instagram.com/lookatme.ntalhealth

The medium of photography has the capacity to be extremely personal and entirely honest. Unfortunately, the medium is also able to be dishonest; images hold more power than we consciously assume, and they can easily perpetuate stereotypes and stigmas within our society without complete intent. With regards to mental illness, a powerful stigma exists in all aspects of our society. As Peter Byrne points out in Advances in Psychiatric Treatment in 2000, “Mental illness, despite centuries of learning and the ‘Decade of the Brain,’ is still perceived as an indulgence, a sign of weakness” (Byrne 1). There are many complex reasons as to why this stigma still exists today, regardless of the advanced knowledge the science world now knows about mental illness. Photography plays an arguably significant role in the preservation and extension of this stigma; more often than not, photos of extreme, isolating images are used to represent the whole of mental illnesses in the media, advertising, and even so-called awareness campaigns. This stereotypical, false representation of mental illness is not only unfair, but also truly detrimental towards any attempts to break down the social stigma surrounding the mental health community.

Photography and mental illness come together in a large, positive way in the work of Ashley Gilbertson. He is of course renowned for his work with preserving the memory of veterans, many of whom died due to poorly diagnosed or poorly treated mental illnesses after returning home from war. Gilbertson himself openly speaks about his personal encounter with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) after he returned from covering the war in Iraq (Mccauley). His ability to identify with this mental illness undoubtedly heightens his ability to photograph it truthfully.

In 2013, Gilbertson photographed Stacy Pearsall, a fellow conflict photographer who was in the midst of coping with PTSD and suicidal thoughts after having travelled imbed in Iraq and Afghanistan. The photos are stunning; they show Pearsall smoking a pipe in the woods behind her house and tending to her horse outside her barn. They are very high quality images, but the content is overwhelmingly average. Pearsall does not look incredibly sad, nor incredibly happy. She simply exists in her personal normalcy. Herein lies the beauty of these photos: Gilbertson was able to capture a woman with a mental illness just acting like a human being.

This series of photos was the inspiration for my project. I have personally dealt with mental illness in family members around me growing up, and within myself. I also feel personally affected by the stigma – I ignored the social anxiety and depression that shaped my life for as long as possible. I unknowingly partook in “self-stigmatization,” which is accepting a stigma to be true and then turning it on oneself, usually in the form of shame (Corrigan 485). On this topic, Byrne again ponders:

The question arises as to just what all this shame and secrecy is about. Negative cultural sanction and myths combine to ensure scapegoating in the wider community. The reality of discriminatory practices supplies a very real incentive to keep mental health problems a secret. Patients who pursue the secrecy strategy and withdraw have a more insular support network.

All of the stigmatizing in our society is supported in the photographs and portrayals we see representing mental illness. In a study of how mental illness is shown in television, a study found only 3% of characters to be openly impacted by an illness, and of that small percentage, “the mentally ill were most likely to commit violence and to be victimized (Signorielli). Additionally, “the mentally ill characters were less likely to be employed outside the home, and if so employed were likely to be seen as failures” (Signorielli). In advertisements that deal in some way with mental illness – whether it be for medication to treat symptoms, a suicide hotline promotion, or just a general good-will ad about reaching out to those in need – the illness is always portrayed in the extreme. A dark, depressed man curled up in the fetal position, meaning depression. A woman with her face in her hands, hair frazzled, meaning anxiety. These images are difficult to relate to for someone without these illnesses, and they may even be difficult to relate to for someone with these illnesses – photographs that dramatize and even exaggerate certain characteristics of mental illness further the distance between “the mentally healthy” and “the mentally ill,” prolong the tendency to “other” those who suffer from an illness beyond their control, extend the cycle of shame and fear and secrecy, and perpetuate the stigma surrounding mental illness.

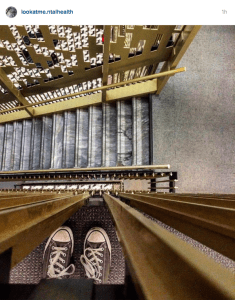

With both this and the refreshingly more pleasant and “normal” work done by Ashley Gilbertson in mind, my project became an attempt to capture, basically, a boring day in the life of someone with social anxiety. I based the style of my photography on Jessica Dimmock’s series of photos on uninsured Americans – she used low-resolution, almost grainy imagery to show a woman’s struggle to receive cancer treatment without health insurance. I loved the way the images looked, and as I was only working with the camera on an iPhone 5S, the idea of “low-res” was particularly appealing.

