

(Bonus shocker of the year: Nick Hornby was totally right about Muriel Sparks!)

More Cuba books, because I am still haunted: Caviar with Rum, eds. Jacqueline Loss and José Manuel Prieto; Cuba in the Special Period, ed. Ariana Hernández Reguant; Dreaming in Russian by Jacqueline Loss

Michigan books: All-American Yemeni Girls by Loukia Sarroub

Because moving to Ann Arbor marked the first time I had to wrangle my cat onto an airplane: Catwings by Ursula K. LeGuin

Thought I would be okay taking these books on a trip and leaving them behind but definitely wasn’t: The Cooking Gene by Michael Twitty; The Library Book by Susan Orlean

Thought I would be okay taking these books on a trip and leaving them behind but definitely wasn’t: The Cooking Gene by Michael Twitty; The Library Book by Susan Orlean

Was completely fine leaving this on the airplane when I finished it: Kitchens of the Great Midwest by J. Ryan Stradal

Have we met?: The Pedant in the Kitchen by Julian Barnes

Hit too close to home to finish: Iphigenia in Forest Hills by Janet Malcolm

Much too much to distill into one pithy comment: Barracoon by Zora Neale Hurston

Best babushka: Ali’s Russian mother in Ali and His Russian Mother by Alexandra Chetriteh, translated by Michelle Hartman

Ironically, didn’t tell me much I didn’t already know: The Death of Expertise by Tom Nichols

And perhaps less ironically, White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo, which seems to have been written for people who just haven’t been paying any attention at all

Ironically, written at a pace that made me more anxious: Notes on a Nervous Planet by Matt Haig

Because apparently being in a relationship means attempting to share in your partner’s interests, even when those interests are Melville: Billy Budd and Other Stories by Herman Melville

