Earlier this year, I was approached by the editor of a small, specialized publication for a general readership who had read my review here of The Myth of the Andalusian Paradise and on that basis asked me to write something for his web magazine. I was thrilled, sent him a little abstract, we agreed on the topic, and I was off. It’s a newish publication and the editor not, as far as I can tell, especially experienced; and by the time he asked me to rewrite the entire thing for the third time, contradicting edits he had made in earlier versions, futzing for the sake of futzing, and trying to make my writerly voice sound like his, I withdrew the piece. He deplored my “lack of commitment to the process,” (that sound you hear is me scoffing, indignantly) and the whole experience left a lot of bad feeling all around. I gather, through the grapevine, that I am not the only person to have had such an experience with this publication. Because it was written specially for a specific publication (and because it’s an approach I don’t really want to take in my own work and writing — looking at medieval history through a lens of anti-Semitism) I’m not sure that I’ll have much success in placing it elsewhere; and on top of that, I’m just not in the mood at the moment to sell myself and my work in the way that one has to do to attract the attention of the editors of general publications. And yet, I have this thing sitting on my hard drive and I wouldn’t mind clearing it from my mental plate. So I’ve decided to share it here. What’s the point of having one’s own web publishing platform if not for that? Plus, I’ve been working on a short blog post that’s related and that I will post by the end of the week, so it’s thematically appropriate for this moment in this space. Plus plus, since I’m already sharing some of the materials that will make up my next book, it fits in that way, too. It’s a long piece (it would have appeared in two parts had it run in the publication that commissioned it) and it’s designed for a general audience, so I hope that lay readers will enjoy it and that the academics who float through here on occasion will see some merit in it, too.

Part I

The Hebrew poets of medieval Spain were the rap and hip-hop artists of their day. In the public performances of their verse, often at the fanciest parties with the finest liquor, they declaimed their opinions on social and political issues that affected them, imbuing their work with their victories and sadnesses; they praised themselves and their skills, caught beef with their peers, and did not let those rivalries die; they sampled the beats of the Arab poets working around them; and they irreversibly altered the properties of the Hebrew language in which they composed. They were complete badasses, they knew it, and they rhymed about it. What they perhaps could never have anticipated was the extent to which their poetry would speak so directly to the concerns of readers who would follow them into the world by a thousand years. But reading with a modern eye, it is immediately clear that many of the struggles that medieval Hebrew poets faced over language choice and national identity — over how to belong — were strikingly modern in their character and they poured out in their strikingly modern verse.

