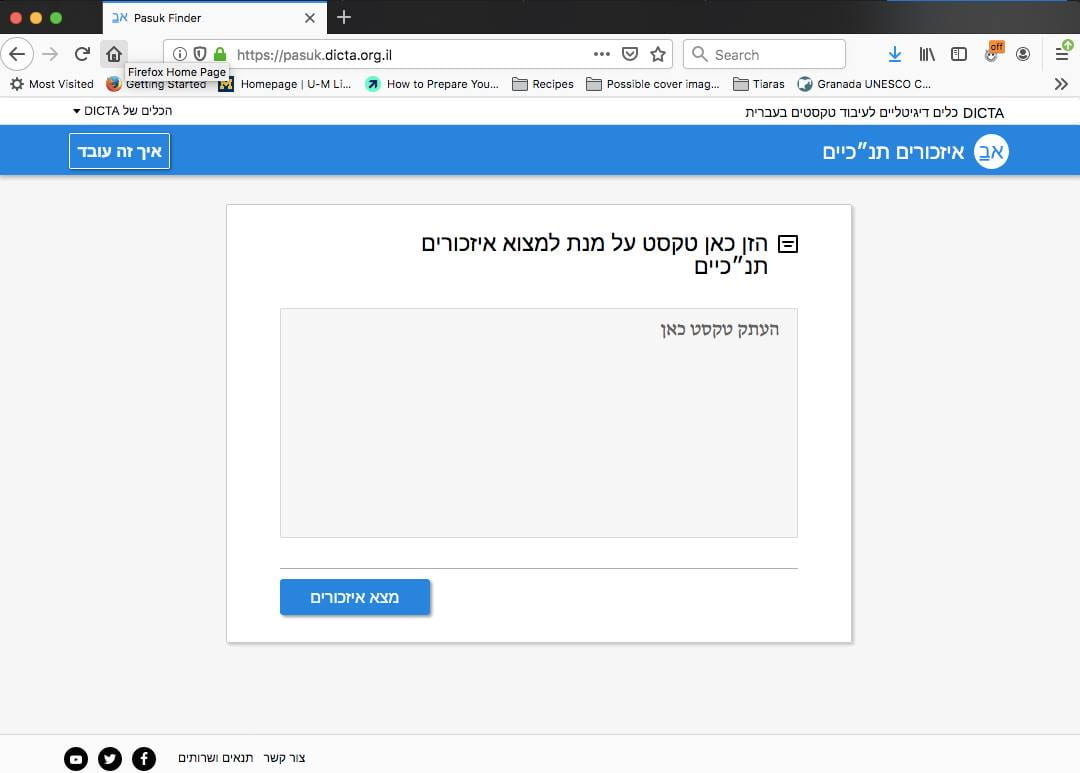

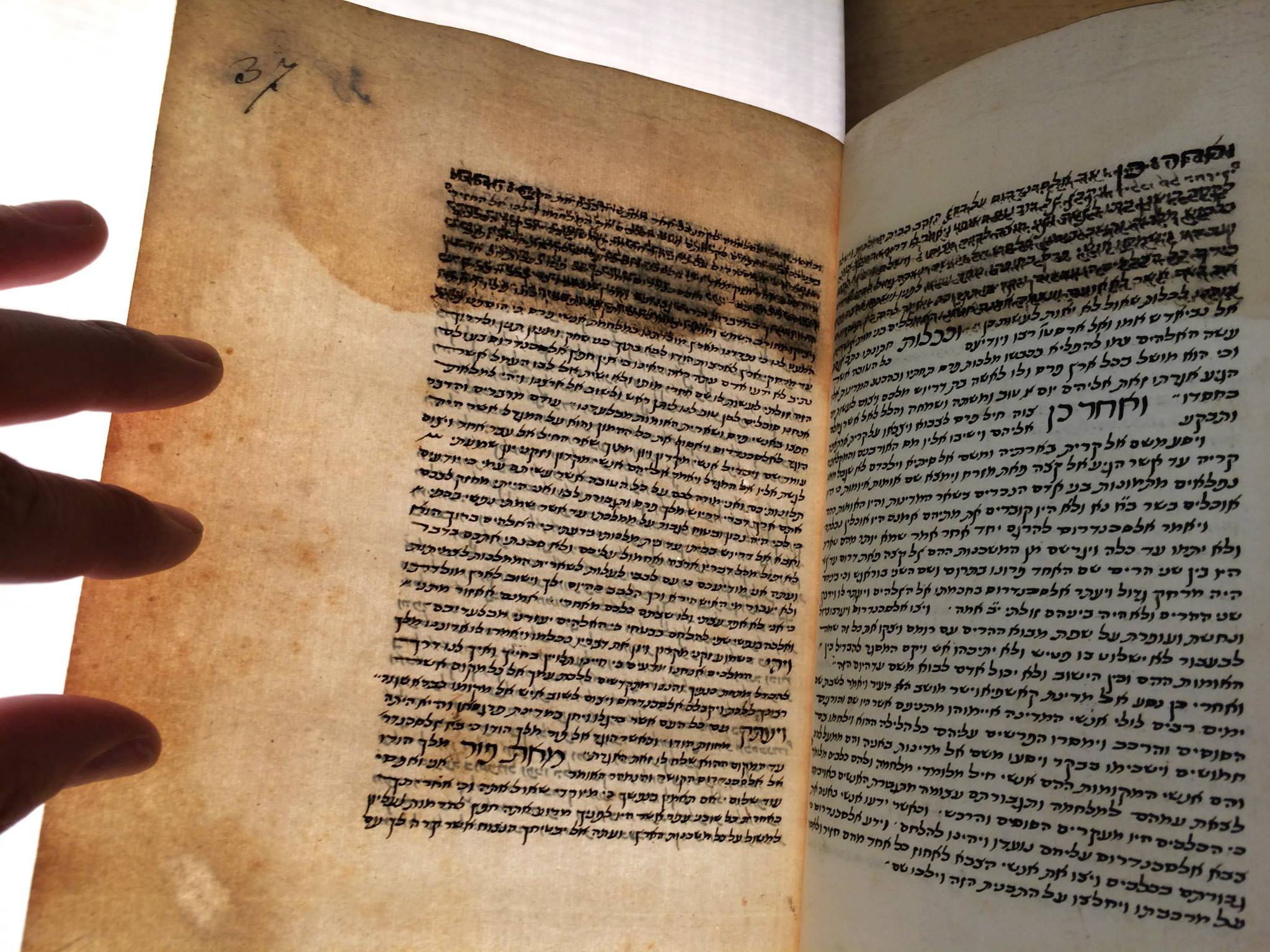

This is a screen-grab from a digital tool, PasukFinder, that I’m currently using to compare the biblical quotations in the original Spanish version of Don Quijote with the biblical quotations in four different Hebrew translations.

This is a screen-grab from a digital tool, PasukFinder, that I’m currently using to compare the biblical quotations in the original Spanish version of Don Quijote with the biblical quotations in four different Hebrew translations.

