Haiti’s Folk Revolution

Tracing the international proliferation of Haitian folk music…

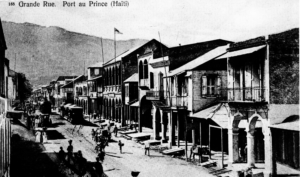

The story of Haiti’s folk music and radicalism have been crucially linked since at least the Haitian Revolution, when at Bwa Kayiman a religious ceremony, notably accompanied by music, ushered in a new chapter in the fight for freedom and equality. Over a century later, the United States Occupation of Haiti from 1915-1934 would act as the next major catalyst for a shift in Haiti’s cultural politics. On 28 July 1915, the U.S. Marines invaded and soon after established a neo-colonial state concerned more with protecting the assets of the National City Bank of New York (now CitiBank) than with establishing democracy or the rule of law. Prior to the occupation, most elite Haitians sought to emulate European standards of art, literature, and music, while the rural majority maintained a complex and rich set of African-derived cultural practices since their emancipation during the Haitian Revolution. The occupation forced the elite to reevaluate their cultural orientation, and they increasingly found validity in religious and musical forms that were previously viewed with derision or embarrassment. (1) Image from Georges Corvington, Port-au-Prince au cours des ans.

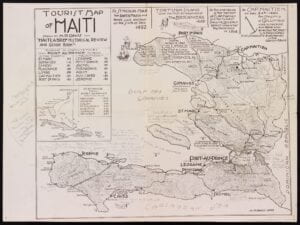

Rural Haiti was the center of armed struggles between U.S. Marines and guerrilla insurgents known as “cacos.” A series of vicious campaigns from 1915 to the early 1920s devastated the Haitian countryside, with Marines unleashing indiscriminate violence against combatants and civilians alike. After the assassination of the last major rebel leader Charlemagne Peralte and the end of the “Caco wars,” U.S. officials prioritized road building projects to penetrate the interior in order to subdue any future revolts. After insurgents were eradicated from the countryside, Haitians continued to reference them in folk song, but now referring to American Marines as “cacos in Khakis.” (2) This photo is of the construction of the road from Lascohabas to Hinche, an area where anti-occupation insurgents were extremely active. Image accessed from the Digital Library of the Caribbean.

Following the period of armed struggle, the 1920s was a decade of increasing protest against imperialism in Haiti. From these protests the international circuits of the popular folk revolution emerged. Born in collaboration with many of the leading figures of the Harlem Renaissance, Haiti’s Patriotic Union became a central organization in anti-occupation efforts. Not surprisingly, the organization was led by vocal proponents of Haitian folk culture, including Georges Sylvain and Jean Price-Mars. They helped organize major protests during the U.S. Senate inquiry into the abuses of the earlier anti-insurgent campaigns. (3) While the Patriotic Union was not able to end the occupation with the Senate Inquiry, it put a spotlight on Marine violence and helped usher in a new period in cross-class and international cooperation, without which the spread of Haiti’s folk music would not have been possible. Image from Georges Corvington, Port-au-Prince au cours des ans.

The Damien Agricultural School (above) was the site of a major student strike in 1929 that exploded into a nationwide general strike. The agronomist Nicholas Schiller and later the writer, ethnographer, and communist Jacques Roumain, along with a host of other young Haitian radicals, took the lead as events escalated. In accounts of the protest, music played a crucial role, as students marched, drummed, and chanted their grievances to the beat. (4) The collective actions of students, workers, and radicals helped bring about the end of the U.S. occupation in 1934. Photographed by George E. Simpson in 1937, image accessed from the Smithsonian Online Virtual Archives.

Toward the end of the occupation and into the post-occupation years, a period known as “Second Independence,” Haiti attracted a sizable number of American folklorists and anthropologists, including Melville and Frances Herskovits, Harold Courlander, Zora Neale Hurston, Alan Lomax, Katherine Dunham, and George E. Simpson. Prior to their arrival, racists stereotypes often dominated American interpretations of Haitian culture. This new group instead posited that Haiti’s folkways were rich and complex, a culture not determined by race, but rather by specific historical and social origins. For these social scientists, the tradition of Haitian folk music served as evidence that Haiti was not culturally backward or frozen in time, but rather was at the forefront of cultural change. (5) During their fieldwork, all of these American folklorists and anthropologists spent time in the town of Plaisance, and likely heard the drummers above, photographed by Simpson in 1937, image accessed from the Smithsonian Online Virtual Archives.