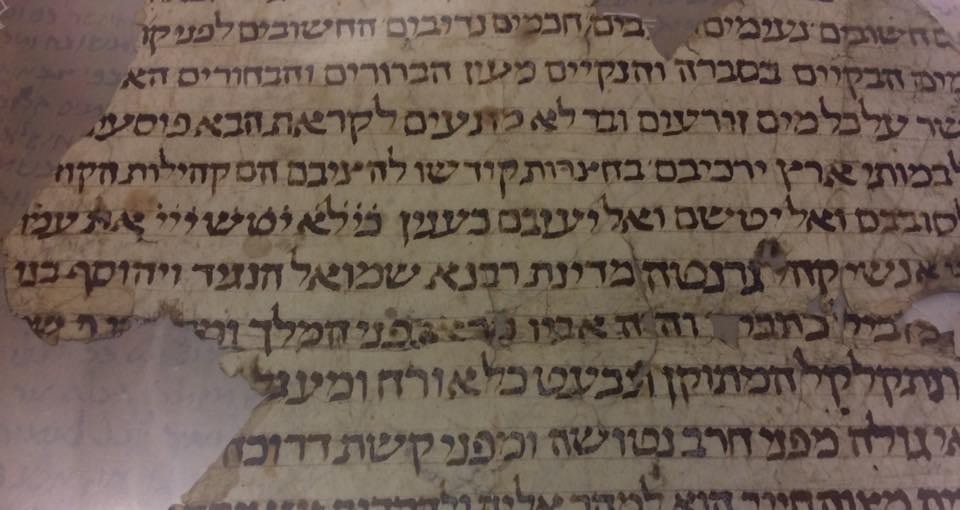

One of these poets was Samuel ibn Naghrīla (d. 1055-6) who served as a vizier and general to the Muslim emir of Granada but was also the leader, or nagid, of that city’s Jewish community and the best of its poets. He earned himself the nickname “twice the vizier” for his military and poetic prowess. His poetry covers topics from fatherhood to the battlefield to the value of both healthy and pleasing foods; some of his most significant poems were written to and about his beloved son Yehosef would succeed him as both the nagid and a government official in Granada. Samuel’s own writings and those that survive that tell his story from others’ perspectives demonstrate that he was deeply engaged with both Jewish and Muslim thinkers and cultural leaders of the day and with their ideas. His poetry is secular in nature but written in what medieval Jews considered to be the divine language — Hebrew — and drew often and strongly on biblical and other religious language, all the while using the rhyme and meter schemes of his Arabic-speaking Muslim counterparts.

Born in the city of Córdoba, the seat of the collapsing caliphate, Ibn Naghrīla relocated to the small kingdom of Granada ruled by ethnic Berber dynasty with origins in North Africa known as the Zirids. Samuel Ibn Naghrīla had served the Zirid emir of Granada Ḥabbūs ibn Bādīs until the latter’s death, at which time Ibn Naghrīla backed the ultimately successful of three candidates to succeed the throne, Ḥabbūs’ son Bādīs ibn Ḥabbūs, and retained his position at court. Among the two who lost out was Bādīs’ cousin, Yaddayir, who remained a thorn in the side of the emirate of Granada. Following his political loss, Yaddayir led troops on behalf of the kingdom of Almería in a battle against Zirid forces led by Samuel at the town of Arjona. Following Samuel’s win, he composed a poem best known to English readers as “The War With Yaddayir.” In that poem the prophetic voice of a victorious general describes the battle to an interlocutor in biblical terms, giving the enemies the names of the biblical enemies of the Israelites:

I trust in the Lord who humbled my foes in snares concealed for my footsteps

when the enemy came to the garrisoned city and slaughtered its vizier like a calf.

He was a foe in the line of my king —

and the evil of strangers pales beside the evil of kin.

Two of the Spanish princes were there, and the Zemarite troops, and they seized the city,

then advanced like a pestilence, destroying the fortress.

Later he describes the conclusion of the battle and the composition of a poem of praise, invoking the names of biblical musicians, poets, and prophets:

My friend, for me in my straits the Rock rose up,

therefore I offer these praises, my poem to the Lord:

He recognized fear of the foe in my heart and erased it.

So my song is sung to the healer: He ravaged my enemies with pain, erasing my own.

Someone objected: Who are you to pay homage?

I am, I answered, the David of my age!

He responded: Is Saul, too, with the prophets? And I told him:

The heir of Merari, Sitri, and Assir, Elkhanah, Mishael, Elzaphan, and Assaf!

How could a poem in my mouth be improper to the God who heals my wound?

(trans. Peter Cole)

The earliest modern readers of this poem argued that this co-identification of medieval Muslim enemies with biblical ones allowed Samuel to consolidate the two parts of his identity: as a Jewish community leader and as the general to a Muslim prince. By, in effect, making the enemies of the Zirids the same as the enemies of the Israelites to whom medieval Jews traced their ancestry, Samuel showed that every military action he took was as much a defense of his Jewish community as of the Islamic state he served and his poetry equally in the models of the biblical poets and his Arab contemporaries.