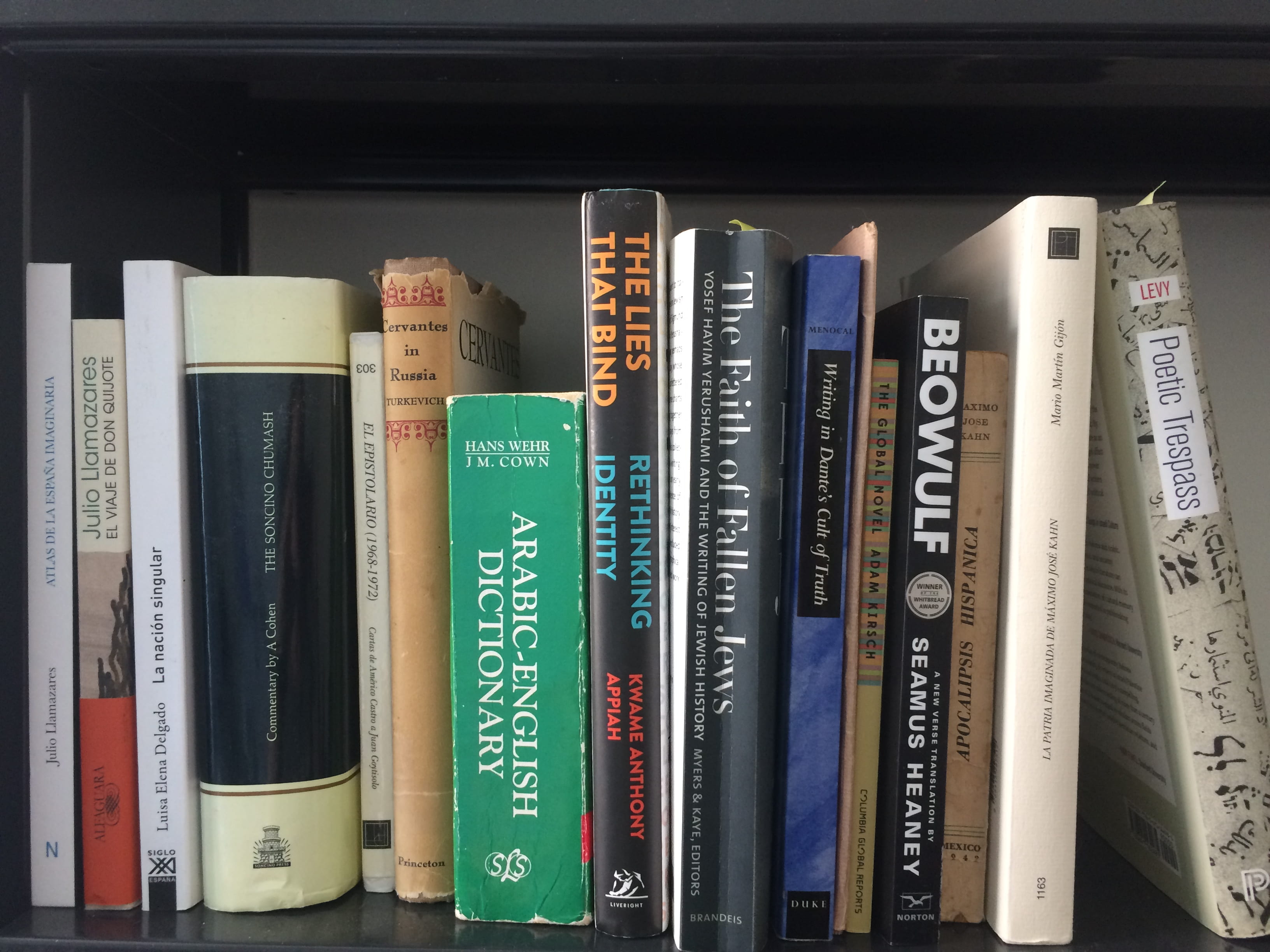

I was really lucky to have come. up in the profession and in life surrounded and preceded by a cadre of amazing women scholars at Yale. These are books by a selection of them.

This is an opening of Beinecke Hebrew MS Add. 103, formerly of Jews’ College London. It is a Hebrew-language life of Alexander the Great translated from a now-lost Arabic version. The colophon of the manuscript falsely attributes the Hebrew translation to Samuel ibn Tibbon, the Hebrew translator of many important works of Arabic philosophy, most notably Moses Maimonides Guide of the Perplexed. The translation was probably composed in the middle of the 12th century, a period when the roles of author and translator are becoming more well defined. And although (at least in broad strokes) the role of the translator was much more circumscribed and limited than that of the author, prestige would still accrete to a text by virtue of claiming for itself a famous translator.

(This is a text and a set of ideas that came out of my first book and that I’m just about ready to go back to in the interest of pursuing a line of inquiry — a comparative study of changes in attitudes toward the role of the author versus the translator — in both Semitic and Romance texts in this period. I’m hoping to start tackling it toward the end of this year. Suffice it to say, I’ve lots more to say about this topic, so maybe it’s just as well that I’m limited to a short post by virtue of being on my iPhone and mid-moving…)

I’m moving this week, so I can best show my current interest with the few books that I left unpacked to work on the introduction to my current book project and the chapter that I’m currently writing. The book is a reception history, examining the ways in which medieval poetry and poets from al-Andalus are implicated in various nationalist discourses of the 20th century. I’m reading and writing about different modes of constructing national identity and how different facets of it (language, religion, race, geography, etc.) function for the various nationalist writers whose work I am analyzing.

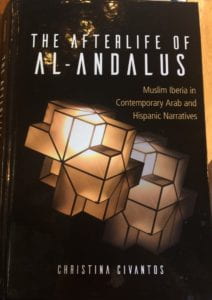

The book that I’m actively reading is Christina Civantos’ The Afterlife of al-Andalus (SUNY Press, 2017), which looks at traces of Andalusi literature in Argentine and Palestinian writing. I’m finding it to be an engaging book because I don’t understand the medieval history in the same way that Civantos does in order to set up the foundations from which she can carry out a postcolonial analysis of post-Andalusi literary works. And so it’s challenging me to more carefully articulate how I’m thinking about empire and governance in medieval Spain and its consequences in the modern world for the introduction to my own book.

