The first four chapters of the book Understanding Comics—the Invisible Art made my 12-year confusions towards comics clearer since I read Japanese animation and comics. I am a big fan for renowned Japanese comics such as Bleach and Hitman Reborn. Thoughts often came when I glance over the newest episode, or scroll over the websites for others’ comments about these animations: why the pages of drawing make sense even if they are not when seen separately or disorderedly? Why other fans own different views toward the same comics? What exactly does comics’ writers do, that leave space for fans to create further stories about characters (tongren in Chinese), using various media (games, novels, paintings, Anime Convention…)?…

If my confusions are based on empirical experience, then Scott McCloud gave a theoretical, comprehensive approach of understanding what is comics, and he explained it simply: comics a sequence of images based on the space, which have a narrative-like quality and visual direction to them. It could take multiple forms, from non-entity to material matter, image to voice… No matter what, writers are devoted to create comics as simple as possible, entitling the soul which could be further interpreted by the readers themselves, ultimately creating a new world where readers themselves become part of the story. The space between each scene and each page is used as an instrument, in order to create tension.

Hence, by Scott’s articulation, Japanese comics that I read on the book is only a part of what comics can be presented. Actually, four types composite the world of comics: sequential, visual, static, and iconic. The unique character that comics bears is its better job of delivering messages with emotions, such as anger, disgust and irony, using abstract and exaggerated forms. The jump between pages and drawings (when one reads Japanese comics for example), and a basic portrait of a scene (several dots and lines) would be sufficient for the readers to form the whole pic of the story by themselves. The consistency of the comics relies heavily upon people’s imagination, which is exactly the comics’ charm.

