I used to have this friend. For a lot of reasons we grew apart. Ultimately, it was one of those grad school friendships that didn’t survive one and then both of us no longer being in graduate school. I might have tried to hang on longer if I hadn’t felt like I had taken on the role of being the friendly local Jewess whose very being could debunk the kinds of myths believed by people who grow up in parts of the world and the country where they might not have ever met any Jews, and if I hadn’t felt like I was failing at it. She’s the sort of person who thinks she can identify Jews — strangers, classmates, faculty — by the size of our noses or who will start out an anecdote by mentioning that one of the people involved “is Jewish — no offense” as if it were an insult.

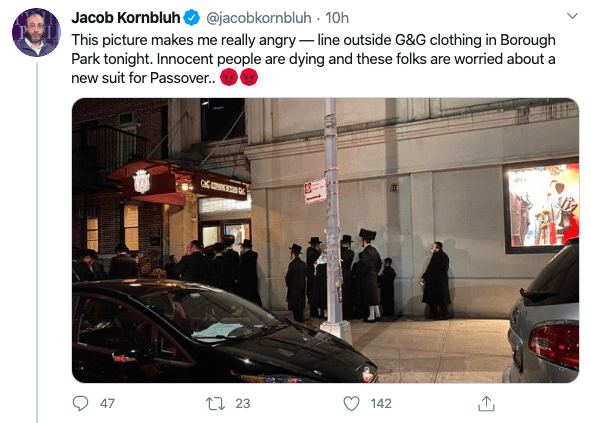

There are other reasons for it, too, but we’re not in touch anymore; and that’s entirely on me. I don’t wish her ill. I hope she’s doing well, whatever well means to her; and I do occasionally look at her social media to see if that’s the case. In the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, a Jewish journalist posting a photo of a line of men in coats and streimels and black hats waiting to buy suits for Passover; the journalist commented that he found this phenomenon infuriating.

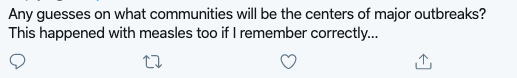

My former friend replied to him:

I’m teaching an introductory lecture course on medieval Spain this semester as part of NYU’s core curriculum, and we are nearing the lecture in which I will discuss the fourteenth-century legends and the rhetoric that grew up around Jews as unique and malicious vectors of the plague, legends and rhetoric that have persisted until today. It’s less flashy than the neo-Nazis who march with tiki torches, afraid that Jews will “replace” them, but it’s still an anti-Jewish myth that has persisted — in forms that change over time, of course — since the Middle Ages.

Let’s start with some statistics. The measles outbreak in Marin County, CA, was the result of a huge percentage of parents refusing to vaccinate their children for non-religious philosophical reasons. The United States was within days of no longer being considered a country where measles is eradicated; we’re not a big enough or spread out enough part of the population at large for that to have happened if measles were a Jewish problem. The bottom line is that yes, there are people in Jewish communities who are wrong on public health issues in ways that perpetuate harm. But there are also people in non-Jewish communities who are wrong on public health issues in ways that perpetuate harm. Thinking that you know better than physicians and epidemiologists or that you don’t have to pay attention to the wider world, whatever the foundation of those beliefs, is not an inherently Jewish trait. People are people in both the wonderful and the deeply stupid ways they engage with the world; but people tend to highlight it and act on it when it’s Jews in the wrong.

Italy is the current world center of the coronavirus. Out of a population of just under 61 million, approximately 40,000 people in Italy are Jewish, or less than one percent of the population. The second largest Jewish community in the country is in Milan, in the north, where the pandemic has hit hardest; that city is home to 12,000 Jews among its 1.4 million residents, an even smaller percentage than in the country at large.

And in the United States, the Hasidic communities where people are lining up to buy unnecessary goods and deliberately cut themselves off from the world ought not be the prime concern. It may well be that there are disease centers in some of those communities, but they won’t be the only communities affected and are less likely to spread it widely around the country and world as are other communities not practicing social distancing, such as spring breakers in Miami, wannabe internet celebrities who are willing to get a communicable disease to own the libs, pranksters with a terrible sense of humor, religious pilgrims of all faiths, large swaths of the American south, and Liberty University.

It may be that Jewish communities will have major outbreaks, but they will not be *the* centers of major outbreaks.

We’ve seen how the tendency to connect the novel coronavirus to China, where it was first identified, is motivated by deeply ingrained existing racism against Chinese people and those of Chinese descent, as well as East Asian people more broadly. That is based on deep-seated prejudices against people of East Asian descent based on incorrect facts and twisted interpretations. Those prejudices have had the most serious consequences in the current moment in terms of an uptick in hate crimes.

But prejudices against Jews, either as hosting centers of disease or as vectors of it, is a close second, based on centuries-old beliefs to that effect. I had thought that as I was nearing the fourteenth-century in my newly online introductory lecture course, I’d write a blog post about the medieval history of all of this. But the fact of the matter is that there’s plenty good been written on the topic, both in the gloriously historical abstract and in response to the current moment. I could write up my lecture for my students, but it’s based on work done by historians of disease and antisemitism like the ones cited below, and there are enough hot takes on this out there already:

Just to get started, check out Maria Guiseppina Muzzarelli’s chapter here on disease tropes in anti-Jewish preaching in medieval Italy, the introduction of Anna Foa’s The Jews of Europe After the Black Death, the Black Death chapter here, the discussion of scattered violence against Jews over plague-related libels in Germany and Poland in chapter five of Living Together, Living Apart, and the epilogue of David Nirenberg’s Communities of Violence.

So I don’t have a great pithy conclusion. I’m not even surprised or outraged anymore that we’re stuck in the fourteenth century in terms of global interfaith relations. I guess this was a lot of words to work out the simple fact that I’m still hurt by the fact that people believe this sort of thing without even thinking about it, and that it’s not other people over there — it’s people to within a degree of separation from me. We can socially distance from the disease itself, but never from this.