A program entitled “Orphans Films of Outer Space,” is part of the World of Knowledge International Film Festival of Popular Science and Educational Films, which runs December 1-6, in St. Petersburg, Russia. On Sunday, December 5, 2021, I will introduce the films (via Zoom, alas) to the viewers in the New Holland Pavilion. After the terrestrial projection of a 16mm print and four digital videos, filmmaker Jeanne Liotta and I will participate in a Q&A.

The Comet (Edison, 1910) 2′ with the premiere of a new soundtrack composed Andrew Goehring (NYU Screen Scoring program)

Meteorites (Pavel Klushantsev, 1947) 10′

Beyond the Moon (R. E. Barnes, ca. 1961) 11′

Project Apollo (Ed Emshwiller, USIA, 1968) 30′

+ a non-orphan film, Observando el Cielo (Jeanne Liotta, 2007) 19′

The festival notes its theme this year is space, observing the 60th anniversary of Yuri Gargarin’s flight, the first into space by a human being. In February of this year, Walter Forsberg and I did a similar event for the space exploration conference known as Roger That! Here’s a link to the launch of a series of blog posts about ten films that appeared on the DVD set Orphans in Space: Forgotten Films from the Final Frontier. That project included two productions from the Soviet Union, so a Russian festival on popular science films is a fitting next step.

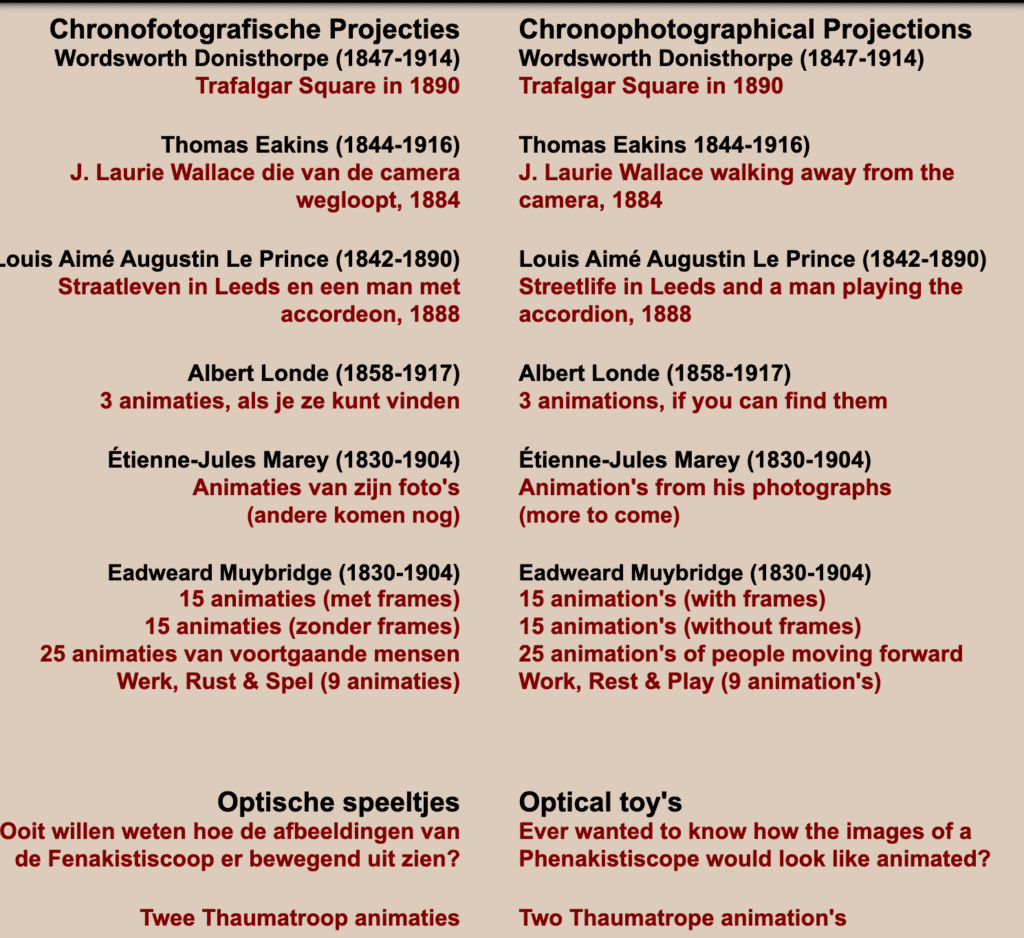

I will publish full program notes here soon, but first here’s an illustrated program of pre-cinema and early cinema artifacts on the theme that others have published online. Total running time: 80 seconds.

