by Sarah Collins-Fattedad

The methods of distributing humanitarian assistance have continuously evolved since the conception of international aid. Today, new and emerging technologies provide an opportunity to improve the efficiency and efficacy of aid delivery. This paper examines the potential for blockchain technology to improve the delivery of humanitarian assistance. (Photo credit: NASA on Unsplash)

Introduction

Humanitarianism entails taking on a daunting, seemingly impossible mission: to provide relief and assistance to affected persons amidst conflicts, crises, and disasters. Humanitarian assistance has continuously evolved since its inception. The adoption and adaptation of emerging technologies remains a vital element for improving the quality and effectiveness of said assistance.

Blockchain is a nascent technology with the potential to positively disrupt our world, similarly to the advent of the internet. This incipient technology possesses unique characteristics that can be used to address the sector’s micro-level issues and macro-level systemic challenges.

So, what are these humanitarian challenges, and how can blockchain be mobilized for impact? This paper will seek to outline the potential impact that the novel technology has on the humanitarian sector by providing a brief history of humanitarianism; by offering an explanation for how blockchain functions, highlighting the key features that may benefit aid delivery; and by inspecting the world’s largest humanitarian blockchain initiative, Building Blocks, as conducted by the World Food Programme (WFP). I will argue that the widespread adoption of blockchain technology can address four vital challenges facing humanitarian assistance: i) the lack of traceability and transparency; ii) incoordination; iii) high costs, particularly transaction costs; and iv) vulnerability to fraud and corruption.

Background & Context

Humanitarian assistance is a catch-all term that covers the broad dedication to, and belief in, the fundamental value of human life. Humanitarianism is generally accepted to have begun with the responses to the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars between 1793 and 1814 (Hardy et al., 2016). In the modern age, it is often understood as the “western crisis response that has evolved from the founding of the Red Cross and the first Geneva Convention over 150 years ago” (PHAP, n.d.). Though lacking a precise definition, as a systemic response to a crisis, humanitarian assistance involves addressing the needs of people affected by conflict, natural disasters, epidemics, and famine. In these crises, humanitarianism focuses on providing basic or immediate needs of assistance and protection guided by four humanitarian principles: i) humanity; ii) neutrality; iii) impartiality; and iv) independence (OCHA, n.d.).

Modern humanitarianism has evolved in many capacities. The tools used, the strategies employed, and the demographics aided have all shifted from solely administering medical care for military personnel to encompassing a wide range of welfare services for all people. With its expansion and the impacts of globalization, humanitarian assistance must continue to innovate and design strategies that employ technological processes of the modern world that were not available over a century ago.

What is Blockchain?

Blockchain technology is a decentralized database that allows for transparent, secure, and immutable information sharing within a network of multiple participants (AWS, n.d.). Blockchain gained its name naturally, as a technology made up of a series of information blocks connected by a chronological chain. As each exchange of information occurs, it is recorded as a block of data. The chain creates a visual history of the movement of an asset, tangible or intangible. A block can record any information of choice, from the most basic — who, what, when, where — and more specific details, such as the condition of the information (e.g., the temperature of the vaccine shipment).

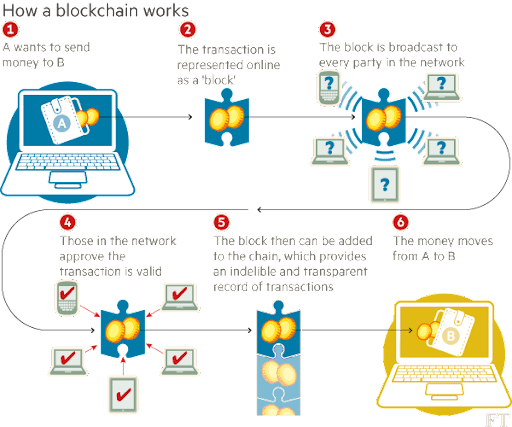

Figure 1: How a blockchain works – Financial Times

The way blocks are created is key to why blockchain enjoys such a high level of security. The majority of the participants, also called nodes, must verify and confirm the accuracy of the new data before a block can be added to the chain. The chain confirms the exact time and sequence of transactions, securely linking all blocks together (IBM, n.d.). This is a much improved and more secure form of accounting relative to a standalone database, spreadsheet, or ledger, where one person can make changes without oversight (Rodbeck and Curry, 2022). Figure 1 illustrates the different stages of blockchain transactions as described above. Each individual part – blocks and chain – makes up the three unique functionalities of blockchain technology: i) the distributed ledger; ii) immutable records; and iii) smart contracts (IBM, 2022).

