This is a publicity still from the 1961 film El Cid. This post was originally the introduction to a chapter I’m writing about alt-right rhetoric in contemporary medieval historiography; it was too long and too much of a digression so I cut it from there and am using it to talk about how the epic poem, the Cantar de Mio Cid, was transformed into a film to support the fascist dictatorship in 20th-century Spain.

The scene is familiar: Mounted cavaliers in plate armor hold high their battle standards, festooned with lions and castles, as they mount a siege against the Spanish city of Valencia. Ultimately, they succeed through pure military might and the grace of God and St. James the Moorslayer, claiming a victory for nationalist forces that sought to create a monolithic and exemplary Spanish culture purged of all racial, religious, and ideological impurity. This particular siege, though, was a symbolic victory in every possible way. Valencia fell on 18 February 18, 1961, to Charlton Heston and hundreds of Spanish soldiers who had been conscripted as extras in the Hollywood biopic El Cid, directed by Anthony Mann. Starring Heston and Sofia Loren, El Cid tells the story of Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, the 11th-century soldier who served various kings and led various multiple armies during his lifetime, ultimately becoming a powerful source of national mythology after his death. The movie was a pet project of the fascist dictator Francisco Franco and both relied upon and distorted the scholarship of the prominent medieval philologist and director of the National Library of Spain, Ramón Menéndez Pidal, who was himself a partisan of Franco’s Falangist movement. The movie served to bolster Franco’s claims to hegemonic Castilian leadership by portraying the national warrior-hero anachronistically as a Crusader fighting to “reconquer” territory seized by Muslims in the 8th century in the service of a nascent Castilian state that Franco would, in the fullness of time, lead, sometimes even being depicted as the Cid himself.

In 1987, the then-future prime minster of Spain who himself rose through the ranks of the Spanish Falangist parties, José María Aznar, was asked to participate in a regular feature of the newspaper El Pais’ weekly magazine in which newsmakers dressed up as the figure from Spanish history who mattered most to them and then gave an interview and sat for a photo shoot in costume; Aznar dressed up as the Cid and lauded his country’s historical “crusading values.” In that interview, he made an explicit connection between contemporary Spanish politics and a Crusading vision of medieval Spanish history: “Es que valor de cruzado o espíritu medieval sobra en la vida política, y merma, entre otros sentidos, ese que llama común.” In this observation, Aznar combines the Crusades with territorial battles that took place in the high Middle Ages in what is today Spain, which are often but incorrectly called the “Reconquest.” The idea of a Reconquest implies that territory is being reoncquered, even though contemporaneous historical observers did not see Christian armies of the 8th-11thth centuries as heirs to the Visigoths, the Christian population that had been vanquished by the Umayyad armies of the 8th century; even though medieval battles in Spain frequently did not unfold along religious lines but instead saw Christians battling Christians, and seeking allies amongst their Muslim neighbors in order to defend economic and petty territorial claims; and even though the Castilian Christians who are credited with completing the Reconquest, the 15th-century Catholic Monarchs, Isabel and Fernando, practiced a religion and a culture that would have been unrecognizable to the original conquered population. Historians no longer adhere to this model for these reasons. Yet it is still accepted in popular discourse, especially by people who have an interest in portraying the Middle Ages as a period of religious warfare. Furthermore, there was a single Crusade battle that took place in the Iberian peninsula, and it was not the siege of Valencia but rather took place over a hundred years later at Las Navas de Tolosa, near modern-day Jaén. So, all told, the conflation of the Cid and Crusading ideology represents a popular historical fiction that allows individuals to imagine a more decisively Christian past for Spain than ever existed.

Far more recently, Spain’s relatively new far-right political party, Vox, has begun to use images of medieval Spain to promote an agenda that is explicitly anti-immigrant and populist and that winks and nods approvingly at the fascist period of the country’s history. As a part of the electoral campaign that would see Vox win ten seats in the regional government of Andalucía and, as a result, be brought into the ruling right-wing coalition, it ran a short television spot marshaling the idea of a “reconquest” of Spain for the political right beginning in the historically-imagined reconquest prize: the heart of the historic territory of al-Andalus. Santiago Abascal, the head of Vox, also situated the party’s position toward the European Union in terms of reconquest and a Catholic Spain’s fight against Islam: “With this conclusion to a discourse that touched upon a variety of right-wing touchstones, including illegal immigration and traditionalist values, Abascal’s “implication was clear,” write observers Bécquer Seguín and Sebastián Faber: “Yesterday’s Muslim invaders are today’s Middle Eastern and North African refugees and vulnerable migrants.” Both the rhetoric of the Spanish Middle Ages as a period of reconquest culminating in the 1492 fall of the Islamic emirate of Granada and a newly national Spain’s defeat of the Ottoman Empire at Lepanto in 1517 and that rhetoric specifically as it was used during the period of fascist dictatorship still shapes the political discourse of Spain and its current imagination and self-conception of its own past.

Seguín and Faber argue that Spain’s ultra-right wing political never really disappeared after the period of the fascist dictatorship and the return to democracy. One could almost as easily argue that the Middle Ages never really left Spain, either, in that the memory of the country’s medieval past has played an outsized role in fashioning its national identity from the Civil War through the present. Although al-Andalus has been a far more significant trope in Spanish political and cultural discourse — for the obvious reasons of geographical and historical proximity — than it has been in Anglo-American political discourse, as medieval motifs have become more central to alt-right self-presentation in the United States, al-Andalus has taken its place along with Vikings and the knights of English chivalric romances as models of a fantasy, past operating at the cultural, racial, and religious levels. And so, as a political right wing that seeks to limit immigration, racial diversity, and religious and linguistic freedoms finds itself ascendant in the Anglo-American world, here, too, medieval Spain is becoming a politically useful trope and is finding itself subject to the modes of historical thinking and the rhetoric that characterize extreme right discourse in the present moment.

