Disability studies is another area where I really don’t work at all. This is a book that has been on my to-read list for a long time; I should really get on it.

Disability studies is another area where I really don’t work at all. This is a book that has been on my to-read list for a long time; I should really get on it.

This is a photo I took in February, 2015, of the Alhambra from a vantage point across the Darro River valley in the Plaza de San Nicolás. By virtue of being there in the winter and seeing the fog and the evergreen trees, it really clarified for me why the 16thC churchmen and conquistadores could feel so at home in Northern California.

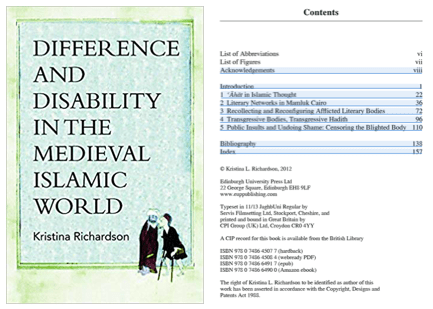

My favorite part of teaching is being the faculty advisor to a cohort of sophomores in the Presidential Honors Scholars program at NYU; we teach students research skills to prepare them to write their senior honors theses, expose them to the cultural offerings of New York City (opera, museums, etc.), and travel with them for a week in January to one of the cities where NYU has a site; the place is so much more teachable in person than in photos and lectures and it’s very rewarding to see the kinds of connections that students make to the material by being on site. (Photo credit: Noelle Marchetta)