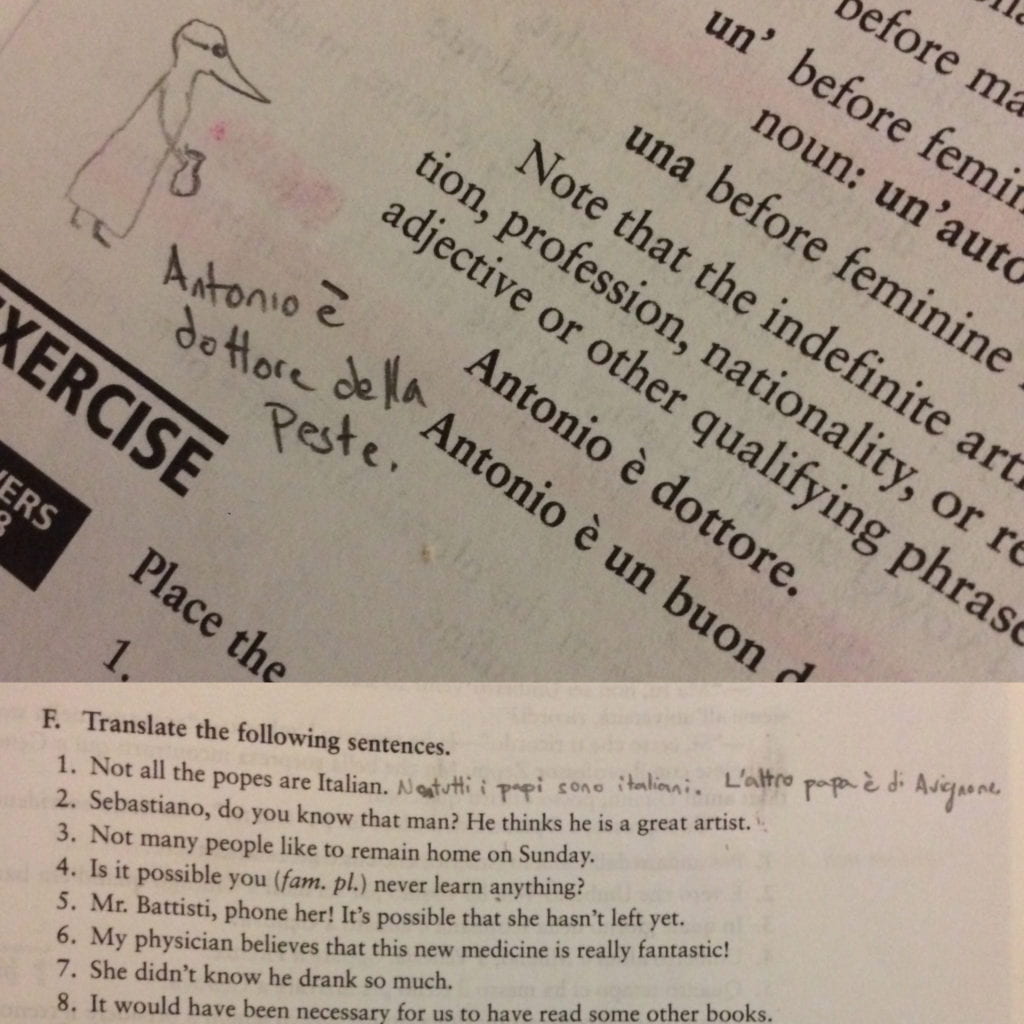

Because it’s hard to be patient when learning a language in which one has much better reading comprehension than ability to generate verbal forms: In Other Words by Jhumpa Lahiri

Because, 2018: Not All Dead White Men by Donna Zuckerberg; Infidel by Pornsak Pichenshote; Holocaust Tips for Kids by Shalom Auslander

***

2018 favorites: The Mandelbaum Gate, Billy Budd, Barracoon, The Library Book

***

I have a huge fantasy that I’ll read about six more books before the end of the year, but if it happens, those’ll have to go onto next year’s roundup because reading for pleasure shouldn’t have high-pressure deadlines. Happy reading, all!

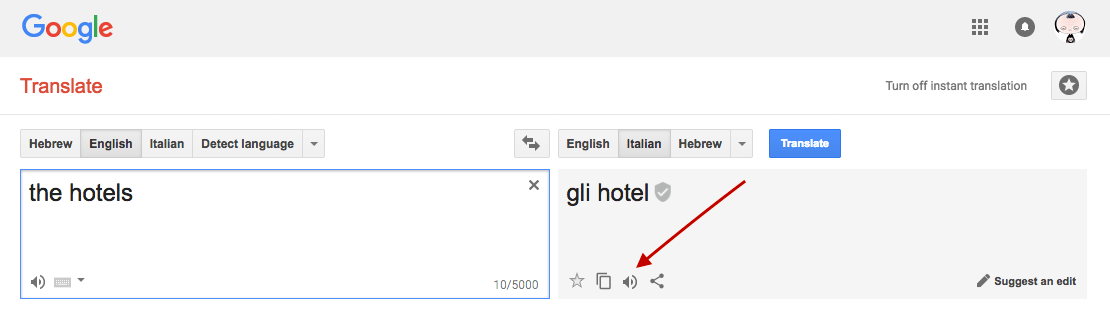

nd not a lot of context for place except in un ristorante del centro. I’m finding that my brain is filling in the gaps in Arabic: i peperoni sono fī l-jannah. On the one hand, it’s super unhelpful, but on the other hand it’s kind of an interesting insight into how the brain stores and processes foreign languages.

nd not a lot of context for place except in un ristorante del centro. I’m finding that my brain is filling in the gaps in Arabic: i peperoni sono fī l-jannah. On the one hand, it’s super unhelpful, but on the other hand it’s kind of an interesting insight into how the brain stores and processes foreign languages.

This is a lightly edited version of the comments that I made following Eric Calderwood’s talk at the Colubmia Workshop “Sites of Religious Memory in an Age of Exodus: The Western Mediterranean.” Part of the reason I’m posting my response is precisely because it is dependent upon reading his new book,

This is a lightly edited version of the comments that I made following Eric Calderwood’s talk at the Colubmia Workshop “Sites of Religious Memory in an Age of Exodus: The Western Mediterranean.” Part of the reason I’m posting my response is precisely because it is dependent upon reading his new book,