The distributed ledger is an immutable record of transactions to which all network members have access. Not only is the ledger distributed, as in, all members have their own copy, but it is also decentralized, meaning no central company, institution, or person owns it. Rather, each node of the network assists in the operation of the blockchain. The decentralization of blockchain ensures greater security, as no one point of contact, if subject to a malicious intervention, could bring down the entire ledger (IBM, n.d.). Further, this shared ledger, or history of events, allows for digital transactions to be recorded once, eliminating the duplication of effort typical of traditional business networks, including the humanitarian sector. New York University professor Finn Brunton, Ph.D., describes this concept as “a persistent, transparent, public, [and] a ‘pen-only’ ledger. It is a system where you can add data and not change previous data. It does this through a mechanism for creating consensus between scattered or distributed parties that do not need to trust each other, but trust the mechanism by which their consensus is arrived at” (Wired, 2017).

Immutable records protect the integrity of shared information. No participant can change or tamper with a transaction after it has been accepted and recorded into the shared ledger. If a transaction record includes an error, a new transaction must be added to reverse the error, but both transactions remain visible. This allows the distributed ledger to always have a digital trail, even on incorrect transactions (IBM, n.d.).

Smart contracts are a set of rules stored within the blockchain, allowing for the automatic exchange of information using the IF-THEN-ELSE algorithm. A smart contract defines the conditions necessary before the information is transferred. For example, suppose a donor seeks to provide funds to a humanitarian organization through a smart contract. The donor can set a series of predetermined conditions (e.g., provide photos and statements of needs on the ground) that must be met before the funds are released (IBM, n.d.).

In summary, a blockchain is a series of digital transactions blocked together in a traceable chain. It is a secure, verifiable, quick—updates in real-time—traceable form of exchanging information that promotes transparency and coordination.

Equipped with a better understanding of blockchain, one can begin to understand how humanitarianism could benefit from its inherent features. To further demonstrate the potential of blockchain for humanitarian applications, the following two sections will seek to highlight a World Food Programme (WFP) case study that has successfully employed blockchain technology; and identify how the wide-scale adoption could impact the macro-level challenges facing humanitarian assistance.

World Food Programme & The Building Blocks Project

In January 2017, the WFP launched a blockchain pilot program called Building Blocks, which began as a 100-person pilot in Pakistan. Functionally, Building Blocks is a collection of blockchain nodes independently operated by each participating humanitarian organization. Together, they connect to form a humanitarian blockchain network. This network provides a neutral space to collaborate, transact, securely share information in real-time, and coordinate the delivery of multiple types of assistance, including cash, food, WASH (water, sanitation, and hygiene), and medicine (Zambrano, Young, and Verhulst, 2018). The network is an egalitarian space without a hierarchy of ownership, meaning all member organizations are equal co-owners, co-operators, and co-governors. The overarching objective of the Building Blocks program was to “better protect beneficiary data, control financial risks, improve the cost efficiency by reducing fees to financial service providers, and set up assistance operations more rapidly in the wake of emergencies” (WFP, n.d.).

The Building Blocks project was implemented with great success in Pakistan in 2017. As a result, the program was expanded to aid the influx of Syrian refugees into neighboring Jordan. Here, the sample size grew from 100 people in Pakistan to 10,000, all residing in the Azraq and Za’atari refugee camps (WFP, n.d.). This is where blockchain was used for the first time to deliver aid by purchasing goods from local vendors (UN Women, 2021).

This revolutionary form of aid delivery was made possible through three necessary steps. First, each refugee was provided with a unique identification number linked to biometric data stored in the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) database. Next, refugees received digital funds to purchase goods from pre-approved vendors. Then, by scanning one’s eye, the merchant could authenticate the beneficiary’s identity and process the transaction (WFP, n.d.).