And for non-academic (but not totally unrelated) purposes, I’m reading The Making Of, which is a series of interviews with the key players who were involved in the renovation of the Royal Museum for Central Africa, just outside of Brussels, which I visited last month. It’s funny how reading sometimes, completely coincidentally, groups thematically: I’m doing a lot of reading in postcolonial theory at the moment, both in and out of my academic life.

The Lone Medievalist group is hosting a photo sharing challenge for the month of August. I’ll be posting on Twitter and here in order to give myself some extra space for captions. Some of the categories are easy to tackle in 280 characters, but others will require more explanation and categorization; plus, it seems like a good a good excuse to get myself back into my daily morning-writing habit. I may not post every day for every category — some of them just don’t speak to me and I’m moving back to New York the first week of the month, so my internet connectivity will be a little dicey — but in the spirit of the thought exercise, I’ll try:

As a result of this brief review of The Myth of the Andalusian Paradise, I was invited to submit a chapter to an awesome forthcoming Routledge volume entitled The Extreme Right and the End of Historiography, in which I was able to return to the chapter that I walked through very quickly in the blog post review and give historical and historiographic context in greater depth and go into more detail about the problems in the book with more examples and specifics. After the pushback I got from right-wing commentators both on the blog and on Goodreads complaining that I was talking about historiography and interpretation rather than facts as such, I had a space to lay out a really detailed, textually grounded case against the book. And in fact, my first draft ran to sixty pages and still didn’t address all of the mistakes and misrepresentations in a single chapter and the historiographic context in which they were committed. One of the sections that I’ve cut is only tangentially related because it concerns the epigrams within the chapter rather than the body of the text itself; however, I wanted to post it here because it is also one of the clearest-cut cases of the ways in which Fernández-Morera distorts material and draws upon the work of hate groups; and it raises the question: If he can’t even represent short quotations in a few epigrams honestly and correctly, why should his readers trust the rest of his readings and analysis?

