VII is reinvention. What I see on the loading page of the VII website are images that are bright, energetic, but most of all, driven by political themes in the modern world. Searching through the years of work of their photographers, it’s no secret that VII is a physical embodiment of the major political and social events of the 21st century. I did not see images that were conventional and felt as if each photographer and project was pushing new ground, aided by the fact that many of the images are digital, after all, it was meant to compete with Getty and Corbis. Out of some of the least conventional photojournalism I have seen to date, two photographers that stood out and encapsulated the impression that VII left upon me were Alexandra Boulat and Maika Elan.

Maika Elan is a vietnamese photographer who was a sociology student at the University of Hanoi until she took up photography and, at a rapid pace, ascended to a professional level. In 2010 she started documentary photography after spending years as a fashion photographer and by 2013 was a member of the VII Mentor Program. A large amount of her work for VII is from Malaysia and Vietnam, documenting rituals, LGBT couples, family, and friends.

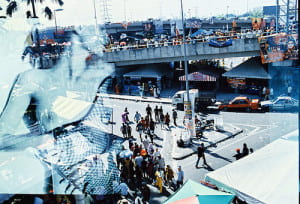

Upon first glance of Elan’s photographs, I was surprised when I saw double-exposed images. I have never seen any photojournalistic project that has utilized this technique, it largely remains confined to more aesthetic and concept-based photography. Her project Here Comes Thaipusam was one that left a lasting impression on my visual senses. In this project, Elan documents the Thaipusam ritual in Kuala Lampur, a ritual that dates back centuries. Before going on assignment, Elan exposed her film to frames of a Western fashion magazine she was reading. As a result, each of the images of this long standing ritual are contrasted with images of the magazine, providing a juxtaposition of tradition and religion to sex and product driven advertising. In one image, she superimposes a high-fashion model woman with one breast exposed onto an image of a large crowd of Thaipusam celebrants on their way to Batu Cave, the starting place of the religious ceremony. The colors are muted, and the dominant hue is blue, causing the viewer to feel colder, which accentuates the distance between the two images now morphed into one. The contrast between the two photos is heavy handed, mostly because we are aware of the fact that Thaipusam is a religious and traditional festival and feel out of place staring at an advertisement that as a citizen of the Western world, we see almost every day. It begs the question, has the Western world’s ritual become shopping or worship of products? In a second image, she contrasts an image of Malaysian men praying and marching in the ritual to another high-fashion image of a woman modeling what seems to be an expensive pair of shoes and yellow pants. There is a large juxtaposition in this image of color, the yellow pants of a high-fashion female model matching with the yellow accents of the dress of the men in the ritual. In these two entirely different worlds, the form, shape, and stance of people remains the same. It invokes a sense of universality, maybe we cannot relate entirely to the religious or spiritual ritual, but we certainly can draw a physical comparison and maybe that is a start to understanding cultures and places entirely foreign to our own.

Alexandra Boulat, one of the founding members of VII, was originally from Paris and first studied art history and graphic art at the École des Beaux-Arts before starting photographing, represented originally by her mother’s agency, Cosmos, and Sipa press for a decade. In 2001 she founded VII along with several peers and spent most of her photographic career focused on warzones in former Yugoslavia, Iraq, Israel, and Palestine, although her work does not stop at war-related images and includes a wealth of social and economic issues of the late 20th, and early 21st century. She is one of the most renowned photojournalists in modern times and has received a myriad of the highest prestige of awards for photography including the ICP Infinity Award, Eisenstat Award, and the Perpignan, Visa d’Or pour I’Image.

