My intellectual lineage is such that it is perhaps inevitable that I will always think about poetry and music together. Once you accept that Bob Dylan has more in common with the Provençal troubadours than not, something breaks open in the theories of literature that govern your reading. I will always be a Clapton girl at heart, but the more medieval poetry that I have read, the more I have come to appreciate rap, hip-hop and R&B music. I know, I know — what a bougie, white-girl, academic way to come to those genres, but all the same, maybe that’s the point: Maybe medieval poetry maybe shouldn’t be quite so rarefied and reified in the canon.

For Black History Month, the Black Jewish writer MaNishtana shared music videos on Facebook featuring Black Jewish artists; that’s where I first came across this song, which draws heavily on the words of Psalm 23. I found it compelling on its own: I think that rhyming “so the world should know” with “le-ma’an shemo” (1:15) is pretty close to poetic genius — although I’ll admit I’ve always been a sucker for a solid bilingual rhyme.

I don’t think I’m really saying anything earth-shattering by pointing out the cultural-contextual similarities between rap music and medieval poetry; it’s certainly one that I’ve found useful in the past in teaching and in presenting medieval poetry to a lay audience. I’m writing this now more because I was just really grabbed by a new-to-me example of the phenomenon of sampling which is a striking demonstration of the ways in which Jewish poets draw not only from the Bible but from the literary, poetic, and musical traditions around them in their broader local communities.

This song plays with several modes of traditional Jewish writing, but also draws in its rootedness in hip-hop in a way that very much reflects the practices of the medieval Hebrew poets from Spain. The song uses medieval modes of commentary on a biblical text; it recourses to tropes about God and writing that we find all over medieval Jewish models; and it is bilingual and bicultural in ways that reflect the medieval Spanish Hebrew poets’ borrowings from other languages and the dominant cultural and literary contexts they inhabited.

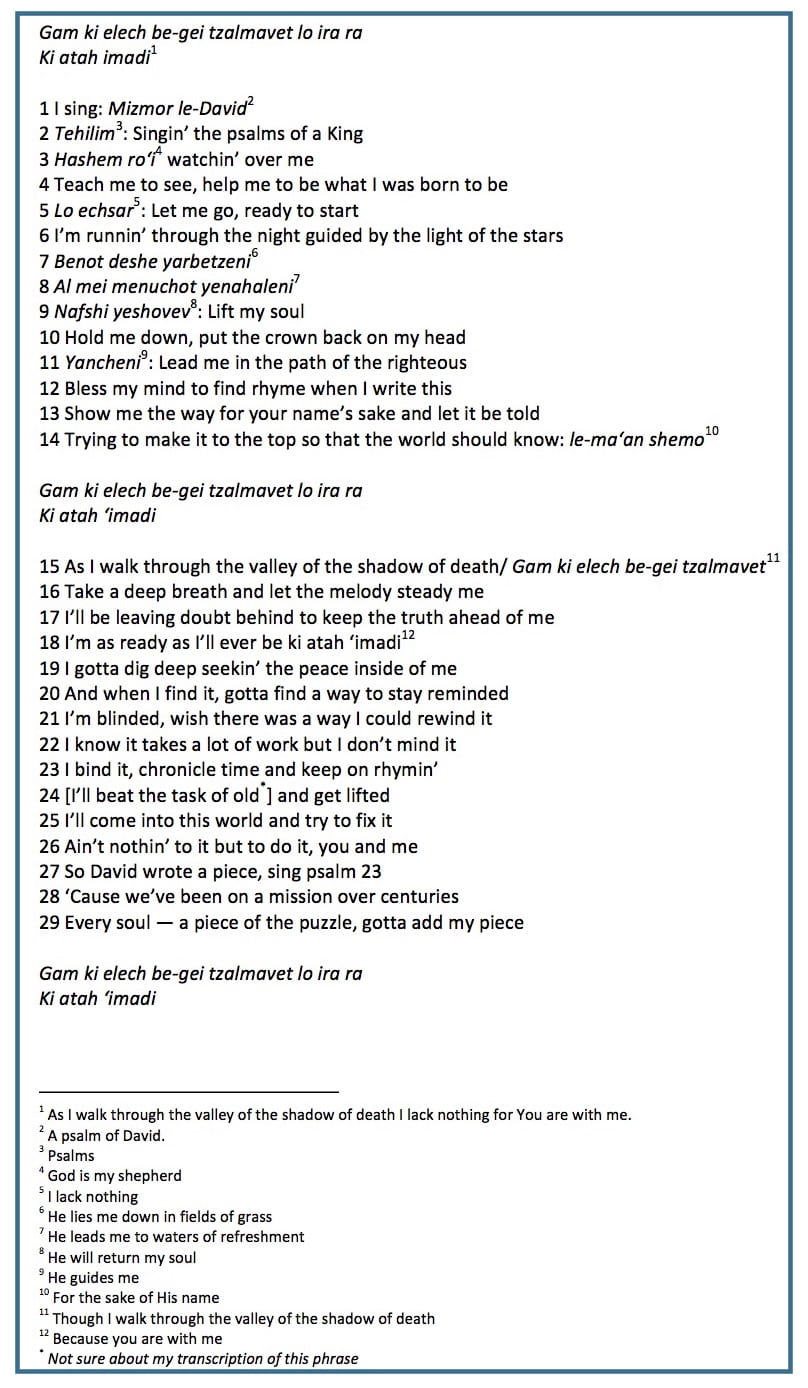

The song (especially the first stanza) works very much in the mode of medieval commentary on the text of the Hebrew Bible. I’ve transcribed the text out just to make it easier (inshallah!) to follow my argument.

