It may be the easy way out, but I’m resorting to a screen grab of text in a word file as today’s photo…

It may be the easy way out, but I’m resorting to a screen grab of text in a word file as today’s photo…

One of the notable outbreaks of violence in medieval Spain came as the part of an incident known as the Córdoba martyrs’ crisis, in which a group of young Christians, unhappy about the acculturation of their peers and egged on by a powerful older cleric, sought martyrdom by repeatedly engaging in public blasphemy and refusing to backtrack when given the opportunity to do so. The martyrs’ lives are recorded in a hagiography by the cleric, Eulogius, who was himself ultimately martyred, too. There’s a new edition of Eulogius’ writings about to be published, edited by Kenneth Baxter Wolf, who also wrote a short account of the episode.

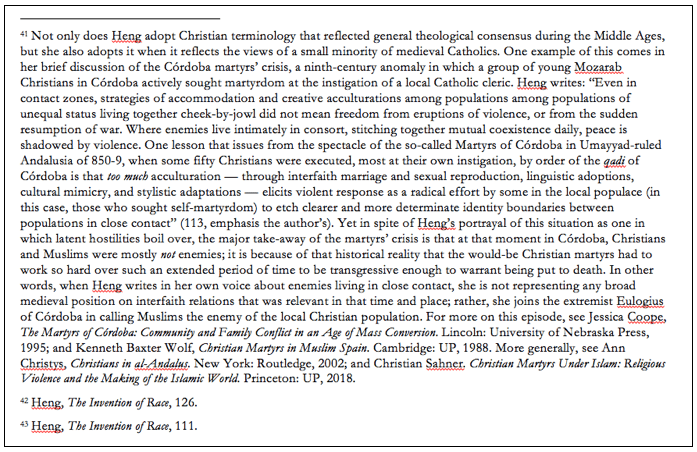

The screengrab that is my main picture for today is from a footnote in a forthcoming review essay I wrote about Geraldine Heng’s The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages, a book which has been received hagiographically, in the colloquial sense of the word, by my colleagues in medieval English literature. From my academic perspective it has a lot of problems; embodied in her treatment of the Córdoba martyrs’ crisis are her tendency to impose modern, popular views of Islam back onto the medieval period and her treatment of non-English materials without the appropriate context in terms of how non-English communities understood and talked about creating and managing racial difference.

The screengrab that is my main picture for today is from a footnote in a forthcoming review essay I wrote about Geraldine Heng’s The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages, a book which has been received hagiographically, in the colloquial sense of the word, by my colleagues in medieval English literature. From my academic perspective it has a lot of problems; embodied in her treatment of the Córdoba martyrs’ crisis are her tendency to impose modern, popular views of Islam back onto the medieval period and her treatment of non-English materials without the appropriate context in terms of how non-English communities understood and talked about creating and managing racial difference.

This year, I’m going to set aside a day for students in my history of Spanish class to play

This year, I’m going to set aside a day for students in my history of Spanish class to play