Alexandra Boulat’s photographs utilize heightened realism to it’s fullest potential, keeping her images often times brutally realistic and either jarringly still or blurred while in motion. I was drawn to her first project in Gaza, which contains an image of a man being pushed on an ambulance stretcher through what appears to be a hospital. The photograph is blurred from the forward pushing motion of the emergency responder. There are only two visible faces, the urgent expression of the EMT, and the shocked and concerned face of an onlooker staring at the injured man. The photo carries an immense amount of weight with it, we see several cameras around this man and the EMT struggling to push through. Despite the intensity of the situation, there remains a savior, committed to keeping this man alive. The viewer sees the power of the human will in one fleeting moment, we feel propelled by the pure raw energy of the man pushing the injured man to safety. In a second image, three men are gathered near a young child in a hospital bed. One man, who may be the father of the young child, looks at the camera with great concern, the child, still innocent, also looks at the camera. Off to the right, two other men have bowed their heads in prayer. The image of a child in a hospital bed with a cast on his leg draws strong emotion, as many photo’s of children tend to do. However, Boulat is saying more than just about who gets hurt in war, she is also exploring the purpose of prayer and religion. These men may have almost seen this young child die, and for that reason they remain somber, in prayer, perhaps hoping their situation will change. The image asks the viewer to look beyond just the physical manifestations of war, but also the social and mental ramifications as well. As long as bombs continue to be dropped, people will continue to pray, a hopeless gesture, but one that is all one can do in a violently hopeless scenario.

– Tristan Oliveira

A group of men walking and praying on their way to Batu Cave in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia on Feb. 1 2012, is overlaid by images of fashion models from a beauty magazine. Thaipusam is known as a very enigmatic festival, mysterious and frenzied. In the words of Maika Elan, “Thaipusam looked like a pilgrimage of a bygone era.” As an avid reader of magazines, Elan wondered how photographs of the traditional culture and people of Thaipusam would look exposed in contrast to media images of modern popular culture. As an experiment, before first visiting Batu Caves in Malaysia where the festival took place, she exposed a few rolls of film with images from the magazines she read. At the Thaipusam Festival, the film was re-exposed over the initial fashion magazine images.

Prayer time at the Al-Shifa Hospital on the bloodiest day of the Israeli incursion (21 were killed and more than 50 injured) in the northern Gaza Strip, Palestine, July 6, 2006. The Israeli military operation, dubbed “Summer Rain,” is aimed at winning the freedom of a captured Israeli soldier and lifting the threat of near-daily Palestinian rocket-fire on southern Israel.

An injured Palestinian from the Hajjaj family arrives at the Al-Shifa Hospital in Gaza City, Palestine, July 8, 2006. Three members of the family were killed, including a six-year-old girl, in an attack on their home in Karni, east of Gaza City in the Palestinian territories. The Israeli military operation, dubbed “Summer Rain,” is aimed at winning the freedom of a captured Israeli soldier and lifting the threat of near-daily Palestinian rocket-fire on southern Israel.

People gather outside of Batu Cave where the Thaipusam festival is held in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia on Feb. 1, 2012, and is overlaid by an image of a fashion model from a beauty magazine. Thaipusam is known as a very enigmatic festival, mysterious and frenzied. In the words of Maika Elan, “Thaipusam looked like a pilgrimage of a bygone era.” As an avid reader of magazines, Elan wondered how photographs of the traditional culture and people of Thaipusam would look exposed in contrast to media images of modern popular culture. As an experiment, before first visiting Batu Caves in Malaysia where the festival took place, she exposed a few rolls of film with images from the magazines she read. At the Thaipusam Festival, the film was re-exposed over the initial fashion magazine images.

Dear Tristan,

Nice job overall. I particularly like when you develop the visual reading through an interpretative lens as you do so nicely here: “The image of a child in a hospital bed with a cast on his leg draws strong emotion, as many photo’s of children tend to do. However, Boulat is saying more than just about who gets hurt in war, she is also exploring the purpose of prayer and religion. These men may have almost seen this young child die, and for that reason they remain somber, in prayer, perhaps hoping their situation will change. The image asks the viewer to look beyond just the physical manifestations of war, but also the social and mental ramifications as well.” As regards that same image, what do you make of the fact that the boy and one man stare directly into the camera? How does this affect the image, and our reaction/s to it?