His poetry shows that the Jews of medieval Spain were full participants in the Arabo-Islamic culture that had grown up there while still remaining devout in their faith; theirs was not a world of fractured identity but rather one that was greater than the sum of its parts. This characteristic emerges not only in instances of cultural flourishing and production, but also in times of tension; in the case of Ibn Naghrīla, even his disputes with intellectual and political foes demonstrate his integral place within the intellectual and social orbits of the place. Both Jewish and Muslim writers left record of their admiration of Samuel ibn Naghrīla, particularly in times and places in which political tensions were low; at such times, the admired leader of the Jewish community could also easily be praised without risk to the political or religious order. For example, the chronicler Sa‘id al-Andalusī placed Ibn Naghrīla at the end of a long line of historically important Jews living in Muslim lands and then wrote: “No-one in al-Andalus before him had such learning in the laws of the Jews and knowledge of how to use it and to defend it.” In other cases, though, writers felt the need to make perfunctory negative comments about Samuel as a Jew before going on to praise him, or even to criticize him in such a way that the praise was subtle and only visible to people very familiar with the genre of writing. One medieval historian described Samuel as “cursed” and noted that “God did not inform him of the right religion” before going on to praise his patience, temperament, knowledge, and even his library and the education he provided to his son Joseph. The cultural historian Ross Brann describes this description of Samuel as showing him to be “less a Jew than a Jew inscribed in the text, an emblem of an idealized dhimmī who is a Muslim in all but name.” In other words, Samuel’s Jewishness functions as a kind of literary device without the author or reader focusing on him, individually, as a Jew.

Medieval Spain is sometimes called a “first-rate place” in the sense that F. Scott Fitzgerald used when he wrote that “the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.” That is to say, the history and culture of medieval Spain is always two things at once — Hebrew and Arabic, Jewish and Muslim, sacred and secular, poet and general, praise and curse — and even if those things seem contradictory to our modern eyes, the Spain of the Middle Ages was a place that allowed them to flourish together as one.

Not all polemics and political disagreements were so polite or couched in terms of mutual respect. Samuel’s son Yehosef was the light of his life, and some of his most famous poems were written to or about him, such as this poem, which Samuel wrote to Yehosef from the battlefield:

Heart’s grief like sharp arrows — through me as never before,

though we’d met no resistance; then why this sorry?

I thought of Yehosef, my faithful, in my heart a continual wound,

for hearts understand what comes to their love across distance…

…Your illness disperses my sleep while others are resting,

and draws me away from tactics and law,

from briefings, and leading the people.

I’m sick with the service of kings who are ready only for war,

and life for a letter from your right hand, with news of your cure.

(trans. Peter Cole)

But love and concern for Yehosef was far from universal. As an adult, he became the tax collector for the Zirid state and carried out his duties with a heavy hand. His tactics as tax collector prompted reactions against him that ultimately led to a riot and massacre of between 300 and 400 Jews in the year 1066. Just as earlier polemicists had done with his father, Yehosef’s Jewishness was criticized as an attribute. In Islamicate chronicles and other literary texts that describe his actions, Yehosef was often referred to in disgust at “the Jew!” This centralizes the idea of Yehosef’s Jewishness as a negative characteristic and is not vitiated by subsequent praise. Unlike his father, who was criticized pro forma for being Jewish by Muslim writers who otherwise respected him, Yehosef’s Jewishness is portrayed as one of many negative characteristics.

Although modern readers might understand both of these types of criticisms of Samuel and Yehosef as being anti-Semitic, the picture is somewhat more complicated than that. Scholarship accepts that there is a distinction between anti-Semitism and anti-Judaism: While anti-Semitism is a hatred of Jews as an inferior race, anti-Judaism treats Jews as a kind of metaphor for undesirable characteristics. It is a subtle distinction but an important one; in the latter case hatred is an excuse while in the former it is the cause. Although different in character, antagonistic writing against both Samuel and Yehosef represents anti-Jewish rather than anti-Semitic rhetoric because it takes negative traits stereotypically associated with Jews (such as greed and profiteering from monetary transactions) and uses them to condemn a disliked individual rather than beginning from a position of hatred towards Jews as a lesser race. Despite this difference in types of antagonistic rhetoric — and despite the clearly anti-Jewish, rather than anti-Semitic, character of these writings — modern representations of Samuel ibn Naghrīla cast him as a victim of anti-Semitism. In Part 2 of this article, we will see three different ways that modern writers imagined a kind of anti-Semitism into Ibn Naghrīla’s biography and the consequences that has for understanding his life, his work, and the medieval world that he inhabited.