***

Epigrams as a Test Case for Textual Fidelity

The structure of each chapter of The Myth alternates between a series of epigrams that represent Fernández Morera’s antagonists and his argument against them. Our present case study, chapter six, opens with the following observation by the author:

“As the epigraphs in this chapter indicate, it is widely believed that Islam granted to Spain’s Jewish community, composed largely of Sephardic Jews [sic, see above], a substantial degree of liberty and tolerance. According to this view, the idyllic life for Spain’s Jews was interrupted by the invasion of the ‘fanatical’ Almoravids and Almohads, and later by the ‘intolerant’ Christian kingdoms during the Spanish Reconquista. However, the fact of the matter is that the life enjoyed by the Sephardim, within and without their communities, was full of limitations long before the invasion of the Almoravids and Almohads, and that the Catholic kingdoms eventually became a place of refuge for Jewish families.”[1]

This opening sentence sets up the epigrams as representative of key positions that the author plans to refute. Yet by bowdlerizing even these citations, he calls into question his treatment not only of the scholarship in the field but even of the primary sources themselves.

The first epigram is drawn from the article “Sephardim” on the web site Jewish Virtual Library.[2] It contains a brief overview of the history of Jews in Spain before moving on to its main topic, the Sephardi diaspora; it ostensibly illustrates the attitudes of the mainstream, liberal scholars against whose work Fernández-Morera sets his own. The quoted passage reads: “The era of Muslim rule in Spain (8th-11th century) was considered the ‘Golden Age’ for Spanish Jewry. Jewish intellectuals and spiritual life flourished and many Jews served in Spanish courts. Jewish economic expansion was unparalleled.”[3] An examination of the article in its entirety reveals it to be compromised by erroneous information on both the small-detail and big-picture scales. Some of the errors are relatively minor (although not insignificant), such as giving the date of the conquest of Toledo by Alfonso VI as 1089 instead of 1085 and implying that Muslim rule ended in the Iberian Peninsula in the 11th century. But other errors reveal a broader misunderstanding of the religious history of al-Andalus, misunderstandings upon which Fernández-Morera is willing to hang his own argument. Again, by way of example, the article writes that Jews treated Arabic as a replacement for Hebrew; in fact, though, rabbinic authorities were clear that when Arabic was used in a Jewish liturgical context (and not all such authorities permitted it), it was to be used to supplement, rather than replace, the Jewish sacred languages of Hebrew and Arabic. Of greatest consequence for the political and religious stakes of Fernández Morera’s book is an erroneous description in the article of the evolution of Christian belief in Visigothic Spain: Following an explanation of Visigoths’ religious beliefs, namely that they adhered to the apostolic Arian Christian faith before converting en masse to Catholicism in the year 587, the article’s section on Visigothic rule concludes with the assertion that “in 638 C.E., the Arian Visigoths declared that ‘only Catholics could live in Spain,’”[4] thereby demonstrating a fundamental misunderstanding of the religious sea-change that took place by virtue of that conversion of and the incompatibility of Arian and Catholic belief. By selecting this article as the source for his epigram Fernández-Morera can seemingly support his contention that writing on medieval Spain ignores or misrepresents Christian history when this is in fact a broader pattern of errors in the article “Sephardim” and not exclusive to the history and theology of Christianity. Some bad work will always be published regardless of its politics; that does not make it representative of the state of the field or the quality of its scholarship as a whole. And as a popularizing encyclopedia article, it is also not representative of the kinds of academic studies with which Fernández-Morera claims to be taking issue.

In addition to choosing a weak, straw-man adversary in the form of this epigram, Fernández-Morera has chosen one from a site that makes its political leanings clear; and they are not ones that support his overall argument about the liberal biases of the academic study of medieval Spain. The Jewish Virtual Library is digital encyclopedia project of the non-profit organization American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise; its web site fawningly sports quotations from right-of-center politicians Benjamin Netanyahu[5] and Donald Trump speaking in their capacities as the heads of their respective governments.[6] Rather than illustrating that liberal professors are the sole source of his pernicious imagined myth of al-Andalus as a paradise he instead shows that positive portrayals of Islamic Spain can also be promoted in popular sources supported by right-wing political and religious organizations and that those portrayals can be made to serve right-wing agendas. He has taken an example of sloppy writing about the topic from a right-wing web site and implicitly passed it off as an example of what is wrong with left-wing popular writing on the topic.