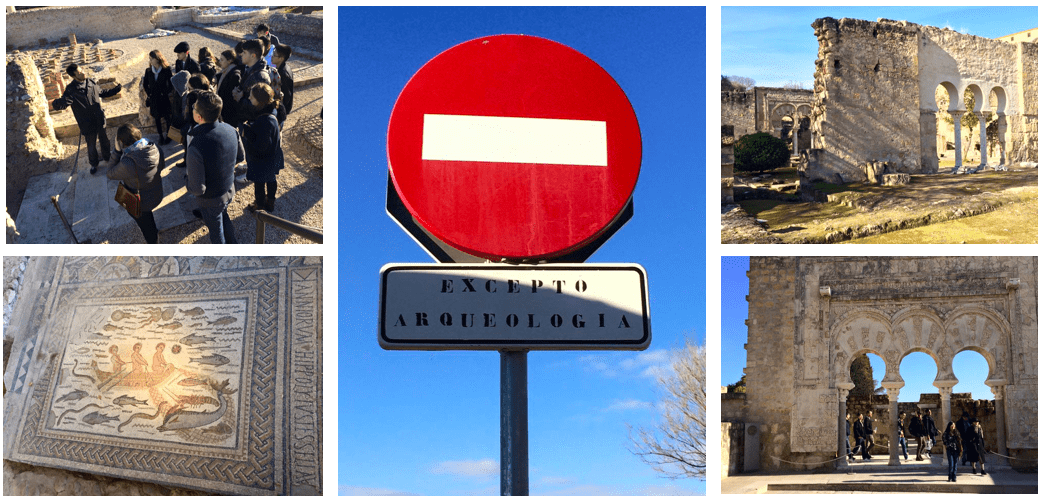

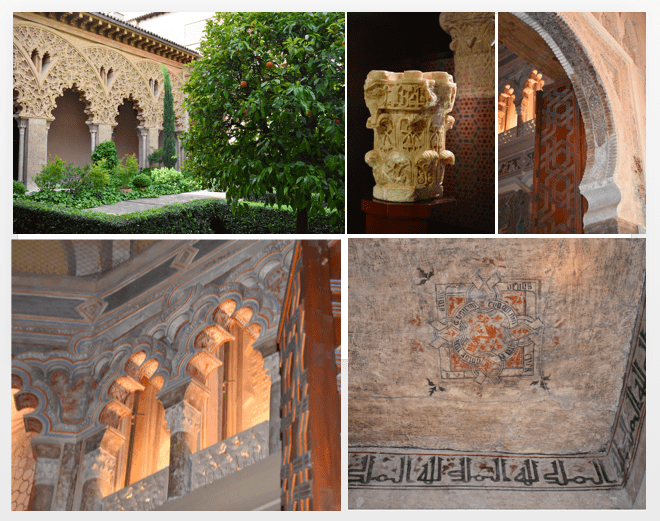

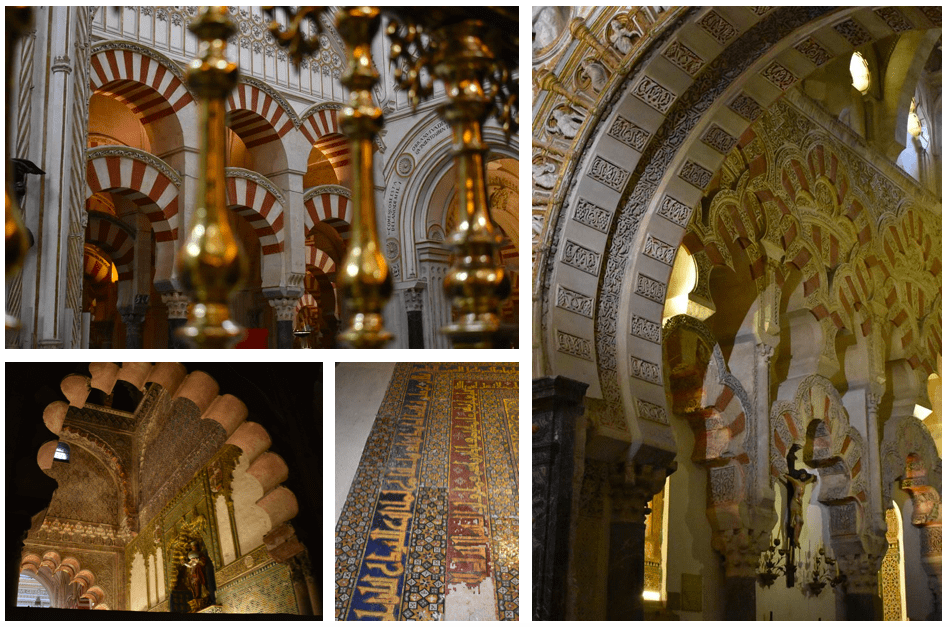

Some views of the Great Mosque of Córdoba, a building that is all modern significance, and always has been. At the moment it was built it signified an attempt to unify a fragmented Muslim community that included military rulers who had been left to do their own thing until the center of power moved west in the middle of the 8th century. It came to symbolize Córdoba during the period of the Umayyad emirate and caliphate, when it became the visual touchstone for al-Andalus (about which the art historian Susana Calvo Capilla has written —

Some views of the Great Mosque of Córdoba, a building that is all modern significance, and always has been. At the moment it was built it signified an attempt to unify a fragmented Muslim community that included military rulers who had been left to do their own thing until the center of power moved west in the middle of the 8th century. It came to symbolize Córdoba during the period of the Umayyad emirate and caliphate, when it became the visual touchstone for al-Andalus (about which the art historian Susana Calvo Capilla has written —