Part II

The medieval warrior-poet Samuel ibn Naghrīla is a fascinating character for modern readers, with different aspects of his widely varied biography and writing appealing to different modern audiences. Modern writers, too, see him as vessel through which to explore questions of the modern world, from the bellicose to the literary, and frequently not with an interest in the medieval per se. In fact, in spite of the presence of anti-Judaism in the eleventh-century Granada of Samuel ibn Naghrīla, a common thread that runs through the many diverse modern reinterpretations of his world is one that casts it as a harshly anti-Semitic world rather than one with some manifestations of anti-Jewish thinking, racializing Samuel in ways that the sources tell us he was not racialized in his lifetime and removing him from a universe that he inhabited fully. These modern reinterpretations of the “anti-Semitism” faced by Samuel ibn Naghrīla tell us less about the world in which he lived and more about the world in which these works are created. Modern concerns such as anti-Semitism, nationalism, and even who gets the final say in what material is shared on the internet, are all articulated through accounts of the life of this figure, allowing him to a certain kind of say in a world that he never inhabited.

His (Jewish) Nation… and His (Muslim) King

Part of the poetic portfolio of the famed, national-hero Israeli poet Yehudah Amichai is medieval Spain. Through his poetry he channeled the pains and desires of his medieval predecessors — men writing verse in a renewed Hebrew language — and wrote poems that reimagined the remnants of that time and place into modern circumstances. His fascination with medieval Spain is quite explicable: it was the time of greatest innovation in Hebrew poetry before the modern era and it was also a time in which Jewish writers used their craft in part to assert their place as participants in a world that was fully their own but also never quite so.

Amichai’s fascination with the poets and other writers of medieval Spain began before he gained renown as a poet and it helped to shape his poetic voice. He wrote in the voices of Judah Halevi and Solomon ibn Gabirol, riffed on the travelogue of Benjamine of Tudela, and had a sustained engagement with Samuel ibn Naghrīla. Amichai’s most recent biographer, Chana Kronfeld, explains that the fine lines that Ibn Naghrīla walked were what most appealed to Amichai, writing that the “Nagid is for Amichai such a powerful early paragon because, though writing within a traditional Jewish world that Amichai no longer inhabits, he offers a model for textualizing and thus sanctifying the mundane.”

One of the mundane — or at least secular, by our modern estimation — facts of life that he sanctified was that of regular battle against military and political enemies and his role as the Jewish general serving a Muslim emir; his poem “The War with Yaddayir” is emblematic of the complexities of the mundane in Ibn Naghrīla’s life. As noted in part 1 of this article, the poem suggests a melding of the sacred and the secular elements in his life, defending his Muslim employer from the same enemies — both literal and figurative — from which he defended the Jewish community that he led. When the student Amichai wrote the final essay for that poetry seminar in 1952, he adopted the same line of interpretation and, finally, concluded: “Even though the Nagid was the Jewish leader of a non-Jewish army he saw every attack on his king as an attack on his nation…The anti-Semitism of his enemy helped him to connect his Jewish nationalism to his fidelity to the state in that it made the enemies of his (Jewish) nation the same as the enemies of his (Muslim) king.”

The punctuation of this sentence is striking. By setting off the words Muslim and Jewish within parentheses Amichai makes Ibn Naghrīla a member of a religious community and a subject of a king while limiting the distance between the two groups into which he was bound as well as and the distance between those two groups themselves; the religious identifications are mere apostrophe while Ibn Naghrīla’s relationships to his religious community and to his king are central. He sanctifies the mundane by elevating the Zirids to the level of biblical heroes while also sublimating the kinds of differences that this sanctification might otherwise highlight.

But it was not only Ibn Naghrīla’s balancing of the sacred and the secular that caught the young Amichai’s attention; he was also drawn to the reactions that this “sanctifying the mundane” brought upon him from his non-Jewish neighbors. What did it mean for a Jewish poet serving at the pleasure of a Muslim emir to couch his military victories in biblical terms? What did it mean for that Muslim emir and his subjects to have their wins chalked up to a Jewish vision of the same God of Abraham that they all worshiped? Ultimately the question is not these, but this: How do we talk about the answers to these questions in a modern world where the stakes are different and even the terms of debate would not be recognizable to a medieval interlocutor? Amichai quite clearly saw Ibn Naghrīla’s position at a Muslim court within a context of anti-Semitism. As a student and during a period in which Jewish history was given over to the lachrymose, Amichai lacked a full range of vocabulary to explain the nature of the problem; but even so, he made the important categorical distinctions clear when he wrote:

