Original music composed and recorded by Agatha Kasprzyk and Rafaël Leloup, 2012. Commissioned for the DVD set Orphans in Space: Forgotten Films from the Final Frontier. (See the 2021 site updating research on these films.)

A Trip to the Planets (192?) 17 min., b&w/color, tinted, silent.

Narration by Megan Prelinger, 2012

Soundtrack by Agatha Kasprzyk and Rafaël Leloup, 2012

Source: Prelinger Archives, Library of Congress

As cultural historian Megan Prelinger notes in her voice-over commentary, A Trip to the Planets is “a true orphan.” Production credits are absent from the 16mm print, perhaps deleted by a producer-distributor of second-hand goods to cover its tracks. Perhaps simply lost, as with so many heads and tails of older films. Even this title was created after the fact, as we find no record of a silent-era film with this title. Nor any non-English titles that might translate as “a trip to the planets.” However, a few days after the Orphans in Space DVD began circulating in 2012, a pseudonymous writer (gun_shy) left the first comment on the Internet Archive’s posting of the Prelinger Archives video: “The correct name of this film is …. Wunder der Schöpfung (Germany, 1925), with the English-language version called Our Heavenly Bodies.” This is mostly correct. But the full answer is more complicated – and illustrates how some films become orphans.

How did this short film derived (mostly but not entirely) from a high-end, feature-length German Kulturfilm transmute into the form that survives?

