This is the paper that I am slated to give this afternoon at the workshop “After the Conquest: Converging Approaches to the Study of the Iberian Reconquista” at the Woolf Institute, Cambridge. Writing the paper allowed me to begin to think through a new chapter in my current book project; perhaps predictably, by the time I was finished writing the conference paper I had gotten my argument just to the point from which I need to start writing the book chapter version. Even as a first draft of a first draft, this is truncated; I had to cut fully a thousand words from my initial version of the paper in order to keep to time — one of the things I’m looking forward to about this workshop is that we’re giving short papers and each session is followed by a roundtable. It seems like it will be a very productive format. The sets of asterisks mark where I did the most butchery — I’ve saved those passages to put back when I begin to (re)construct the chapter. The state of medieval studies online these days is such that I’d simply say: If you read this and are inclined to shout at me for not including enough examples, for not having a more fully developed theoretical framework, or not having cited the work of your favorite theorist or scholar or medieval chronicler, please consider the possibility that it was there in the extended version and will again be there in the book. (I, myself, was particularly unhappy about consigning the work of Nadia Altschul, Simon Barton, and Ibn Bassam to the file called “cut bits of the cambridge reconquest paper.docx.” I don’t have time before the workshop begins but I’ll add some bibliography later to give a sense of where I’m going with all of this in terms of its situation within the field.) This is a paper that really sets out a methodology rather than offering a full display of what it can do. That will come in the parts of the conference that are invisible to the internet and in the much longer project of book-writing. For that, stay tuned.

As a scholar trained in literary analysis, even as one who practices a very historicizing brand of that kind of work, I often find myself as the odd man out in discussions of history and historiography; as a consequence, I would like to begin my remarks today with an explicit appeal to the initial call for papers for the workshop as a way of arguing for the place of the study of literature as a historiographic methodology. Two of the possible axes of analysis proposed in the framing statement for the workshop particularly caught my attention: 1) Can gender, postcolonialism, and subaltern studies help to nuance the discussion? What are these approaches’ limitations?; and 2) Cultural vs. political/social/economic approaches to the conquest. At the junction of these two axes, I see room to consider a wide range of types of evidence within their cultural contexts and informed or facilitated, but not driven, by contemporary theoretical approaches.*** In other words, rather seeking to simply apply postcolonial or feminist theories to Reconquest texts, an approach that quite often gives misleadingly forced results, I am asking how readers who live in a world itself informed by postcolonialism or feminism view those texts and how their literary and cultural insights into the medieval text might propose a renewed and newly historicizing reading.

The lines along which we draw boundaries of genre or discipline, and the ways in which we define the parameters of history-writing by definition shapes the ways in which we think about the use of literature as a historiographic tool. Although this observation is a bit of a tautology, drawing it out helps us to see the ways in which the disciplinary location of those boundaries has come to shape our epistemologies and methodologies. Our concern here today is rethinking the historiography, the messy boundaries, of the “Reconquista” — and although time does not permit for a fuller discussion of the term and my reservations about it, please understand me to be using that term very much entre comillas — but an instructive parallel case is the debate over the bounds that confine the notion of “convivencia,” another critical term that similarly still generates scholarly debate and fierce partisanship, and sometimes serves to paper over important details and historical mechanisms. Ryan Szpiech has observed that this debate “is in fact the product of unsettled rivalries generated by the shared disciplinary history of philology, historiography and literary criticism, methodological rivalries which at their core have very little to do with medieval Iberia… the ongoing debate over convivencia can be best explained as opposed reactions to the conflict of method in the human sciences in the wake of the linguistic turn” (136). One conclusion that the reader may draw from this observation is that a shift toward literary evidence within the framework of historical investigation (in other words, a challenge to a traditional scholary boundary between literature and history) will necessarily shift not only the terms of the debate but its potentialities; the vision of literary history that is reflected back from this disciplinary collision of criticism, philology, and history, functions productively as what María Rosa Menocal referred to as “Dante’s cult of truth.” To write or to read in that mode, from within that cult, is to take guidance from text about text, not synchronically but synchronistically. And so perhaps, too, we might revisit the notion of historiography from this perspective of literary history — to stand it opposed to political history, etc. and to see what might emerge from a synchronistic, literary-historical reading of a classic moment in what is traditionally considered to be the “Reconquista.”