“It is interesting that almost without realizing it, or perhaps subconsciously, I began this section on the Nagid’s Judaism with a particular provocation known to every Jew throughout the diaspora and that does have its own umbrella term: Anti-Semitism. This anti-Semitism, as most people know, persists against Jews as a nation and that the flourishing of the national movement of Zionism sought to put to an end; and this ‘anti-Semitism light’ (because from a racial perspective, it cannot correctly be applied to the Nagid) nonetheless had an impact on his frame of mind.”

In this paragraph he distinguishes between anti-Semitism and what he calls “anti-Semitism light,” or what we now call anti-Judaism. One kind of hatred is racial and personal, while the other is figural: the Jew is a vessel for undesirable characteristics rather than undesirable because he is a Jew. By reinforcing this distinction, Amichai demonstrates his appreciation that when Samuel came under criticism that invoked his Jewish faith, it was a way of attributing certain characteristics to him rather than dehumanizing him as an opponent.

Amichai’s reading of Ibn Naghrīla’s biography and his position at court shows the sensitivity of a poet. Self-reflective, it takes the medieval materials on their own terms and considers their impact within their original context as well as for the modern world and its literary responses to the Middle Ages. But not every one of the modern readers who are attracted to Ibn Naghrīla reimagine his biography or the circumstances under which he wrote and fought with a similar eye toward the medieval. Instead, other modern representations of Ibn Naghrīla tend toward exaggerating the possibility of anti-Semitism at the Zirid court and portraying it in a way that comes not from eleventh-century Spanish history but rather from twentieth-century German and general imperial history.

Medieval Jewish Comic Book Superheroes

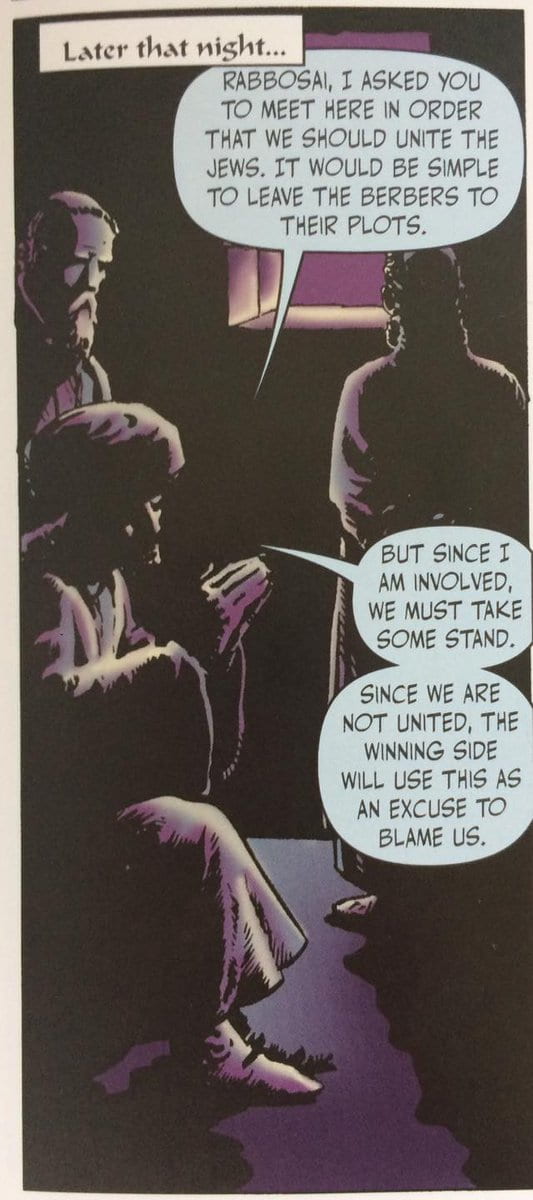

In 2005 Mahrwood Press, whose niche is books designed for an audience of Orthodox Jewish children, published Rabbeinu Shmuel Hanagid, a graphic novel biography of Samuel ibn Naghrīla. This is one of the graphic novel biographies that the press published that render medieval Jewish thinkers —including Moses Maimonides and Solomon Yizhaki (better known as Rashi) — as a kind of superhero: They may not wear capes, but they do have superpowers: defending the weak, standing their ground, studying brilliantly but not too innovatively, and espousing a firm moral code [Image 2].