The use of the retinal scan and corresponding unique ID number allowed for every transaction to be securely recorded in the distributed ledger of the Building Blocks blockchain. The WFP used the traceable, verifiable, and secure ledgers to pay the merchants and vendors the corresponding transaction value directly through the WFP’s corporate bank. While the accounting function of blockchain is commendable in and of itself, due to the minimization of bank-to-bank transfers (i.e. WFP did not directly transfer cash to each of the 10,000 refugees but instead in collective lump sums to merchants), the WFP saved 98% of transaction costs (WFP, 2017). To date, the WFP has capitalized on reducing transaction costs, saving approximately $2.4 million. This program in Jordan has again expanded, now in collaboration with UN Women, to assist over 100,000 refugees (WFP, n.d.).

The WFP next turned to implement the Building Blocks programme in Bangladesh, which was experiencing an overwhelming influx of refugees from neighboring Myanmar. To aid the increasing number of Rohingya refugees, Building Blocks was launched in March 2020 in the world’s largest refugee camp, Cox’s Bazar. Here, rather than retinal scans, individuals were given e-vouchers to purchase up to 23 food items from 21 different merchants. The initial sample size was 10,000 people, though the project was quickly scaled to assist 95% of Cox’s Bazar, which includes almost 900,000 individuals (ReliefWeb, 2021). Over 1.3 million transactions took place through the blockchain, resulting in $9.6 million worth of food sold by WFP-contracted Bangladeshi retailers (ReliefWeb, 2021). The combined total of individuals assisted in Jordan and Bangladesh has reached 1 million, with blockchain processing over $300 million of aid.

Beyond its application within refugee camps, the WFP demonstrated the flexibility and adaptability of blockchain technology following the explosion in Beirut, Lebanon, on Aug. 4, 2020. Here, rather than mobilizing Building Blocks for the delivery of aid in refugee camps, the distributed ledger function was used to streamline operations and promote coordination amongst 15 emergency response organizations. The program minimized the duplication of efforts, increased coordination and transparency, and provided families with fast and efficient support. Through Building Blocks, WFP coordinated and distributed $5.6 million of relief aid efficiently (WFP, n.d.).

It is evident through the Jordanian, Bangladeshi, and Lebanese case studies that blockchain technology can be a valuable humanitarian tool. The positive impacts made in micro-level applications of blockchain are profound. However, blockchain has long been heralded as a disruptive technology, meaning it has the potential to significantly alter the way businesses, organizations, or even entire systems operate (Smith, 2022). As successful cases continue to burgeon, the widespread adoption of the technology may have widespread macro-level implications for the humanitarian sector. The following section will seek to identify four vital macro-level challenges for humanitarian assistance that may be positively disrupted and subsequently improved by blockchain technology.

Broader Implications for the Humanitarian Industry

Humanitarianism, by its own nature, takes place in complex, fragile, and often ethically ambiguous environments. As such, realizing secure, coordinated, and traceable aid for many humanitarians sounds utopian. Blockchain cannot fundamentally alter the complex realities on the ground (e.g. refugee warriors, aid blockades, etc.), but it has the potential to impact the four key challenges that confront humanitarian assistance: i) improve traceability & transparency; ii) enable coordination; iii) reduce high costs; and iv) decrease the risks of fraud and corruption.

Traceability & Transparency

The delivery of bilateral, multilateral, or private humanitarian aid is complex as it is not directly issued from donor to recipient. The lack of traceability and transparency of humanitarian assistance is due, in part, to the involvement of many often disjointed and uncoordinated organizations. From the beginning to the end of a donor contribution, it can be unclear how much money was allocated, how many actors were involved, who the end recipients were, and how much of that aid reached the target population (Borton, Brusset, Hallam, 1996). Increasing the traceability and transparency of humanitarian assistance is important to ensure funds reach their target audience in full; to increase accountability for all actors; and to improve data-driven, evidence-based decision-making.

To improve the traceability of resources, transparent and accessible forms of data are required. Data availability improves the effectiveness of humanitarian assistance as it can identify funding inefficiencies and duplicities, or where aid gets lost — more on fraud and corruption later — on both the national and the international level. Access to this data enables more accurate analysis, coordination, and evaluation. The more data humanitarians have, the better resources can be allocated. George Ingram, a senior fellow from the Brookings Institute, highlights that without transparency, humanitarianism lacks the tools to “facilitate collaboration between different finance organizations, to ensure effective use of resources, and to hold institutions accountable” (Ingram, 2018).