With the disciplinary and theoretical framework thus established, in this next section of my paper I will set out a case study that demonstrates the possibilities that “Dante’s cult” holds for reassessment of “Reconquista” thinking. It will explore the ways in which a reader-reception model not of literary criticism but of literary history can help to destabilize the regnant scholarly categories that would separate medieval Spanish Christians from their Muslim counterparts and reify their political and military goals as territorial and primarily faith-driven, a model that at once sounds cartoonish but cannot be extricated from the historiography as long as we continue to think about it in terms of conquista and reconquista. My remarks today draw upon material from my current book project, which principally explores the use of the poetry and poetics from medieval Spain in Arabic, Hebrew, and Romance, by 20th-century poets and critics in the service of the modern nationalist conversations and movements that they joined; it also addresses the question of what we as modern scholars mean when we speak of national identity in the medieval period and what, exactly, it means when medieval writers working in a range of languages deploy words that we tend to translate into contemporary English as nation.

One of the chapters in the project focuses upon post-Imperial and post-colonial readings of the medieval epic poem that is perhaps most closely associated with the formation of a kind of modern Spanish identity, that is, the Poema de Mio Cid; this chapter examines the ways in which three modern writers revisit not only the poem but the host of legends and wealth of historical materials that deal with the life of Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, known by the honorific, el Cid, a mercenary warrior who would sack the city of Valencia in 1094 and govern it. Despite a large and persuasive, though not uniform or incontrovertible, body of evidence suggesting that the Cid was not operating in a “Reconquest” mode and was not seen to have been doing so by his contemporaries, the sack of Valencia is an event that is often, and incorrectly, tied to the teleologically-developed idea of a Catholic Reconquest of Islamic lands in the Peninsula. It is out of this kind of reading that the figure of the Cid becomes a proto-Spanish hero, very much in line with the 20th-century dean of the field, Ramón Menéndez Pidal, whose historical analyses were heavily dependent upon the epic Poema de Mio Cid, written two centuries after the fact and with due poetic licnese, and also guided heavily by his program of global hispanismo and of a search for the origins of Castilian national identity, in linguistic as much as in religious and cultural terms. As the field has come to reckon with Menéndez-Pidal’s political and cultural commitments and the ways in which they and his reading of the poem may have been mutually constitutive, the notion of the Poema de Mio Cid as an example of “Reconquest” literature has largely fallen out of favor; nevertheless, the figure of the Cid as he appears in the sum total of literary documents that treat his life as a subject has continued to make its subject a “reconquerer.” This is to say, the many ways in which his life has been committed to writing serve the needs of authors and communities of readers — both contemporary to the Cid and later medieval ones — that benefited from portraying medieval Spain as a place galvanized along religious lines as parties pursued territorial gains, as well as those of authors and readers who portrayed the time and the place in a more realistic, nuanced, and messily-allied way. *

One of the postcolonial rereadings of the life and literature of the Cid through which I hope to propose a renewed approach to those medieval materias is Salman Rushdie’s 1995 novel The Moor’s Last Sigh, one particular passage of which I will use here as a case study to illustrate the possibility of reading the Cid in that “cult of truth.” Very briefly, The Moor’s Last Sigh is the epic familial biography of the Da Gama-Zogoiby family, descendants of Portuguese and Spanish merchants — a motely crew of deviant connivers and piratical businessmen whose identities are constantly in flux in both instrumental and considered ways. The protagonist, nicknamed “Moor,” (an appellation that in and of itself requires its own treatment) is the last scion of the dynasty and finds himself mediating between his mother, a painter, and her artistic rival. The painterly drama, full of ghosts and hexes, is set against a backdrop of increasing Hindu violence against Indian Muslims around the time of independence from the British Empire, which stands as a contrast to the imagined medieval Iberia that is Moor’s ancestral homeland, a place that, he comes to discover, is likewise rent apart by sectarian, fascist, and populist violence in modernity. Beginning with Cidian lore and ending with Don Quijote, this is a text about text; and it offers the reader guidance through those works in the same way that Dante’s Vita nuova guides its reader through the reinvention and medival modernization of Italian literature. I should also just add that I am only at the beginning stages of writing the chapter on a range of modern reuses of the Poema de Mio Cid and other Cidian literature and lore, and so I very much welcome the chance to hear your feedback during the Q&A.