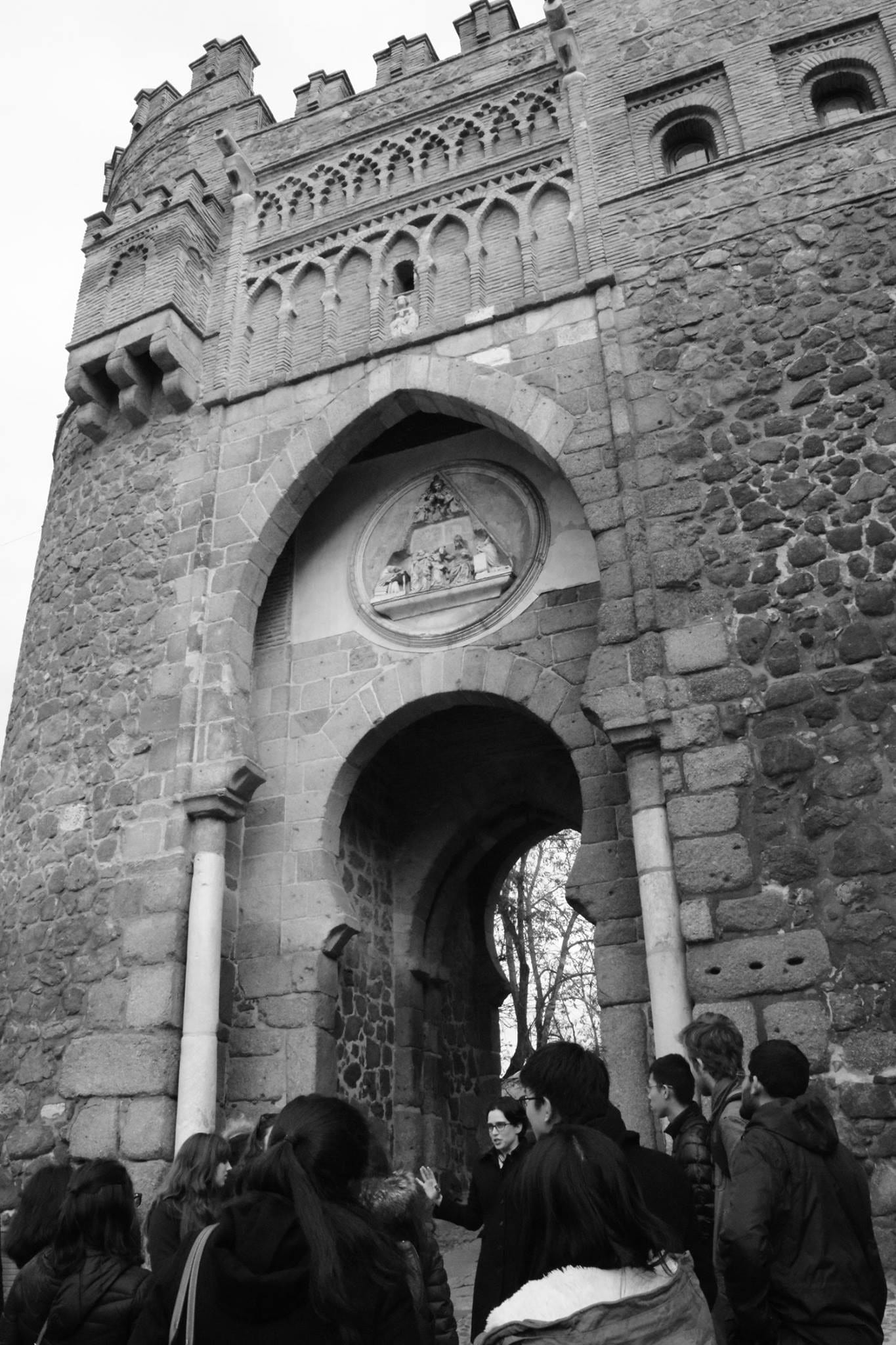

It may be the easy way out, but I’m resorting to a screen grab of text in a word file as today’s photo…

It may be the easy way out, but I’m resorting to a screen grab of text in a word file as today’s photo…

One of the notable outbreaks of violence in medieval Spain came as the part of an incident known as the Córdoba martyrs’ crisis, in which a group of young Christians, unhappy about the acculturation of their peers and egged on by a powerful older cleric, sought martyrdom by repeatedly engaging in public blasphemy and refusing to backtrack when given the opportunity to do so. The martyrs’ lives are recorded in a hagiography by the cleric, Eulogius, who was himself ultimately martyred, too. There’s a new edition of Eulogius’ writings about to be published, edited by Kenneth Baxter Wolf, who also wrote a short account of the episode.

The screengrab that is my main picture for today is from a footnote in a forthcoming review essay I wrote about Geraldine Heng’s The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages, a book which has been received hagiographically, in the colloquial sense of the word, by my colleagues in medieval English literature. From my academic perspective it has a lot of problems; embodied in her treatment of the Córdoba martyrs’ crisis are her tendency to impose modern, popular views of Islam back onto the medieval period and her treatment of non-English materials without the appropriate context in terms of how non-English communities understood and talked about creating and managing racial difference.

The screengrab that is my main picture for today is from a footnote in a forthcoming review essay I wrote about Geraldine Heng’s The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages, a book which has been received hagiographically, in the colloquial sense of the word, by my colleagues in medieval English literature. From my academic perspective it has a lot of problems; embodied in her treatment of the Córdoba martyrs’ crisis are her tendency to impose modern, popular views of Islam back onto the medieval period and her treatment of non-English materials without the appropriate context in terms of how non-English communities understood and talked about creating and managing racial difference.