Blockchain technology allows funds from private donors, governments, or NGOs to be traceable at every transactional step. Further, a blockchain-based humanitarian aid system would allow for greater donor trust that resources will reach the target population. Further, trust is strengthened with smart contracts, where donors can determine a set of conditions that must be achieved and verified before funds are released. Through the features of blockchain that promote traceability and transparency, not only can trust be gained, financial inefficiencies mitigated, and accountability held, but donor contributions could increase in the future (Bricout and Aurez, 2020).

Coordination

In parallel, the lack of coordination within the humanitarian system and between stakeholders needs to be addressed. As vividly described in the Crisis Caravan, the increasing number of NGOs and “MONGOs” (My Own NGO) in the field is a coordination nightmare. In his 2007 book Giving: How Each of Us Can Change the World, former U.S. president Bill Clinton noted this trend by stating that there has been an “explosion of private individuals who devote themselves to a good cause” and an “unprecedented democratization of charity” (Clinton, 2014). In terms of sheer numbers, in the U.S., the Internal Revenue Service grants tax exemptions to an average of 83 new charities a day, adding to the total of 150,000 other charities already in existence (Polman, 2011).

Blockchain has the potential to revolutionize humanitarianism by enabling widespread coordination. A blockchain-based humanitarian aid system can offer a unique platform that increases the visibility of each organizations’ operations, centralizes humanitarian services for recipients, and encourages communication among organizations. A positive by-product of improved communication is its impact on preventing administrative redundancy and duplication of efforts. It also allows for policy harmonization and the identification of policy gaps by revealing to all stakeholders the organizations helping a given population and with what resources (Bricout and Aurez, 2020).

Costs

Humanitarian assistance is expensive. Billions of dollars flow along a supply chain, with various stakeholders tasked with distributing the resources to their final target population. At each stage, the organizations involved are charged transaction fees by financial institutions. The precise percentage each organization charges is remarkably difficult to uncover. The Feinstein International Center projects that “U.N. agencies are thought to regularly retain between 7% and 13%… NGOs may retain anything from 3% to 15%” (Walker and Pepper, 2007).

Since January 2022, the Government of Canada has committed $320 million in humanitarian assistance to various organizations to respond to the impacts of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (Global Affairs Canada, n.d.). If the Government of Canada sought to allocate $1 million of that to the U.N., for this thought experiment, let us assume the transaction passes through three nodes: first, the U.N., then a regional NGO, ending with the local partner distributing the funds to the beneficiaries in Ukraine. If each node billed a 7% transaction fee, by the time it reaches the beneficiaries, the original allocation of $1 million dwindles to $804,357, resulting in a total transaction cost of $195,643, or 19.6%, of the overall allotment.

The scale of global humanitarian funding further exacerbates the compounding effect of transaction fees on humanitarian resources. According to the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Assistance (OCHA), as of Oct. 31, 2022, the total reported humanitarian funding for this year has reached $2.83 billion (OCHA, 2022). If we continue the thought experiment, applied to the total global funding, over $553 million would be lost to transaction costs. It is essential to highlight that the overhead costs of humanitarian organizations will never be eliminated entirely. Although, as seen in the WFP Building Blocks program, utilizing blockchain can reduce the reliance on financial institutions or “middlemen.” Thus, the reduction in transaction costs of up to 98% allows for the reinvestment of $2.6 million for furthering humanitarian objectives, such as utilizing funds to purchase more food assistance or educational training for humanitarian personnel. If this efficiency is scaled to the global level, it will allow millions of dollars of aid to be reinvested into people and not the process (WFP, n.d.).

Fraud & Corruption

Fraud and corruption remain as under-researched issues within humanitarian assistance. This is partly due to the difficulties surrounding the lack of traceability, as previously discussed. The other part, as described by Paul Harvey from Humanitarian Outcomes, is that “humanitarian aid agencies devote significant time, energy, and resources to internal efforts to combat corruption, but remain reluctant to openly discuss and share learning due to fears that talking about corruption could undermine public support” (Harvey, 2015). Moreover, while there is a lack of concrete data on how much humanitarian assistance is siphoned off, it is nonetheless a substantial systemic challenge (Bricout and Aurez, 2020).

