Last summer, I stumbled across a job opportunity to work for a startup website nestled within the IT department of a new real-estate investment and development company named HAP, located in Midtown. Having been unfamiliar with real estate and just about anything corporate, I was not fully affiliated nor understood the company until I was commissioned to produce promotional images and video by proximity that my office for the website was within theirs. I was asked to visit various construction sites and cut together short updates regarding how far along the building processes were for each, accompanied by the site supervisor. I created somewhere around 8 videos over the course of a few months, and finally I noticed a pattern. Out of all ten of the projects currently being developed by HAP, excluding the new HAP Tower in Jersey City, six were located in East Harlem, relatively close to the subway in residential areas largely lower-middle and middle class. I had been reading about gentrification in Harlem since the start of college, and I had not realized that I was seeing an intermediary process of displacement and gentrification right in front of me, even if it was far along for many years. Through the classes I took, including one in which I produced a website about Harlem and it’s history/democratic shifts and another in which I produced a small documentary interviewing long time residents of Williamsburg and seeing their perspective on their rapidly changing neighborhood. Through these experiences, I had grown to oppose gentrification, yet only a few months prior I was documenting and helping facilitate the very process.

For many reasons, including the defunding of the website startup, I left HAP, well aware of the precautions legally to me sharing the work I produced for them. I never received any compensation for my work and had to sign release forms stating that HAP was the only entity allowed to publish the content I had made for them, so as many of my college-age New York colleagues would understand, I got, for lack of a better word, “interned.” Yet I was hungry to learn more, I felt my morals had been compromised. What I discovered all this time later is how cryptic, bureaucratic, and nuanced gentrification is as a process and how difficult it is to pinpoint exactly where to affect positive change within neighborhoods experiencing it. After all, I am a student at a university responsible for helping gentrify and monopolize entire sectors of lower Manhattan, including the East Village regarding the demolition of St. Ann’s Church despite numerous community protests against the action. I am already contributing through my tuition.

Gentrification has become a major subject of discontent and discussion within the past 25 years, especially in New York City, where neighborhoods like the East Village and Wiliamsburg, once home to lower income housing, have now become some of the most expensive places to live in the world. Ask many born-and-raised New Yorkers and they will tell you that it is the worst thing ever to have happened to the city. The concept of gentrification is rather simple, investment companies purchase plots of land inexpensively within neighborhoods that at the time are lower income. Once the surrounding areas become more populated and there becomes a demand for wealthier people to find housing, they move into the lower income neighborhoods that have essentially have been paved for them, forcing the original residents of the neighborhood out and displacing thousands of people. Take Harlem as a case study, a neighborhood rich in diversity and home to a large African-American population. From 2000-2005, 32,500 African-Americans were displaced from Harlem and were replaced by approximately 22,800 white residents, and the number has been growing ever since. With real estate becoming more and more upper-class in New York City, developers and investment companies are setting their sights on other neighborhoods, the next in line is El Barrio, or East Harlem, one of the most diverse places in New York and a historical home to a true melting pot of cultures and ethnicities including Puerto Rican, African American, Mexican, Italian, and Dominican. East Harlem

Gentrification is a self-aware process, we want to know where to point fingers, but who exactly is to blame? We can criticize the residents of the buildings themselves, but did every resident collectively organize this effort? No, but there is something to be said about how it’s usually rich, whiter people who gentrify neighborhoods, especially in New York City. But why? Well, because they are the only people who can afford the rising costs, as in Harlem, where the typical price for an apartment is over $458 per square foot. This is bound to happen when years prior real estate developers and investment platforms purchase the same properties, waiting for the opportune moment to turn it into an apartment complex, or sell it to Whole Foods. Take Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn, where the median sales price for a home jumped from $455,000 in the second quarter of 2013 to $621,000 in 2014. This is largely due in part by organizations like CityShares, multi-million dollar investment platforms that are “seeking to capitalize on the neighborhood’s sharp growth” by buying up large sums of land and constructing them into whatever turns profit best, and a city already as overpopulated as New York, housing is an ever growing demand.

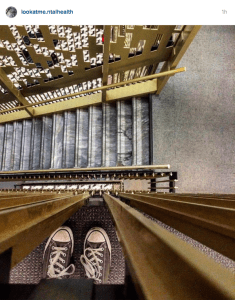

For this project, I decided to revisit the construction sites in East Harlem that HAP is currently developing and photograph them, hoping that documenting the current process and surrounding neighborhoods can provide a means for an audience to see what is going on and hopefully feel inspired to do something about it. I took inspiration from several Magnum and VII photographers with projects and works in New York City, including Elliott Erwitt, Bruce Gilden, Richard Kalvar, and Ron Haviv. I did not set out to pull a certain style from each photographer as much as try and attempt to capture images of a subject that is aesthetically uninteresting in hopes to inspire. Thinking especially of Haviv’s, I tried to play with a tone of complacency, hoping to turn what seems like a mundane occurrence in New York or any major city into something informative, hoping they might ignite action.

Ultimately, HAP is not a major development company, and have plenty of legal issues they are currently fighting in regards to their projects. They are not the face of gentrification nor are they leading it, but it is the myriad of groups like them that are helping force lower income residents out of their neighborhoods. To actually make a difference, it requires action, and solidarity with local efforts, such as the East Harlem Preservation and GOLES in the Lower East Side. Supporting local businesses also is has a large impact, as many businesses lose grounds to larger corporations and chains as neighborhoods drastically shift. Gentrification is not a natural process, it ruins communities and forces people out of their homes, and to help hinder such an elusive process, the support of local efforts comes first and foremost.

Recent Comments