Project Title

侬说啥 (What did you say?)

Conception and Design

When my partner and I were first designing the outline to our project, we knew it had to be simple and easy to understand. Our audience was targeted at young kids so they would be able to learn and understand their native Chinese dialect. We tried to think about how young kids approached learning. From my own experience growing up, I personally remembered loving to make and build things. Whether was with blocks of wood or legos, it was fun for me. Inspired by this, we eventually we decided that a puzzle of China would be a suitable method to help kids understand both the geography and dialect culture at the same time. To make a puzzle, we used Tinkercad online to manually piece together Chinese provinces and then laser cut the file on a wood board. Because the pieces were going to be taken out of the puzzle many times, we wanted a sturdy material so we avoided cardboard. During the process we thought about 3-D printing the map, but because we wanted it to be roughly 15 inches by 15 inches, it would’ve taken days to individually 3-D print separate parts and piece them together later. Below are pictures of the initial base surrounding the puzzle and also the puzzle pieces fitted into the base.

Base of the puzzle by itself

Base of the puzzle by itself

Base with puzzle pieces inside

Base with puzzle pieces inside

Fabrication and Production

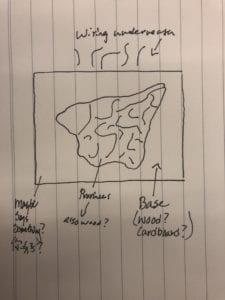

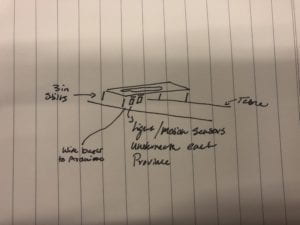

In our initial plan, the puzzle was to be raised 3 inches off the ground and a motion sensor would be put under each province that we selected. It was meant to be a puzzle that one would put pieces into, but we changed it so that pieces would be taken out for the sake of the using sensors underneath. Simplified initial sketches of the design can be found below.

Sketch of the base

Sketch of the base

Sketch including proposed sensors below

Sketch including proposed sensors below

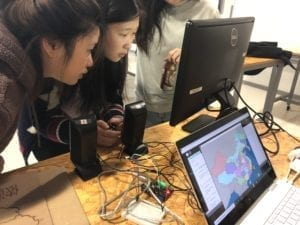

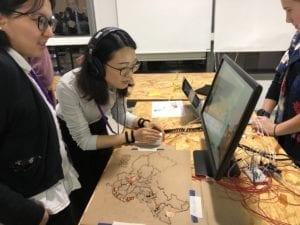

But, when we attempted to raise the puzzle, all of the pieces fell to the ground because they were not fastened in tight enough by themselves. We shifted the idea and placed the puzzle flat onto a cardboard background. Alongside this, we created a map online through processing and arduino which displayed the same physical map. We connected a joystick so that participants would be able to hover over provinces and hear a whisper of the dialect, and thus be incentivized to then pick up the puzzle piece. Unfortunately during user testing, we were not able to connect any sensors to the physical map, so our project was only displayed through the online map. One of the tips was received was to make the joystick easier to use and control our character on screen. So, we changed the initial code to support diagonal movements on screen and improve the fluidity of movement. Another crucial tip we received was a way to involve the physical puzzle pieces of our map in correlation with the online map. Using this advice, we poked holes in the bottom of the cardboard base corresponding underneath each province we had a recording for. We used a wire to connect from Arduino to the map and placed conductive tape over the wire once it was stuck through so just the foil tip ways displayed. We then placed conductive copper tape on the selected puzzle pieces to ensure that the energy from our body would be transferred through the tape on the piece to the wiring below and back into Arduino. This method made it possible to play the native dialect of the province when that particular piece was touched. It was essential to our project and half of it would’ve been incomplete without it. Because it was a last minute adjustment, many of the wires became tangled, but the attempt to beautify the project was our last priority at this design stage. Below are pictures of our project during user testing day.

Participants using the joystick

Participants using the joystick

Conclusions

The goal of my project was to create an educational experience focused on exposing audiences to different Chinese dialects from separate provinces. I think we accomplished this and more by sparking a discussion on how important preserving these dialects are in user testing and presentation days. Within the context of interaction, I think it aligned with my original definition that “Interaction is a continuous conversation between two or more corresponding elements” because it was constant involvement either when using the puzzle, listening to the dialects, or controlling the joystick. The conversational element was representative when the participant would remove a puzzle piece and a dialect would play in response. This call and response constituted for me as a conversation between human and machine. Although, it may not necessarily be continuous because it only works when the participant picks up the puzzle piece. Thus, it isn’t interactive in the sense of a game where one is constantly playing. In our puzzle the subject is always thinking, but not necessarily interacting. Ultimately, our audience didn’t end up picking the pieces up, but rather just touching them. This was because they figured out that the sound would play as long as they touched it. It had the same educational effect as picking it up so this was just a minor diversion from our original intentions. When we concluded that it was not possible to use the light or motion sensors, I felt a sense of defeat. Through the help of professors and our classmates, we strayed from our comfort zone and used conductive tape, a material both my partner and I were not accustomed to working with. While it was indeed difficult to grasp at first, we became aware of the tape’s advantages and it eventually tied our entire project together. The main thing I’ve taken away from this project is that nothing is possible without the help and advice of those around you. Many of the notable alterations in structure came out of comments from our professors and classmates. For this, I am grateful to have such a unique community here at NYU Shanghai that is always willing to help and give feedback at almost any time of the day. Below is a picture of Kevin using our project on the final presentation day and also at the IMA fair.

Presentation Day

Presentation Day