Another benefit of blockchain’s traceability and transparency function would be its ability to strengthen anti-fraud and anti-corruption efforts. Once validated and added to the blockchain, the immutable blocks ensure that funds do not end up in the wrong hands. Instead of cash, which could be used to purchase weapons or armies, blockchain ensures that aid is used for its original purpose (Bricout and Aurez, 2020). As seen in the WFP project, moving away from cash transfers to digital e-vouchers allows humanitarians to structure and trace how aid is spent. Therefore, blockchain will securitize humanitarian information and resources, or at the very least, make them tamper-evident. This can reduce the likelihood of the exploitation of financial aid through fraud and corruption.

Conclusion

Blockchain has the potential to positively disrupt the humanitarian system. The early and scalable success of Building Blocks demonstrates blockchain’s impact and potential future value in the humanitarian space. The continuous and increasing adoption of blockchain may begin to address the challenges, as described above, of traceability, transparency, coordination, high costs, and corruption. Nevertheless, blockchain is not an all-encompassing panacea. A plethora of challenges lay ahead of its widespread adoption and implementation. While beyond the scope of this paper, these challenges include internet connectivity, digital privacy concerns, digital illiteracy, and even cultural acceptance of the technology by both humanitarians and beneficiaries.

Blockchain and its application to humanitarianism is still in its infancy, and more research, pilot projects, and case studies must be done. All parties involved must remain vigilant to ensure that all human and digital rights are promoted, not violated, using new and emerging technologies. Blockchain, with its promise to improve humanitarian assistance, must be accompanied by a human rights framework to ensure equality for all. As U.N. General Assembly President Csaba Kőrösi emphasized, “Digital technologies are a game-changer… Yet, we will not see the full benefits of the digital age if we do not address the digital divide and ensure equitable digital empowerment for all” (UN News, 2021).

*******

Sarah Collins-Fattedad is a second-year master’s student at NYU’s Center for Global Affairs with a concentration on International Development and Humanitarian Assistance. Her academic foci include the intersection of gender and development as well as the humanitarian-development nexus. Prior to and throughout her NYU experience, Sarah worked for the United Nations and the United Nations Development Programme.

Bibliography

“Blockchain Against Hunger: Harnessing Technology in Support of Syrian Refugees.”

World Food Programme. United Nations, May 30, 2017. https://www.wfp.org/news/blockchain-against-hunger-harnessing-technology-support-syrian-refugees.

“Blockchain Expert Explains One Concept in 5 Levels of Difficulty.” Wired. Conde Nast, 2017. https://www.wired.com/video/watch/expert-explains-one-concept-in-5-levels-of-difficulty-blockchain.

Borton, John, Emery Brusset, and Alistair Hallam. “Humanitarian Aid and Effects – OECD.” The International Response to Conflict and Genocide: Lessons from the Rwanda Experience. OECD. Accessed November 2022. https://www.oecd.org/derec/50189439.pdf.

Bricout, Aymeric, and Vincent Aurez . “2020 Blockchain for Humanitarian Aid Systems.” Frankfurt School Blockchain Centre. Frankfurt School of Finance and Management, August 2020. http://explore-ip.com/2020-Blockchain-for-Humanitarian-Aid-Systems.pdf.

“A Brief History of Drones.” Imperial War Museums. Accessed November 2022. https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/a-brief-history-of-drones#:~:text=The%20first%20pilotless%20vehicles%20were,first%20flew%20in%20October%201918.

“Building Blocks.” WFP Innovation Accelerator . World Food Programme. Accessed November 2022. https://innovation.wfp.org/project/building-blocks.

“Building Blocks: The Future of Cash Disbursements at the World Food Programme.” WFP Innovation Accelerator . World Food Programme. Accessed November 2022. https://unite.un.org/sites/unite.un.org/files/session_2_wfp_building_blocks_20170816_final.pdf?source=post_page—————————.

“Child given World’s First Drone-Delivered Vaccine in Vanuatu.” UNICEF, December 18, 2018. https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/child-given-worlds-first-drone-delivered-vaccine-vanuatu-unicef.

Clinton, Bill. Giving: How Each of US Can Change the World. London: Cornerstone Digital, 2014.

“Don’t Let the Digital Divide Become ‘The New Face of Inequality’.” United Nations News. United Nations, April 21, 2021. https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/04/1090712.