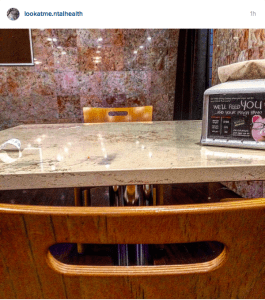

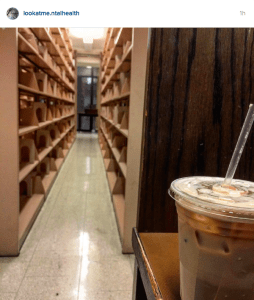

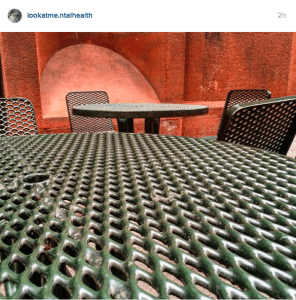

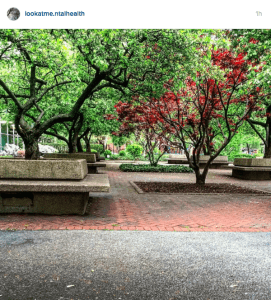

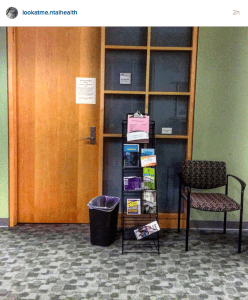

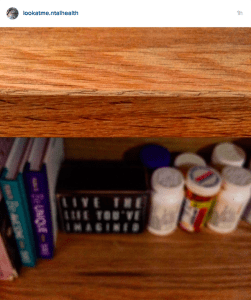

None of my photos have people in them, and that was a conscious decision. Thinking through the biggest day-to-day struggle for me and my anxiety, I felt that finding a place to sit is always the most challenging. Having spoken to other people with similar anxieties, this seems to be common – it can be very stressful to either sit surrounded by other people or sit alone; nothing ever feels ideal. So, the majority of my images deal with seating in some capacity. One shows the outside of a therapist’s office, which is just a regular office in the Liberal Studies building; one shows medicine mixed in on a bookshelf. I created an Instagram account for this project and uploaded my photos through there, mimicking Dimmock’s style through filtering each photo in the same way. I felt a social media account would be ideal to present these bland, fairly boring photos – through social media, we are expected to present our best, most idealized self to the world. This only adds to the capacity and tendency to be secretive and ashamed of one’s true feelings and struggles.

I know I am not a good photographer and I certainly do not claim to be one. I had a strong motivation and idea behind my project, and I carried out the visual side as best I could. What I hope is conveyed through this project, even a little bit, is that “normal” means so many different things to so many different people. Someone with a mental illness has a different “normal” than someone without one, but that does not make them any less of a person. Portrayals of mental illness in photography and the media only make this more difficult for people to see; the stigma surrounding mental illness will not break down until people are able to see one another not as “other,” but as fellow human beings.

Works Cited

Byrne, Peter. “Stigma of Mental Illness and Ways of Diminishing It.” BJPsych Advances, 06 Jan. 2000. Web. 06 May 2016.

Corrigan, Patrick. “Structural Levels of Mental Illness Stigma and Discrimination.” Schizophrenia Bulletin. Oxford Journals, n.d. Web. 04 May 2016.

Dimmock, Jessica. “America’s Uninsured.” VII Photo Archive. VII Photo, 2007. Web. 02 May 2016.

Gilbertson, Ashley. “Military Suicide.” VII Photo Archive. VII Photo, 2014. Web. 03 May 2016.

McCauley, Adam. “Overexposed: A Photographer’s War With PTSD.” The Atlantic. Atlantic Media Company, 20 Dec. 2012. Web. 06 May 2016.

Signorielli, Nancy. “The Stigma of Mental Illness on Television.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 33.3 (2009): n. pag. Taylor & Francis Online. Web. 03 May 2016.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.