Auditory ‘Temple Run’ – Jackson Simon – Rodolfo Cossovich

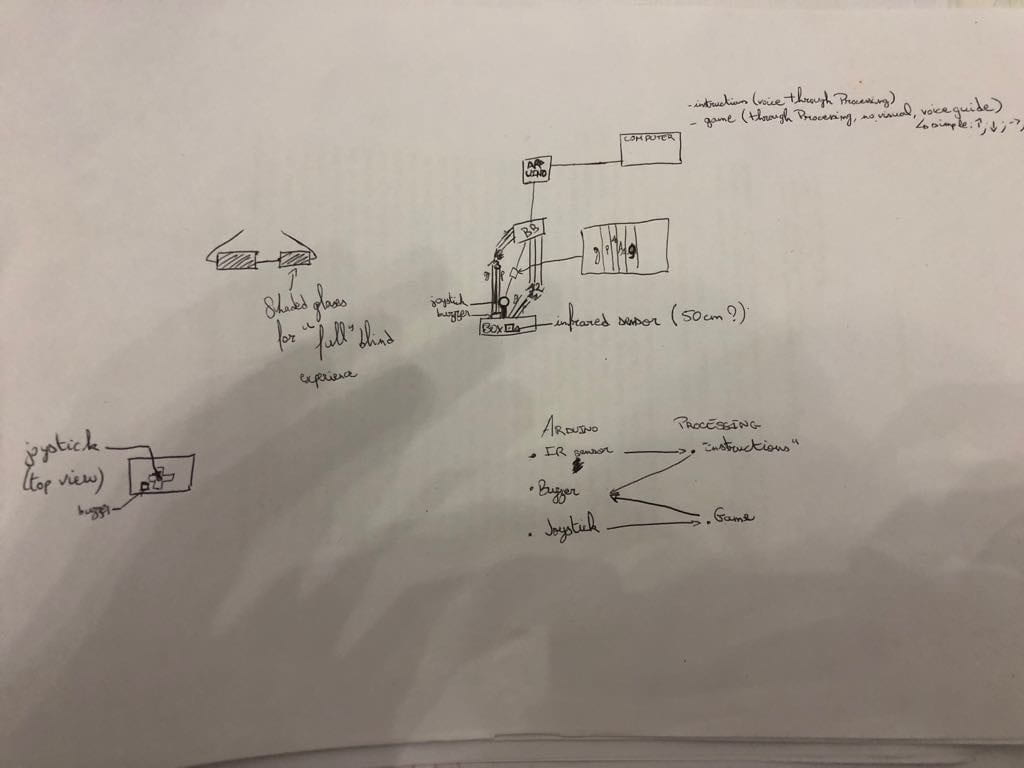

Conception and Design:

I started off just really wanting to create a game, and through conversations with Rudi “Temple Run” came up. I was not about to create a replica of an already made game, but I had this idea that “Temple Run” could be turned into a pure audio game. Audio of a direction played would let the user know where to go, instead of having visual aid. At first, this audio game was intended to try and potentially help visually impaired people in some way (perhaps helping them know which way they could move in a day to day life, while walking down the street, with the directions being said out loud). However, this was quite presumptuous seeing as I do not know people who have lost, or never had, their eyesight. Therefore, I could not accurately figure out what best way to aid them. The game then turned into an inclusive game, allowing both people who can see, and those who cannot, to be on the same playing field and enjoy themselves.

Fabrication and Production:

In the beginning (for user testing), I neglected to emphasize the experience of being blind for those who indeed were not. In fact, I started with a joystick as the means of going up, down, left or right. After the feedback I received, it was clear that I needed to switch the way of interacting with the game, and after conversations with Rudi: I decided to use an accelerometer attached to a headset with ‘blinding’ glasses. This allowed for an amplification of the dulling of senses. I realize now that a gyroscope might have been easier, and more successful, in reading the directions (now attached to the way the user moved their head) and in user usability. I believe changing the way the user moves directions, while having their eyesight dulled (for users who are not visually impaired), made it so that a sort of equal ground for playing games was added. Plus, it made it more fun and interactive in a different way then just a simple joystick.

Conclusion:

This game was meant to be able to be played by visually impaired and non-visually impaired people alike. My definition of interaction doesn’t necessarily involve a back and forth: it could be, for example, just reading a book, the words interacting with your brain, however, your brain doesn’t necessarily interact with the book. In the case of my game, there is a back and forth: the sound with the user, the user with the accelerometer (and by extension the game itself). Therefore, my game adheres to my definition but also expands it since there is more than just a singular interaction (which I believe is all that is needed for something to be called an interactive exchange). The audience therefore receives a stimulation, and causes a stimulation themselves.

If I had more time there is some definite improvement that I could’ve done. For example, improve the ‘blinding’ of non-visually impaired people (even after tweaking the glasses multiple times you could still sort of see through the corner of your eye) and also make sure that the directional readings were as perfect as could be (they worked well, you could definitely get ten points by going in the right direction 10 times, but it still was a little off at times). It has taught me that the experience had by the user for a game is paramount. I got complaints about the uncomfortableness of the headset (which definitely could’ve been made to be nicer), which leads to people not necessarily wanting to where it: which means they wouldn’t play the game! If I were to make another game, similar or not to this project, I would put more focus on the experience (even though I had people that did enjoy it and have fun at the IMA Show) and not just the idea behind the game (even if it is still important).

So what? Why should people care about this project? It definitely did accomplish my goal to a certain extent: a level playing field, no matter if you can see or not. I feel that equalizing the way games are played, while enhancing user experience, is a goal all games should strive for.