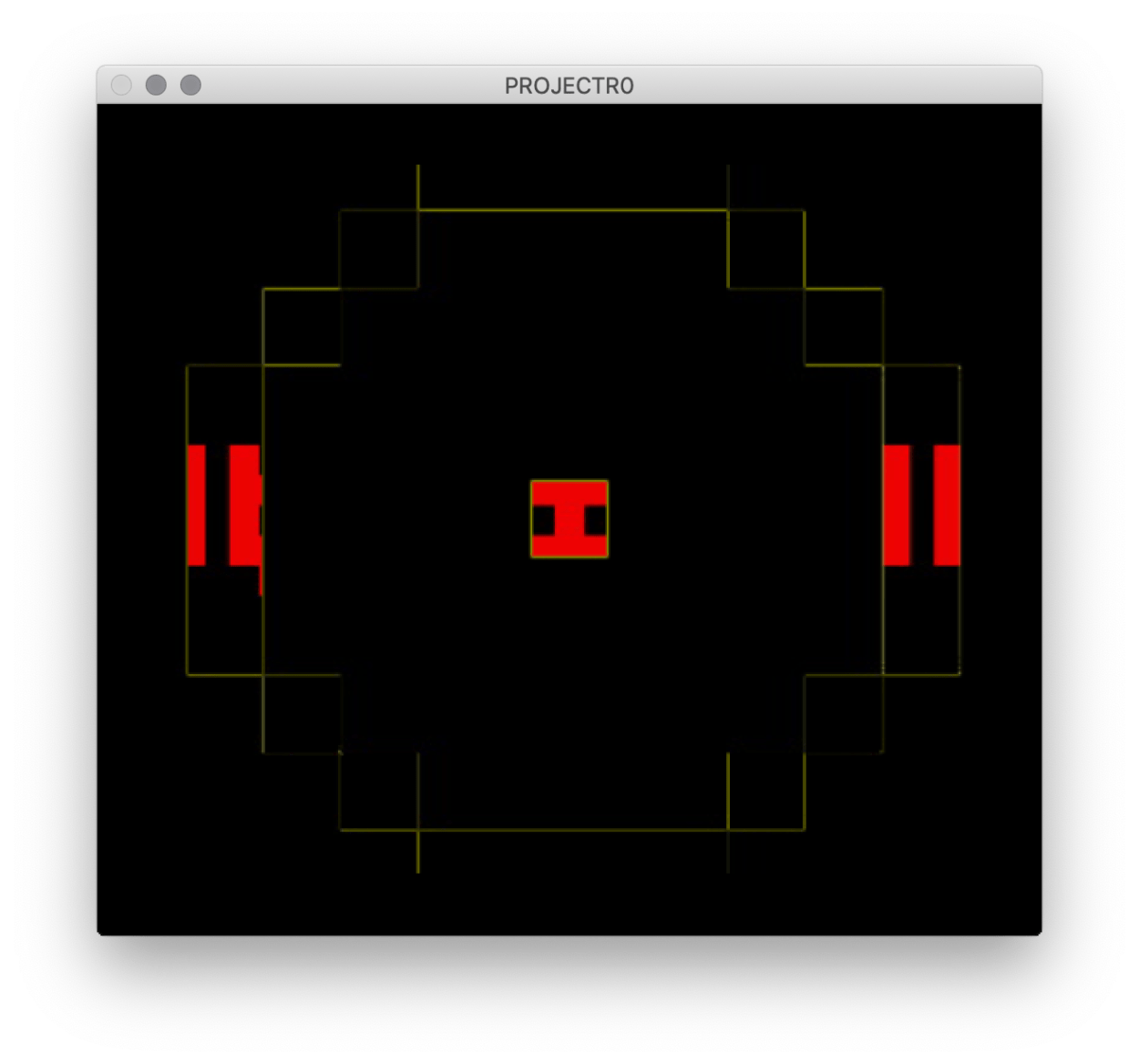

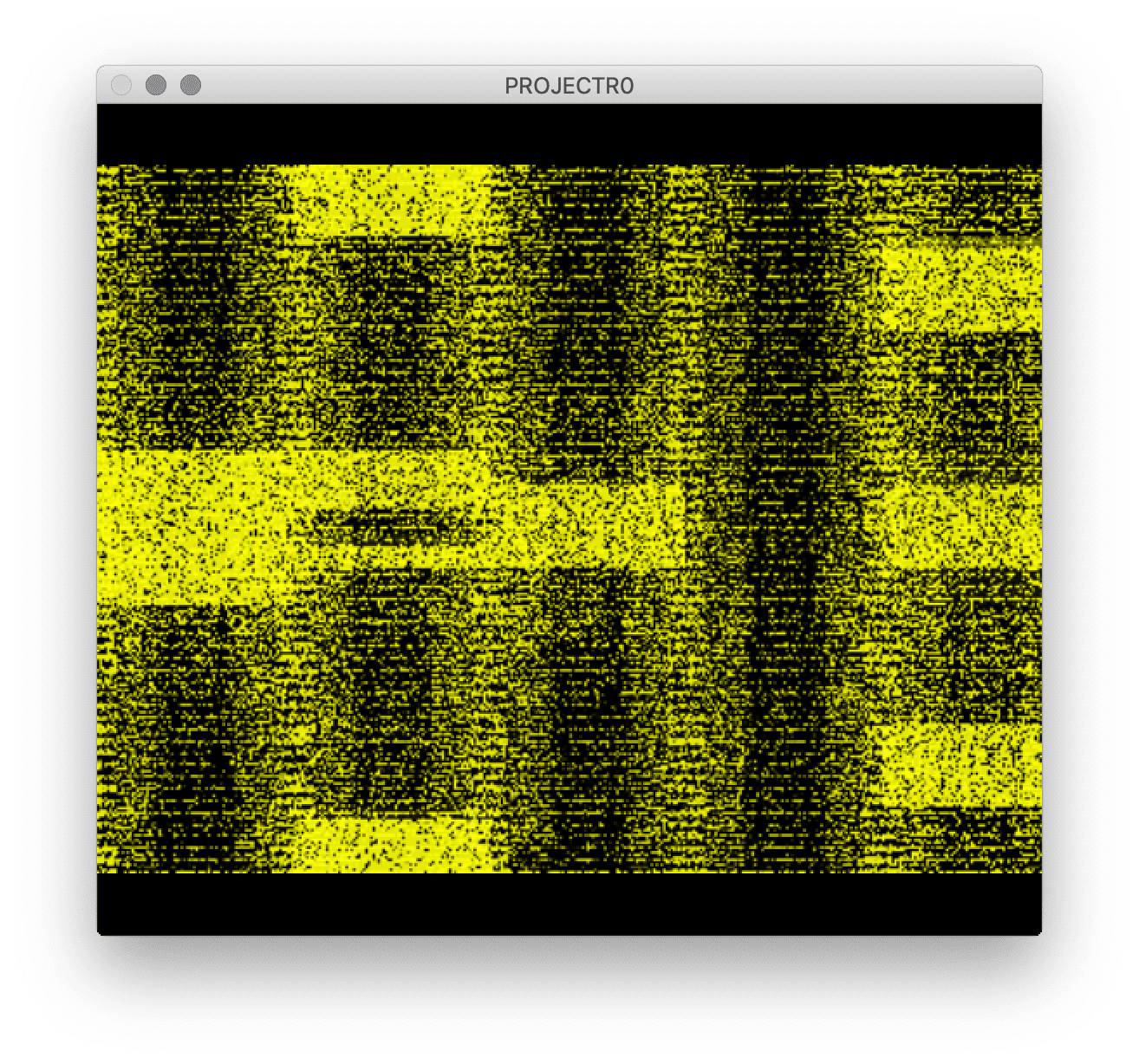

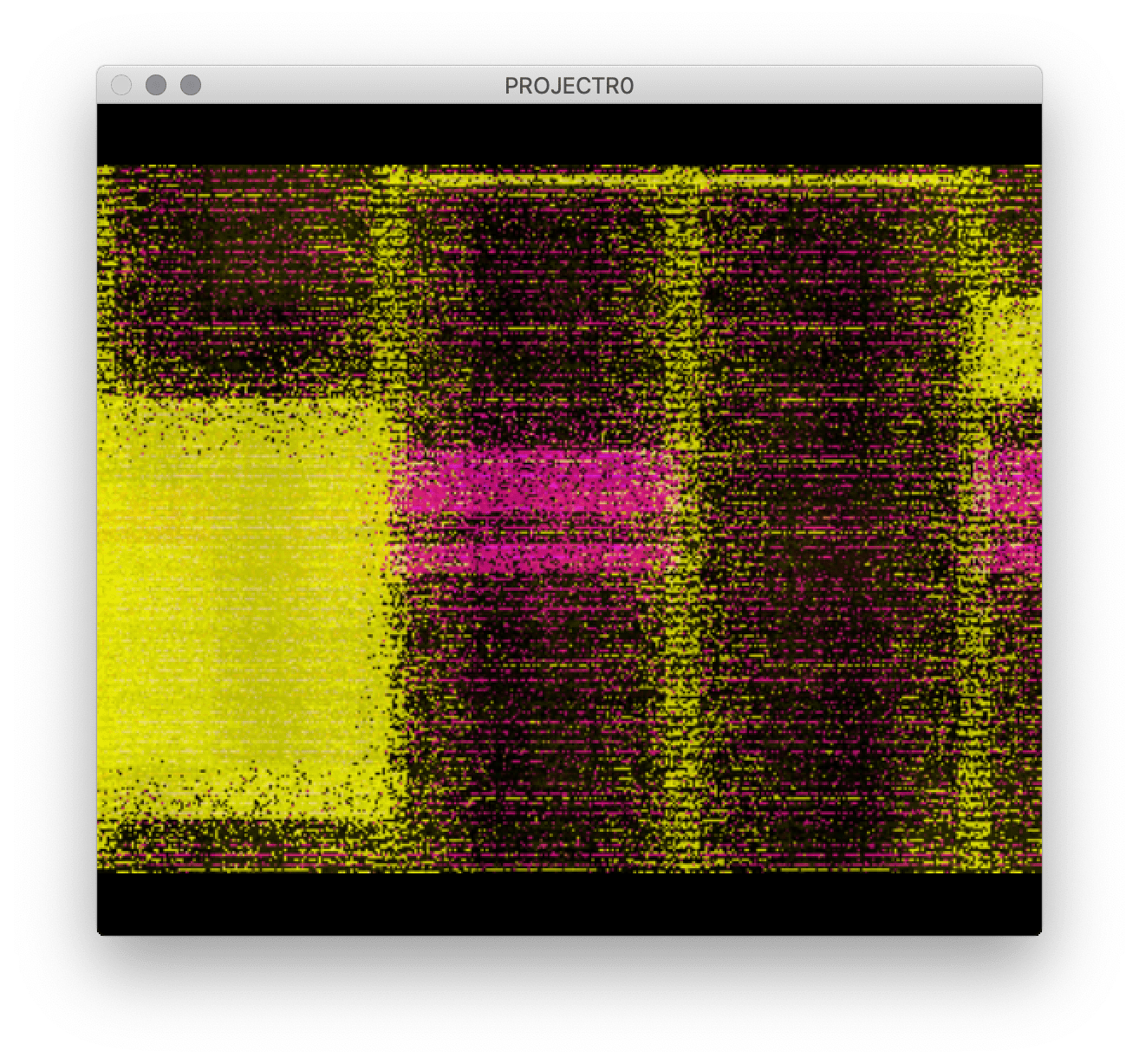

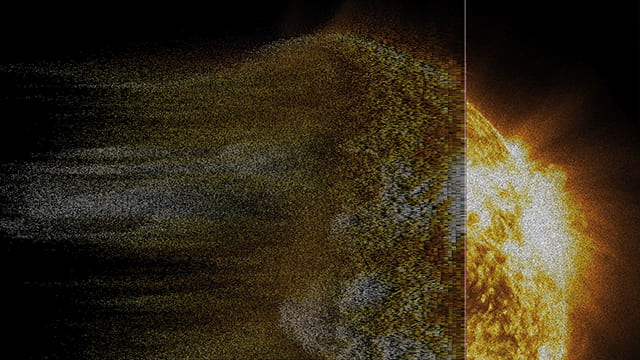

I find myself particularly enjoyed McLaren’s Synchromy so I researched him and his work. McLaren attempt[ed] “a ‘visual translation of the music,'” and what makes his work so special is that he considered films “‘a musical script’ instead of dialogue” (Chan). His creativity and ambition drove him to produce music/sound visualization that we are appreciating now. Synchromy consists of “optically printed vertical bars with horizontal blocks appearing on them” in synchrony with the soundtrack (Valluri). I found out that he composed the soundtrack on the piano first before “print[ing] it onto the optical sound-strip section of 35mm film stock,” then he duplicated the optical sound patterns onto the stock’s visual frame (Valluri).