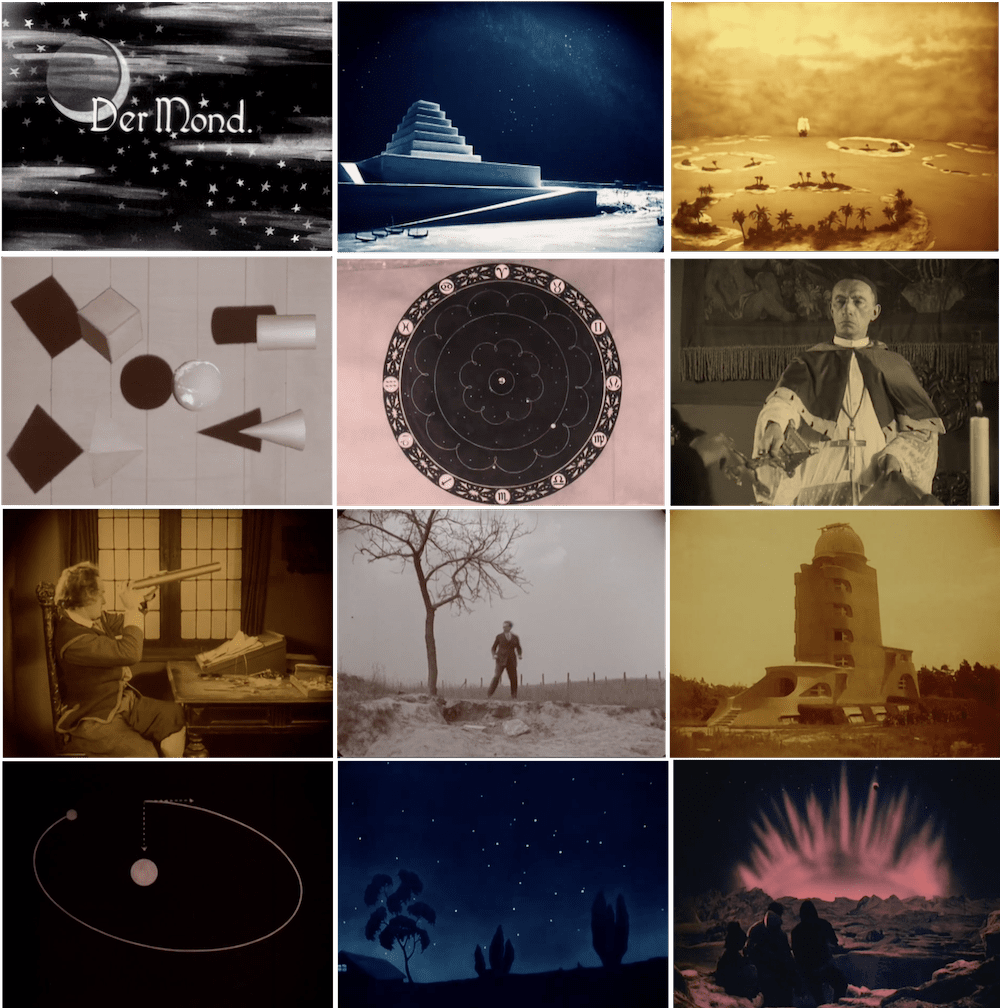

The Munich Film Museum restored the feature-length German Kulturfilm Wunder der Schöpfung in 2008, issuing a DVD edition with German intertitles and an English voice-over translation (no subtitles). Nearly three years in the making, the 1925 educational film had an exceptionally large budget and a crew of dozens of technical experts, designers, writers, unit directors, and cinematographers. Director writer Hanns Walter Kornblum was its guiding force. In its aesthetic achievement, his film compared favorably with the best-known silent movie from Germany, science fiction epic Metropolis (1927), which it outperformed at the box office. The DVD booklet essays by Stefän Drössler, Ronny Loewy, and Stewart Tryster offer rich historical background about the movie. (The Wikipedia entry on Our Heavenly Bodies is helpful too, containing an outline of the seven acts/reels.)

In the restored Wunder der Schöpfung, the array of color tinting and toning demonstrates unusually lavish production values for an educational film. A Trip to the Planets limited its 16mm print to a single tint.

However, the puzzling film bearing the title card A Trip to the Planets is itself a unique work, not simply a short version of Wunder der Schöpfung. The Prelinger Archives print may be the only surviving copy. Most of the images are indeed from the German source, but some come from unidentified fragments. In this sense it is a compilation film, one containing a conspicuous number of intertitles. As many as a dozen consecutive texts roll by with no intervening images – a sign of a cheap and hasty byproduct. Another indication that A Trip to the Planets is not simply a condensation is the hodgepodge of fonts and designs among these intertitles. It has an opening title (or is that an intertitle from Heavenly Bodies?) and a “The End” final shot suggesting it is (and was intended to be) a whole work, however derivative or bootleg. But who made it? when? who saw it?

Wunder der Schöpfung was widely seen in Germany as a seven-reel feature, but there is little evidence of its distribution abroad in that form, particularly in the United States. The dominant German film distributor UFA had U.S. offices and a contractual partnership with Hollywood, particularly with Paramount and MGM after the so-called ParUfaMet agreement of 1925. I can find no evidence that the full-length Wunder der Schöpfung received American theatrical screenings. No listing either for the English title Our Heavenly Bodies, which the 2009 DVD uses. Instead, in 1927, MGM released a silent one-reel version as an “Ufa Oddity” under the title Heavenly Bodies, one of 80 shorts rolled out during 1926-28. Thereafter, the short version had documented nontheatrical distribution, with rentals or sales to schools, churches, and others. It had a long life in that sphere, remaining in American 16mm rental catalogs until at least 1945.

Most publications that use the title Our Heavenly Bodies take it from the 2009 DVD; only a handful of sources used it in the late twentieth century and only one that I find before 1972. “Movie Shows Wonders of the Universe,” Science and Invention, July 1927, refers to the “seven long reels” of Our Heavenly Bodies. A few latter-day science and film history books mention Kornblum’s production under other English titles: Wonders of Creation, Miracles of Creation, In the World of the Stars, and In the World of the Planets and Stars. A print catalogued as Heavenly Bodies (1920s) survives in the Prelinger collection, a 10-minute fragment from Wunder der Schöpfung. Its opening title card reads “HEAVENLY BODIES. Gravitation. The Moon. Constellations.” The reel ends abruptly mid-action. Searching for accounts of a film called Our Heavenly Bodies was indeed a red herring. Omitting the Our leads to many primary sources confirming the German film circulated in the United States from 1926 onward, but as a one-reel release.

