I took my sophomores to the Valley of the Fallen this winter following a visit to El Escorial. The purpose of the day was to talk about how imperial ambitions are constructed through art and architecture across time, and the pairing of those two monuments is a great illustration of the phenomenon. Franco was consciously mirroring the location, style, materials, and design of King Philip II’s palace when he commissioned his mausoleum-monument that would ultimately be built by prisoners of war.

Our visit was less than two months after the disinterment of Francisco Franco, and so I also wanted to show the students the ways that the conversation about historical memory is slowly starting to shift. Photography isn’t permitted inside the monument and there were three guards assigned to our group (because we were being led by Francisco Ferrándiz, an anthropologist whose progressive views and activism are unpalatable to the staff there) so I couldn’t take even a surreptitious photo of the shiny, new, blank marble slab with nothing below it. (The surveillance aspect of the visit was striking, both to me and to the students in the group, who were very cognizant of being closely observed.)

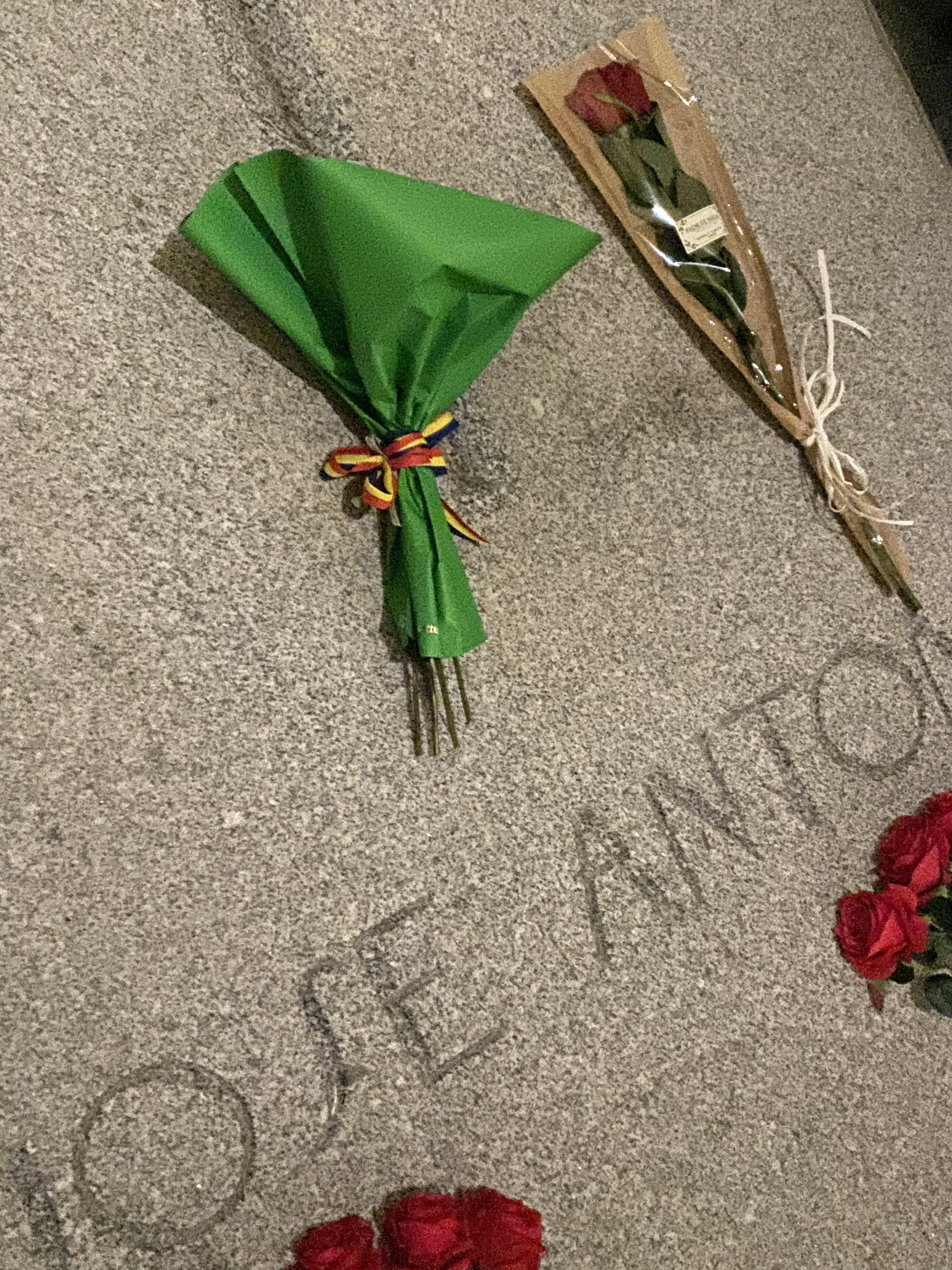

People still venerate the grave of José Antonio Primo de Rivera, founder of the Spanish Falange, whose body will eventually be moved into an anonymous grave on the site along with other people who were killed in the Civil War. I don’t need to digress into a tangent about my willingness or not to sidestep certain rules, but what I don’t feel bound to observe, for sure, are rules designed to preserve nostalgia for fascism; and the one surreptitious photo I did manage to take was of Primo de Rivera’s tomb — in low light and shot quite literally from the hip while trying to keep 28 19-year-olds from wandering off — specifically so I could query one particular detail at a later date: The ribbon around one bunch of roses left by a mourner is in the colors of the flag of the republic: red, yellow, and purple. I still don’t know the answer to the question why, but I like to think that some contrarian florist knew the destination of the bouquet and adorned it with the flag of Spain’s second republic, the democratic government that fell at the end of the Spanish Civil War, and of the republican government in exile.

It’s hard not to wonder and worry about the state of democracy right now with lots of proposals being floated for managing the coronavirus that seem likely to put privacy, civil rights, and even the upcoming elections at risk. So it’s worth taking a step back to celebrate the survival of even fragile, new republics, and the contrarian florist-citizens who insist upon their survival.