“Economic, Humanitarian, Development Assistance and Peace and Stabilization Support– Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine.” Global Affairs Canada. Government of Canada, November 18, 2022. https://www.international.gc.ca/world-monde/issues_development-enjeux_developpement/response_conflict-reponse_conflits/crisis-crises/ukraine.aspx?lang=eng.

“Global Humanitarian Overview 2022.” ReliefWeb. OCHA, November 7, 2022. https://reliefweb.int/report/world/global-humanitarian-overview-2022-october-update-snapshot-31-october-2022.

Hardy, Anne, John Manton, Erin Lafferty, and Karl Blanchet. “The Evolution of Humanitarianism throughout Historical Conflict.” Centre for the History of Public Health. London School of Hygiene & Topical Medicine, October 31, 2916.

https://www.lshtm.ac.uk/research/centres/centre-history-public-health/news/2017-2.

Harvey, Paul. “Evidence on Corruption and Humanitarian Aid.” ReliefWeb. CHS Alliance, December 4, 2015. https://reliefweb.int/report/world/evidence-corruption-and-humanitarian-aid.

“Humanitarianism.” Professionals in Humanitarian Assistance and Protection (PHAP). Accessed November 2022. https://phap.org/PHAP/PHAP/Themes/Humanitarianism.aspx.

Ingram, George. “How Better Aid Transparency Will Help Tackle Global Development Challenges.” Brookings. Brookings, March 9, 2022. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2018/06/21/how-better-aid-transparency-will-help-tackle-global-development-challenges/.

Polman, Linda. The Crisis Caravan: What’s Wrong with Humanitarian Aid? New York: Picador, 2011.

Rodeck, David, and Benjamin Curry. “What Is Blockchain?” Forbes. Forbes Magazine, October 14, 2022. https://www.forbes.com/advisor/investing/cryptocurrency/what-is-blockchain/.

Smith, Tim. “Disruptive Technology: Definition, Example, and How to Invest.” Investopedia. Investopedia, September 21, 2022. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/d/disruptive-technology.asp.

“UN WOMEN-WFP BLOCKCHAIN PILOT PROJECT FOR CASH TRANSFERS IN REFUGEE CAMPS Jordan Case Study.” UN Women / WFP, January 2021. https://jordan.unwomen.org/en.

“Vanuatu: Who and UNICEF Estimates of Immunization Coverage: 2021 Revision.” UNICEF. Vanuatu Ministry of Health, July 7, 2022. https://data.unicef.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/vut.pdf.

Walker, Peter, and Kevin Pepper. “Follow the Money: A Review and Analysis of the State of Humanitarian Funding .” Feinstein International Institute. Tufts University, June 2007. https://fic.tufts.edu/assets/Walker-Follow+the+Money-A+Review+and+Analysis+of+the+State+of+Humanitarian+Funding.pdf.

“WFP Bangladesh: Rohingya Refugee Response Situation Report.” ReliefWeb. World Food Programme, March 18, 2021. https://reliefweb.int/report/bangladesh/wfp-bangladesh-rohingya-refugee-response-situation-report-47-february-2021.

“What Are Humanitarian Principles?” The Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Assistance (OCHA), July 2022. https://www.unocha.org/sites/unocha/files/OOM_Humanitarian%20Principles_Eng.pdf.

“What Are Smart Contracts on Blockchain?” IBM. IBM Blockchain. Accessed November 2022. https://www.ibm.com/topics/smart-contracts.

“What Is Blockchain Technology? .” IBM Blockchain. IBM. Accessed November 2022. https://www.ibm.com/topics/what-is-blockchain.

“What Is Blockchain.” Amazon. Amazon Web Services (AWS). Accessed November 2022. https://aws.amazon.com/what-is/blockchain/.

Wild, Jane, Martin Arnold, and Philip Stafford. “Technology: Banks Seek the Key to Blockchain.” Financial Times, November 1, 2015. https://www.ft.com/content/eb1f8256-7b4b-11e5-a1fe-567b37f80b64.

Zambrano, Raul, Andrew Young, and Stefaan Verhulst. “CASE STUDY: Connecting Refugees to Aid through Blockchain Enabled ID Management: World Food Programme’s Building Blocks.” Block Change. GovLab, October 2018. https://blockchan.ge/blockchange-resource-provision.pdf.