Below is an early and longer draft of this essay, revised and published in the book Old and New Media after Katrina, edited by Diane Negra (Palgrave, 2010). Some text below did not appear n the book. Mistakes are made, but I wanted to put the longer text online. — DS

Media Artists, Local Activists, and Outsider Archivists: The Case of Helen Hill

Dan Streible

The traumatic events wrought by Katrina floodwaters in 2005 exposed painful aspects of the social fabric of New Orleans and the nation generally. Class- and race-based inequities were laid bare. Failures of government at every level became obvious. Yet the post-Katrina spotlight also inadvertently illuminated a small but significant community of independent media artists working devotedly in old and new media forms. Some are amateurs, in the purest sense. Others are working professionals making films as an avocation. Still others cobble together piecework and part-time projects that allowed them to pursue their creative talents — getting small grants, work-for-hire, teaching gigs, and freelance projects. Neither dilettantes nor careerists, they integrate creative uses of homemade media into their everyday lives, often affiliating their practice with local social and political activism. The filmmaker Helen Hill, we now understand, is a radiant emblem of this community.

Still coping with the ripples of devastation that followed the “federal floods” of 2005, the New Orleans alternative media community was staggered by the unexpected death of Hill, an artist-activist-animatrice killed on January 4, 2007, by an armed intruder who shot her in her home. Linked to Katrina’s aftermath and the traumatic violence associated with it, Hill’s murder also shone a national spotlight on the alternative media culture of which she was an integral part. That community continued to produce old and new media, even in those worst of times in and after 2005.

Alternative media practitioners in New Orleans are linked via ad hoc means to likeminded ones elsewhere. There exists, in fact, an underexamined but extensive, discrete community of North American media artists who work in the mode of Helen Hill. Our knowledge of their presence is muted by its localism and its disinterest in distribution and profit. With its accessible styles and DIY practices this populist vanguard of filmmakers differentiates itself from the “difficult” works of the better-known avant gardes of New York, San Francisco, Toronto, and other capitals of culture. The funky otherness of New Orleans, which has famously produced so much music and literature of influence, has also been fertile ground for an underseen cinema.

How does this nearly-off-the-grid creative culture sustain itself? How in particular did and does twenty-first-century New Orleans cultivate it, pre- and post-Katrina? during and after Helen? The answers to these questions lead to a reassessment of the contemporary environment for alternative media production and experimental film. In this context the case “NewOrleansHelen” (to use her e-mail handle) illuminates three insights about recent media history and practices. First, this unassuming activist web of media artists not only exists, it has had a tangible, salutary impact on the world beyond the arts sector. Second, this decentralized network of DIY artists has forged a relationship with a new generation of likeminded moving image archivists, who share a devotion to the materiality of film, small-screen projection of small-gauge celluloid, and its noncommercial applications. Third, neither media historiography nor critical theory have adequately accounted for the utopian cinema of which Helen Hill is an exemplar.

&& When she died at age 36, Helen was not a famous filmmaker, but media coverage of her death brought belated but entirely merited recognition of her artistic accomplishments. Helen integrated her creative work into a Goldmanesque life of sweet humanitarian anarchism and her legacy continues to impact independent media arts in New Orleans and elsewhere. In the past few years, memorialization of her life and work and perpetuation of her creative practices have occurred via film restorations, screenings, tributes, benefits, musical performances, workshops, DVD distribution, Web-based media, broadcast coverage, published writing (poetic, scholarly, and journalistic), philanthropy, educational programs, festival awards, and other means.

Helen Hill’s Life and Work

Helen Wingard Hill was born and raised in Columbia, South Carolina, a university town and a capital city, but not one known for filmmaking. Yet here she was exposed to film, via the kinds of alternative means most accounts of media history and culture ignore. Inspired by a classroom visit from documentary filmmaker Stan Woodward in 1981, Helen made two Super 8mm films that year. When she was ten years old, the first was produced as part of a visual literacy program organized in public schools by the South Carolina Arts Commission. Quacks, a comic sketch about a giant duck’s encounter with kids at a school bus stop, included her name alongside five of her fifth-grade classmates. At age eleven, she also made a tabletop stop-motion film at home, The House of Sweet Magic, showing a pixilated gingerbread construction eaten by a dragon. Although it would be another decade before she made another movie, these juvenilia resemble, in style and theme, those she made as an adult.

Attending Harvard from 1988 to 1992, Helen pursued creative writing and participated in a variety of artistic endeavors. On her application she had noted “I would like to learn more about the techniques and opportunities in the film medium, especially animation,” adding that she saw this as a way “to help society recognize its faults and see solutions.”[1] In 1990 she got that opportunity in an animation course taught by Suzann Pitt for which Helen made the hand-drawn, three-minute piece Rain Dance. Like much of her later work it included a musical core, illustrating a song co-written by her then-boyfriend Elijah Aron and her later-husband Paul Gailiunas, with the latter singing it. Vessel (1992) took a similar form, but was based on her poem and added extensive cut-out figures in the style of Lotte Reiniger. Another short film she made during college, Upperground Show (1991), she synopsized as “The underground fairies host a talent show.”[2]

After graduation, she and Gailiunas went to New Orleans for the summer and stayed a year. They soon became a couple, and married in Columbia two years later. Helen left her mark in the Crescent City, publishing an article on experimental animation and her poem “Vessel,” both in the local literary journal, the New Laurel Review. After their Louisiana stint, both Paul and Helen headed off to professional schools. He studied medicine in Nova Scotia, becoming an M.D. in 1997. She accelerated through a program in experimental animation at the California Institute of the Arts, earning an MFA in 1995. At CalArts, Helen enlisted friends and classmates to shoot The World’s Smallest Fair (1995), a pixilated live-action film. Ostensibly a fantasy about monsters attacking fairground-goers, the films features an out-of-control cotton-candy machine as its comic center. Her thesis film Scratch and Crow (1995) demonstrated a more accomplished hand and contemplative soul at work. In rich colors and poetic text she creates a spiritual homage to her favorite animal, the chicken. Nicknamed Chicken from childhood, Helen made the bird a recurring motif in nearly all of her work.