As another example of supposed visions of al-Andalus that incorrectly promote a picture of tolerance occurs in the second epigram in the chapter:

“The years between 900 and 1200 in Spain and North Africa are known as the Hebrew ‘golden age,’ a sort of Jewish Renaissance that arose from the fusion of the Arab and Jewish intellectual worlds. Jews watched their Arab counterparts closely and learned to be astronomers, philosophers, scientists, and poets. At its peak about one thousand years ago, the Muslim world made a remarkable contribution to science, notably mathematics and medicine. Baghdad in its heyday and southern Spain built universities to which thousands flocked. Rulers surrounded themselves with scientists and artists. A sprit of freedom allowed Jews, Christians, and Muslims to work side by side.”[7]

Fernández Morera attributes this quotation to an article by Francis Ghiles in a 1983 article in the journal Nature entitled “What is Wrong With Muslim Science?”[8]; however, his citation is only partially accurate. Ghiles’ article is in fact a review of a book review of Ziauddin Sardar’s 1982 monograph Science and Technology in the Middle East,[9] a volume that is in fact critical of overly-rosy presentations of science in the Islamic Middle East. The Nature review of that book actually opens with the portion of the text cited by Fernández-Morera beginning with “at its peak” and continuing through the end of the citation. The first two sentences appear nowhere in Ghiles’ review; instead they come from the FAQ section of a web site called Jews for Allah, which appears to be aimed primarily at encouraging Jews to convert to Islam.[10] In response to a query about the role of minorities in Islamicate civilizations, the FAQ section introduces Ghiles’ review with those two sentences as an editorial response to the question and then quotes the opening sentences of Ghiles’ review to support that response.[11] In other words, the text as cited in Fernández-Morera’s epigram are cited from Jews for Allah rather than directly from the review; the author erroneously combines the web introduction with the citation from the book review. In doing so, he demonstrates that instead of referring to the texts he claims to have cited he instead uses a web site representative of a strain of modern Islamic antisemitism[12] in order to backform his own fantasy about medieval Islamic antisemitism (which will be discussed in greater detail in the following section). This particular epigram, then, demonstrates flaws in handling sources, recourse to teleological analysis, as well as a reliance upon information gleaned from hate groups.

In addition to misrepresenting its original source and incorporating ideas from a hate group’s web site, this epigram manifests other problems as well. Even as it is presented, erroneously, this epigram does not further an ideology of Andalusi exceptionalism, or the idea that al-Andalus was the uniquely tolerant haven for religious minorities in the Middle Ages. The first source of this combined quotation treats Spain and North Africa correctly as a single geographic and cultural unit,[13] and the second source in the quotation talks about the intellectual innovations both in al-Andalus and in the Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad. In other words, the epigram shows that the idea of tolerance and intellectual flourishing in the Islamic world are not limited to discussions of Islamic Spain, which is itself not treated as an exceptional entity unto itself but rather as a part of Islamicate world systems; the epigram does not, then, serve as evidence for his argument but rather demonstrates its exact opposite.

One of the ways in which this book operates is to interpret selectively and without direct recourse to the primary sources; this is clear simply from a review of the epigrams, and will be demonstrated in greater detail with respect to the body of the work itself in the following section. Fernández-Morera protests much in his introduction that his work’s strength is based on his direct consultation with sources, yet even the epigrams with which he illustrates the problem his book is meant to counter are transcribed incorrectly and indirectly. He asks the reader to trust his analysis of complex medieval sources written in many languages and mediated through the judgment of editors and translators[14] while proving that he does not even go directly to easily accessible[15], contemporary, English-language sources.

Footnotes below the jump.

Continue reading “Paradise Still Lost: Epigrams as a Test Case for Textual Fidelity”

