Life’s been pretty non-stop for the last couple of months: I hosted Passover for the first time ever, for ten people. Then I went to Spain for NYU admin stuff. And then I came down with a cold/sinus infection/ear infection the likes of which I have not had since 2013 and which waylaid me for two entire weeks, during which time I had to make do at all kinds of end-of-semester meetings/defenses/receptions. Suffice it to say, not only are my leg and core muscles feeling pretty atrophied, but so are my writing muscles. Since part of the purpose of blogging for me has always been to flex my writing muscles and to get my brain into gear, I’m going to try to ease myself back into work on my book, my translation, and some stray articles, with a bit of a blog post. And maybe I’ll even try one that’s more in paragraph form later in the week.

***

Some of the advice that circulates about writing letters of recommendation has to do with how letter-writers characterize female subjects in ways that might disadvantage them for fellowships, spots in grad school, and jobs, relative to their male counterparts. Does the letter focus on traditionally feminine qualities, such as her capacity to nurture her students rather than her capacity to teach or inspire them? Do you focus on her teaching and his research? Is she a hard worker while he is just plain brilliant? Did you mention how surprised you were that she finished her PhD even though she had twins while in graduate school? (Yes, that last one is a real example from a letter I’ve seen. We didn’t hold it against the candidate.)

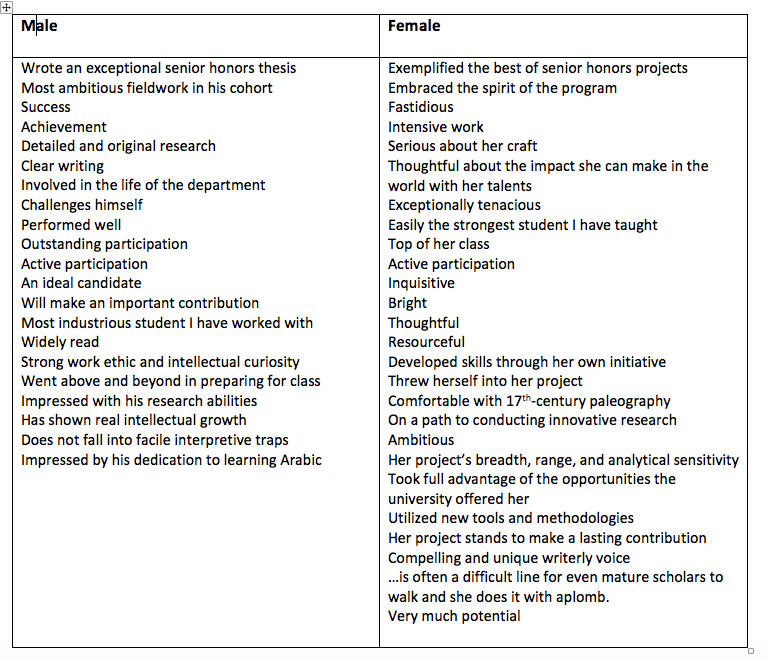

I think I do a pretty good job of avoiding gender bias in my letters of recommendation, but since it’s the season for writing them (not so much for grad students, but for undergrads for summer and post-grad jobs and for honors and awards at graduation) I decided to aggregate the adjectives I used to describe my students and the characteristics/traits/skills that I emphasized, separate them out by gender, and take a look. This semester, I wasn’t writing for any students who identify as nonbinary/genderfluid/genderqueer, so I have a plain binary breakdown:

I talked about the curiosity and ambition of students of both genders, used superlatives in both categories, and talked about class participation for students of both genders. I think based on these lists I have room to make my letters even stronger on students’ behalf, but I think that at least in terms of gender balance, I’m doing okay.

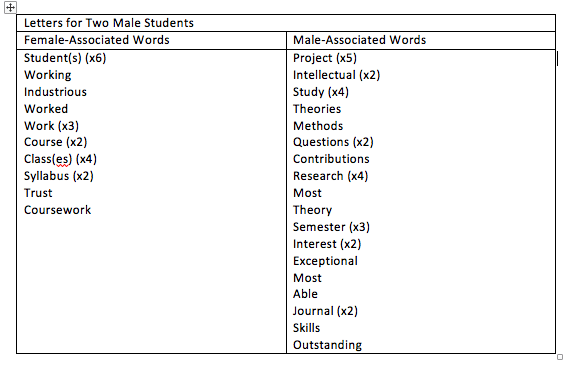

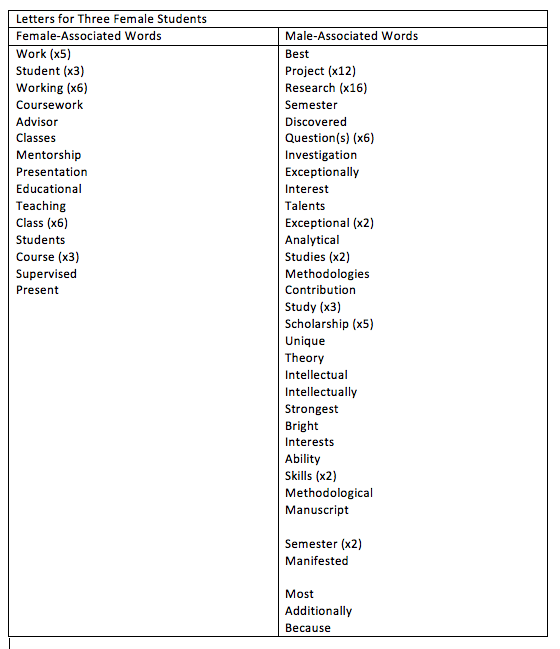

Then I ran the same five letters through the Gender Bias Calculator for letters of recommendation, although I think that ultimately this told me more about the kinds of biases that are most superficial and most prevalent in the academy, and, even more, about the algorithm itself. These were the results:

It’s clear that context matters and that by pulling individual words out of phrases and sentences doesn’t necessarily yield information about bias. I understand that in designating “work” as a female-associated word the program is flagging the possibility of describing female students as hard-workers and male students as naturally brilliant; however, if I refer to a student’s brilliant work on X topic, is that really a female-associated bias? Same with teaching: Just to comment on a student’s teaching doesn’t necessarily mean that I’m flagging female students as nurturers and male students as charismatic, aloof lecturers.

The algorithm also obviously thought that manuscript referred to the manuscript of an article or a book rather than an archival manuscript; otherwise it would have also identified paleography as a male-associated word. What technical skills are male- or female- associated? Is this tool able to assess gender bias in letters that deal in detail with students working on pre-modern topics?

There are some words that registered that seemed almost to border on a gender-equality farce. Including “semester” in the list of male-associated words just makes me think of the feminist law students in Legally Blonde who wanted to change the name of the term to “ovester.” (With that said, I do note that I used the word semester more times in fewer letters for men, so maybe there’s something to that.) And manifest? MANifest?

Also: Because? Because is a male-associated word?

The conclusion I’m drawing from this exercise is (perhaps deadly obviously) that in this kind of assessment, single words aren’t necessarily the most useful way to measure gender bias in letters; context matters and at least for now the human eye and brain can do the job better.