The allusions to the late moments of the Middle Ages in Spain that appear in the book — and especially to the literary textuality of the time and place —are numerous. The title, of course, refers to the image constructed around Boabdil’s 1492 surrender of the keys to the city of of Granada, erstwhile his, to the Castilian monarchs Isabel and Fernando, a moment referred to popularly and historiographically as “the moor’s last sigh.” As just one example from within the text of the novel, Moor’s ancestral village in Spain, Benengeli, found itself at the end of the Spanish Civil War to be locked in perpetual conflict with the town next door, Avellaneda, with a third town, Erasmo, also drawn into the conflict, embodying and giving new life to the conflicts over the real and fictional authorship of Don Quijote and the diffusion of humanistic knowledge in Spain in the age of print. For my part, I like to read this novel — so explicitly in dialogue with the fall of the Nasrid kingdom of Granada in 1492, the fates, literary and historical, of the converts and crypto-Muslims left in its wake, and the fortuitous beginning of the Age of Exploration — instead for its reinvention of an earlier moment: historical memory and literary invention of the Cid. Reading this novel as a Cidian reinterpretation often catches one’s interlocutors off-guard: it is so plainly a novel grounded in the memory of fall of Granada set in the twentieth century on the subcontinent that it can be jarringly illuminating and instructive to draw out the Cidian strains that are present in the book; and for our purposes, to treat The Moor’s Last Sigh as a cipher for the life and legend of the Cid that is not simply informed by postcolonial theory but emerges wholly from a postcolonial literary context allows us to make a more incisive study of medieval Cidian materials that challenges the narratives that emerged from a 20th-century, effectively imperial, desire for a hero of the imagined community of the Spanish nation, narratives that in spite of their evident flaws and the explicit challenges to them, have continued to form a powerful substratum of reading and study.

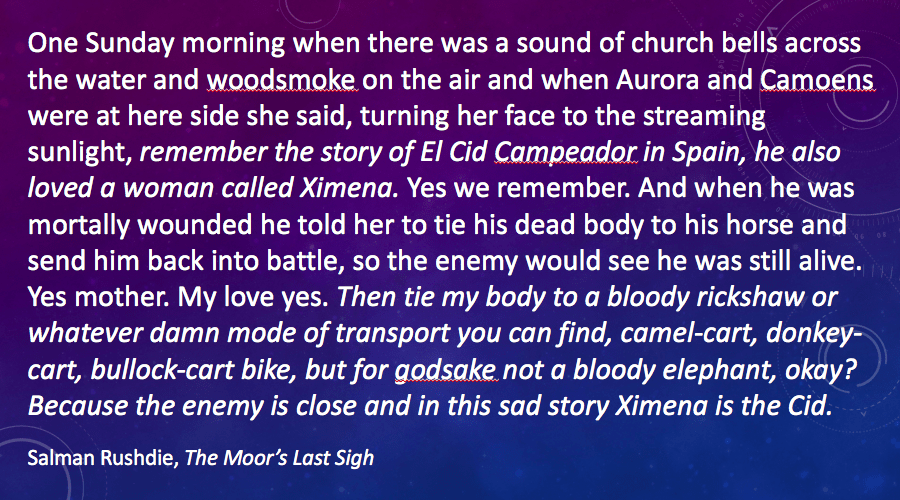

Rushdie’s reading of the various legends of the Cid may not be subtle, all in all, but, if I may be permitted the sort of judgment that we literary critics tend to avoid, it is as sublime as thought-provoking one. The novel as a whole does not treat the history of Spain ahistorically, plucked from a single moment, or as a mere literary or rhetorical device; instead it bookends the Da Gama-Zogoiby family story in between the unremembered memory of two crisis points, two high points in the traditional narrative of the Reconquista: the conquest of Valencia and the fall of Granada and its aftermath. The passage that I am going to present here appears in the first part of the book, which represents the years of the family’s life before the birth of Moor and his sisters; this passage is the deathbed scene of Moor’s grandmother, Isabella Ximena da Gama. When I talk about the novel being bookended between the falls of Valencia and Granada, we need look no further than the name of the family matriarch, a concatenation of the name of the Cid’s wife and of Isabel of Castile, each woman present at the creation of a new vision of nation. Moments before her death, Isabella makes an admonition to her daughter and husband:

Within the novel, this passage serves to highlight Isabella’s importance as matriarch and to cement the spectral relationship of haunting between mother and daughter that is present throughout the novel in a variety of guises. Examining it from the perspective of literary history, it also raises a great many questions that invite a return to the Poema de Mio Cid and other Cidian lore and history.

When reading the novel in its literary historical context, the image of the family matriarch with clarity of conviction orchestrating the circumstances of her own death in the model of a war hero drives the reader to reconsider her assessment of the figure of Ximena in the medieval texts. The final words uttered by Isabella before her death — “Because the enemy is close and in this sad story Ximena is the Cid” — identifies the wife with the heroics of her protagonist husband and forces the reader to ask what it means for Ximena to be the Cid, to take the place of the hero or to be assimilated to him, for a woman to be central in the text and a warrior in the legend, to be transformed from the wife left behind and ransomed into something else entirely. Here we find the novel provoking a revisiting of the medieval Cidian materials, literary, historical, and documentary, from a feminist perspective; it is the figure of Isabella da Gama herself who has opened up that pathway of investigation. We are invited, indeed compelled, to think with Ximena (in the Levi-Straussian sense of the prepositional phrase) as we return to reread and to and reevaluate the Poema and the other Cidian materials.