Program notes by Dan Streible

Passage de Vénus (Jules Janssen and Francisco Antônio de Almeida, 1874) 5 seconds.

This 2012 YouTube post by “magical media museum” is the oldest one on the web in 2021. Where did it originate?

A noted French astronomer and Brazilian engineer invented a photographic gun to record a set of images of the planet Venus passing before the Sun, as seen from Japan, December 9, 1874. But this video reanimation of the daguerreotypes made using Janssen’s “revolver photographique” is not what if first seems. In fact, these animations found on several YouTube channels do not say where they came from. Who made them when and how? This 2012 posting by the Media Magic Museum channel is the oldest YouTube post, but certainly not the source of creation.

A book on Janssen, by Françoise Launay of l’Observatoire de Paris, cites one Charl Lucassen posting a video of the 1874 images to his personal website in 2004, now defunct. (For the record, web.inter.n1.net/users/anima/chronophl janssen/index.htm is the URL cited. A search for Charl Lucassen indeed finds others citing his “amazing” website of chronophotography animations. A redirect to web.inter.nl.net/hcc/anima/chronoph/motion/index.htm allows the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine to document this URL operated from 1998 to 2004. None of the screenshots located any Janssen images, but one can see an index of Lucassen’s once media-rich site. This screenshot is dated October 18, 1999. Only the text survives.

Elsewhere, another Launay footnote tell us where the reanimation was born. In 1950, Joseph Leclerc, founder of the film archive of Société astronomique de France, rephotographed the tiny images on one of Janssen’s discs using a motion-picture film camera. Leclerc wrote about it in “Jules Janssen et le cinématographe,” l’Astronomie, 69 (1955): 388–91.

The punchline is that Launay established in 2005 that the images we see reanimated are from a “practice plate” Janssen made when photographing simulations of the transit of Venus before the celestial event. In 1950, Leclerc mistakenly believed these were from the “revolver photographique” daguerreotype disc that Janssen and engineer Francisco Almeida made in Japan. Janssen did successfully make the 1874 photographs, but they do not survive.

The Transit of Venus (David Peck Todd, 1882) 15 seconds.

An American astronomer made 141 glass-plate photographs of the phenomenon as seen from California. The plates were rediscovered at the Lick Observatory and reanimated in 2003 by William Sheehan and Anthony Misch. The 15 seconds of video represents more than 4 hours of the complete transit. Here is a 2012 copy from Sze-leung Cheung.

See Sheehan and Misch, “A Movie of the 1882 Transit of Venus Assembled from Plates Taken at Lick Observatory by David P. Todd,” Journal of Astronomical Data (Nov. 2004) and”A Remarkable Series of Plates of the 1882 Transit of Venus,” (Dec. 2004).

Solar Eclipse (Nevil Maskelyne, 1900) 375 frames of 35mm film shot, 1 min.

On May 28, 1900, a British amateur filmmaker recorded a total eclipse of the sun in North Carolina (U.S.) using a custom-rigged motion-picture camera. Rediscovered in the Royal Astronomical Society archive and restored in 4K by the BFI National Archive in 2019.

As a cinematic experience, this little film of a big thing still has oomph, even in this 720p video stream. The 4K file is available to license from the BFI.

Two lost films:

[Eclipse viewed from Viziadrug, India](Lord Graham, 1898) Eclipse Expedition, Royal Astronomical Association.

[Eclipse viewed from Buxar, India] (Gertrude Bacon, 1898) Eclipse Committee, British Astronomical Association

Three 35mm cameras in India shot the January 22, 1898 solar eclipse. A large professional scientific team from the Royal Astronomical Association, led by Norman Lockyer, took a battery of cameras and instruments, including the motion picture gear. In the book Recent and Coming Eclipses (1900) he refers to two “kinematograph” machines, one to film the eclipse, the other its shadow. Each with its own crew. Lockyer reported that 8,000 frames were exposed, however a crack in the wooden camera box allowed too much light in, fogging the images beyond any use. The operator he identified as the Marquis of Graham.

