Title

The Station of the Metro

Project description

The Station of the Metro is an attempt to demonstrate the daily experience by real-time audiovisual. It based on the different video clips shot in the real station in Shanghai and integrated by the new digital way of demonstration. Traditional photography shows new meanings and aesthetic value in this way.

Our inspiration comes from the poem of Ezra Pound, In the Station of the Metro and the name of our project is borrowed from his poem. The origin poem is as follows. The apparition of these faces in the crowd. Petals on a wet, black bough. As a quintessential Imagist text, the treatment of the subject’s appearance by way of the poem’s visuality. Thus, it is quite suitable to reveal the artistic conception of this poem by audio-visual performance. Basically, we want to emphasis the loneliness of a person in the noisy crowds and demonstrate the low temperature behind boisterous society. The overall atmosphere of our project is dark, cold, and depressive.

Perspective and Context

Our project The Station of the Metro belongs to the category of live cinema. According to Chris Allen, a member of The Light Surgeons, live cinema is a “deconstructed, exploded kind of filmmaking that involves narrative and storytelling” (91). Different from VJing, which highly emphasis the interaction between presenters and audiences, live cinema demonstrates a more personal view and artistic concept during the performance. The Raindrops #7 and Strata #2 we saw in the class were my favorites. I was surprised and excited to see how normal scenes in our daily life can achieve such a great aesthetic value. The traditional videos combined with digital and technical form demonstrate strong vitality

Quayola, “Strata #2,” 2009

What’s more, we were also inspired by Glitch Art. The sudden distortion occurs in video or sudden white noise in audio not only achieves harmony but also demonstrates some features of Glitch Art. Glitch Art comes from digital art and also serve digital art currently.

Development & Technical Implementation

The development of our project can be developed into two parts, materials collection stage, and technical stage.

We started the first stage early as we did not know what kinds of video we needed in our project. On the one hand, we wanted to present the atmosphere demonstrated in In The Station of the Metro written by Ezra Pound. On the other hand, we hope we can integrate our daily experience in the real station. Luckily, when we first shot in Century Avenue station, we found a girl squatted in the corner while the crowded rushed to pass by her without a glance. The quiet girl stands in sharp relief against noisy crowded and delivered a strong sense of longlines. We were deeply impressed by this scene and found it not the only one. Thus, we decided to emphasis this kind of contrast between loneliness and noise through our project.

We found a lonely girl and a still boy in the station

I did most of the job in the collection stage including video collections and audio collections. According to my previous experience in photography, I used time-lapse photography and made thousands of photos into a video. In this time-lapse video, the crowds are like water flowed around the still person. I selected different locations to shot videos, including the subway entrance, subway platform, and ticket entrance. Also, I particularly chose morning peak and evening peak to shot the video to achieve the best effects. Additionally, I shot rainy car windows which reflected stunningly beautiful lights. We planned to fuse it with station video to create an obscure, romantic and idiosyncratic atmosphere.

I took time-laspe photos in the entrance of station

I made a time-lapse video

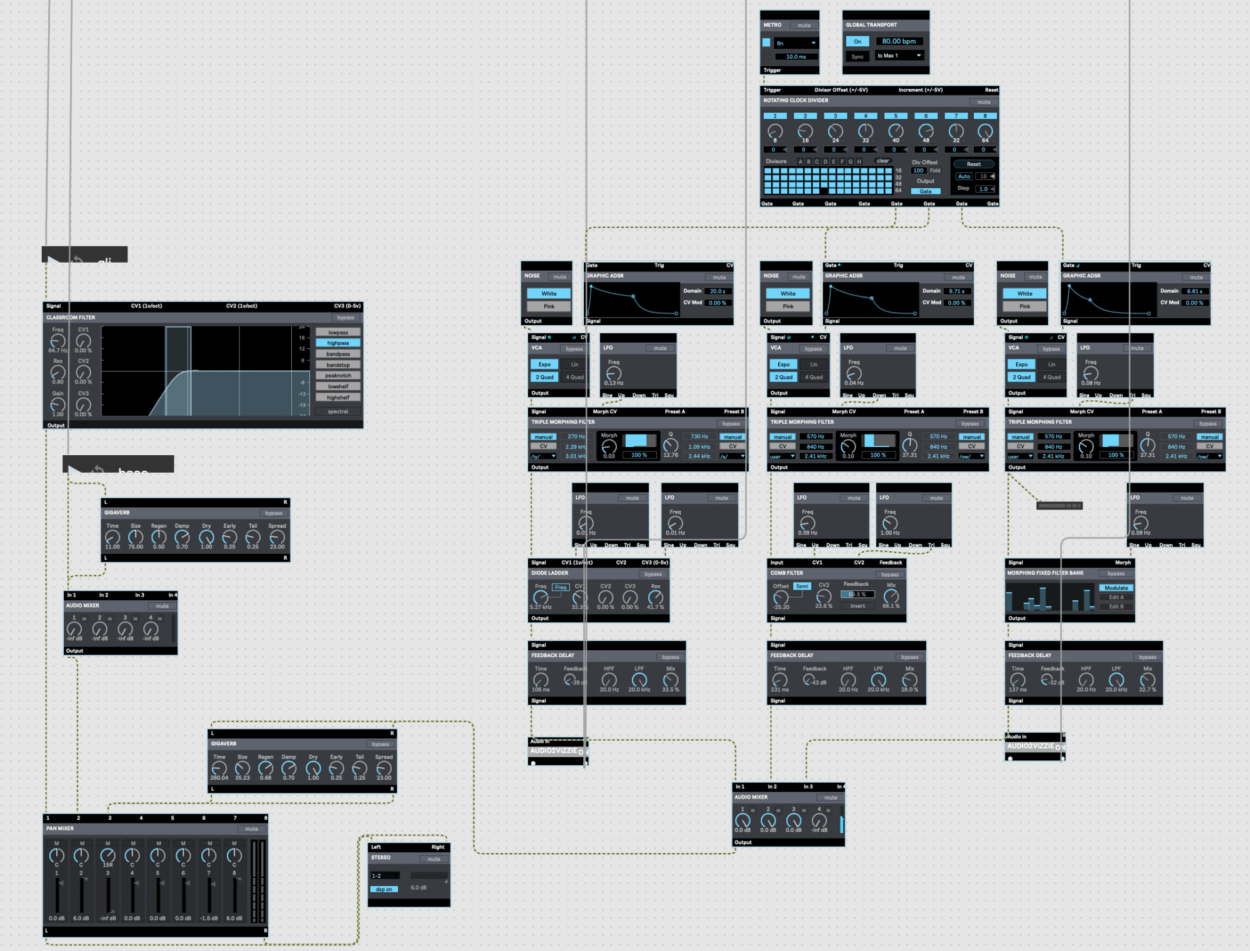

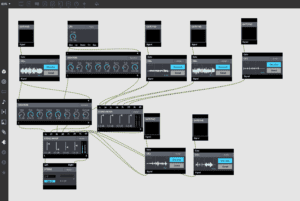

In the early technical stage, Katie editing, splicing, cutting and simply post-processing raw video materials with Pr and I made a piece of background music by GarageBand. I firstly used the piano to write a theme and then changed its volume, pitch, timbre, and rhythm. Based on the looped theme, I added different notes, including the bass with a long extension and volume change as well as silvery high pitch. Overall, the basic background music does not have a strong beat and shows great rhythm and delivers a sense of dark and repression.