Rabbenu Shmuel Hanagid is a fictionalized biography based upon the life of Samuel ibn Naghrīla and follows him through his child in Córdoba, his politically-driven flight to Granada, his familial trials and tribulations and his political and military ascent. He is acknowledged as a poet but this aspect of his life is portrayed as secondary to his role as a political functionary. This graphic novel is typical as a cultural product written by and for Jews of central European descent (Ashkenazi Jews) that appropriates the culture of the Jews of Spain and their descendants (Sefardi Jews). Beginning in the 19th century, German Jews in particular began to view the world of medieval Sefardi Jews as an ideal to which they could aspire and incorporated many of their literary and aesthetic practices into the Ashkenazi world. Through this appropriation, Ashkenazi Jewry creates a new Sefardi-inflected Ashkenazi literary, artistic and intellectual culture that still never manages to fully escape its central European, Yiddish roots. This incomplete appropriation undergirds the way that Rabbenu Shmuel Hanagid portrays the life of Jews and Muslims at the Zirid court of Granada. By placing Ibn Naghrīla in an Ashkenazi version of Sefarad (Spain), the book opens the door to kinds of anti-Semitism that grew up in Ashkenaz (central Europe) in the twentieth centry and did not exist in medieval Granada.

The most explicit way in which Samuel is portrayed as a still-Ashkenazi Sefardi hero is through his language. Rather than Standard English his character speaks Jewish English, identified by sociolinguists as a religiolect that has a distinctive cadence, Hebrew and Yiddish loan words, and strong influences from Yiddish grammar: it is a language of Anglophone Jews of Ashkenazi descent. One example of Jewish English comes when comic book Samuel tries to unite his community, he opens his discourse by saying: “Rabbosai, I asked you to meet here in order that we should unite the Jews” [Image 3]. This sentence reflects Yiddish syntax (“in order that we should”) and Yiddish pronunciation of a Hebrew word (rabbosai in place of rabbotai for “gentlemen”). It also uses that Hebrew word, rabbotai/sai, to greet people at the beginning of a meeting; the use of Hebrew greetings in an otherwise English-language setting is also a feature of Jewish English. The language of this graphic novel is not a neutral standard English, nor does it reflect any aspects of the Andalusi Arabic, the Judaeo-Arabic, or the Ibero-Romance, all with Hebrew borrowings where needed, spoken by the historical Jews of Sefarad. Instead, the language of Rabbeinu Shmuel Hanagid serves as linguistic reinforcement of the Ashkenazi roots of the culture that comes to claim Sefardi heroes as its own; it thereby opens the door for the portrayal, in medieval guise, of the kind of interfaith interactions that Ashkenazi Jews might have faced in the 20th century, including those tinged with anti-Semitism, most notably the Holocaust.

The most explicit way in which Samuel is portrayed as a still-Ashkenazi Sefardi hero is through his language. Rather than Standard English his character speaks Jewish English, identified by sociolinguists as a religiolect that has a distinctive cadence, Hebrew and Yiddish loan words, and strong influences from Yiddish grammar: it is a language of Anglophone Jews of Ashkenazi descent. One example of Jewish English comes when comic book Samuel tries to unite his community, he opens his discourse by saying: “Rabbosai, I asked you to meet here in order that we should unite the Jews” [Image 3]. This sentence reflects Yiddish syntax (“in order that we should”) and Yiddish pronunciation of a Hebrew word (rabbosai in place of rabbotai for “gentlemen”). It also uses that Hebrew word, rabbotai/sai, to greet people at the beginning of a meeting; the use of Hebrew greetings in an otherwise English-language setting is also a feature of Jewish English. The language of this graphic novel is not a neutral standard English, nor does it reflect any aspects of the Andalusi Arabic, the Judaeo-Arabic, or the Ibero-Romance, all with Hebrew borrowings where needed, spoken by the historical Jews of Sefarad. Instead, the language of Rabbeinu Shmuel Hanagid serves as linguistic reinforcement of the Ashkenazi roots of the culture that comes to claim Sefardi heroes as its own; it thereby opens the door for the portrayal, in medieval guise, of the kind of interfaith interactions that Ashkenazi Jews might have faced in the 20th century, including those tinged with anti-Semitism, most notably the Holocaust.