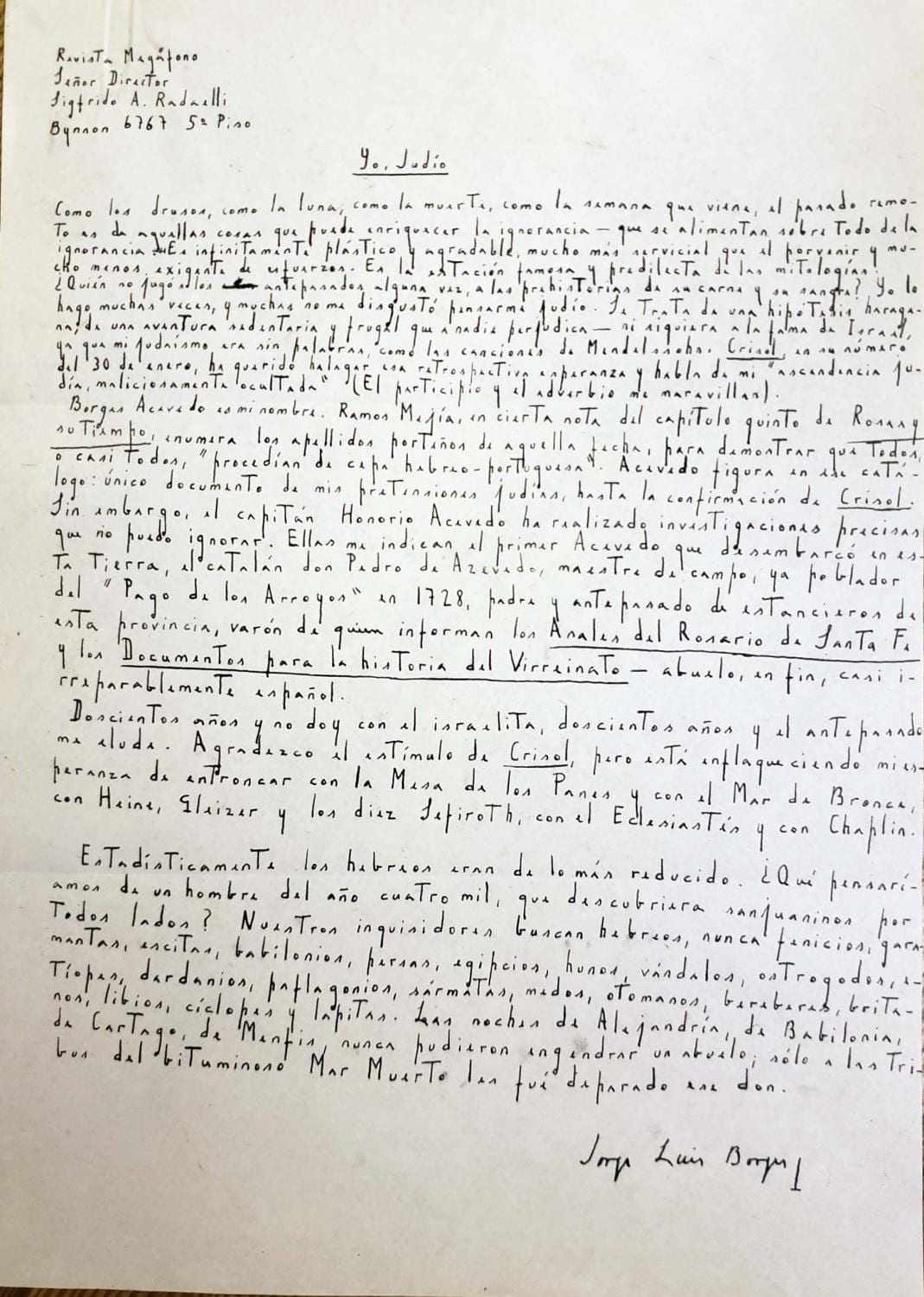

Eventually, I would like to write something about this very short essay by Jorge Luis Borges. I had tried to work an excursus on it into a review essay I’m writing, but it just wasn’t working and read very forced. It’s now sitting in a file called “cut bits from review essay.docx.” (I will just note that with Borges being the writer he is, I did actually track down his reference to Ramos Mejía, and it exists as it is reflected in this essay.) So for now, I’m just sharing the text, because it’s one of those things I think everyone should read. This is allegedly an image of the original manuscript copy, currently for sale in a Buenos Aires bookshop (anyone have a spare $24k they don’t know what to do with?); I’m not enough of a Borgista to know if this is really his hand or not. In any case, it’s very clear. Read on.

I edit my CV down. Nothing I did in grad school is there anymore. The undergraduate senior essay prize I was so proud of came off when I got my first job. Talks I’ve given in more minor circumstances or that I’ve given more than once aren’t all there anymore. I keep a running complete list in my own files, but nobody looking at my vita needs to be bored with every last conference presentation I’ve ever made, and now that I’m (shudder) a mid-career academic, the things I did very early on just don’t matter that much anymore.

I’m editing my CV now for the end of the academic year and in anticipation of being able to share a new accomplishment when it’s announced publicly in the coming days. It’s a good stock-taking exercise, too. I realized that this year is the year that my book reviews all spiraled out of control into full-length essays, which has occasioned a chance to think about the kind of work I want to do and how I might situate myself as a historiographer as well as a cultural historian.

Soul-searching vis-a-vis the field of Medieval Studies and its history and implication in the current edition of the culture wars has returned to the fore in the wake of a NYTimes article published over the weekend that presented issues of race and white supremacy in and around the field as a series of social media spats as much as anything.

