A Blurry Image of Women In War Photography

Throughout the semester, we looked at many images while still studying the photographer’s personal input and perspective on their work. However, this method does not always reflect reality. In an everyday life situation, one would see the image in a magazine without, most of the time, really knowing any background information about either the photographer or the story behind the shot. Once the picture the attention shifts entirely to the subject of the photo. This makes the art of photography very challenging for photojournalists. When studying Martin Parr fro instance, I found it extremely frustrating to read that he “does not talk about his photos, (he) just does them”. However, Parr in a way manages, by carrying this philosophy reflects as much as possible the reality of a viewer’s experience when looking at art or photography. Once a photo is published, I believe that it doesn’t belong entirely to its photographer anymore as it is subject to the viewer’s own interpretation and critical eye. This also makes photography extremely challenging as images can be taken out of their context and used wrongly. As Ashley Gilbertson said about his Whiskey Tango Foxtrot images, “some people saw them as pro-war photos, some others saw them as anti-war images”.

This ultimately led me to think about Ron Haviv’s thought about photojournalism: “I suddenly understood the power of photojournalism. I realized this wasn’t about me, it was about the people I was photographing.”

This idea of the forgotten really intrigued me and I started to ask myself who might be the most ‘forgotten ones’ in photojournalism. The first answer that I could think of was women. Even though we saw a lot of female subjects photographed in fashion photography and war photography; we did not talk about many female photographers. And, especially, I found it interesting to study the place of women photojournalists in war photography. Our societal preconceptions usually lead us to associate war with masculinity, a man’s business. So, what is the place of women in war photography? Are they only bound to be the subject of the images in order to create touching shots?

But as I started researching female photojournalists, I was positively surprised by my findings. Recently, to celebrate its 125th anniversary, National Geographic Magazine published a retrospective of the most influential images of the past century or so. And I was stunned to see that many of those iconic images were taken by female photographers. So, why don’t we hear more about female photographers who produce powerful and influential work in an industry known for being dominated by men?

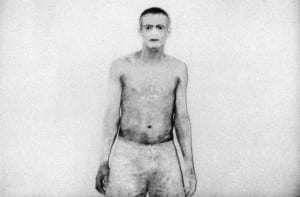

After talking to one of my friends about it, he told me something that really lead me to study specifically the place of female photographers in war photography: “A dead body on the sidewalk is a dead body. It should be covered the same way by a man or a woman. We’re all human, we should see and be affected by a dead body the same way.” Do female photographers think about this the same way?

There are only about a dozen female war photographers actively working today so this made my research a little bit difficult and, I found that this very small number tends to create skewed and biased results. I realized that it is very important to take this into consideration for our analysis. But, why are there so few female war photographers? Well, I found that a very primitive sexism is still present in the industry even though some women broke barriers and opened doors for new generations.

First, being a photojournalist covering armed conflict is believed to be ‘too hard’ for women. They are seen as physically less strong than men and psychologically too emotional.

Also, the lifestyle of a war photographer is considered unsuitable to a woman as it requires a huge flexibility for traveling. Our society’s stigma tends to expect women to have children and to take care of them. Socially it is also more acceptable fir a man to prioritize his career over his family than it is for a woman.

I also found that some cultures see women as ‘less capable’ intellectually than men.

And finally, the most common one was that covering a conflict is ‘too dangerous’ for women. To this preconception, the former present of AP photography says very rightfully answered that “bullets are not sexist”. However, it has been proven that women are more prone to be victims of violence.

These stereotypes cause female photographers to sometimes not feel welcomed or accepted by the male figures in a war zone.

But, what do those female war photographers have to say? After studying about the society’s stigmas about female figures in a war zone, I was extremely surprised to read those women’s testimonies. Most of them said that their gender has turned out to be an advantage in their male-driven industry. But, I really am having trouble grasping this concept. I believe that their gender has been a supplementary obstacle that the first women entering the industry had to overcome.

However, after reading many testimonies, watching dozens of interviews and documentaries; I started to believe them. And I think thats exactly what they were aiming to do. They want to inspire and make us believe in their strength. And that just takes us right back to the primitive sexism in which women have to prove themselves more than men do.

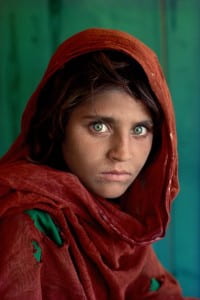

However, I found it very interesting to see that female photographers are important actors in the Muslim world where religious rules and the culture is very different from the American democratic ideals. They are mentioned many times as key in the coverage of many conflicts in the Middle East. What inspired me to look at the place of female photographers in the Muslim world was the story behind Steve McCurry’s icon shot of the Afghan refugee that made the cover of National Geographic. Years after taking the first portrait that became worldwide famous, McCurry went back to Afghanistan in the hope of finding the girl and taking another portrait of her. After weeks of research, he finally found her. The only last obstacle that stood in front of McCurry was that, as a man, he could not enter the house. Therefore, he had to get a woman on site just to be able to talk to the Afghan girl. Another issue was that she could not be seen by a man without her head piece, even less get photographed without it. But, after long negotiations with the woman intermediary, McCurry finally was able to take that shot. And this is when it all made sense to me. This is when I understood that yes, in the Muslim world, being a female is an advantage. After doing some research on how women are perceived in a war zone by the civilians there, I found out that women are seen as less threatening than men.