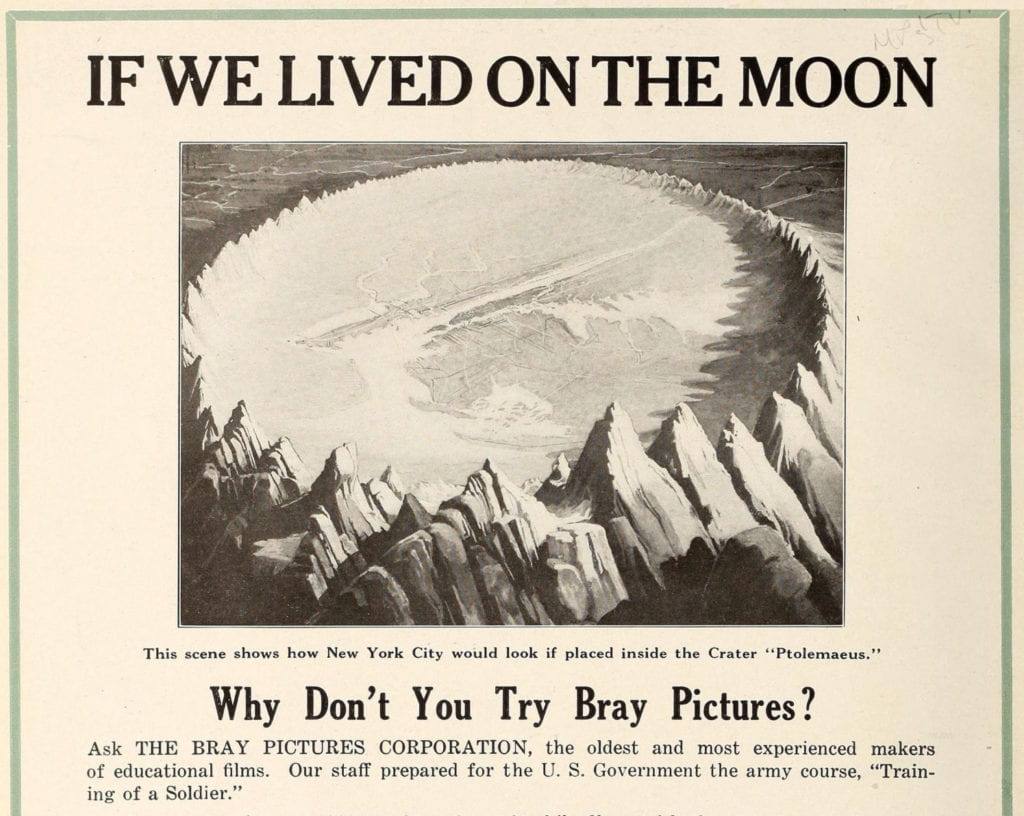

Initially seeking to identify footage sources for A Trip to the Planets, press descriptions and published stills led me to suspect some shots might be from Max Fleischer’s animated 1920 short All Aboard for the Moon (aka All Aboard for a Trip to the Moon), part of Goldwyn-Bray Pictograph no. 424. As animation historian Ray Pointer notes, Fleischer supervised other Bray Pictographs about the solar system at this time: Eclipse of the Sun (1918), The Birth of the Earth (1919), Hello, Mars (1920), and If We Lived on the Moon (1920). Bray Pictographs ran in movie houses and then circulated in nontheatrical settings, especially American classrooms. Although it was only a segment of a one-reel release, a leading trade magazine noted it as simply “one of the best bits of educational film ever made.” (Wid’s Daily, Feb. 22, 1920).

Entry into the new classroom market is evidenced by an illustrated profile of Fleischer, the Bray studio, and All Aboard for the Moon in Educational Film Magazine (Feb. 1920). Pictograph educational subject matter covered categories such as “science, biography, invention, biology and civics,” according to an ad in the magazine. In the United States, the visual education movement blossomed in 1920, with teachers and administrators advocating for motion pictures in nearly every branch of learning. Companies large and small were formed to sell to this new market. And the commercial studios repurposed theatrical films to secondary, nontheatrical outlets.

Searches for All Aboard for the Moon bore little fruit until realizing that Bray released it solo as If We Lived on the Moon. Two fragments viewable online differ considerably in content and quality. On the left, Fleischer studios YouTube post; right, audiovisual metaphors. Sound removed.

[archiveorg if-we-lived-on-the-moon-x-2 width=640 height=480 frameborder=0 webkitallowfullscreen=true mozallowfullscreen=true]