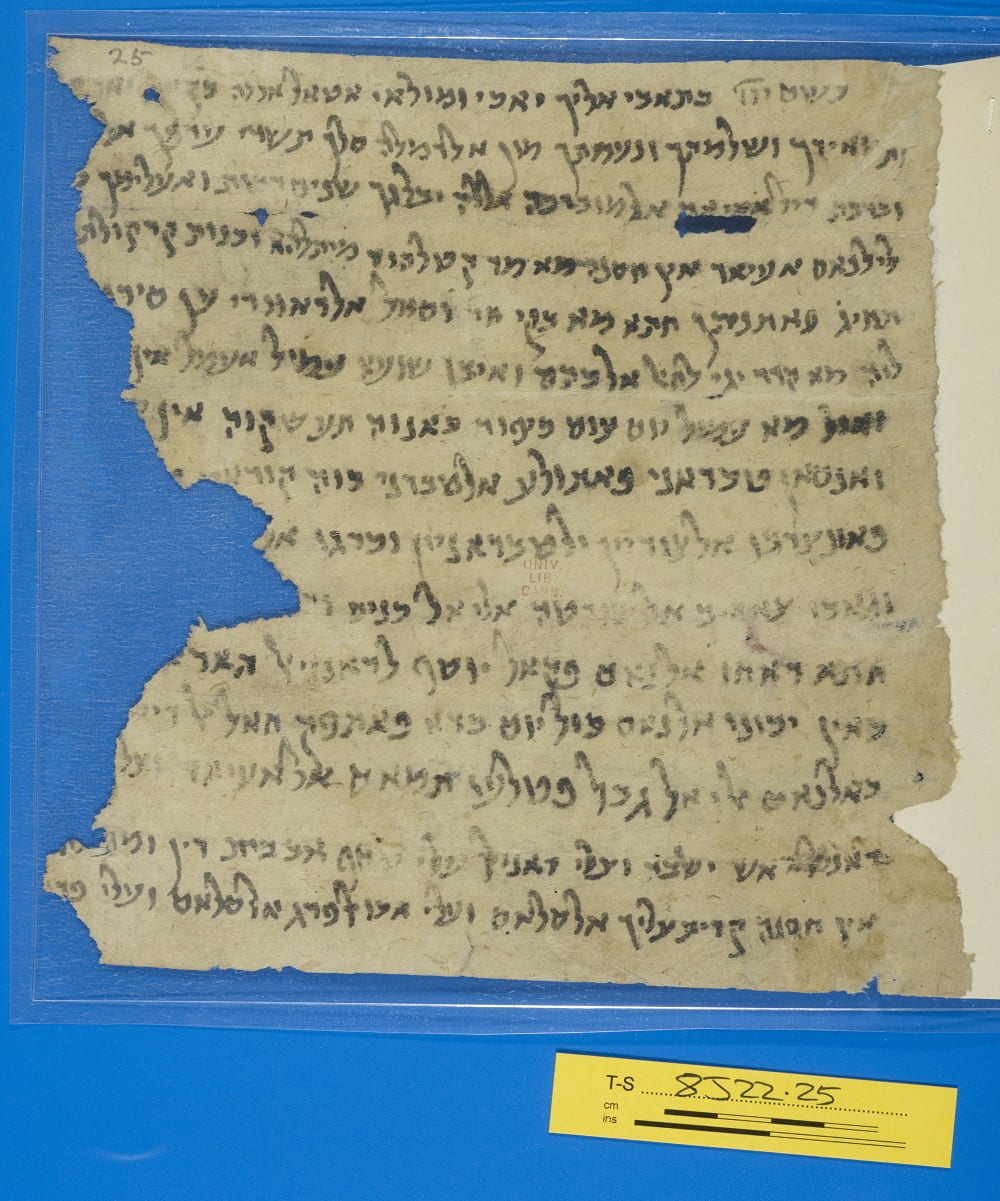

This is a document from the Cairo Genizah that describes a relationship between two gay men in Fatimid Palestine and the social and legal consequences of that relationship. This isn’t an area about which I am particularly knowledgeable, so I’m going to direct you to the Cambridge University Library’s “Fragment of the Month” web feature, where scholars write about documents before they feel like they have enough material for an article. The feature about this document can be found here.