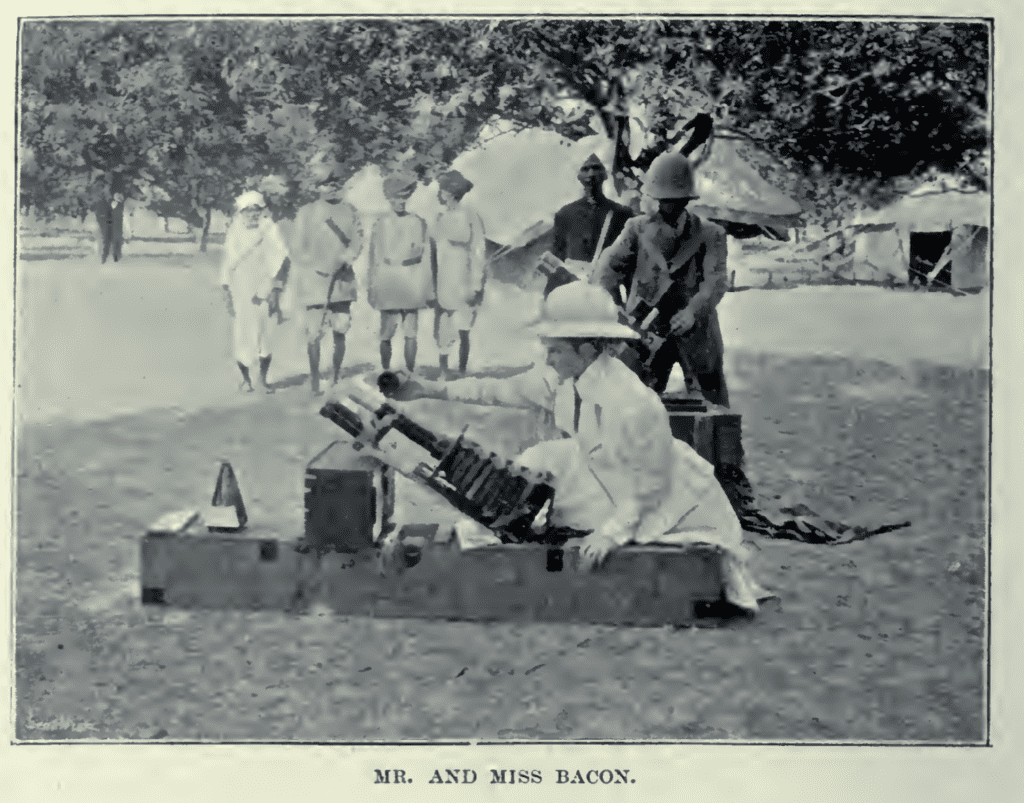

Meanwhile, for the amateurs in the British Astronomical Association, Gertrude Bacon, her brother Fred, and father John M. Bacon reported their film of the eclipse was successfully recorded using an “animatograph.” Some sources mistakenly say the noted magician Nevil Maskelyne was the cinematographer, but he was not present. However, it was Maskelyne’s camera and film stock the Bacons used. The name Animatograph specifies the invention of Robert W. Paul, who indeed worked with Maskelyne and purchased the rights to his adaptations of the camera.

The expedition’s published report said: “The heaviest and most important instrument was undoubtedly the animatograph telescope, specially designed for the expedition by Mr. Nevil Maskelyne. As a piece of delicate and complex mechanism this apparatus demanded much care and manipulation, and a certain period of each day was set apart for requisite practice. At intervals, too, during the voyage, a practical use was made of its capabilities. A number of spare films had been supplied by Mr. Maskelyne, in addition to one of special length for the eclipse; and with the consent and ready co-operation of our genial captain several photographs of animated scenes on board ship were secured.” (33).

Newspapers noted the presence of the special cameras in Buxar and sometimes reported they had captured the solar eclipse on films, with their owner Maskelyne about to show them publicly in London at his popular Egyptian Hall. (Edinburg Review, April 1899, 316)

However, when the ship carrying the Bacons’ films and Maskelyne’s camera arrived in England, all arrived safely — but for the can containing the eclipse footage. In public talks about the India expedition, John M. Bacon showed photographs taken by Gertrude and Fred, but told of the disappointment finding the eclipse film had been lost or stolen.

Sources:

E. Walter Maunder, ed. The Indian eclipse, 1898: Report of the Expeditions Organized by the British Astronomical Association to Observe the Total Solar Eclipse of 1898 January 22. (1899).

Sir Norman Lockyer, “Total Eclipse of the Sun, January 22, 1898, Preliminary Account,” Report on the Solar Eclipse Expedition to Viziadrug (1899).