According to Chan, McLaren was inspired by many of his peers and experimented with developing a deck of pitch cards that worked as a keyboard (which allowed the exact musical pitches of a piano to be photographed on to the soundtrack) with the filmmaker Evelyn Lambart. He marked up a lot on filmstrips with “an array of pencils, pens, brushes, razor blades and other tools” (Chan). By controlling the shape, thickness, and number of slashes, he was able to produce tone, volume and pitch variations (Chan). He arranged these shapes in sequences on the analog optical soundtrack to produce notes and chords, and then reproduced the sequence of shapes and colors in the image portion of the film (Synchromy). The well-syncing visual and sound make audiences feel like “hearing the shape,” or “seeing the sound.” What McLaren had achieved is not only about enhancing the listening/watching experience, but also proving the possibility that sound could be visualized in a smart way — the moving colorful visual actually comes from the soundtrack, “the part of the filmstrip that contains the audio” (Synchromy).

Works Cited

Chan, Crystal. “How to Write a Film on a Piano: Norman McLaren’s Visual Music: Sight & Sound.” British Film Institute, Apr. 2014, www.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/sight-sound-magazine/features/how-write-film-piano-norman-mclaren-s-visual-music.

Millar, Gavin, director. The Eye Hears, the Ear Sees. Internet Archive, National Film Board of Canada, 1970, archive.org/details/theeyehearstheearsees/theeyehearstheearseesreel2.mov.

“Synchromy.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 30 Sept. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Synchromy.

Valluri, Gautum. “The Eye Hears, The Ear Sees: An Investigation into the Visual Influences of Sound in Film.” lafuriaumana.it, www.lafuriaumana.it/index.php/60-archive/lfu-27/507-gautam-valluri-the-eye-hears-the-ear-sees-an-investigation-into-the-visual-influences-of-sound-in-film.