But most importantly, in the Muslim world, women have access to houses and a family’s intimacy when as men don’t. As Lindsey Addario, war photographer published in National Geographic said, “we already have one foot in the houses”. This indeed represents a huge advantage for female photographers.

Also, some say that women create a very unique bond with their female subjects, just like man photographers do with their male subjects. I am not quite sure that I agree completely with this statement, just because it is mostly said by the female photographers themselves. I had a really hard time figuring out the reality of female photographers’ situation and experiences while covering a conflict. And this confusion is what led me to think about my project. The public does not truly know how those female photographers live while doing their job. This confusion creates a distance between the public and the photographer, leading to a shattered trust. For instance, when an incident happens just like it did in Lybia where a group of photojournalists were kidnapped and kept hostage for a while. One of those was Addario and the public’s reaction was mainly outrage: “Why was a woman involved in this? Why would Time magazine send a woman over there where women’s rights are violated?” But again, this assumption about women’s rights in Middle Eastern countries is thought from an American point of view. So, I have to admit that this was a hard subject, and still today I am not sure how to treat it. I got confused and lost many times during my research, maybe even got brainwashed by reading articles and watching interviews in which women are claiming that being a female is a huge advantage. I got inspired, for sure, but my judgement was biased. I did not read about any men photographers’ point of view on this matter and, when I did, they were just extremely politically correct, like “she proved that she was talented enough, so she got the job”. The American democratic system and ‘liberalism’ in place does not in reality allow either men or women to tell us truly what they think in fear of getting shamed or judged for their words.

So, clearly there is a lack of communication and honesty towards the public that even I could sense after doing extensive research. I was confused and did not know what or who to believe. Most of the sources that I found on this topic were published by groups of females claiming that their gender is a major advantage and their vulnerability their main strength. They say themselves that they publish work that men could not create simply because of the unique emotional bound they share with their subjects and their extreme emotional abilities. But are those traits only womanly? Are male photographers not able to express the same emotional engagement and human connection? Women photojournalists indeed have access to the intimacy of houses in the Middle East. However, how is this different on an emotional perspective than Ashley Gilbertson’s ‘Bedrooms of the Fallen’ work?

There is a clear confusion that comes from many factors, some of them being that female photojournalists do not want to appear weak in a male-driven industry and therefore might not admit certain obstacles in fear of not getting the same opportunities as men, or even the fact that the American democratic system places a politically correct ceiling over every gender.

So this is what I propose:

I would like to create a forum that serves as a social media platform designed for photojournalists covering conflicts around the world. This forum, called Wars We Talk About will be decided in 2 major sections. First of all, there would be a public blog where anyone who signed up could post, comment, send messages, see profiles and send messages anonymously or not. This anonymous function is key as it might push both women and men to share honestly to the public, who would then hopefully get a more accurate understanding of the situation. Also, one can identify their gender if wanted when creating their own profile, they would be then put in relation with others who show similar profiles or interests, just like LinkedIn does for instance.

The second part of the website is the professional portal. Its access is restricted and you would need an ID and password to enter a the closed part of it. To get an ID code, the photographer’s info and credibility has to be verified first. This way, it would be easier to control and check the accuracy of the information shared.

Globally, throughout my research, I realized that even though there are some internal misunderstandings, the photojournalism industry’s principal strength is its community. This is especially relevant when looking at women photojournalists. I read many testimonies in which women explained how the support of other female photographers was extremely valuable to them. Therefore, I decided to add a supplementary sub-section in the Professional Portal through which professional female photojournalists can connect and communicate. But I also read a lot about how men are important actors in those women’s support system too. So, this professional part of the website would need to stay open to all genders. They could share, connect, ask questions, give advice…

The fact that those photojournalists have a very nomadic lifestyle can make communication challenging. Especially, I am thinking about safety and logistics. When working, women photojournalists mostly admit that they almost always need to be escorted by a male figure and that the team around them has a huge impact on the quality of their work. And, most of the time in war coverages, there is limited time so, building an efficient team locally might be challenging. Through that professional portal, I can imagine women giving other women advice on security, sharing contacts about drivers, bodyguards, etc… Men are also welcome to participate.

Through this social media platform, the key feature of war photography that I wanted to bring out and utilize positively was the strong sense of community that exists in that field. The public part of the platform would hopefully, through its anonymous possibility, shed a better light on the place of women in war photography, a matter that is still very blurry for a lot of people, including me. The professional aspect of it would be used as a functional tool in order to maybe facilitate some aspects of the very important logistical preparation involved when sending photographers to cover a conflict.

A beta draft of this online platform is available at: http://csm487.wix.com/warswetalkabout

Recent Comments