For the next five years, Helen and Paul lived in Halifax, where she joined the Atlantic Filmmakers Cooperative (AFCOOP), teaching animation workshops there and courses at Nova Scotia College of Art and Design. In 1995, she helped found a women’s film festival, Reel Vision. Notes for a Winnipeg retrospective of her work in 2009 offered that, on a list of those “who made a significant impact on the Halifax film community,” the “name that stands out strongest is the late animator Helen Hill. Nobody who worked with or encountered Hill in Halifax has ever forgotten her.”[3]

Through AFCOOP she was able to make Tunnel of Love (1996), illustrating another Gailiunas/Aron song, “Accidental Romance,” with Paul again providing the vocal (this time with his calypso band, Piggy). With its carnival setting and narrative about best friends falling in love, the film can be read as autobiographical allusion to the couple’s experiences of the Crescent City in 1992. A more specific reference to both Halifax and New Orleans appears in Paul’s song and Helen’s film Bohemian Town (2004), which is quite simply a love letter from the new New Orleanians to their Haligonian friends in the bohemian North End. Helen draws the town as a utopia in motion, where skateboarding punk-rockers join with gray-hairs in spray-painting “No War” graffiti, cars cruise by the Food Not Bombs stand, kids and animals dance in the street, and friends bicycle, all living “la vie bohème.” Made for AFCOOP’s thirtieth anniversary, Bohemian Town was completed three years after the move to Louisiana.[4]

The time in Canada was productive for Helen Hill the filmmaker and educator. Having married a Canadian, she became a citizen herself. Canada was, she said, “a great place to get grants.” This she did, making her two most lauded works, Mouseholes (1999) and Madame Winger Makes a Film (2001). She was also able to freelance, doing animation for CBC-TV’s educational series StreetCents (1997-98) and storyboarding for National Film Board projects.

Additionally, she found a niche making silent films that she photochemically processed, tinted, and doctored by hand. For the rest of her life she conducted “Ladies’ Film Bees,” opening her home to amateurs and neophytes, teaching them to shoot, develop, and project Super 8 and 16mm movies in a day. At the 2000 edition of the Splice This! Super 8 Film Festival in Toronto, she curated The Halifax Ladies Film Bee, a compilation of these homemade movies. Otherwise, she conducted community film bees solely as generous acts of social and aesthetic pleasure. The many artisanal films made in this context seldom got projected outside of domestic or community settings, but their audiences . . . [ ].

Helen’s own such films continued her animalier devotions. I Love Nola (1998) was a portrait of her pet cat, whose naming presaged the return to New Orleans. During a residency at Phil Hoffman’s Film Farm in Ontario (aka the Independent Imaging Retreat), she made the hand-tinted Your New Pig Is Down the Road (1999) as

a surprise announcement to her husband that, in fact, his new Vietnamese pot-bellied piglet was awaiting him. The whimsical Film for Rosie (2000) was her portrait of said pig and its blood relatives, each introduced with an intertitle. Mouseholes and Madame Winger were more elaborate projects, crafted over longer periods of time. Each mixed cel, cut-out, and cameraless animation techniques with live action, pixilation, found footage, home movies, voice-over narration, and soundtracks. Although made mostly in Canada, both dealt with the American South. Mouseholes became her signature film, an autobiographical remembrance of her maternal grandfather’s life and death in Columbia. Speaking from a child’s perspective, Helen narrates the story in her own quiet, breathy voice. We hear homemade audio recordings of Helen talking with the dying “Pop,” and of her brother Jake later reading his eulogy. Highly personal expressions of intimacy and grief here infuse a transcendent work with the magical thinking of animation, transforming the human figure into a mouse, who silently, innocently negotiates material and spiritual realms.

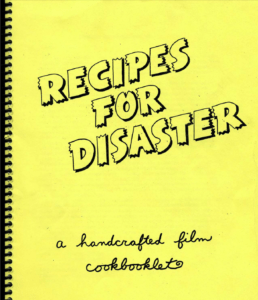

Mouseholes is the most praised Helen Hill work, but Madame Winger Makes a Film may be her most popular. The cut-out figure of Madame Winger serves as an alter ego for the cinephile Helen, adding a giant beehive hair-do to the striped stockings she often wore. With Helen’s whiskey-voiced godmother providing narration in a genteel Southern accent, the ten-minute movie is couched as an instructional film. She explains the fundamentals of film stocks, gauges, processing, and cameras, extolling the fun to be had in making one’s own films. We see Helen’s hands drawing and scratching on unexposed strips of celluloid, and the outcome of such animation. When Hill family movies of 1970s South Carolina appear, Madame tells us they document her youth as “a true Southern belle.” Subtitled A Survival Guide for the 21st Century, the film acknowledges that celluloid is a shrinking presence in the age of digital video.

https://vimeo.com/197137362

In a coda, Helen appears on camera, unfurling a spiral-bound publication, Recipes for Disaster: A Handcrafted Film Cookbooklet. The closing title card instructs that copies of the book can be ordered by e-mailing NewOrleansHelen. With a Canada Council for the Arts grant, in 1999 and 2000 Helen traveled to workshops in Vancouver, Calgary, and Toronto, collecting notes and technical tips from artists making handcrafted cinema and following up with postcards seeking more. Completed for the 2001 SpliceThis! Super-8 Film Festival in Toronto, the self-published anthology continues to circulate among media artists and university production courses. Thirty-seven filmmakers contributed texts and drawings to the Recipes sourcebook. Helen sold copies by mail order, asking only for the photocopying and postage. She added updates in 2004 (“the beloved Kodak 7378 high-contrast film stock was no longer for sale! Substitute 3378e for hand-processing recipes”), and a final one on November 16, 2005.

Since moving to New Orleans five years ago, my husband Paul and I had become part of a fun, progressive, and artistic community. I never expected that it could all disappear so quickly. When Hurricane Katrina hit, our friends scattered everywhere. It has been a strange, surreal time. But people are already coming together in surprising ways to help out and rebuild. This new edition of Recipes for Disaster is a case in point.