In the wake of this, I’m in New York to see the first half of Wagner’s Ring Cycle at the Met Opera. (The logistics are complicated; I had initially planned to be back to New York from Michigan by now and bought my tickets based on that assumption. I’m not, but I was able to schedule some meetings on campus in conjunction with a workshop I co-led at Cornell over the weekend, such that the timing worked out for me to be able to at least see the first half. Be that as it may.) Wagner is, of course, all kinds of implicated in genocidal white supremacy. But I love the music and, as Ernst Bloch (whose Avodat Kodesh I also love), I’m not prepared to cede it to the Nazis. The Ring is not particularly subtle, which is part of why I like it. It’s big and bombastic. It’s also very obvious the ways in which it originated in German nationalist folklore and how and why it appealed to Hitler. I can appreciate the music while utterly renouncing the convictions of the composer and the ways in which his work was put to political use. That’s what I meant when I wrote this tweet:

I was almost immediately questioned aggressively by the two directors of an open-access academic press who tweet in the voice of a corporate “we” that I find oddly disquieting. My interactions with them in the past have begun with equal measures of bombast, self-righteousness, and aggression. It, as the kids these days say, escalated quickly.

I’m not sure why this press feels that it is the position to paternalistically “offer” me the “opportunity” to explain myself or is entitled to an answer, what one of its editorial directors hating Wagner has to do with it, or why my disinterest in talking to a hostile, disembodied, corporate “we” in 280-character bursts means that I’m a white supremacist, but here we are.

As much as white, Christian progressives in my field are signing onto a kind of “cancel culture” that demands renunciation of works of art created by despicable people who hold views inimical to their individual lives, I don’t have that luxury. If I were to give up every work of literature written by an anti-Semite, the horizons of my written world would become small and impoverished. (Don’t tell, but I love T.S. Eliot, too.) I’ve written, too, about how as an Arabist I don’t have the luxury of not using a dictionary that that was written for the express purpose of translating Mein Kampf into Arabic. As a Hispanist, I don’t have the luxury of not dealing with archivists and librarians who held positions, and gladly, in Franco’s government. It’s easy and satisfying, I’m sure, to renounce all of these things and be done with them. It’s harder but more necessary to live in the world as it is, working to mitigate the harms of reality.

I was really proud to have been awarded the Michael Camille Memorial Essay Prize in 2014 for work I did on the only surviving manuscript of Judah ibn Tibbon’s ethical will. To me, receiving an award named after an art historian affirmed the interdisciplinary nature of my work and my ability to speak to scholars trained in many fields of study, which, as the odd-duck Arabist in the back corner of a Spanish department, I have always seen as an important part of my academic portfolio. It was rewarding to have that work and those skills validated publicly. But the award is made by the journal Postmedieval and the Babel Working group, both of which are adjacent to Punctum Books and have heavy involvement from one of its editorial directors. As proud as I am of that award, I don’t really want a prize awarded by a body headed by someone who will so quickly and inaccurately fling about accusations of white supremacy, and fling them at me. So at least for the time being, in this round of editing down my CV, I’m going to remove that award. I already have tenure. I don’t need to prove myself through my CV in the way that I used to. In this instance I do have the luxury to be able to stand on principle now.

Lucky her she’s not a medievalist, but Roxanne Gay posted this recently:

If I could find a way to write this all up without making it sound simultaneously bonkers and like nothing more than Twitter-gone-wrong (as if a Twitter spat were the telos) I’d write to the editorial board and, five years on, decline the prize and return the money that came with the award. I’m still thinking it through, and I don’t know that I have the rhetorical skill to pull it off; Twitter truly warps a person’s thinking and writing when it all comes to this. The state of play right now is crazy-making. Instead, as it stands, I think I will handle this by making a contribution in the amount of the Camille prize, in Michael Camille’s memory, to an organization that I have worked for and support regularly that fights discrimination from within my own broader religious community directed at non-Orthodox Jews and, especially, Jews of Color.

I try to take seriously the responsibility of honoring the memory of the scholars who shaped my thinking and my work. (And in fact, another piece of my complicated appreciation of Wagner is due to the fact that he was the favored composer of one of my teachers, who not only taught me how to be a cultural historian, but also a human being. And so I listen to Wagner for myself, but also in honor of her memory.) Part of the reason I was so proud to have received an award in his memory is because it was his book on the 19th-century renovations of Notre Dame (it’s really all coming crashing, coincidentally, down in the last few weeks, no?) that introduced me to the ideas of medievalism and reception history as fields of inquiry. But for right now, I think that the best choice I can make is to take the award, and his name as it is associated with bad actors in the field who seem invested in maligning me, off my CV for a while and hope that better days will come when I can return it to its place.

If you’re a philologist or a nerd, it’s not the language of love. It’s the language of an unreasonable variety of articles and prepositions that you know you’ll never get quite right all of the time. It’s the language in which you hear the phrase “I’m going to visit my friend” reverberating from your mouth and only then remember that the verb visitare is used exclusively for going to the doctor’s office and what you are going to do is andare a trovare your friend. It’s the language whose numbers are just enough different from Spanish to give you trouble and you only remember cinquecento because Jeremy Clarkson makes fun of Fiat all the time on old Top Gear reruns on TV. It is the language that you insist, indignantly, to its native speakers that no, of course it’s not a difficult language — you speak Spanish anyway and have put in the time on Latin and Arabic — but silently admit to yourself that it’s not easy, either, and what did you need to go learn another diglossic language for, anyway? Dio là, as they say in Venetian, and definitely not in Standard Italian.