i made a background music for our project

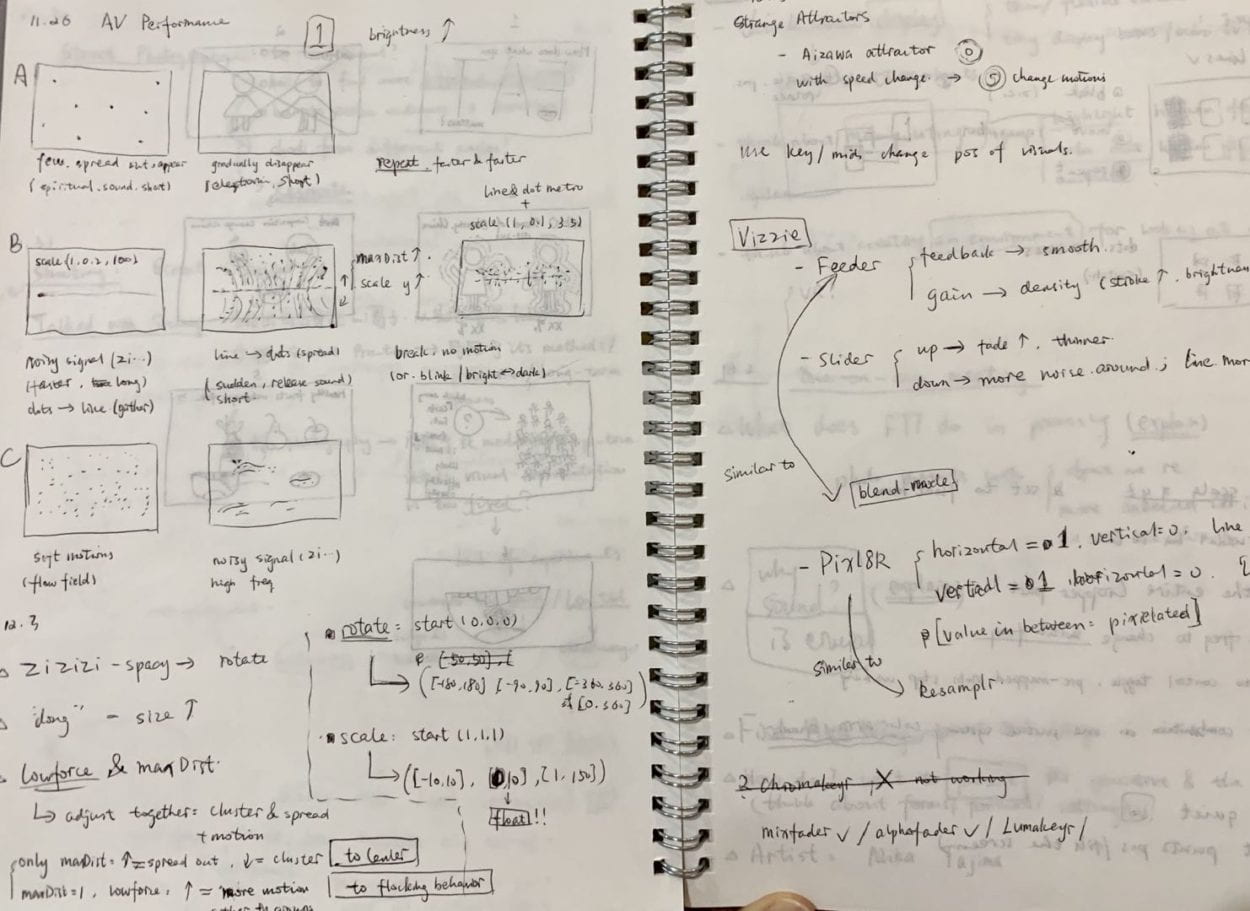

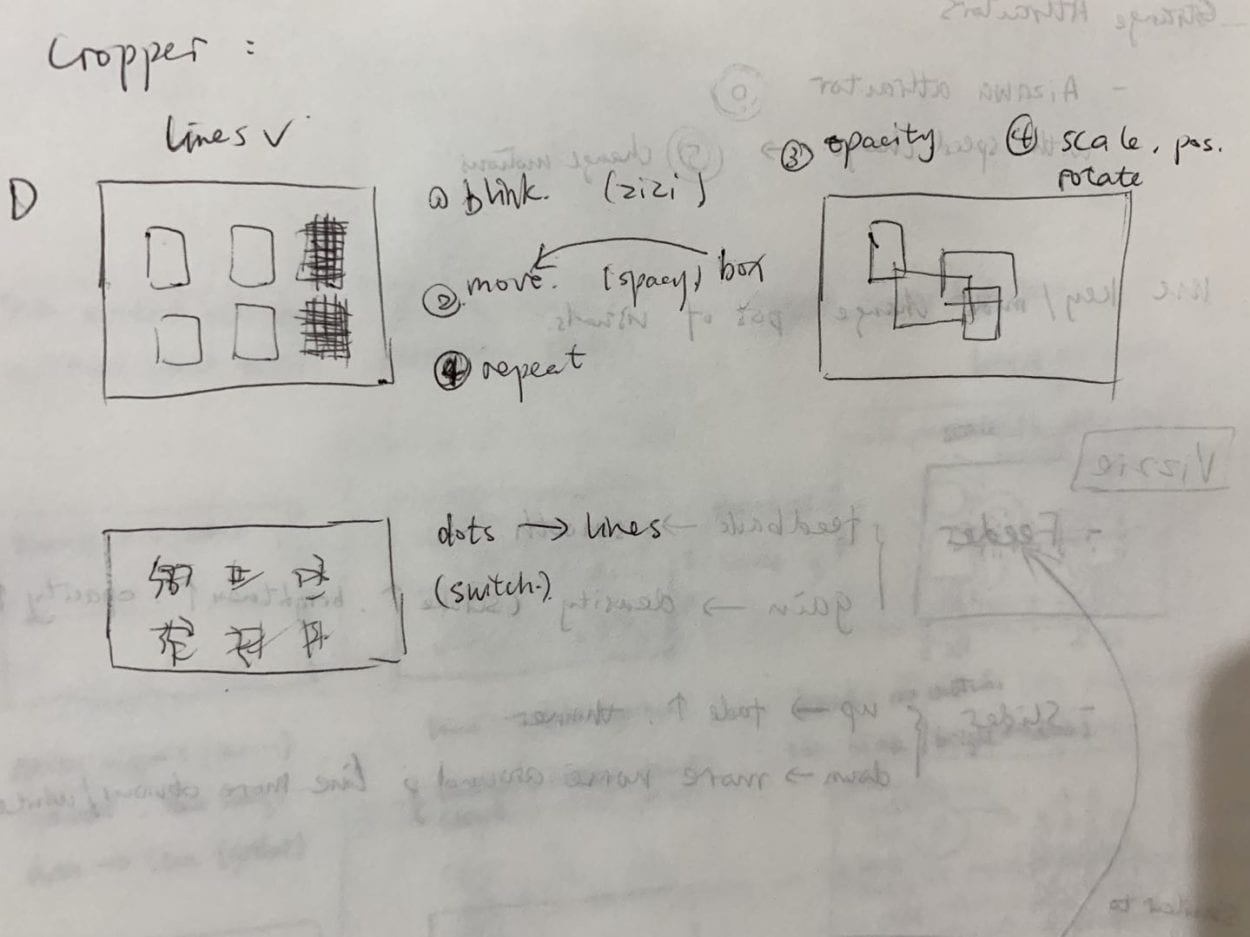

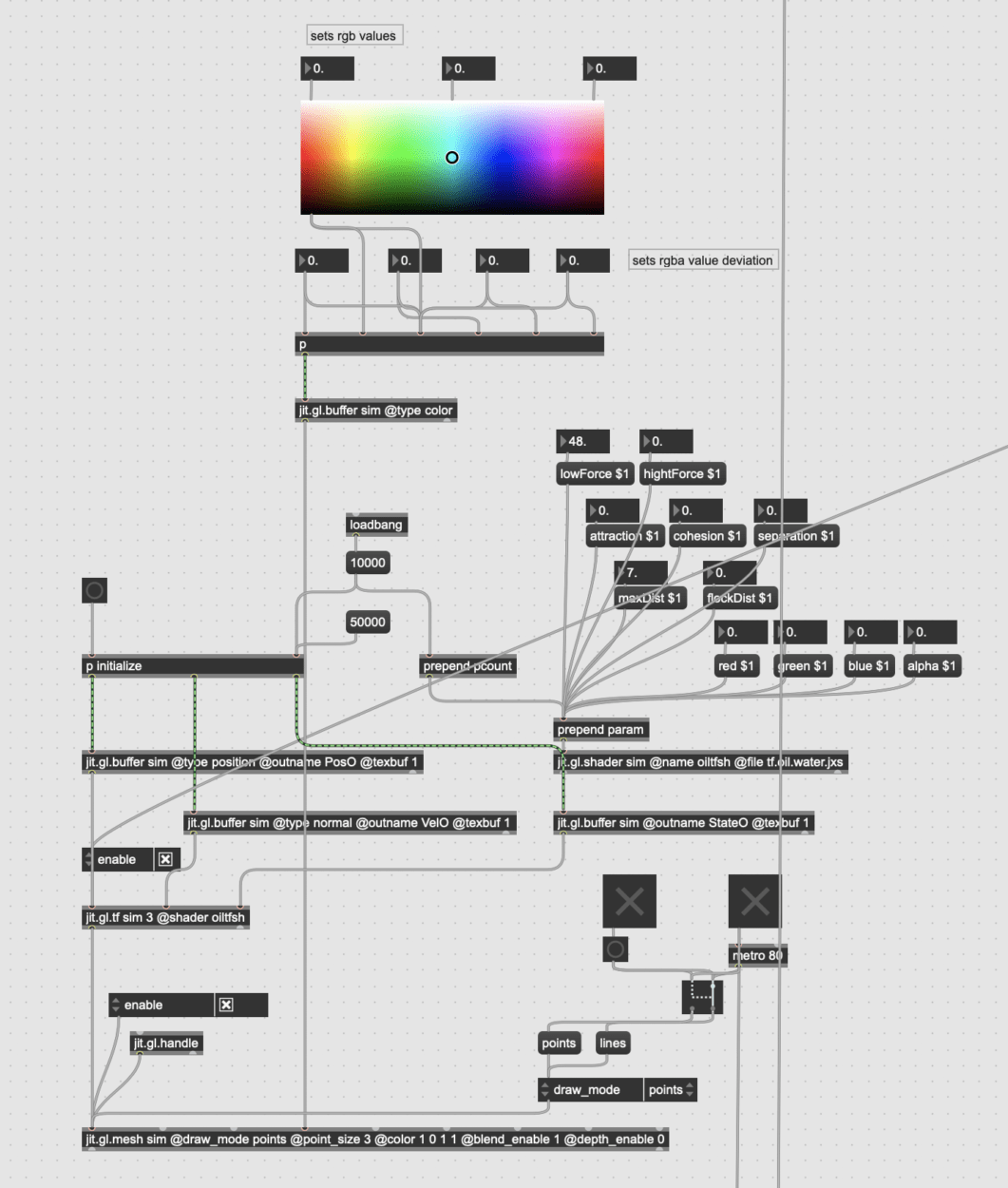

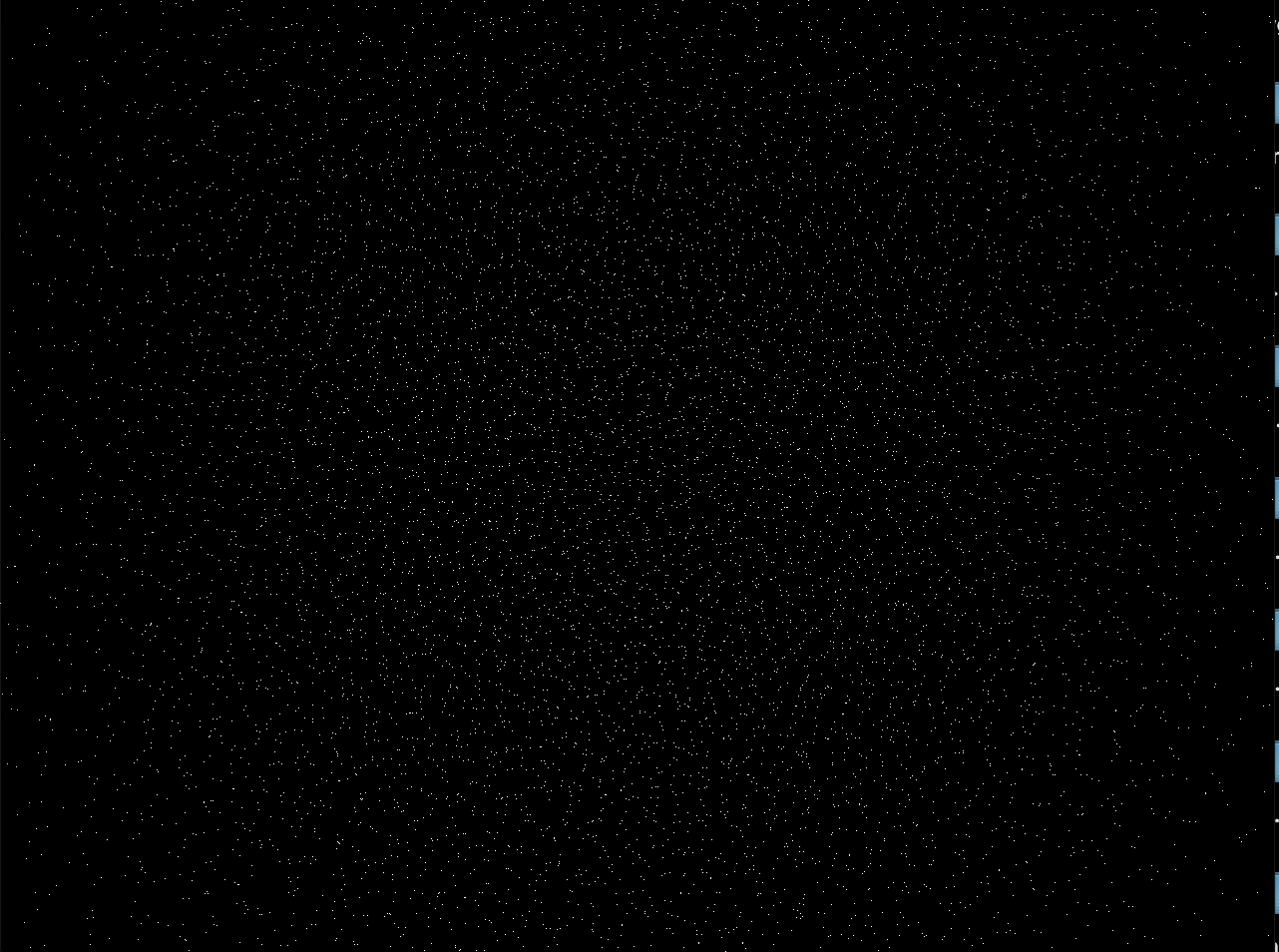

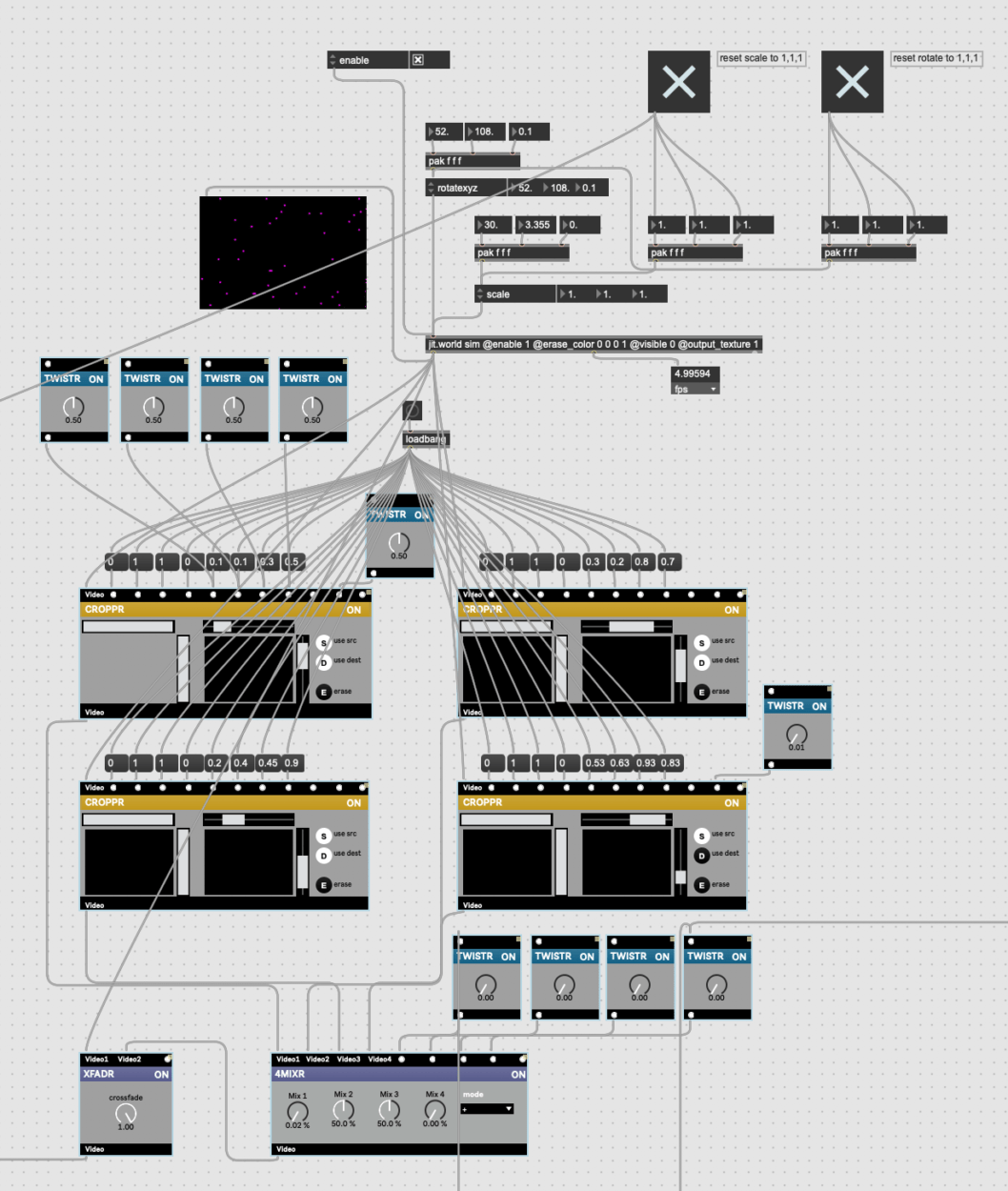

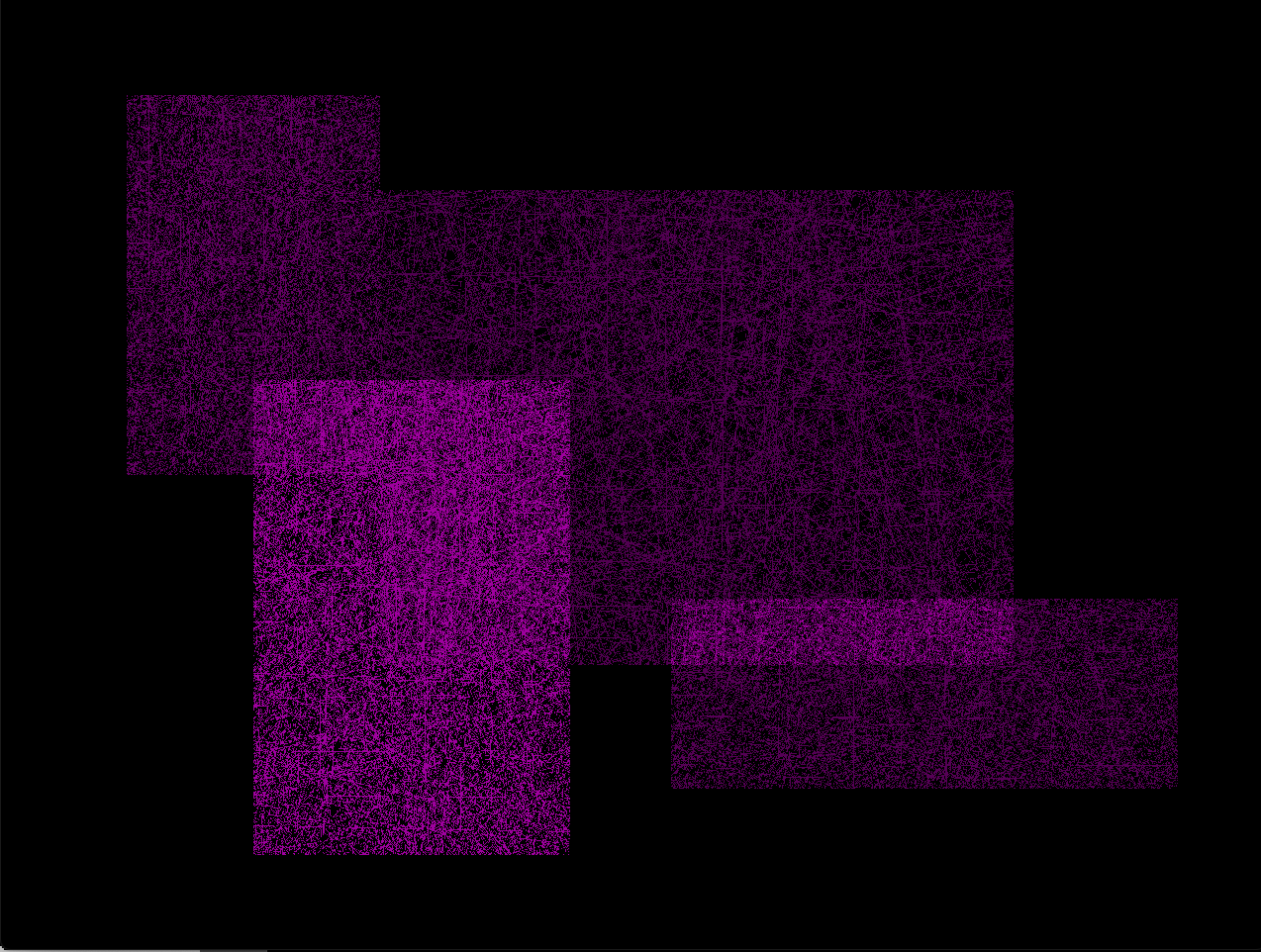

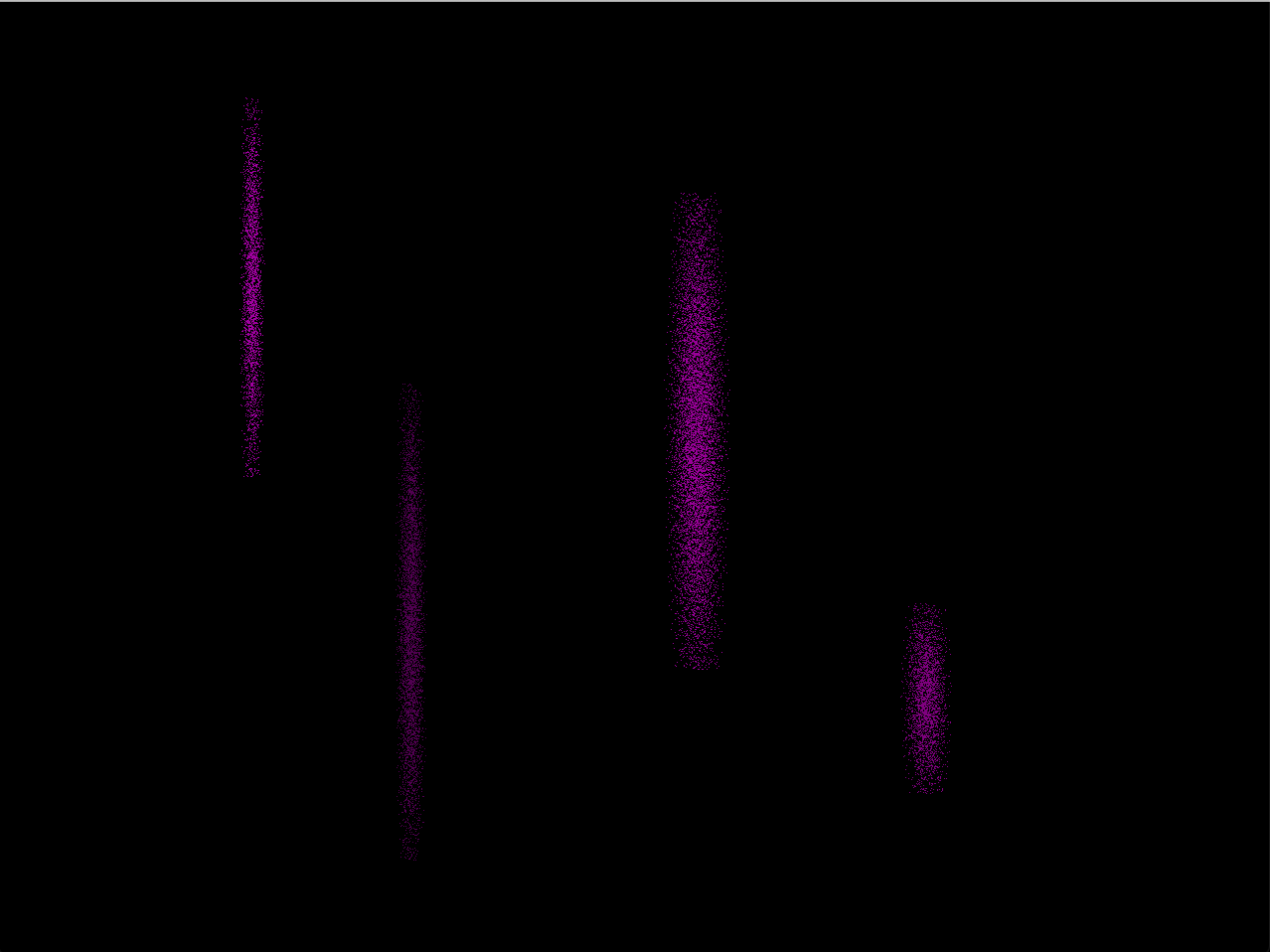

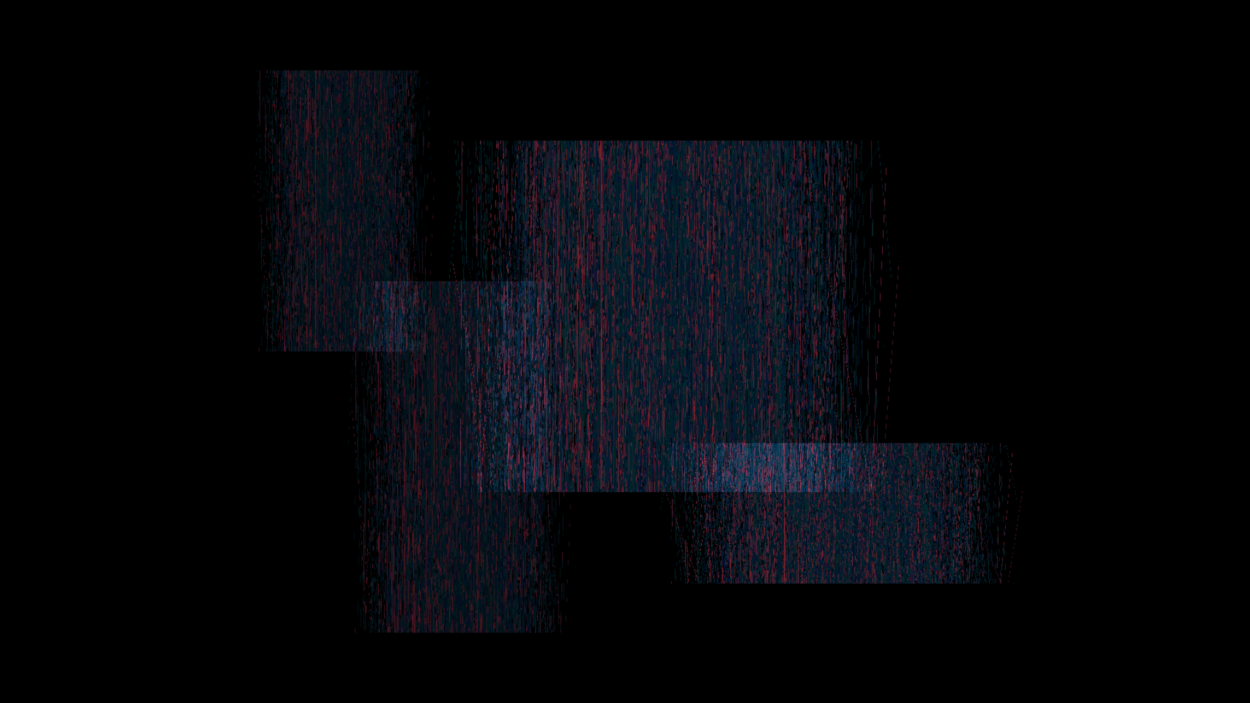

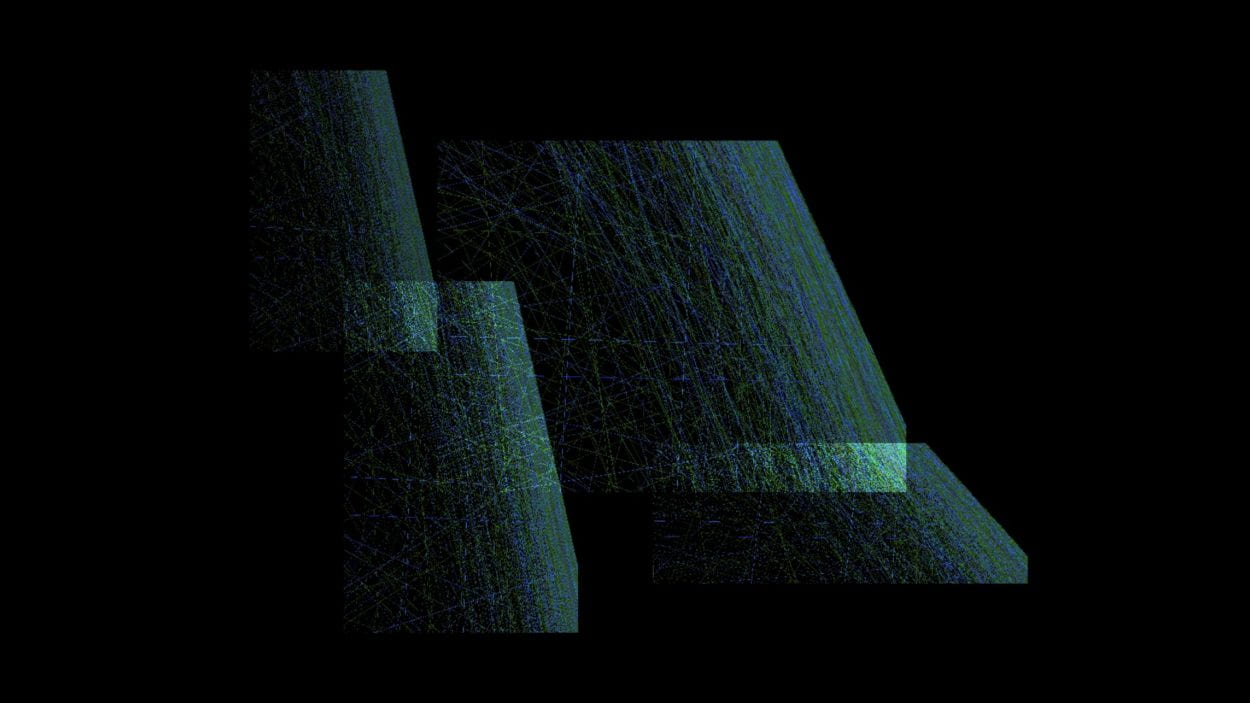

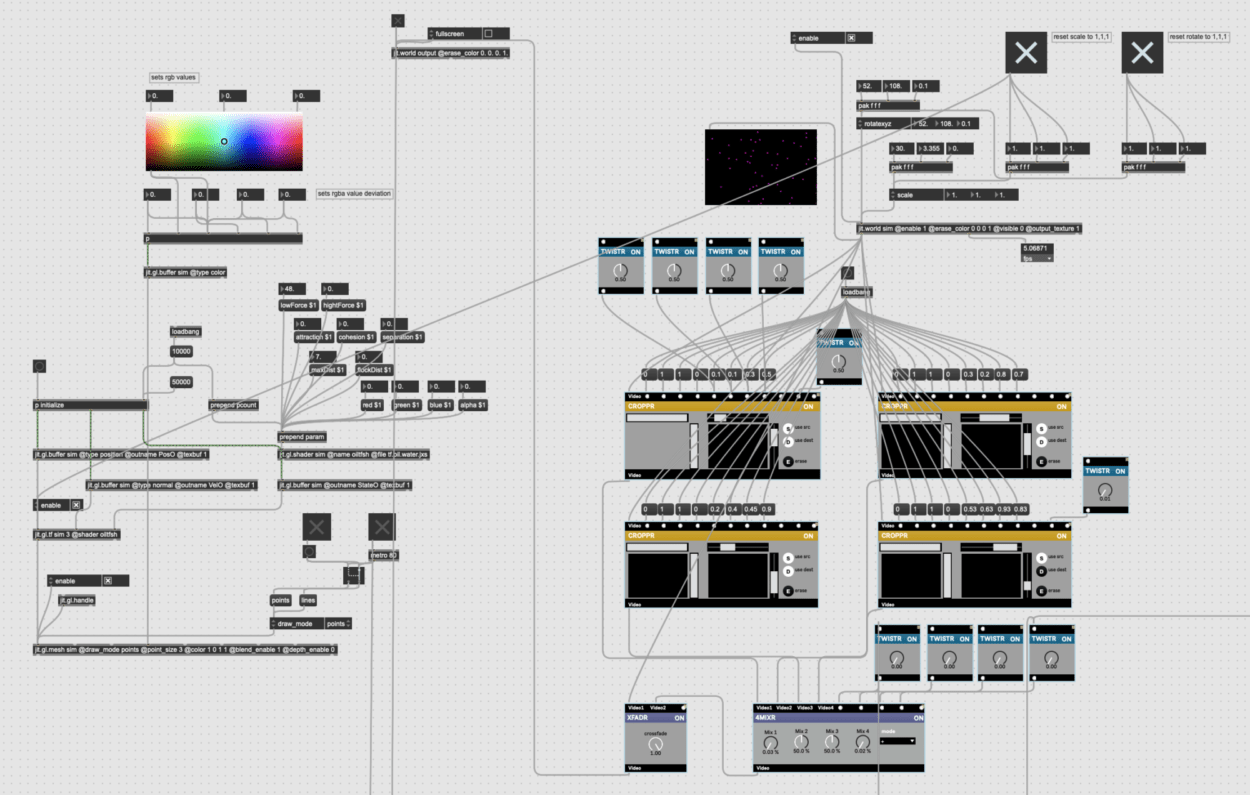

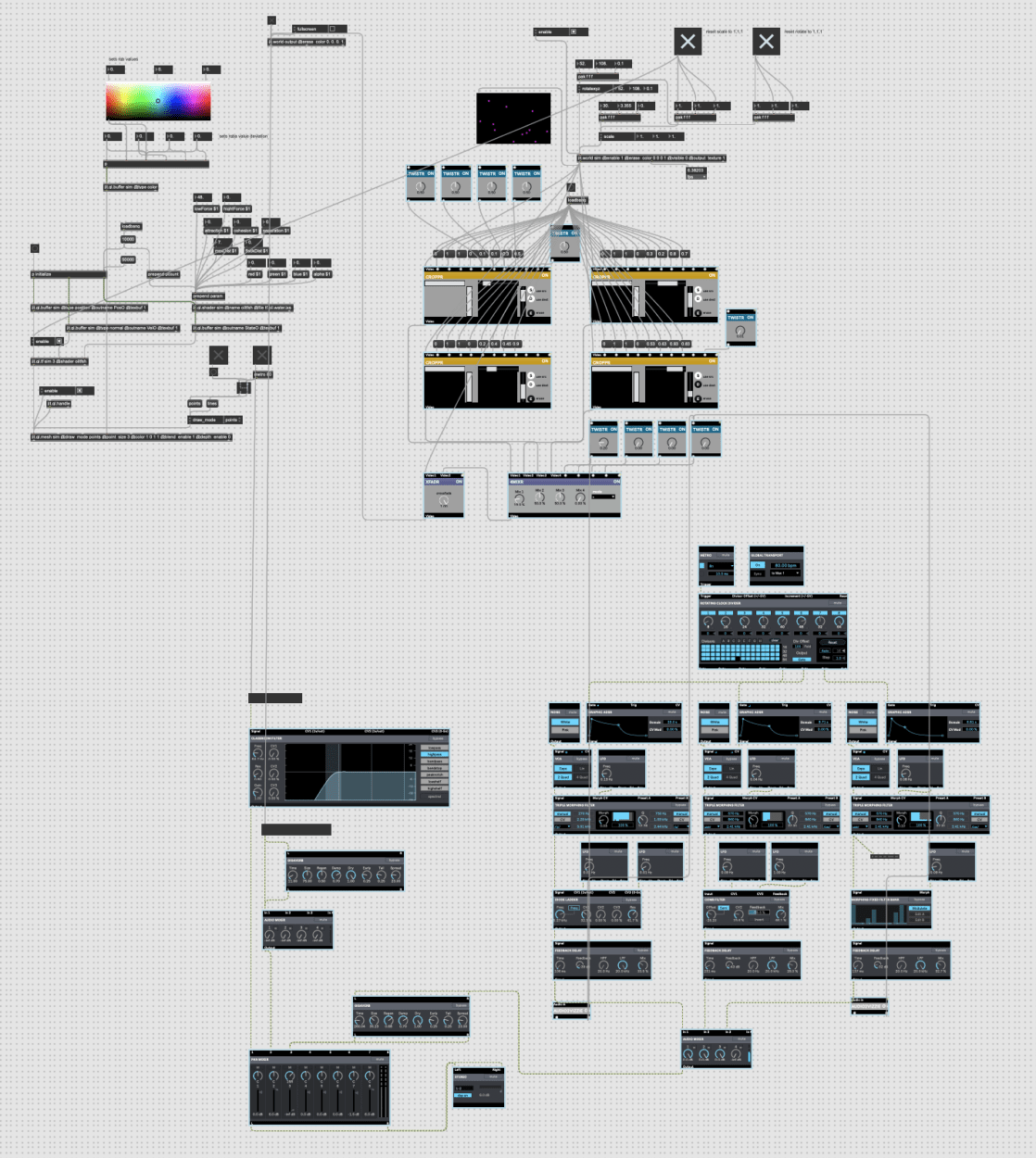

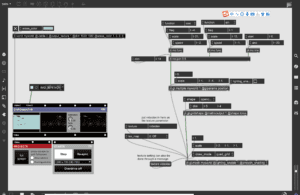

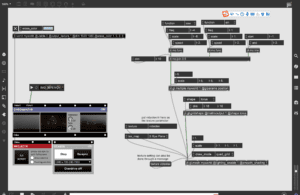

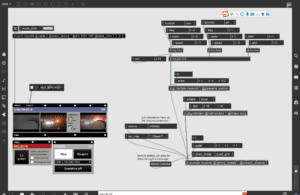

In the post technical stage, we put our background video and music into MAX. For video, Katie and I almost explore every possible effect and we found something quite suitable for our videos. Besides, we spent a lot of time creating and adjusting the 3D model in our project as well as