Writing from Columbia, in temporary exile, she reported that all of the originals and copies of Recipes — along with 90% of their household — had been destroyed by the flood. Her filmmaking friend in San Francisco, Alfonso Alvarez, “wanted to publish a special post hurricane edition.”

When I first made this book, the whole point was to bring together the scattered community of artists making handmade films. These folks are creative powers, inventing their own recipes and methods. Hundreds more have written me for their own copy of Recipes for Disaster, and so this community quietly grows. Now this DIY film community is coming to the rescue. This is a great help and gets this information out there while I figure out what to do next.

Since that time, photocopies of photocopies continue to circulate and find their way into university courses and libraries. Soon after Helen’s death, a member of the experimental film listserv Frameworks announced his posting of a PDF version on the web, multiplying the number of users.[5]

Since that time, photocopies of photocopies continue to circulate and find their way into university courses and libraries. Soon after Helen’s death, a member of the experimental film listserv Frameworks announced his posting of a PDF version on the web, multiplying the number of users.[5]

Driven by a love for the city and wanting to work where they were most needed, Helen and Paul moved to Mid-City New Orleans in late December 2000. The predominantly African American neighborhood was among the city’s poorest, with 40% of its children in poverty. “Dr. Paul” set up Little Doctors Neighborhood Clinic, providing low-cost medical care for the poor, and together the couple established a chapter of the vegetarian anti-war group Food Not Bombs. Helen soon made a positive impact on the alternative media scene, although she realized that relocation to Louisiana was not a careerist’s move. “Some people wouldn’t live here as a filmmaker,” she said in a 2003 interview, “but I don’t mind being out of the loop, because I’m making my little films, and I can always send them out to the world.” Helen became active in production, exhibition, curating, and teaching, joining in the work of the New Orleans Video Access Center, the Zeitgeist Multi-disciplinary Arts Center, and schools including the New Orleans Center for the Creative Arts (NOCCA).

In 2002, Helen co-founded the New Orleans Film Collective with Wise Wolfe and Dean Pascal. They wanted to “provide a place where people can learn to make films at very low costs and where they can rent gear at a low cost,” she said in an interview for Timecode: NOLA, a local cable television program. “Hopefully with our workshops — and class shows after the workshops — we’ll build up a filmmaking community.”[6] This they did, with Helen offering her handmade movie classes. To process the celluloid, the film collective borrowed the darkroom of a nearby housing collective, Nowe Miasto (Polish for New City). Though she jokingly called it a “punk rock warehouse,” the three-story structure was renovated in 1999 as communal housing, with a library, art and performance space, and meeting rooms for activist groups. After Katrina, Nowe Miasto reorganized in utopian but pragmatic ways. The democratic “limited equity housing cooperative” aspires to generate “safe, affordable, sustainable, and self-determined communities” that are “racially and economically just,” and supportive of “art, music, and activism.”[7] Helen’s later Film Collective workshops also convened at Fair Grinds Coffeehouse, another Mid-City public space supporting local arts and community activism.[8]

The list of creative work Helen did in New Orleans speaks to the unmapped history of filmmaking and media practices under consideration here. Although she created dozens of pieces, a traditional filmography might mislead one to think that Helen Hill produced no films of her own in these six years. Bohemian Town and Madame Winger began in Halifax, but were completed after her move to New Orleans. Her 2001 film 5 Spells survived only on a low-quality VHS assemblage she labeled Early Films of Helen Hill, 1990-2001). Two original films were incorporated into local puppet theater productions, Haley Lou Haden’s By Bread Alone and One Life, Magic Cone, (ca. 2003). In the former, the Queen of Breadland puppet learns her duties by watching an instructional film, which Helen credits to “the National Film Board of Breadland.” Moreover, two completed works were done in tandem with NOCCA colleague Courtney Egan. In homage to experimental cineaste Stan Brakhage and his 1963 film Mothlight, they made the abstract animation Termite Light (2003), sticking the locally indigenous detritivores to 16mm film stock. And, in a high note of her career, in 2004 Helen received a Rockefeller Foundation Media Arts Fellowship. With it she began production of a longer-form animation about a local artisan, Florestine Kinchen, whose dressmaking she hoped to save from obscurity.

Yet another creative achievement from the New Orleans years is the series of short on-line movies Helen and Paul completed each October. For the collective public art project Gothtober, thirty-one media artists each contribute a Flash animation for “Gothtoberfest.” The Halloween-themed website, produced by Juliana Parr, is formatted like an Advent calendar. For their window, Helen annually illustrated an original song that Paul sang and recorded. The first, Rosie Wonders What to Wear (2003), featured a song called “What to Wear,” with drawings and photographs of the family pet pig dressed in various Halloween costumes. It includes a sadly ironic end-title: “Ms. Hill also runs Films for Funerals, a company which assists people as they direct short personal films, made to be screened at their own funerals.” Birth and love, however, were the themes of Gothtober Baby (2004). Posted shortly before the birth of their son Francis Pop on October 15, 2004, the dark comedy of the song and drawings advise, in Helen’s poetry: “A perfect chick is what she’d like but you can never tell / until it exits, what it’s like from toe to fontanelle / But every mom should love a child distorted or obscene / and don’t forget to dress it up every Halloween.”

The following year, barely more than a month after Katrina, Helen and Paul persisted with their Gothtober contribution Halloween in New Orleans (2005). Its on-screen dedication was to “all the neighborhood kids who filled our porch last Halloween…. Hurricane Katrina emptied our neighborhood and scattered all of them to unknown places.” As drawings and photographs of the couple’s flooded home parade by, the dark lyrics laugh in the face of death and chuckle at catastrophe.

Now the city streets are empty ‘neath the pale white moon

Instead of little children there is only gloom

The houses are all haunted, that is just assumed

Down in New OrleansNow you can see the ghost of the Zulu King

And you can see the ghost of the Voodoo Queen

You can see the ghost of just about anything

’Cause everyday is Hallowe’en down in New Orleans.

