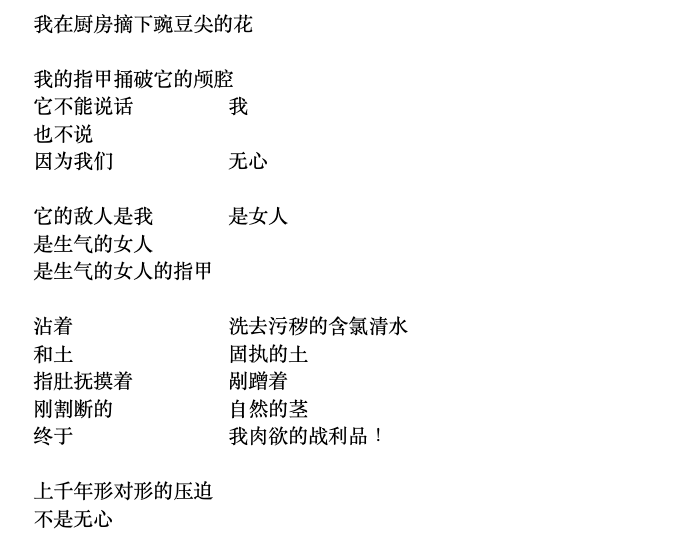

我在厨房摘下豌豆尖的花

探望 — a translation of Tian Tian’s “Visits”

我从淋浴和工作牢骚中

偷出几秒

把它们聚集起来

就这么囤着,

轻轻的,还沾着肥皂印

它们挣扎,挣扎着要离开

——从趾间偷偷溜走——

而我们假装对闹钟不予理睬。

天空穿透扭动的树枝,

蓝得并不寻常

窗外清醒的凿岩机振振有词,

城市从数月的昏迷中开始活跃

我们,也一样

几周前有鸟

黎明轻唱我们从未有过的歌

我不会等尴尬的暗示,

让我们假装 离开是我的决定,没关系

回家路上

我踉跄地度过这仅存的几秒

有些 掉在了路上

我仓促地拽它们回来

但秒钟却被吹入新早高峰的车轮下

司机并不留意:衣着整齐,害怕/无聊

琢磨起了午餐与未来/痛苦

人们的躯体中 嘴巴最不善表达

透过层层叠叠的蓝与白

我学会读懂眼睛

我看着时间这一活物行走

干线边的郁金香得意地站立

毫无香味

滋味 (translated excerpts of “Flavor” by Alexandra Mathew)

Read Alexandra Mathew’s ‘Flavor’

Read Xiao Liang’s ‘Reflections on translating Alexandra Mathew’s ‘Flavor’ into Chinese’

凭什么你的心魔驱散后,我的存在

也被摧毁。

真实的交换只能发生在,我们的香料与你们的

自我憎恶中。

过多辣椒并不让香料滋味太浓,而是

“为什么你要加这么多葛拉姆玛萨拉?”

……

我们的民族当然是做了什么好事,不然为什么你总是

早起

祈阳

用无麸质饮食与牛肉一同调理你的脉轮

的士高是什么 (translated excerpts of Hoiyan Guo’s “What Is Disco”)

Read Hoiyan Guo’s ‘What Is Disco’

的士高 ——

要是你不喜欢缩写的话,那就的士夠格

像罐能量饮料

喝起来怪怪的,但有些人就是

情有独钟

的士高——

要是你非得来法国人那一套,那就discothèque

是舞池里七分钟的动感节拍混合另一个七分钟的动感节拍

不然就是

从舞池里七分钟的动感节拍修剪成短短三分钟

在你车里,缓慢淡出

Reflections on translating Alexandra Mathew’s “Flavor” into Chinese

Read Alexandra Mathew’s ‘Flavor’

Read 滋味, Xiao Liang’s translated excerpts of ‘Flavor’

Flavor is Alex’s reflection on people’s appropriation of Indian culture. She touches on many troubling practices such as generalizing spices, upturned noses, following certain trends without respecting or understanding Indian culture… I had a tentative translation but was not satisfied with it. But the process of translating it has been a really intentional effort at not “appropriating” the culture again in Chinese. It requires me to deal with this poem with care and respect.

For example, how to translate those really specific Indian cultural products/practices? “Garam Masala” is itself a rendering in English by pronunciation, then with Chinese, does the same approach still apply? There are two options actually: one is phonetic translation “葛拉姆玛萨拉,” while the other is “综合香辛料”(mixed spices). The latter isn’t really specific about Garam Masala, and is just as general. With “葛拉姆玛萨拉” there is an intentional difference being highlighted, because these characters clearly constitute a “foreign” name, so that it separates itself from the other generalizing, appropriating practices.

Same with “chakra,” there is also a phonetic translation “查克拉.” With regard to renderings more towards its meaning, the common translations are 脉轮(脉:vein, connection, network; 轮:wheel, cycle) and 气卦(气:qi, energy; 卦:symbols, but also appears in the famous Chinese “八卦”). Here I chose 脉轮 because it retains the “wheel” meaning in chakra and roughly capture the meaning (although there is definitely more research required). I didn’t choose 气卦 because the two Chinese characters automatically remind me of the concepts of 气 and 八卦 in Chinese metaphysics, which might risk appropriating it even again by associating it too closely with Chinese culture. What’s interesting is that there are three layers of culture contained in one translated poem. There’s the Indian culture the poet hopes to protect, the American “modern,” “trendy” culture being criticized, and then a translation produced in the Chinese language. Why should a Chinese translation of it exist? What responsibility is a Chinese translation of it burdened with? It really provokes some interesting questions for me to think about.