Photographic technology was first developed in the early 1800s, with the development of the camera obscura and photolithography methods. In 1927, French inventor Joseph Nicéphore Niépce took the first ever true photograph. Since then, amazing advances in the art and practice of photography have been made, from faster lenses, to smaller and lighter cameras, to the introduction of digital censors photo editing software, and more.

Photography was first developed as a way to capture the world in a snapshot. Only later did people begin to view it as an art form, as something that was created with an artistic, rather than documentary, mentality. Photographer Alfred Stieglitz was largely responsible for this shift in cultural thinking, with his early 1900s work. Since then, journalistic photography has continued on its similar path, maintaining its ethical devotion to truth in imagery, while art, or more artistic, photographic has bloomed in its own right.

These days, we live in a society plastered wall to wall with photographic imagery, and the vast majority of it seems to lean towards the fictional, artistic side. And often, it is not all that hard to tell if a photographic is a work of journalism or a work of art. Journalistic imagery is far less stylized and is almost always candid. On the other hand, artistic photography is usually far more contrived and created, and can be extremely stylish.

Holmes writes, “documentary photographers strive to be objective recorders of real events and don’t meddle with their pictures. And usually they are working on assignment…” (Holmes) Journalistic photography seeks to tell the truth, and represent it through pictures. In contrast, art photography tells fictional stories, with made up details, and characters that do not exist in the real world.

The one arena where it can be hard to see the line drawn between the real world and the fantasy art world is portrait photography, a practice used by both artistic and journalistic photographers. Portraiture is the only time that a journalist is ethically allowed to pose their subjects in the photo. Portraiture is also usually the only time that subjects of photojournalism acknowledge the camera—and they often look right into it.

But there are still rules for journalistic portraiture. As Knight asserts, “The subject isn’t usually doing anything, again because the viewer should not be confused as to whether the photo is a posed portrait or a real, documentary piece of journalism.” (Knight) Indeed, the New York Times “Guidelines on Our Integrity” states that “Pictures of news situations must not be posed. In the cases of…portraits…intervention should be unmistakable to the reader, and unmistakably free of intent to deceive.”

That is not to say that journalistic portraits cannot be artistic. Upon a glance over the body of work or either Magnum or VII, one would notice that all of these photographers, while depicting real, documentary images, do so in a way that is artful and pleasing to look at. This is apparent in all of the work of the tow agencies, but especially in the portraits.

One photojournalist that takes entirely truthful, yet highly stylized, portraits is Steve McCurry. My intent with this project was to explore this art/journalism distention by attempting to recreate the distinct style and emotion characteristic of his work. I felt that a visual format was most conducive for this examination, because of course photography is visual, so what better way to explore a another photographer’s style and intent that by doing my own photographic work? This way, I can put myself behind the lens, in the “driver’s seat” and force myself to make all the same choices that McCurry himself made. I felt that only through actually creating my visuals can I fully explore the distinction between the contexts, motives, and back stories of creating portrait photographs that are considered journalism or documentary photography, rather than fine art or commercial work. I wanted to explore this project because with much of my own work, I leave myself wondering into what camp my photos fall exactly. What makes a snapshot of someone art—even if the circumstances of the photo are completely natural and unposed—and what makes it documentary work. I felt that using McCurry’s work as a lens to explore this question was a great start to answering this question.

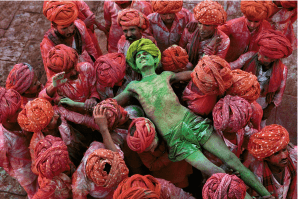

McCurry, who was born in 1950 and joined Magnum in 1985, has become legendary for, among other things, his portrait work. He is probably most known for his photo of a young Afghan girl with striking green eyes, which appeared on the cover of an issue of National Geographic. He is famed for photographing in India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Lebanon, and Cambodia. He is perhaps most noted for his portrait work.

After looking over a good portion of his work, specifically his portraits, I noticed some artistic trends. Purely stylistically, McCurry seems to always employ filmic, saturated (but not overly) colors, high contrast yet slightly crushed blacks, centered, chest-up framing, relatively shallow depth of field, and moody use of shadows. As far as the content of the frame, he tends to shoot in the field, against often very character-building (for the subjects of the photos) background, and is able to expertly capture emotion. This is partly due to his focus on the subjects’ eyes. Always looking into the lens, the subjects have eyes that true to the saying, allow a peak into their souls, and consequently make the photo overwhelming compelling.

I was highly inspired by these photos, so I decided to make my own. My photographic exploration can be viewed at my site: http://bencsearles.weebly.com/ , which shows a project that I called “ATTEMPTING TO CAPTURE THE ‘HUMAN CONDITION’ THROUGH PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY IN THE SPIRIT OF STEVE MCCURRY.” All photos were taken in what I considered a journalistic, rather than strictly artistic, context. The first shot, a portrait of the homeless street artist Lex posing in front of his work, I took while assisting my friend Erin shoot a short documentary focusing on Lex’s life and work. Because we were interacting with Lex as journalists and documentary filmmakers, this photo serves less as a piece of fine art, which happens to include the photographic representation of a human, and more of a factual documentation of the contents of the frame. This is how Lex looks, and this is him posing in front of the his art, on the street where he sells it almost every single day.

I feel that I was able to mostly successfully capture the McCurry portrait spirit with this shot. Lex is center framed, shown-chest up, and placed in front of a blurry, character-building backdrop. He is staring deeply into the lens, and has a somewhat pained, yet very complex look on his face, especially apparent in his eyes. The photo is colorful, but not too highly saturated, and the colors are filmic and defined with a fair mount of contrast.

My though process behind the rest of the photos is similar. Every photo is framed similarly, and every subject is framed in front of a background that I feel works to contribute to the subject’s character. More importantly, these are all photos that while they are (hopefully) aesthetically pleasing, were taken in a journalistic context, as a way to document, rather than eventually entertain. For the last three photos, I broke away from the standard McCurry portrait framing, to take photos that I felt leaned slightly more towards my own style.

Recent Comments