The use of self-made media to inspire continued with A Monster in New Orleans (2006) in which The Creeps (Paul Gailiunas, with Keith Rogers and Christian Repaal) perform the eponymous rockabilly song. A green cut-out monster interacts with Helen’s black-and-white photographs, taken “in early October, over a year since the hurricane,” we are told. “With the burnt out houses, doors left wide open, gigantic trash piles and overgrown yards, New Orleans is a perfect hideout for monsters.”[9] As modest as these productions are, they are part of an alternative media community’s efforts to rebuild and fortify itself. Against all expectations, they confront the monsters of despair that threatened the returning diaspora and resound with the genuine cheer and optimism of a New Orleans that plays on while national media dwell on the desolation. The life-affirming power of homemade media is even further demonstrated in the Gothtober entry Francis Pop’s Hallowe’en Parade (2007). The backyard Super 8 film “by Francis Pop and Paul Gailiunas,” made “With Love for Helen,” shows the couple’s three-year-old son modeling costumes.

More remarkable is Cleveland Street Gap (2006), a second Hill/Egan production. A cinematic elegy, it merges distressed fragments from Helen’s pre-Katrina home movies (shot in summer 2003) with Courtney’s post-Katrina video documenting the same locations in June 2006. Soft-focus black-and-white images of Paul joyfully playing with children on Cleveland Avenue match-dissolve to sharp color video of their abandoned shotgun house. Helen’s graffiti on the wall of the front porch reads “We are all okay, cats, baby Pop, even Rosie the pig!!! We miss y’all! {heart}, Helen & Paul.” The film-video collaboration was done with Courtney Egan in Louisiana and Helen still living with her family in South Carolina, trying to “figure out what to do next.”

Cleveland Street Gap was a brave creative response to disaster and grievous loss. Its emotional power and personal resonances represent the type of work that DIY media artists and amateurs can achieve, and which commercial film and television cannot match. Most well-intentioned independent documentary features also fall short of such empowering work. For example, The Axe in the Attic (2007) documents Ed Pincus and Lucia Small’s response to watching the television news coverage of New Orleans drowning. Living in New York, they drive south, admitting stereotypical trepidations about Dixie. The impotent feelings of rage, fear, and grief they hoped to counter by going to Louisiana are instead repeated. They find their role as social documentarians dismissed by the magnitude of destruction and the despair of Katrina evacuees. Within the film itself, the most powerful footage is amateur home video shot by Linda Dumas, a working-class, African American woman, who narrates the flood destruction in real time. “What you’re looking at,” she tell us as we see a street with automobiles under water, “is the first floor apartment in the St. Bernard Housing Development, where I happen to live.” She turns her camera on herself, creating a tight close-up, and yells at us “And all my shit is gone!” Based on what we see of Dumas’s footage in The Axe in the Attic, her brave, defiant, and raw video is as communicative and expressive as any professional reworking of it could be.[10]

Moments such as this are exceptional, but not unique. Historians and archivists increasingly value noncommercial video documentation, taking particular interest after the events of 2005. The University of New Orleans has partnered with George Mason University’s Center for History and New Media to create an ambitious project, the Hurricane Digital Memory Bank (HDMB). In “The Post-Katrina Documentary Impulse and New Media” (2007), UNO social historian Michael Mizell-Nelson describes how the initiative valorizes both raw amateur video and edited pieces.[11] Examples of the latter include the curated, on-line New Orleans Video Access Center Short Documentary Series, done in the mode of community-made activist production. In its mission to “collect, preserve, and present” digital documents related to the experiences of hurricanes Katrina and Rita, the HDMB includes user-submitted video. Under the heading “St. Bernard Parish, Louisiana after Katrina on Video,” an exemplary item is catalogued simply as “Katrina.wmv.” Videographer Benjamin Chappetta shoots a long traveling shot from a moving vehicle driving down a desolate street, past dozens of utterly wrecked buildings. Simple in execution and powerful in revelation, it arguably surpasses in aesthetic value the more calculated opening traveling shot in Godard’s Weekend.[12]

Similarly powerful are Helen Hill’s twenty-first century home movies, particularly those she shot in New Orleans. The fact that she created more than 80 reels of Super 8 footage simply to document her family, everyday life, and community would have, in other circumstances, gone unmentioned when discussing her work as a filmmaker. But with the erasure of the old New Orleans, these films take on greater documentary value. Helen shot backyard scenes, pets, and family outings, of course. But she also recorded parades, public protests, gay pride events, performances, their own local “International Flag Burning Day,” social gatherings of the city’s creative class, and funky underrepresented parts of daily life.

The Hill-Gailiunas “home movies” are not exactly typical of the millions of small-gauge amateur films that middle-class families shot throughout the twentieth century. As a film purist, she chose not to take up the more convenient video camera that had been the home recording device of choice for a generation. As an artist, she was cognizant of how spontaneous shooting (at home or outside a destroyed home) was part of her aesthetic. In her first post-Katrina experimental film, she melded the home movie and her painterly style. The untitled five-minute collage, completed early in 2006, consisted of fragments of flood-damaged Super 8 films Helen shot in New Orleans. After hand-cleaning the tiny strands, she had Alfonso Alvarez blow them up to 16mm using an optical printer. Many of the images were of her infant son, Francis Pop, who was not yet a year old when Katrina struck. With emulsion scarred and swirled in irregular fashion, the film resuscitates its original subjects while also evoking ephemerality and mortality.

The “little films” that Helen was “sending out to the world” included not just her own, but also the modest works of many who discovered that they too could make a film for fifteen dollars. Helen helped cultivate local film culture by setting up screenings of films and performances by local artists. In August 2006 she worked with an ad hoc group of archivists to program the first Home Movie Day in New Orleans. The organizers, the Center for Home Movies, wanted to pay special attention to the needs of the city that first year after Katrina. As I discuss below, this event was part of Helen’s participation in the world of media archiving and film preservation. It was a consequential step into another kind of avant garde, that populated by the self-described “outsider archivists” and “anarchivists” who have been at the leading edge of archival practice during the past decade.