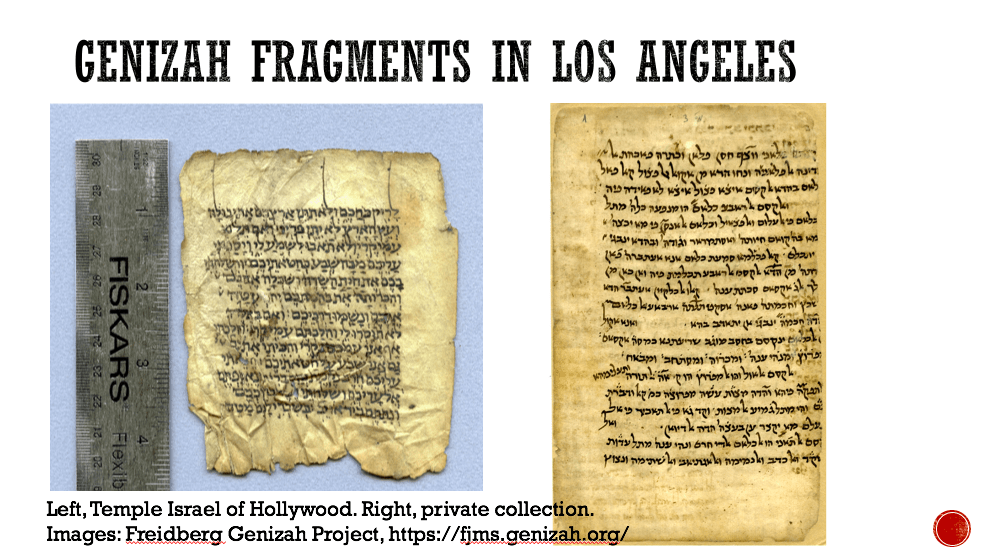

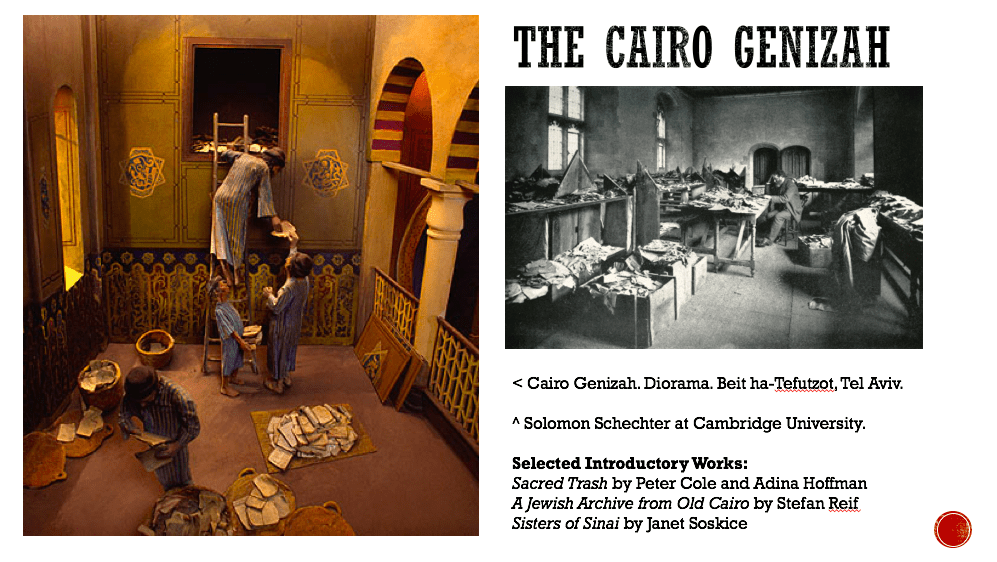

I was sort of rolling my eyes in boredom as I write, for the zillionth time, the “this is what the Cairo Genizah is and why it is both relevant and important for the literature of Spain” paragraph for a lecture I am giving at UCLA next week. And then I was reminded of a talk I gave a few years ago at a conference at Notre Dame, after which a Regius Professor of English approached me and thanked me for taking the time to explain what the genizah was. She had been, prior to her appointment at one of the other universities with Regius chairs, appointed at Cambridge, whose university library houses the vast majority of the Cairene disjecta membra. She told me that she had been to all kinds of medieval talks in which people threw around the word “genizah” but never explained it; the best conclusion she could draw was that “genizah” was some kind of booksellers’ district in Cairo that had been well preserved since the Middle Ages. I was tickled that someone so senior was so gracious and intellectually humble. And ultimately, the memory was maybe not a bad reminder of our responsibilities, especially as we move toward a field of Medieval Studies that is increasingly globalized, of the twin responsibilities to explain our own field knowledge and to really listen, with humility and an openness to learning, as others do the same.