Melville and Frances Herskovits conducted fieldwork in Haiti during the summer of 1934, right as the U.S. occupation was coming to a close. In his monograph, Life in a Haitian Valley, he wrote that “while the intervention of the United States has caused significant changes in the larger aspects of Haitian economy and in the political life of the Republic as a whole, yet as concerns the inner life of the people of this valley it seems to have passed without any discernible effects.” When Herskovits encountered music in Haiti, and in particular the drumming, he commented in his diary about its similarities with styles in Dahomey in West Africa. (6) Image accessed from the New York Public Library.

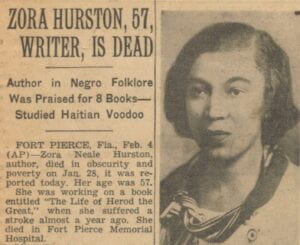

Zora Neale Hurston emerged from the Harlem Renaissance as a veritable pioneer in both fiction and the study of folklore. In 1936-1937, she went to Haiti to do fieldwork. (7) Photographed by Alan Lomax, in Haiti. Images accessed from the Library of Congress.

Alan Lomax was a trailblazer in the world of folklore and ethnomusicology. Notably, in his first decade as a collector, he traveled to Haiti and described it as “the richest folk-song field I know.” Under the auspices of the Library of Congress, the young Lomax produced over a thousand recordings of Haitian music ranging from the religious, mundane, and profane that constitutes an invaluable audible archival glimpse into how 1930s Haiti sounded. (8) Images accessed from the Library of Congress.

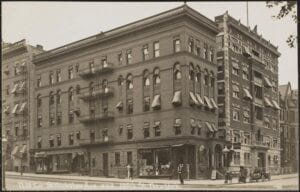

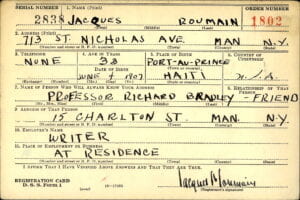

The close of the 1930s saw increasing exchange of radical thoughts on politics and culture between Haiti and New York City. Black intellectuals including Arthur Schomburg, Langston Hughes, and Walter White all befriended Jacques Roumain while staying in New York in the 1930s and 1940s. Roumain spent much of his time in New York searching for financial support for the Haitian Communist Party, which he founded in 1934. He also attended anthropology courses at Columbia University around the same time as Alan Lomax in 1939, though both would stop attending classes by the end of the semester. (9) Above is a photo of the intersection of 145th Street and St. Nicholas Avenue in Upper Manhattan. Roumain lived in one of the brownstones on the right of the photo. Images accessed from the Museum of the City of New York and the National Archives via Ancestry.com.

Notes:

(1) Peter James Hudson, Bankers and Empire (2017), 81-116; Imani D. Owens, “Beyond Authenticity: The U.S. Occupation of Haiti and the Politics of Folk Culture,” Journal of Haitian Studies vol. 21 (2015): 350-370.

(2) Harold Courlander, A Treasury of Afro-American Folklore (1976), 56.

(3) Georges Sylvain, Dix années de lutte pour la liberté, 1915-1925 vol. 2 (n.d.).

(4) “Summary of Strike from October 31, 1929,” Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, record group 127, entry 241, box 5, folder “Compendium of Info on the Garde,” National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

(5) See Melville J. Herskovits, Life in a Haitian Valley (1937); Zora Neale Hurston, Tell My Horse (1938); Alan Lomax, “Haitian Journey,” Southwest Review vol. 23 (1938); Harold Courlander, Haiti Singing (1939); and Katherine Dunham, Island Possessed (1969).

(6) Herskovits, Life in a Haitian Valley (1937), 10; and Herskovits “Diary-Haitian Field Trip, 1934 (june-aug),” Melville J. and Frances Herskovits Collection, box 14, folders 68, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library.

(7) See Leigh Anne Duck, “‘Rebirth of a Nation:’ Hurston in Haiti,” Journal of American Folklore vol. 117 (2004); Kevin Meehan, “Decolonizing Ethnography: Spirit Possession and Resistance in ‘Tell My Horse,’” Obsidian vol. 9 (2008); Many A. Renda, Taking Haiti (2001), 288-300; Ifeoma Kiddoe Nwankwo, “Insider and Outsider, Black and American: Rethinking Zora Neale Hurston’s Caribbean Ethnography,” Radical History Review vol. 87 (Fall 2003); and Charles King, Gods of Upper Air (2019), chapters 9 and 12.

(8) Quoted in John Szwed, Alan Lomax (2010), 97; also see Gage Averill, “Ballad Hunting in the Black Republic: Alan Lomax in Haiti, 1936-37,” Caribbean Studies vol. 36 (2008); Alan Lomax in Haiti, compact disc, 1-10 vols. (2009).

(9) Léon-François Hoffmann, “Chronologie,” in Jacques Roumain: Œuvres Complètes (2018), 1521; Szwed, Alan Lomax, 140-142.