The inspiration for this project largely comes out of another project I did last year while studying abroad in Berlin, Germany. While there, I became fascinated by how history manifests itself in the public space of the city. What really caught my attention in particular, was the Holocaust Memorial. As a Jewish American, I was initially annoyed by the way many people interacted with the space. The memorial itself is meant to be interactive. Designed by Peter Eisenman, the memorial is made of 2,7000 concrete slabs that only differ in height. They are arranged in a grid, and people are able to walk through the grid any way they want experiencing “the wave like form differently from each different position.” I kept on wondering if is supposed to be interactive, what happens if people interact with the place in the “wrong” way? Can there be rules for a public space, even if it is a place meant for mourning or remembrance?

As this semester progressed, I began thinking more about how these themes relate to the 9/11 Memorial in New York. More so than the Holocaust Memorial, the 9/11 Memorial has much more personal significance to me. I was seven years old on September 1, 2001, living about 30 miles north of New York City. The day itself is one of my earliest memories. The teachers in my elementary school were not allowed to tell us what was going on, and as the morning went on, more and more parents arrived at the school to get there kids. I remember when my babysitter finally arrived, my brother, sister and I were confused because we weren’t allowed to get ice cream from the truck we usually got it from after school. When we arrived at home, footage of the attacks were playing on the TV in our living room. My brother and his friend who came over said something along the lines of “woah cool,” thinking the footage was from a movie, at which point, my mom informed us that the attacks were real. My only other memory of that day is trying to go into my parents room where my dad was after getting home from his office a block away from the World Trade Center. The door was locked and my mom told me I couldn’t go in for a little while. I think I remember that day less because I was afraid, but because all of the adults in my life were acting in a way that I was too young to understand.

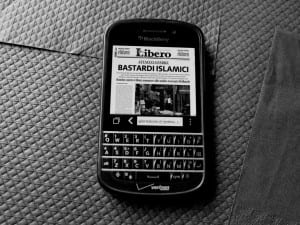

Like much of my generation, I grew up in a world that was completely changed by 9/11, and the War on Terror that fallowed. Maybe if I was 10 years older, it would be easier for me to grasp how the world has changed because of the attacks. In This Muslim American Life, Moustafa Bayoumi describes a “War on Terror culture”. He writes, “War on Terror culture means that the 9/11 Memorial, supposedly dedicated to ending intolerance and ignorance, offers pamphlets in nine languages but bizarrely not Arabic, and the 9/11 tour concludes with a film considered by many to be inflammatory toward Islam” (13) The film Bayoumi describes is called The Rise of Al Qaeda, and before the museum opened, the film was shown to a group of interfaith clergy. The only imam in the group, said of the film, “Unsophisticated visitors who do not understand the difference between Al Qaeda and Muslims may come away with a prejudiced view of Islam, leading to antagonism and even confrontation toward Muslim believers near the site.”, while the museum defends the film, saying it was created with the advisement of experts on Islam and terrorism (NY Times). Like most memorials, the 9/11 memorial is not a place without politics, and I was interested in how the politics of the memorial affect the way people interact with space, if it did have any effect at all.

Another interesting perspective on the 9/11 memorial comes from Marita Sturken, in her book Tourists of History: Memory, Kitsch and Consumerism from Oklahoma City to Ground Zero. According to Sturken, the 9/11 memorial has become a place of sentiment and kitsch. The kitsch she describes is not something shown in the design of the memorial itself, but rather, in the souvenirs you can buy at the memorial or the nearby museum shop. She writes, “A kitsch image or object not only embodies a particular kind of prepackaged sentiment, but conveys the message that this sentiment is universally shared, that it is appropriate, and importantly, that it is enough. When this takes place in the context of politically charged sites of violence, the effect is inevitably one that reduces political complexity to simplified notions of tragedy.” (26) She believes that the 9/11 memorial (and its entire complex, including the Freedom Tower) is less about a place of redemption, and more one of mourning and patriotism. This is a problem, because it portrays the acts in a watered down way.

Before taking photos at the memorial, I decided to see how Magnum and VII members photographed the site. One photo by Susan Meiseles, shows a group of businessmen and women observing a moment of silence at the memorial on September 11, 2015. They are all wearing varying shades of gray suits with the hands folded in front of them. Another photo by Ron Haviv shows a Pennsylvania State Constable saluting an American flag on the 10th anniversary of the attacks with a cigar hanging from his mouth. A third by Eli Reed shows people watching the memorial ceremony on the one year anniversary of the attacks. Many people are holding American flags and have camera straps hanging from their necks. The last photo reminded me of one of the installations at the recent Laura Poitras exhibit at The Whitney Museum, which shows people watching ground zero the day after the attacks in slow motion. These three photos, in varying ways show patriotism and sorrow. They also reverse the gaze of the normal way we see ground zero, and the memorial built in its place in images. Instead of looking at the memorial itself, we are looking at people looking at the memorial. However, I was interested in how people would act at the memorial on every other day. My photos show people at the 9/11 memorial on April 28, 2016.

Recent Comments