The novel also presents possibilities for a postcolonial rethinking of the medieval — in effect a coaxing of the literary and historical figures of the Cid out from under Menéndez Pidal’s long shadow and impelling a reconsideration of whether and how that might have looked like a national hero closer to his own time and closer to the way in which he and his fellows might have seen him.** Approaching the Cidian materials as they are already refracted through a literary reading that emerged from a particular and different postcolonial context — in other words, through this reader-reception model of medieval literary history that I am advocating — serves to destabilize the categories and types of knowledge that create the figure of the Cid who fits into a “Reconquest” model and challenges the limits traditionally placed upon the literary and epistemological agency of people who fall far further outside of the proto-nationalist narrative created in the 19th and 20th centuries than that narrative could ever allow.

Returning to the text of the novel and to the very same passage that I cited before— as I mentioned, this is a dense, rich text— also helps to open up this avenue of inquiry. Before using her middle name to identify herself with the hero of the legend of the Cid, Isabella exhorts Aurora and Camoens to “remember the story of El Cid Campeador in Spain” and makes herself the hero by invoking the well-circulated image of the corpse of the Cid, tied to his horse Babieca and sent back into battle as a ruse to convince his Almoravid enemies that the valiant commander was still very much leading the charge and a force to be feared. “Remember the story,” exhorts Isabella, beginning to suggest not a familiarity with text — that is, with the Poema de Mio Cid — but rather with the stories of its hero. “Remember the story…” is how we speak of stories we have heard, that float in the air that we all inhale, rather than the ones that we have read and that have some fixity on the printed page. Isabella lets on that the story of the Cid, in her world, is an oral story. Confirmation that that is the mode of transmission in the world of the novel comes a sentence later, when Isabella invokes the most famous extracanonical image of the body of the Cid tied to his horse; this is an image that appears neither in the poem nor in the chronicles, but is rather accreted to the body of Cidian materials not until the end of the thirteenth century by a monk who sought to portray the Cid in a manner parallel to Baldwin I, king of Crusader Jerusalem (Aberth, 134), thereby enshrining a “Reconquest”-type ideology not within the textual canon but within the later legend of the Cid that was largely transmitted orally rather than in writing. I am omitting a lot of necessary discussion of orality and the Cid in the interest of time, but suffice it to say: The body of the hero, carrying on after he has gone, is part of the legend of the Cid, the oral tradition, those classic things that everyone already knows through a common epistemology not explicitly defined. This stands in contrast to the novel’s regular and clearly textual allusions to Cervantes’ Don Quijote and not to any of the popular abridgements or reimaginations that began to crop up nearly immediately in its wake. Ironically, by invoking perhaps the most popular image of the Cid painted as a hero motivated by a “Reconquest” ideology, the character of Isabella Ximena da Gama pulls the postcolonial Cid away from the text that makes the canonical Cid a part of Spanish national identity. The Cid of the subcontinent of The Moor’s Last Sigh is a local legend, beginning with a late fiction about its subject that masquerades as sacred history and preserved through telling and adaptation from mother to daughter. It eliminates the PMC entirely and puts the figure beyond the reach of Menéndez Pidal’s scholarship and imagination.

This is not to say that the novel never engages with or even upholds what we might call a Crusading view of history, one that encompasses a Reconquista that is a battle of Christians against Muslims. The complex and the messy in this novel, its engagements with and rejections of imperial power serve as a reminder, perhaps in a voice we are more primed to hear because it is more like our own, of the messiness of medieval lives and political commitments and culture that grew up around, because, and in spite of all of it. Rushdie’s Moor is always one thing and its opposite just as the Cid in his represented complexity is a crusading idealist and a pragmatist, a leader of Christians and a leader of Muslims, loyal and treacherous, self-interested and community-minded, a conquerer, a reconquerer and a mercenary.

To conclude: What I have tried to do here is to draw a roadmap towards an argument that I will eventually make in full, to suggest and to start to test out some methodologies that will eventually encompass many more post-colonial and post-modern rereadings of the various legends and histories of the figure of the Cid. Where the discourse has been informed, for better and for worse, explicitly, implicitly, and, as Borges might have had it, acaso sin quererlo, by a 19th and 20th century program of nationalizing the past, the literature of modernity — the cultural artifacts of a world itself shaped by a greater multiplicity of ways of knowing — of can serve to reframe the nationalist questions of history, historiography, and text, and to highlight and reassert the locality of knowledge — both the temporally local in the Middle Ages and the geographically local found in the global spread and reception of the PMC in the modern period — in productive reassessments of the development of national identity in the “Reconquista.” The Moor’s Last Sigh, like its fellow postcolonial and post-Imperial rereadings of the life of the Cid, plays deceptively with text and with familiarity, offering both up to the reader and the medievalist, ultimately challenging her to reconsider the texts she thinks she knows.