As New Orleans exiles in 2005-06, Helen and Paul lived with their son in her parents’ home in Columbia for a full year. Paul returned at the end of September to survey the damage to the Cleveland Avenue house, rescuing their two cats. In another brave response to Katrina, Helen and Paul made home movies of their brief return to the flooded house in October 2005. Pantomiming for the camera in respirator masks and latex gloves, they document how high the water had climbed. Far from mourning the loss of material possessions, they marvel at how much jetsam is heaped on the curb. Helen inserts close-ups of recovered photographs and keepsakes, damaged but also beautiful after stewing in the toxic muck. Barely two weeks later, back in South Carolina, she was already making new work: recirculating the November 2005 edition of Recipes for Disaster, collaborating with Courtney Egan, and making the 16mm collage with Alfonso Alvarez.

Early in 2006, I received a typewritten note from Helen. She told me of her interest in attending the Orphan Film Symposium in March, noting the serendipity of landing in her hometown at the time the event was taking place at the University of South Carolina. Hearing about the loss of her films and her new collage, I invited her to present at the symposium, which she did on the closing night. Later I discovered she had met several symposiasts who were advising her on how to salvage the seemingly unsalvageable prints. Introducing her screening, Helen reported how the first film laboratory she contacted told her that her films could not be saved. She also presented a Katrina artifact to fellow filmmaker Bill Morrison, who was also screening new work that evening. When Helen and Paul found a mud-caked VHS copy of Morrison’s Decasia (2002) in their recovery efforts, they saved it as a souvenir for him. In the ensuing months, Helen continued her DIY film rescue and began to collaborate with the archival professionals she met in Columbia.

By August 2006, Helen persuaded her husband that they should move back to New Orleans, where they were needed. The family rented a small house in the Marigny neighborhood and Paul resumed his medical practice at a nearby public clinic. Helen continued making her handmade films, shooting Super 8 movies of her growing son, and teaching at NOCCA (now just a few blocks away). It had been an eventful couple of years for Helen Hill: finishing Bohemian Town, becoming a Rockefeller Media Arts fellow, giving birth to Francis Pop, fleeing a hurricane, losing her material possessions to the flood, living as an “exile” in her childhood home, salvaging her surviving films, making new work with them, re-issuing Recipes for Disaster, showing at festivals, laboring through the move back to Louisiana, curating programs, writing, holding open studios, teaching. But through the fall of 2006 life returned to its pre-Katrina rhythms, albeit in a less vibrant, less populated New Orleans. As late as New Years Day 2007 Helen was shooting more home movies. So it was with an extreme sense of tragedy that news circulated of the death of such a beloved community builder and luminous artist was killed in her home by an act of random violence. The unidentified intruder also shot Paul three times, though he escaped with relatively minor injuries. His body completely shielded baby Francis from the bullets.

Helen Hill’s death became a rallying point for local protests about the lack of police protection for Katrina-ravaged communities. National press coverage coupled her life as a spirited community builder in the arts with that of Dinerral Shavers, a 25-year-old musician and teacher murdered that same week – along with seven other citizens of New Orleans. He had already become associated with the plight of New Orleans, a resident of the Lower Ninth Ward interviewed in Spike Lee’s HBO documentary When the Levees Broke (2006). Both Shavers (African American) and Hill (white) received traditional jazz funeral processions, further linking them as public figures who transcended a stark racial and class divide. Journalist Noah Adams said “their stories were entwined with the New Orleans struggle.” Television networks devoted prime-time programs to the cases. CBS News’ 48 Hours Mystery called their murders “symbolic of the breakdown” in social order. CBC News offered that the shooting of Helen and Paul “became a symbol of all that’s wrong with New Orleans.”[13] More important than these traditional media reports, Internet postings and productions became central to the sharing of information and personal expressions of loss in regard to the deaths of Hill and Shavers. Myspace.com hosts a Dinerral Shavers Official Memorial Page. Friends set up HelenHill.org, which continues to present news, letters of remembrance, photos, videos, and audio recordings related to her life and work.

The narrative of Helen Hill’s life and work did not end with memorialization. Instead, an unexpected confluence of forces has extended the creative work of this DIY film artist, at a time when “new media” has supposedly displaced celluloid-specific production and projection. After her passing, more people saw her work than ever saw it in her lifetime. Old media (film prints, television broadcast) and new media (digital reproduction and display) worked in tandem. In turn, works by other filmmakers are getting preserved, exhibited, and recognized.

Outsider Archivists, Anarchivists, and Orphanistas

A few days after Helen’s funeral, her mother and husband called me for advice about the care of the scattered film elements. Festivals, nontheatrical venues, and individuals were asking to show the films, but few projection copies were available. Calling upon regular participants in the Orphan Film Symposium, we soon gathered a group of archivists, filmmakers, scholars, curators, and advisors who collaborated to make the surviving works available. Two months later, nine Helen Hill films had been preserved and two sets of new 16mm prints were circulating, starting with the 2007 Ann Arbor Film Festival (which was dedicated to her). A tenth, Rain Dance, soon followed. The work of such a radically independent filmmaker is seldom afforded full preservation. The results of this collaboration are therefore worth documenting.