In certain instances, the anti-Jewish sentiment of the imagined medieval Islam of comic book Spain is part and parcel of a generalized xenophobia that is portrayed as characterizing Ḥabbūs’, and later Bādīs’, court in Granada and the surrounding kingdoms. During the Middle Ages, non-Arab Muslims such as the Zirids often felt the need to vindicate their lineage and their abilities, especially in Arabic-language composition but in other areas as well, against claims of Arab superiority. The Zirids as they are portrayed in the graphic novel participate in this phenomenon in largely ahistorical ways: by refusing to interact with Arabs and insulting them. But his anti-Arab sentiment expressed at the comic book court of Granada is part of a longer and more complex thread of xenophobia that weaves its way through the book and can be read very clearly in light of the political leanings of its author, Aryeh Mahr.

Although an author’s biography does not determine the value of a literary work nor mandate how it must be read, it is always worth at least noting the cultural and religious context in which a work was composed: During his lifetime, Mahr was a devotee of Meir Kahane, the founder of the Jewish Defense League, a Messianic group that promotes its ideology with violently anti-Arab rhetoric and tactics, including energetically stoking fears of anti-Semitism amongst Ashkenazi Jews specifically to provoke anti-Arab backlash. This authorial context helps to make sense of the skewed and ahistorical portrayal of the Zirid court of Granada that exaggerates its xenophobia and anti-Judaism. The Berber and Jewish figures at court are able to freely express an anti-Arab sentiment that would be perfect at home amongst JDL ideologues while at the same time justifying it by portraying the wider Arab world as one that is dangerous for Jews and requires both Messianic faith and political action [Image 4 and Image 5]. With its setting at a Berber court, the book portrays an Islamic world favorable to Kahane’s anti-Arab vision and casts Samuel ibn Naghrīla as half-victim and half-superhero in it. The xenophobia of the comic book Zirids conveys a lachrymose vision of Jewish history and it also subtly, and to those who know to read for it, promotes the anti-Arab Jewish Defense League. In this vision of the world, Jews may be the victims of anti-Semitism but they won’t go down without a fight; in effect it makes the court of Granada replay the twentieth century as Kahane understood it: the end of the Holocaust giving way to the more complicated situation with Arabs (and Sefardi Jews) in Palestine.

However, in other instances, the anti-Semitism directed at Ibn Naghrīla personally stands out. His political enemies at the court dehumanize him with an odd epithet that was not typically used against the historical Ibn Naghrīla during his lifetime: when they wish to discredit his ideas or policies, they spittingly refer to him as “the Jew!”. Samuel was, indeed, the target of polemical writings by some of his peers in Granada and elsewhere in Islamic Spain. . In other words, this was a shrewd way for polemicists to write to two audiences at once: for the population at large it looked like an attack on a Jew but for the intellectual elite who were familiar with the conventions of the genre, it was a clearer sign of respect and engagement. Instead, the more common association with the epithet “the Jew!” is with Samuel’s beloved son Yehosef, who succeeded him as the nagid of the Jewish community and became the tax collector for the Zirid state. By taking the epithet that was applied to Yehosef in a very specific anti-Jewish context historically and generalizing it to other Jews of the comic book court, including Samuel, Rabbeinu Shmuel Hanagid begins to shift the discourse surrounding Granada’s Jews from an anti-Jewish one to a more general, racialized, and more modern anti-Semitic one in ways that align with the ideology and political leanings of its author.

Medieval Jews and Godwin’s Law

Faced with the image of Samuel ibn Naghrīla as a superhero in a hostile and anti-Semitic world, the average reader might turn to Wikipedia seeking some factual clarity on the matter; but what she will find there is an even more complexly and finely layered tale of modern anti-Semitism portrayed as an eternal problem with clear medieval antecedents (that are, of course, not so clear and not so medieval once the modern ideology supporting them are allowed to fall away), particularly upon navigating to the page about the events of 1066.