finding suitable effects. We created three wonderful 3D models that perfectly fitted our project. However, as it was hard for us to precisely one change 3D model to another, we regretfully chose one and gave up two. What’ more, to develop a harmony consistent between the 3D model and background video, we adapt the size, light, and texture of the 3D model. We were satisfied with the final results. For audio effect, I want it to show a tight and dynamic relationship with videos. On the one hand, I changed the SIZE of audio and added white noise when the videos constantly shift or when certain video effects occur. On the other hand, I add the sound like jewelry collision when the 3D model occurs. We want to give our audience a sense of synesthesia These through the harmony between audios and videos.

3D model 1

3D model 2

3D model 3

audio patch

After these two stages, we worked on how to run everything in perfect order. I wrote a basic script including three timelines. Firstly, I analyzed the important time point in the background video such as video shift or video superstation. Then, according to this timeline, we jointly decided the time points of different effects including DELAY, ROTATE, COLOR as well as the time when the 3D model occurs. Finally, I planned the audio effects based on the former two lines. Followed the basic script, Katie and I rehearsed many times and constantly add new things and adjusted the old things.

Performance

Video clips:

The overall performance went well and was better than any of our rehearsals. I appreciate that we could perform in an underground club, where the room is completely dark and the sound equipment is advanced. Besides, because our project was the first to present and the overall atmosphere was relatively quiet, the performance effect was better than our