This is the point at which I got stuck on the Lone Medievalist Challenge. I’m actually writing this on August 27, but will backdate it so that it comes in the correct place in the order of my blog posts. The trouble that I was running into was in that I don’t know that “people of color” is a suitable term to use in the context of medieval Spain; and my explanations were falling short and the images I was choosing to shoehorn into the theme weren’t really doing what I needed them to do in able to facilitate a a post appropriately thoughtful for the subject. So: I’m not in any way saying, as some medievalists do and as my colleagues who work on the subject of race and race-making in the Middle Ages rightly decry, that race wasn’t an applicable category in the medieval period. Rather, what I’m saying is that “people of color” as a term seems to me so bounded by modern, western notions of race that to try to identify a “person of color” in medieval Spain requires, itself, a lot of racial categorization that I don’t think is appropriate for the scholar to take on.

With that said, I’m going to combine my “people of color” post with my “library/collection” post because the former allows me to talk about the latter in the context of modern medievalism.

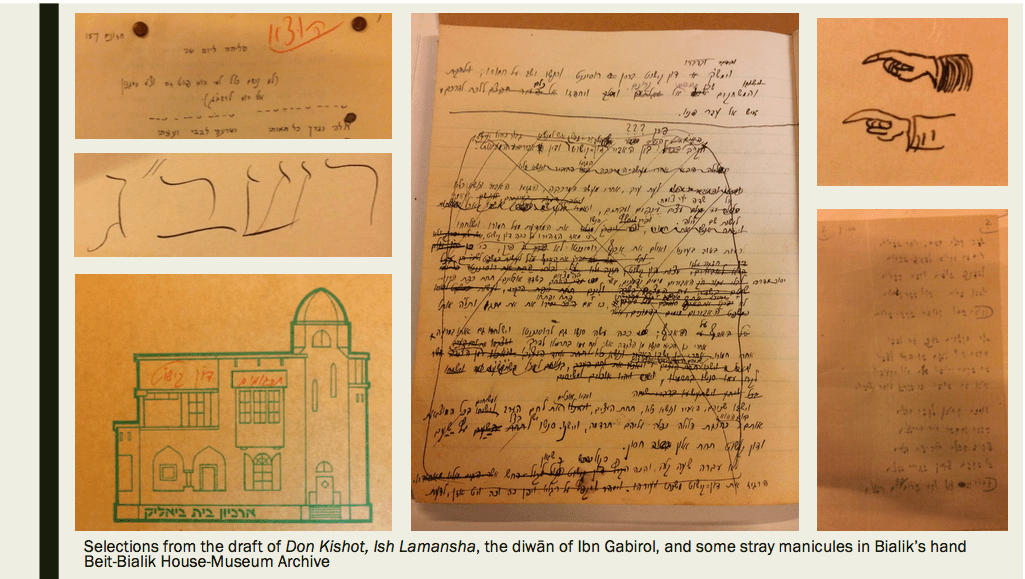

These are some images from the Beit-Bialik house-museum archive, where I spent several weeks last summer looking at Hayim Nahman Bialik’s manuscript draft of his Hebrew translation of Don Quixote and his notes from the time when he was editing the poetic diwan of Solomon ibn Gabirol. But in spite of Bialik’s interest in both the Jews of Spain and utilizing Spanish literature as a way of creating a world literature in Hebrew, he was largely contemptuous of actual Sephardim and Mizrahi Jews. There are two versions of a statement attributed to him, one saying that he hated Sephardim because they reminded him of Arabs and the other asking how he could hate Arabs when they were so like Sephardim; neither version reflects an attitude friendly toward people of color within the Jewish world or the Levant. The archivist of Beit-Bialik sees himself as an absolute defender of Bialik’s reputation; but reading work of scholars like Lital Levi and Sami Chetrit suggests that such a full-throated defense is not warranted.