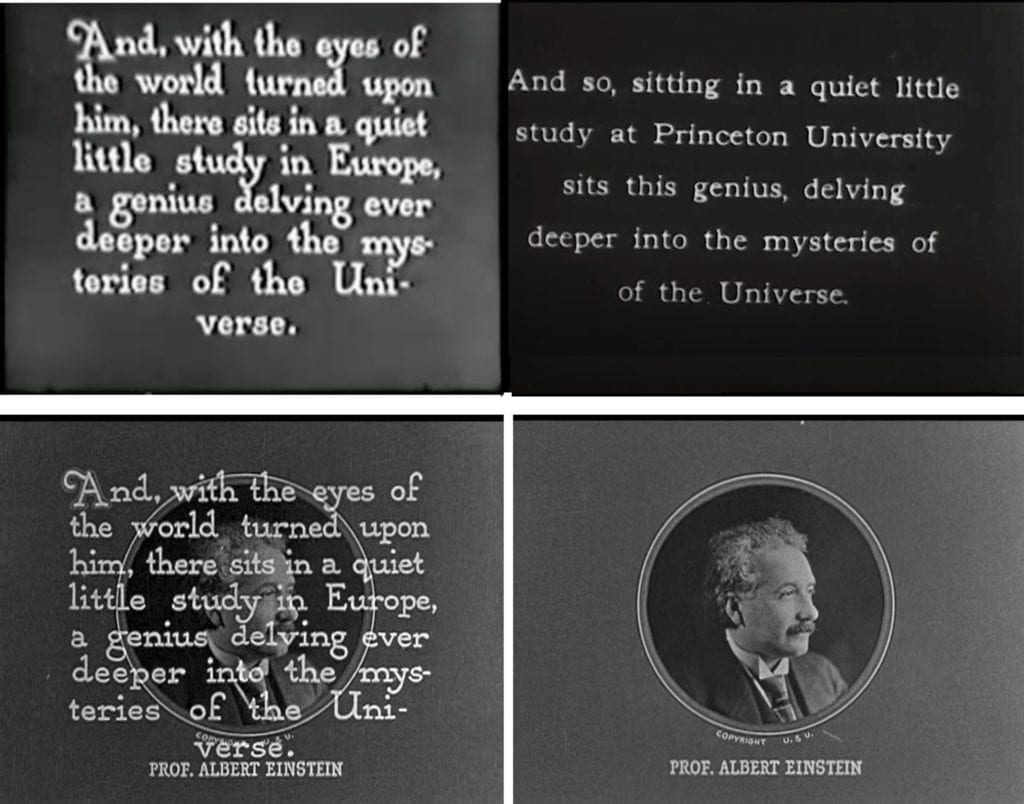

The sophisticated animation and special effects in Wunder der Schöpfung were created by Kornblum’s team using state-of-the-art technology. However, Max Fleischer had already collaborated with the German director on his previous film. Die Grundlagen der Einsteinschen Relativitäts-Theorie (The Basics of Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, 1922) is not known to survive, but its derivative American production does. Made in collaboration with scientists and with Albert Einstein’s tacit approval, The Einstein Theory of Relativity (1923) mixed live action and animation – and lots of text on screen. Running times for the several editions of this film ranged from 15 to 50 minutes.

At last three versions of Fleischer’s Einstein film can be found online. Edwin Miles Fadman (Premier Productions) produced and distributed this mixture of animation and actuality with popular science writer Garrett P. Serviss. The influential film composer Hugo Riesenfeld arranged for first-run screenings of The Einstein Theory of Relativity at New York’s palatial Capitol and Rivoli theaters, where he was house conductor. Fleischer’s end titles refer to a genius in his study in Europe; but a later edition mentions the genius at Princeton University. Einstein moved to Princeton in 1933. The film by then was circulating via 16mm educational film catalogs. Even ten years after the fact, nontheatrical production invested in the shooting of revised end titles. A third ending appears on a Kodascope Libraries 16mm print preserved at the George Eastman Museum. Its final text lap-dissolves to a portrait of the celebrity scientist.

In an issue devoted to the role of short subjects in the American picture biz, Motion Picture News named these two films as having particular appeal in a niche arthouse market. “If the Little theatre, managed by H. G. Weinberg, has a particularly strong supporting subject such as the Einstein Theory of Relativity, or the Ufa astronomical film ‘Heavenly Bodies,’ mention is usually made in the advertisements.” (“Baltimore Exhibs Giving Short Features a Break,” April 19, 1930).

With the introduction of 16mm film in 1923, schools that purchased prints for their AV libraries could screen it for years. This nontheatrical afterlife for educational films enabled this copy of A Trip to the Planets to survive. The opening title likely appeared only as the on-screen introduction to a segment of Ufa’s Heavenly Bodies. However, as evidenced by its radical stylistic shifts, this is a compilation film incorporating shots from other productions. But most of them derive from the German super-production Wunder der Schöpfung.

Although we lack information about the film’s transition from 35 to 16mm, the provenance of this orange-tinted print is instructive, exemplifying how thousands of orphan films often lived on in altered forms and “repurposed” excerpts.

This version of A Trip to the Planets is the only one known to survive. It comes from the library of Mogull Bros., a long-lived nontheatrical distribution company created in the 1920s. In 2009, Library of Congress staff, in consultation with Rick Prelinger, selected 259 reels of 16mm film for a Mogull subcollection assessment. Andy Uhrich, then a master’s student in NYU’s Moving Image Archiving and Preservation program, conducted the study. Uhrich’s assessment traces the print’s migration from the company’s warehouse to Anthology Film Archives to Prelinger Archives to the Library of Congress.

— Dan Streible, NYU Cinema Studies.

— Megan Prelinger is author of the 2010 book Another Science Fiction: Advertising the Space Race 1957-1962.

A longer version of this illustrated essay is here.