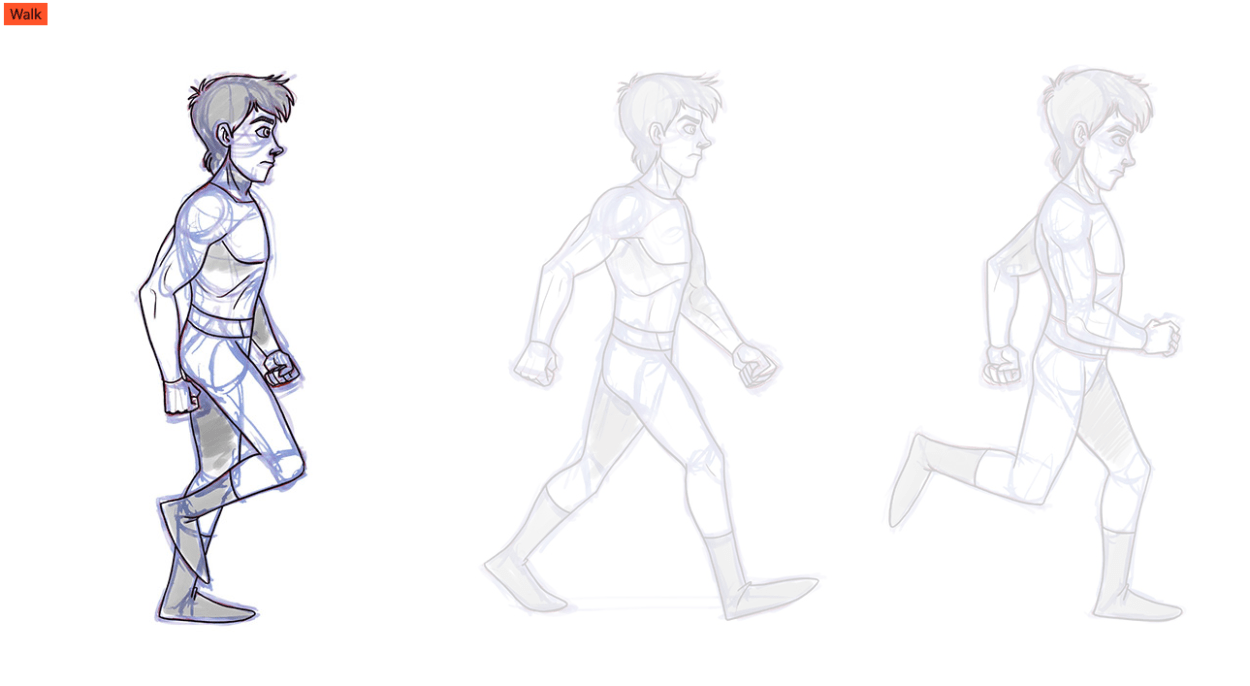

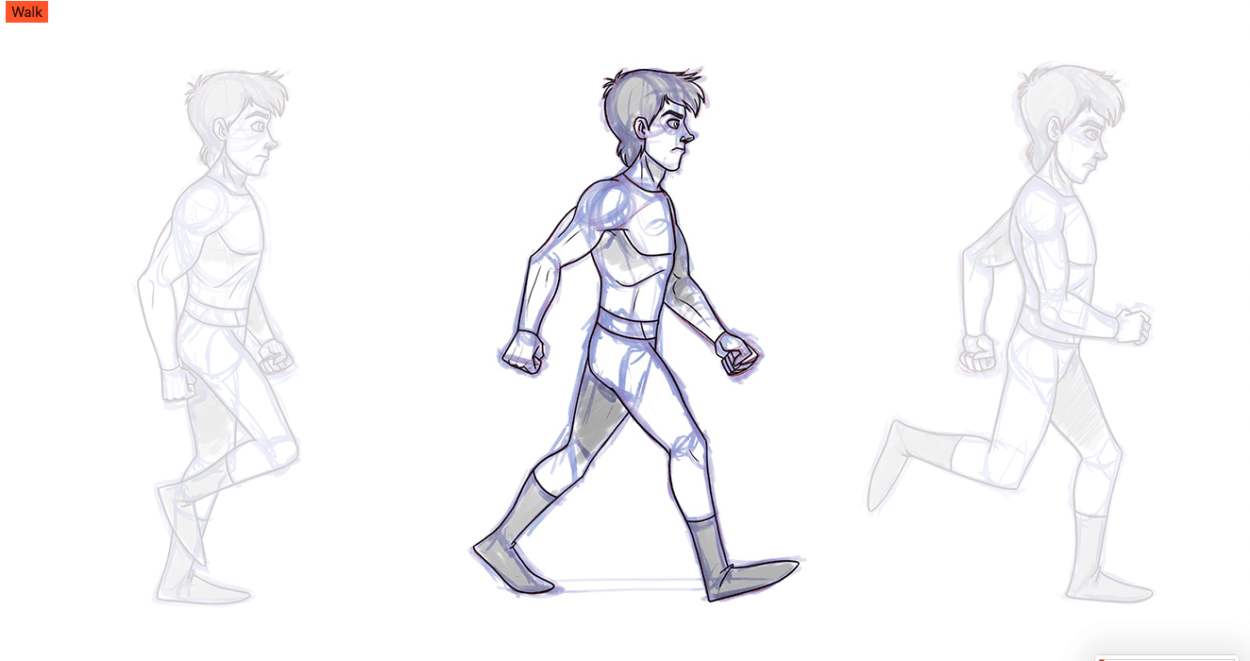

Another thing that impresses me is in Chap 4, where the writer identify the “time” in comics. Time is of significance as it can remarkably shift the outcome of story. For example, a rearrangement of a character’s sequence of doing things will drive the story into another direction. This is especially true when something exigent is added in, such as murder, rob or catching a criminal. Different ways in drawing the motion will play a part in affecting the timing too. Such as the more dashes behind a character, the faster you may think he/she is running.

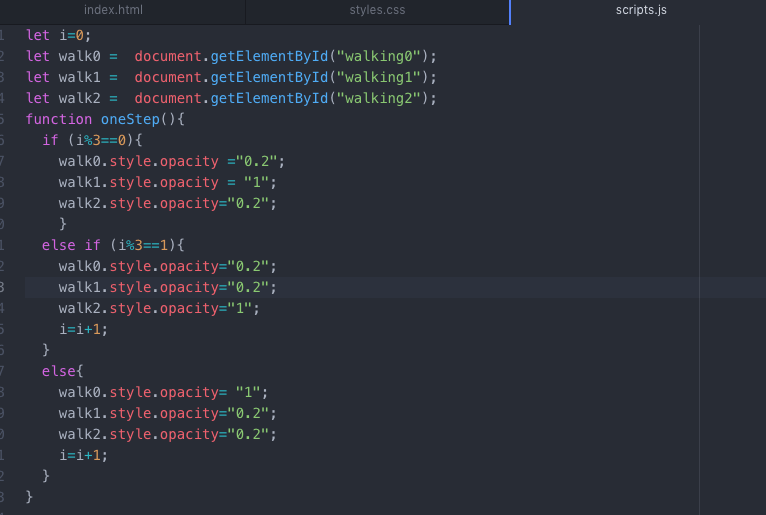

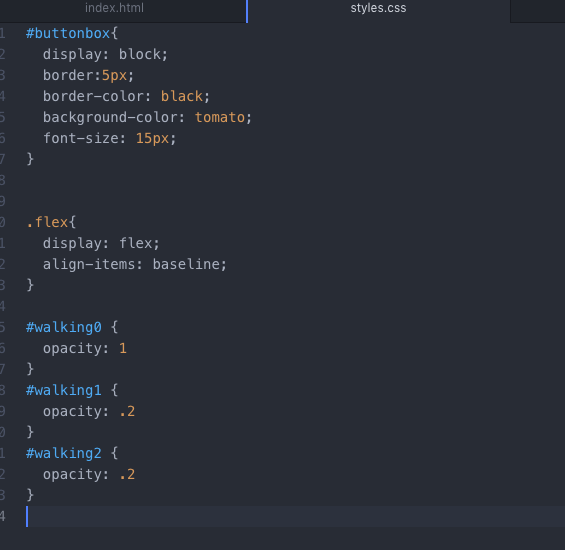

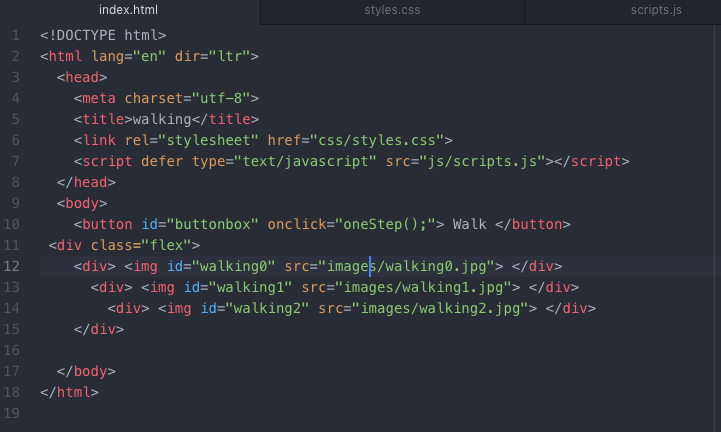

Here is the codes I have, I really hope I could make it through next week after discussing with the TA.

Here is the codes I have, I really hope I could make it through next week after discussing with the TA.