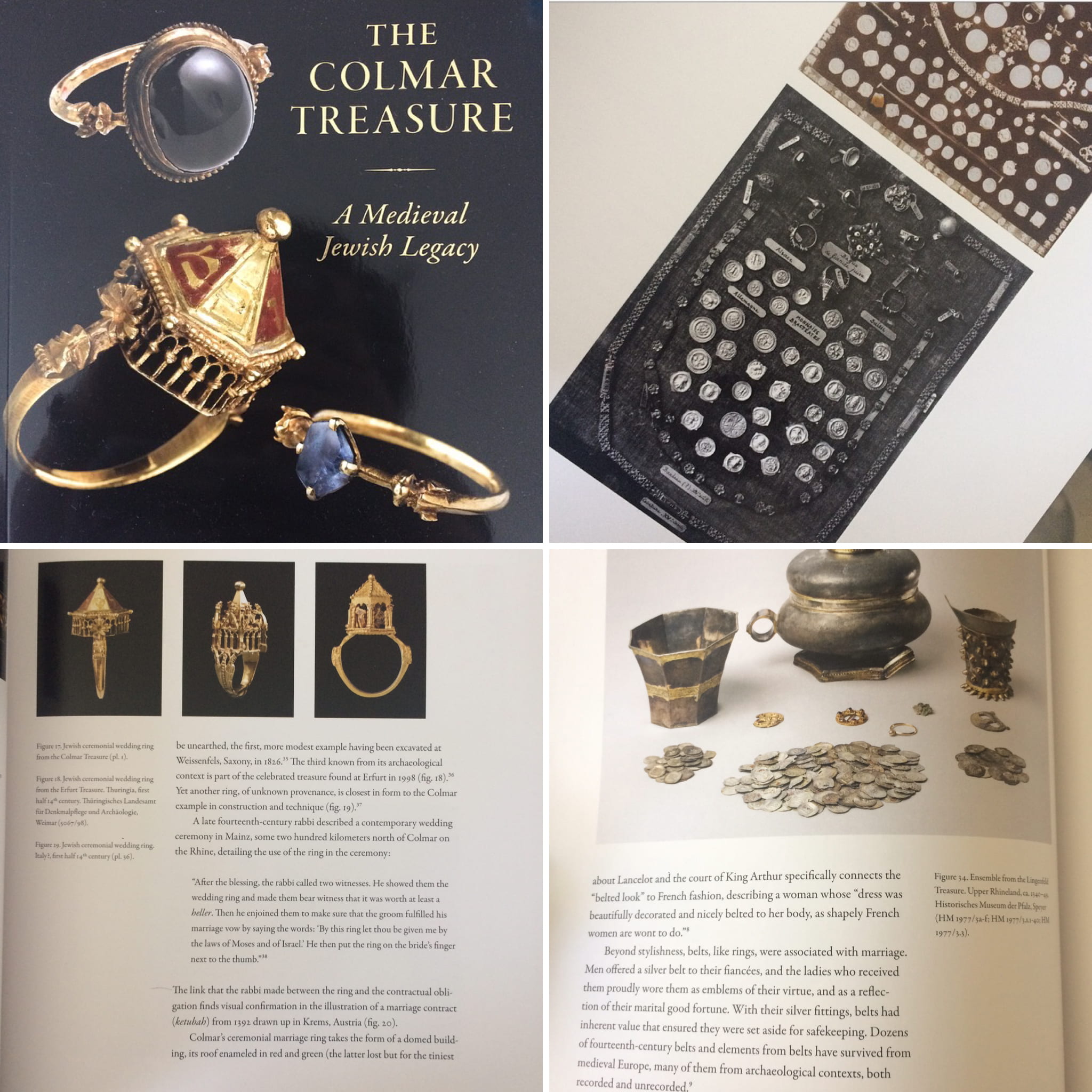

These are images from the catalogue for the new exhibition at the Cloisters of a horde of 14th-century Franco-Jewish jewelry and other metalwork on loan from the Cluny. It’s material evidence of Jewish life in the town of Colmar and the material consequences not only of the Plague but also the accusations that followed around Jews and Muslims about causing the disease. The horde was buried in the floor in advance of the arrival of the Plague and the patriarch of the family was ultimately accused of causing it.

I had hoped to go up today and take some of my own pictures for this blog post because I haven’t seen the exhibition yet, but my own personal material culture (Marie Kondo-ing my apartment as I move back in) is the more pressing matter.

My current book project is a medievalist one, so I could share a zillion pictures for this topic and go in a thousand different directions; but I really like this photo, so I’ll go with it. It’s a picture that I took in the Cloisters during the Costume Institute’s Heavenly Bodies exhibition in 2018. The Cloisters itself is a medievalist building, made up of parts of medieval European buildings brought to New York and reassembled to create a modern image of a medieval cloister. The exhibition was made up of haute couture that draws upon both medieval and modern religious garb for inspiration.

Most of my public scholarship (of which I’m hoping do to an increasing amount in future years) takes a written form and so isn’t super conducive to photographs; but here’s a selfie of me recording an interview for an episode of a podcast, which I wanted to do in order to be able to share my work with a general public. My episode of the Frankely Judaic podcast can be found here: https://soundcloud.com/user-780716487/s-j-pearce-in-the-taifa-kingdoms-the-medieval-poetics-of-modern-nationalism; my colleagues in my cohort also recorded episodes, which can be found here: https://lsa.umich.edu/judaic/resources/frankely-judaic-podcasts.html.

This character is an ñ. This particular ñ is a sign above a restaurant in Inwood, a neighborhood at the very northern end of Manhattan. Phonetically, the sound that it produces is represented as /ɲ/. The grapheme (symbol, character) entered Spanish in the thirteenth century, as part of the orthographic reforms of Alfonso X, known as the Wise. Manuscript evidence suggests that it represented a transformation of an earlier representation of that sound as nn, next to each other, to nn, one stacked on top of the other — a space-saving measure followed by the shrinkage of the top n into a ~. (Still unpacking post-move, and all my history-of-the-language teaching materials are still in a box somewhere, otherwise I’d find a couple of good manuscript images where this happens…)

This one’s a bit more personal and a bit less medieval, but I’m very fond of the photograph: There are a lot of Romance languages (Catalan, Castilian, Venetian, Bolognese, and standard Italian) implicated in this scene which portrays a medievalist with whom I once had a romance, communing with the art in the very-late-medieval mansion of the Romantic painter Mariano Fortuny.