The ad hoc nature of this project is characteristic of a recent turn in the overlapping fields of archiving, scholarship, curating, and media production. The turn involves not only the comingling of these discrete professions, but also a new kind of valorization, in which content and artifacts formerly neglected are now deemed worthy not only of study but of the expenses of archival preservation. Amateur films, home video, fragments, industrial films, race movies, experiments, found footage, science films, and other works with no perceived commercial value (sometimes abandoned by their owners) have received new life among archivists, artists, and academics. The umbrella term orphan film took hold in the late 1990s. The phrase developed an official connotation when it was used in federal legislation authorizing the National Film Preservation Board (NFPB) and Foundation (NFPF), and in Film Preservation 1993, an influential report from the Librarian of Congress.[14]

By 2001, three playful neologisms informally entered the argot of preservationists and their allies: orphanista, anarchivist, and outsider archivist. Underlying each are principles embraced by many professionals in the field. Archival practices should be: holistic (access and use are integral to preservation, not separate), democratic (appraisal considers the cultural value of each film independent from commercial value or copyright status), and communal (partnerships formal and informal are often needed to save “at risk” films). These made the Helen Hill film preservation project possible. The first term originated at the second Orphan Film Symposium, where I greeted the participants as “orphanistas” — meaning passionate advocates for neglected moving images. After using it again at the 2003 Margaret Mead Film and Video Festival, I was surprised to find that the scholarly journal American Anthropologist published an essay entitled “The Orphanista Manifesto”![15]

Also in 2001, members of the Association of Moving Image Archivists began to read an anonymously circulated document, “The Anarchivists’ Manifesto,” emanating from the Alaska Moving Image Preservation Association. Accompanied by a mock insurrectionary logo (a clinched fist in a power salute, holding strips of film), the text encapsulates the ethic that many within the new generation of moving image archivists embrace. In order to “save the world’s cultural and historical heritage,” film archivists must “fight against authoritarian and hierarchical tendencies” in institutions, provide “maximum public access to all collections,” and “confront the gatekeepers and powerbrokers who control political power and major funding sources.”[16] In reality, many of those who side with this battle against bureaucratic lethargy work for archival institutions, which are anything but anarchical. Their activism is extramural.

The same is true for the person I first heard call herself an outsider archivist. In 2001 Liz Coffey was completing the Selznick School of Film Preservation program. She worked as a projectionist in Boston, affiliating with independents and avant gardists. However, her punk sensibilities did not prevent her from finding a position in the least outsider-ish institution. In 2006, she became the Harvard Film Archive’s conservator. A year later, serendipitously, she became a custodian of the Helen Hill Collection. Coffey is part of the first generation of specially trained film archivists. They understand traditional practice, but also bring a revisionist curatorial perspective. Like the latest wave of film historians, they are interested in neglected and marginalized works. Screening them in public settings is integral to understanding their significance and to preserving such artifacts. Watching unidentified home movies, silent newsreel outtakes, and antiquated medical films projected brings cinematic pleasure and, in some instances, unexpected discovery.

Helen shared this sensibility and was of course an instigator of screenings. But it was the destruction of her possessions that brought her into contact with likeminded archivists. As evidenced by Recipes for Disaster, she was familiar with the photochemistry of film emulsions and stocks, as well as handling exposed film. She was self-primed in the meticulous cleaning of prints salvaged from New Orleans. With some advice from expert and orphanista Larry Urbanski, Helen worked on her own for several months. In 2006, Kara Van Malssen contacted her. An NYU graduate student, she was writing a thesis, Disaster Planning and Recovery: Post-Katrina Lessons for Mixed Media Collections, in the Moving Image Archiving and Preservation program (MIAP). Van Malssen learned of Helen through her University of Florida professor Roger Beebe (coincidentally an experimental filmmaker and native of Columbia, South Carolina). Helen’s disaster became a case study, alongside the Louisiana State Museum, the Hogan Jazz Archive at Tulane University, and New Orleans community radio station WWOZ-FM.[17]

Along with her MIAP classmates, Van Malssen participated in the 2006 edition of the Orphan Film Symposium. That week she spent time inspecting films with Helen. They met with the experimental filmmaker Bill Brand, who runs a small-gauge film preservation lab, BB Optics. Brand was also teaching the MIAP film preservation practicum. By the end of the symposium, she had charmed many participants.

Afterward, Helen corresponded with Dwight Swanson of the Center for Home Movies. By May 2006, they were planning the special New Orleans edition of Home Movie Day (mentioned earlier). She scanned frames from Madame Winger showing Paul wearing an I-heart-Super 8 T-shirt, which became the postcard distributed to promote Home Movie Day events around the world. A second postcard depicted Madame Winger at home with her 16mm projector. Swanson asked her to assemble a screening at the Zeitgeist Multi-Disciplinary Arts Center featuring home movies and personal films “by the New Orleans filmmaking community,” adding this idea was “almost entirely the result of seeing your films at Orphans.”[18]

The Zeitgeist screening on August 11 made an impact. Joining Swanson and the locals were archivists Brian Graney (UCLA), Kelli Hicks (Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum), and Lauren Sorenson (NYU student interning at Appalshop that summer). One of the Nola media makers Helen invited was George Ingmire, who screened his late grandfather’s 16mm home movie with an accompanying narration on audiotape. Think of Me First as a Person was Dwight Core Sr.’s edited compilation of scenes he filmed of his growing son between 1960 and 1975. This portrait of Dwight Jr., narrated by his father, is also a love letter to a child born with Down syndrome. Find it the most stunning home movie he’d ever seen[19] He showed it at a meeting of the National Film Preservation Board, to which he had recently been appointed by the Librarian of Congress. In December 2006, the Librarian named Think of Me First as a Person to the National Film Registry — a rapid road from partially completed home movie to canonized exemplar of the amateur film! But the road did not end there. In 2008, a beautiful 35mm print of the film debuted at the Orphan Film Symposium in New York. Haghefilm, a high-end preservation lab in Amsterdam, donated the digital restoration work as a symposium sponsor. Working with Ingmire, Haghefilm also married the soundtrack and image for the first time. His grandfather’s film is now archived at the Library of Congress. Ingmire subsequently released a DVD version through his New Orleans-based production company.[20]

Such treatment is of course exceptional for a home movie, but it also exemplifies the kind of activity that Helen, the New Orleans animateur, often instigated. The August 12, 2006, Home Movie Day that followed brought a modest public turnout to the French Quarter, but included the recently made Kalypso’s New Orleans, a “video diary by a 10-year-old girl named Kalypso.”[21] The next morning, Helen and Paul took the visiting archivists to picnic on the porch of their flooded former residence, an event documented in a lovely silent Super 8 film by Kelli Hicks.