Wikipedia’s characterization of the events is made clear from its system of icons and graphics; the 1066 article is connected to the organization’s cycle of articles on anti-Semitism with an icon of a Nazi-era yellow star marked “Jude” [Image 7]. By using an iconic image from one of the most classically anti-Semitic episodes in history, Wikipedia casts the 1066 riots and masscare as purely anti-Semitic, rather than anti-Jewish, and the Ibn Naghrila family as victims of anti-Semitism. Without a broader perspective Wikipedia editors bundle the events of 1066, anti-Jewish in character and inspired by the personal hatred towards a professionally corrupt official, with the anti-Semitic Nuremberg Laws that mandated that Jews wear a yellow star in 1930s Germany; ultimately, by suggesting that the one is related to or a step on the path towards the other, this page does a disservice to that reader who comes looking to better understand the socioreligious context in which Samuel and Yehosef ibn Naghrīla interacted with their peers.

Earlier I described Rabbenu Shmuel Hanagid’s approach to history as “lachrymose”; this is a term and an approach to history-writing that themselves have a broader intellectual context: The Columbia historian Salo Wittmayer Baron identified a trend in his field that he termed “the lachrymose conception” of Jewish history. He was critical of histories of Jewish communities that charted a course from tragedy to tragedy, leading only the next externally-imposed catastrophe and ultimately (although this is a later modification of the idea that Baron first coined 1939) to the Holocaust. In addition to lachrymose historiography, another historical theory comes into play here, one that emerges from an environment more closely related to Wikipedia’s native one: Godwin’s Law is a still-vibrant relic from the early internet days of Usenet message boards. It postulates that the longer that a discussion online goes on, the statistical probability of somebody making an inopportune Nazi analogy approaches 1. The corollary to Godwin’s Law is that the discussant who makes the inappropriate analogy loses the discussion by revealing himself to lack control over the facts of the argument and over his own rhetoric. While the riots and massacre of 1066 were a tragedy they did not represent a holocaust or a genocide and were not motivated by anti-Semitic thinking. The Zirids were not the Nazis. When Salo Baron challenged the lachrymose view that his predecessors took of Jewish history, he urged his peers to escape the then-reigning teleological and pessimistic model of writing Jewish history. He found it to be a dishonest view of history, and one that ghettoized both its subjects and its practitioners. Wikipedia’s editors have put the Ibn Naghrilas back into a ghetto that they never occupied because it never existed; and, on the basis of Godwin’s Law, or more precisely, because of their tenuous grip on the historiography and the big picture, their discussion of the massacre of 1066 is a losing one.

Who Was That Masked Man, Anyway?

With three distinct answers in three different literary works, the reader is justified in continuing to ask: Who was Samuel ibn Naghrīla? And what challenges did he face as a Jewish leader at a Muslim court in a world populated with both friends and foes? Because for all of these three representations, he still seems to be a bit of a caricature, subject, as the poet would have it, to decisions and revisions that a minute could reverse, as the poet would have it. Always full participant and always alien, the two halves of Samuel’s identity become a vessel for modern writers to fill with their own attitudes toward the place of Jews in a wider society.

A non scholar here. You seem to be referring only to jewish poetry in hebrew and in the arabic Spain. What is it known about jewish poetry in arabic, spanish or portuguese in the peninsula? For sure you have the renaissance poetry of Bernadim Ribeiro in portuguese and more literary works by him and others, like Usque. (This besides all the moroccan sephardic tradition in judeo-spanish) .

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oWv8Si0tOfA

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TMSc3FEJHyE

Thank you

Sure, there’s lots known about poetry in other languages. Check out the Cambridge History of Arabic Literature: The Literature of al-Andalus as a starting point: https://books.google.com/books?id=W5JxUjfwInoC&printsec=frontcover&dq=cambridge+history+al-andalus&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiC8ui3_araAhWb3oMKHfa2AxgQ6AEIKTAA#v=onepage&q&f=false