In that first stanza, the English text works to define and to interpret the Hebrew text of the psalm. This happens in simple ways, such as in the first three lines, where the English is a fairly straightforward adaptation of the Hebrew. In line 3, for example, he interprets “Hashem ro’i” (God is my shepherd) with the phrase “watching over me,” which both explains the text and elaborates upon it within the limits of the ways in which the medieval commentators would define words and phrases. For example, when Abraham ibn Ezra comments upon that phrase when it appears in the first verse of the psalm, he writes: “When it refers to the shepherd, God is the shepherd who shepherds me and because of that I lack nothing.” In both cases, the interpreters of the text offer a fairly straightforward definition of what a shepherd does.

This kind of interpretation also happens in more complex ways, such as when Hebro interprets “lo echsar” (I lack nothing) in lines 5-6 with the phrase “Let me go, ready to start/ Runnin’ through the night guided by the light of the stars.” These two lines give a more complex understanding of how Hebro as a commentator understands what it means not to be lacking and what it allows the believer to accomplish. In lines 11 and 12 he interprets the Hebrew “yancheni” (guide me) by finishing the phrase from the psalm in English and then further explain the type of guidance he seeks or expects from God.

Sticking for a moment with those same two lines, 11 and 12, we also see how the text of the song fits into the model of writing pioneered by the Hebrew poets from Spain. The text plays with the two languages in which it is written and which its intended audience can understand both linguistically and culturally, rendering the phrase from the psalm “yancheni be-ma’aglei tzedek” (lead me in the path of righteousness) more or less as it appears in the original text, but half in English and half in Hebrew; this kind of bilingual, bicultural writing is common not only in the Hebrew poetry of medieval Spain but also in its Hebrew prose, with Arabic linguistic and literary references most common but with instances of Romance language and literary references also not unknown. (More on this below.)

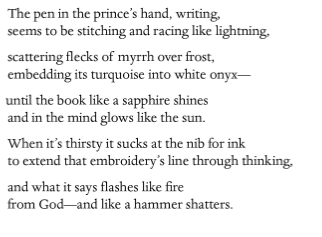

Line 12, “Bless my mind to find rhyme when I write this,” refines the kind of guidance that the poet/songwriter is seeking or expecting from God, writing his own role as a poet into the poem. This is a trope that we see frequently in medieval Hebrew poetry. Samuel ibn Naghrila famously declared himself to be “the David of my age!” Solomon ibn Gabirol called himself “prince to the poem” and began a poetic prologue to a grammar book with the following three lines: “A poem of glory and power I’ll offer my Maker/ who set the heavens on high with His span, because he created the language and mouth of man.” And Moses ibn Ezra wrote an ode to the divine inspiration in his pen:

Finally, the second stanza of Hebro’s song departs from the first stanza’s close hewing to the text and the structure of the psalm; and so all together we can’t think of this as a simple reworking of a biblical text with traditional, medieval Jewish techniques but rather a wholly new composition that quotes from and alludes to text from the Hebrew Bible. These quotes and allusions in medieval poetry, which invoke familiar biblical language and embed them in secular poetry, are called “shibbutzim.” In this case, Psalm 23 is such a familiar text in contemporary American life that a wide audience will understand the allusions in the way that medieval listeners and readers would recognize the full range of biblical material that is found in the Hebrew poetry of Spain.

It might be strange to think of a text so suffused with biblical references as secular poetry, but that’s how this shakes out. As written and as performed, this is not a song for liturgical use; the voice of the poet claims a prophetic rather than a penitential role for itself; and the second stanza in particular is concerned with a historical trajectory.

And, in fact, the most striking borrowing from Psalm 23 has nothing to do with its biblical origins or, directly, with the medieval textual modes that Hebro engages in his song. Instead, it is striking because of the way it is mediated through the history genre of the song itself. It is both a shibbutz and an allusion that grounds the work in its cultural context. This could very well be an obvious observation to people who know the genre better than I do (although I’m not seeing any discussion of it in any popular writing about this song or about the artist’s work) but one of the things that struck me is not just the way in which the song plays with the Hebrew bible in a very medieval mode, but also the ways in which it is directly in conversation with the history of rap music.

I gasped the first time I heard Hebro sing the line (1:41-6): “As I walk through the valley of the shadow of death/gam ki-elech be-gei tzal-mavet.” The allusion to Coolio’s “Gangsta’s Paradise” jumps out: it’s not just the shared borrowing from Psalm 23 but the sampling of the rhythm of the first line of that iconic 90s song that makes the immediate link between the two. And so while I say that it is not directly an engagement with medieval Jewish textual modes, it reflects a kind of common practice: alluding not only the religious texts that the reader or listener would understand but to references from the wider cultural world that they inhabited. Listening to this song and to this sampling in particular, I think it was the first time that I really understood how effective (and perhaps also affective) the full repertoire of borrowing techniques utilized by the medieval poets could be; it was an illustration that helped me come to better understand something that I already thought I knew.

Both the psalmist and Coolio are equally the foundations of this song — it belongs both and equally to the genre of sacro-secular poetry that we see in the Middle Ages and to the genre of rap music. And both are ripe to be sampled from.

***

Coda: A little bit of musical free-association brings me to Leonard Bernstein, and to a version of Psalm 23 that was very much intended for use in a liturgical context: the second movement (3:55-9:45 in the video below) of his Chichester Psalms. I don’t have the musicological vocabulary to be able to talk through it in the same way that I can talk about text (and in fact, someone who does already has — listen to the lecture if only for the reading of Bernstein’s poem on his sabbatical of 1964), but listen to it. Listen to the brass and the percussion lines, especially, where it’s so clear that he was borrowing from himself in little but very distinctive ways. One of my favorite pieces of music, it’s relevant here because it’s another instance of a composer working in this medieval Jewish style: operating in a kind of Davidic mode while remaining very tied to his musical and textual present.