Working with Helen throughout the summer and fall 2006, Swanson and Katie Trainor applied for grants that would allow the Center for Home Movies to preserve some of her home movies of pre-Katrina New Orleans. Shorty after her death, the Women’s Film Preservation Fund awarded the first one. The Maxine Greene Foundation for Social Imagination, the Arts, and Education then funded three more films to be preserved for the 2008 Orphan Film Symposium. To select which pieces of Super 8 for preservation on 16mm film, Swanson and Kara Van Malssen completed an inventory. Their descriptions of the content reveal even more diversity of material in the “home movie” collection: camera tests for other films, sequences made for The Florestine Collection, the Queen of Breadland instructional movie, animated promos for the New Orleans Film Collective, Madame Winger outtakes, a found film entitled New Orleans Voodoo and the Past (undated), and unidentified reels.[22]

This gallimaufry of material was what had to be assessed upon Helen’s passing. How to make the finished works available? What should become of the collection? After surveying the options, the family agreed that the Harvard Film Archive was the best fit. Helen, her brother, stepfather, husband, and many friends and collaborators were alumni. Three of her films were produced at Harvard. The archive has: a cinematheque that regularly shows experimental and independent work, a conservation facility, accessible collections, a research-friendly environment, a staff experienced in handling small-gauge films and artists’ work, and an active preservation strategy.

Before making long-term arrangements, the family and the archive moved swiftly to get films ready for preservation and printing. In Columbia, Paul and filmmaker Laura Kissel made a preliminary inventory. In February, Helen’s parents, Becky and Kevin Lewis, drove the films to Colorlab in Rockville, Maryland, where they met with Russ Suniewick. He had been introduced to Helen and her work at the previous Orphan Film Symposium. Colorlab began preserving the films pro bono. Then, on March 14, a group assembled at the Lewis home in Columbia. Haden Guest, director of the Harvard Film Archive, joined Kissel, Brand, Van Malssen, and myself. With Paul we screened Colorlab’s check prints of nine films. By the end of the day, Guest and the family had arranged to establish the Helen Hill Collection at the Harvard Film Archive. One week later, the Ann Arbor Film Festival opened with nine newly restored films in its tribute to Helen Hill. Harvard Film Archive began distributing the package of 16mm prints to other festivals and venues.

A tenth film, Rain Dance, was soon added. Its restoration required special treatment. Only a workprint survived, without the soundtrack. The NYU film preservation class taught by Bill Brand did the work in spring semester 2007 (one of the students being Lauren Sorenson, who had worked with Helen on Home Movie Day New Orleans). The original soundtrack featured Paul Gailiunas singing and playing guitar. In February, still recovering from the gunshot wounds to his hand and arm, Paul re-recorded himself singing and playing the Rain Dance song. From Vancouver, he e-mailed an MP3 audio file to Brand in New York. Musician Matthew Butterick, who had performed accordion and glockenspiel accompaniment, re-recorded these parts and e-mailed the file from Cambridge, Massachusetts. After Paul mixed the audio with the New York restoration company Trackwise, Brand had them digitally “stretch” the music to synchronize with the film’s running time. The DVD and 16mm copies of Rain Dance now available are the marriage of this 1990 film and 2007 audio recreation.

After a year of memorial screenings, a more celebratory tribute opened the 2008 Orphan Film Symposium. It brought together not only the outsider archivists and orphanistas, but also notable insiders who shared an admiration for her work and a dedication to film preservation. We entitled the event “Anywhere. . . A Tribute to Artist-Activist Helen Hill,” an allusion to Mouseholes, in which she asks her dying grandfather if he knows where he is, and he replies “Anywhere.” The Academy Award-winning animator John Canemaker delivered an appreciation of her work and life filled with “angelic sensuality, sensitivity, and fun.” Mouseholes, “a visual haiku and her masterpiece is,” he offered, “quintessential personal-statement cinema: rough-edged, heartfelt, intelligent, daring.” More than just an animator, “Helen was a total filmmaker.” As an experimenter, she was part of a community that produces a “refreshing alternative and antidote to committee-constructed, soulless, special effects-driven commercial cinema.” Although Canemaker never met Helen, he said that who she was “is all there” in the films, “innocence, joy, ecstasy, flying, freedom, love, lots of love — love of filmmaking, love of being an independent woman.”[23]

Three other parts of the evening — a dedication, an award, and a song — demonstrated the fusions of insider/outsider and artist/activist. Haghefilm, in addition to debuting Think of Me First as a Person with George Ingmire, contributed another restoration to the symposium. The lab presented the animated short Helen La Belle (1957), by the German filmmaker Lotte Reiniger. The Deutsches Filminstitut printed a dedication on the end credits: “In memory of Helen Hill (1970-2007), animator and Lotte Reiniger devotee,” connecting the DIY artist with an internationally celebrated one.

Next, the symposium presented its first Helen Hill Awards to James Kinder, a first-time student filmmaker at the New School, and Naomi Uman, a midcareer experimentalist. Participants in the 2006 symposium, unsolicited, had given money in 2007 to establish an award in Helen’s honor. Others followed. The University of South Carolina and NYU worked with her family to announce a prize honoring “radically independent, innovative filmmaking of exceptional talent.” Adding a professional patina to the award, Kodak (unsolicited) contributed a supply of raw stock to the award recipients.

However, the program conveyed the artist-activist’s anticommercial values and her New Orleans joie de vivre. The newly preserved home movies shown were shot by Helen in her Marigny neighborhood on the Fourth of July, 2003. Through the distressed emulsion we see, in addition to the festivities of International Flag-Burning Day, Thomas Little, a friend she filmed masquerading as Jacqueline Kennedy. (He subsequently learned filmmaking at Helen’s workshops and now carries on her practices, making hand-processed and animated films.)[24] Pete Sturman, a musician friend who had fled Katrina for New York, performed “Emma Goldman,” Paul and Helen’s rock homage to the anarchist agitator. (“She told me that the state is my enemy /the lady on the left / saying property is theft / . . . But J. Edgar Hoover /couldn’t move her from my heart” — appropriate for the symposium’s theme of “the state.”) A duet followed of “My Pink Bike,” a joyful, childlike Hill/Gailiunas ditty. Performing a live accompaniment on autoharp, Kelli Hix showed the front-porch film she made of Helen and Paul with Home Movie Day friends in 2006.