expectations. We want to demonstrate the dark, heavy and depressed in the fast-paced and crowded station through our project, which is perfectly consistent with the dark and quite underground club. In our presentation, I mainly controlled the audio effects while Katie controlled the video effects. I think I did much better than before. I cautious followed the video and the video effects to adjust the audio effects. The overall audio effects and video effects are in harmony and follow our script because of our previous multiple rehearsals. Katie and I showed great tacit understanding during the performance. Although some effects did not perfectly follow the rhythm, our quick adaption balanced the tiny mistakes. More excitedly, just before 30 minutes we left for the club, we found a new video effect that was quite suitable for our project and this effect went very well during the presentation.

However, there was still something unexpected. Although we have rehearsed a lot of times, we still did not achieve all the effects we planned. Firstly, the audios patch crashed three times before performance, I rushed to develop the patch so some detailed settings deviated from the original one. Secondly, the output device on my computer did not work steadily and I was always worried about it during the presentation. Thirdly, as we were the first presenters, both Katie and I were a little bit nervous and made some mistakes.

I enjoyed being a presenter of this real-time audiovisual performance. Although we were not so confident about all the effects and we experienced a lot of tension, we gained happiness and satisfaction when we successfully finished our personation and gained positive feedback among the audiences. It was quite an exciting experience.

Conclusion:

It is a valuable experience for me to develop an audio-visual project and present it in public. I was also proud that when I finished the performance, some people came to give us great praise. Although it took me a lot of time, the satisfaction and happiness I gained from the project exceeded struggling. Different from other projects that mainly made by MAX itself, we shot video from the most common senses in our daily life as a background video and post-processed with MAX as well as combined 3D models. Personally, I appreciate such an idea that art comes from life and life can become an art. Through our project and presentation, the normal station showed aesthetic value and demonstrated unusual aspects. That is exactly the most meaningful thing to me.

Besides, we had successful cooperation. We not only shared the work equally but also play our strengths. More importantly, both of us had great passion and curiosity for MAX. We explore different possible effects until the last time. We gained infinite excitement when achieving new things.

Of course, as things can never be perfect, we still have many areas to improve. On the one hand, we could be more confident during the presentation. Honestly speaking, due to our nerves, we made a lot of tiny mistakes. On the other hand, the structure of our project can be much better. After watching the video of our presentation, I found that we did not emphasis the contrast between a still person and noisy crowds. Although we did some emphasis, for audiences, they may not receive this simply through our presentation. It is an important experience and I need to pay attention to deliver information coherently and clearly for my audiences to follow and understand.

References:

Menotti, Gabriel, “Live Cinema,” in The Audiovisual Breakthrough (Fluctuating Images, 2015), 85.

Raindrops #7

Quayola, “Strata #2,” 2009