Other filmmakers, from New Orleans, Canada, and South Carolina, showed little-seen films that are part of Helen’s legacy. Courtney Egan introduced Termite Light and Cleveland Street Gap. Torontonian John Porter presented Phil’s Film Farm (2002), which he had dedicated to Helen Hill, seen throughout the piece processing her own films during one of her three residencies at Phil Hoffman’s retreat. The tribute opened with a previously unscreened outtake from a video by USC students documenting the 2006 symposium. In shooting Orphan Ist. (a reference to Gustav Deutsch’s archival compilation series Film Ist.), they had recorded an interview with Helen in which she described her work in relation to the orphan film rubric.[25]

Fittingly, even this mini-DV recording was presented on celluloid. Helen and her Recipes for Disaster cohorts represent perhaps the last moving-image makers who choose to shoot, edit, and project exclusively on film, eschewing video. As the industrial mode of movie production and exhibition has gone digital, the love of film qua film continues in the artisanal mode. Madame Winger tells us if Kodak ever stops manufacturing Super 8mm film, “don’t fret, it still will be made” by small companies. However, Madame Winger also imagines a near future in which individuals may have to make and process their own motion-picture film in bomb shelters. (Uncannily, Helen’s film released in summer 2001 asks “fellow filmmakers” “what will you do” in the event of “gigantic terrorist attacks?” And her accompanying Recipes drawing envisages “a worldwide recession.”) For the orphan film movement, the issue is preservation. Movies preserved on film are likely to endure more than a century, while video and digital formats must be migrated every decade. Hence Colorlab’s bequest, printing the videotaped interview to 16mm film (a very rare phenomenon in video preservation), optimized its archival lifespan.[26]

“Anywhere. . . A Tribute to Artist-Activist Helen Hill” included one other film as its surprise finale. Unbeknownst to nearly everyone, Becky Lewis found the Super 8mm print of The House of Sweet Magic only days before the New York screening. She conspired with Colorlab to unveil the rediscovery, which revealed a perfect continuity between the eleven-year-old’s use of film and the hand visible in her mature body of work: an animatrix with a childlike sense of joy and fun, a maker and pixilator of handmade objects, an animalier whose creatures could be monstrous as well as endearing.

The Legacy of Utopian Cinema in the 21st Century

To a large degree, the reception of Helen’s films has emphasized their sweetness, levity, and life-affirming celebrations of love. In 2008, for example, the Robert Flaherty Film Seminar posthumously honored Helen with its Charles Samu Award, given to animators whose work conveys “a universal message illuminating our sense of world community.” Certainly, her art affirms that. The flag of world-{heart}-nation she drew for “Where Will You Be in the Next Century?” (see figure) epitomizes the utopian vision that threads through all of her work.

However, the work is also political, not simple or naïve, as some facile descriptions put it. Although Helen’s creative output accentuates optimism, love, and uplift, it also sees these as correctives to an inequitable social order. Her films take as a given that a world dominated by money, militarism, and belligerent nationalism must be made better by people doing things to serve basic human needs. She lived the life of a utopian anarchist, a citizen of the world, residing in the creolized port of New Orleans, the bohemian town of Halifax, the worldly world of Los Angeles, the creative community of Cambridge, while also remaining a creature of Carolina. The loaded word anarchist may not be the first that comes to mind after viewing Mouseholes or Madame Winger Makes a Film, but anarchism is a key concept for understanding the extended group of DIY media makers of which Helen and Paul were a part.

Anarchy here does not refer to the common conception of lawless chaos and nihilistic destruction, but rather its opposite. The anarchism of the New Orleans Film Collective, Food Not Bombs, or Nowe Miasto is a belief in autonomous individuals participating in the building and sustaining of local communities. The domination of social hierarchies and nation-states is to be countered by humanitarian actions and direct democracy. “Helen believed deeply, at the core of her being, in the equality and dignity of all people,” her husband wrote in an open letter to the people of New Orleans after her death. “She took part in Eracism meetings, the progressive Gillespie Community Breakfasts, and political rallies to help bring back New Orleans in the most fair and inclusive way.” Or, to refer again to Helen’s Recipes for Disaster cartoon panel, this philosophy is about the making of “a better world, where all work and industries are devoted to serving basic human needs,” a world in which everyone has enough to eat. Although she did not label herself with an ism, her cookbooklet slyly alludes to The Anarchist Cookbook (1971).[27]

This political inflection is also part of the twenty-first century DIY phenomenon. In the 1950s and 60s, the marketing of Do It Yourself books to middle-class home owners extended into dozens of how-to manuals for amateur filmmaking.[28] However, contemporary DIY culture is rooted in an anti-corporate grassroots practice, as profiled in Faythe Levine’s 2008 book and 2009 documentary Handmade Nation.[29] Writing about the New Orleans Craft Mafia’s screening of the movie, a local reviewer likened its DIY subjects to a revolutionary guerilla movement, in which “do-it-yourself toilers in the craft movement exude a similar rebellious spirit.”[30]

Among all of Helen’s handmade work, the film that best encapsulates this connection between her art and activism is the one she left uncompleted. Her 2004 Rockefeller fellowship kickstarted production of The Florestine Collection. Conceived as a hybrid of animation and live-action documentary, it would tell the story of a collection of distinctive handcrafted dresses Helen found on a trash heap in 2001, on her way to a Mardi Gras parade. After saving some one hundred dresses, she identified their creator. Florestine Kinchen was an unheralded African American seamstress in New Orleans when she died at age 90. Helen got to know her lifestory through Kinchen’s family and fellow churchgoers. She recorded interviews and filmed the people with whom she was working. At the time of her death, she had also storyboarded The Florestine Collection with cut-out figures to be animated. Her planned narration would highlight issues of race and class disparities in the city, told from an autobiographical point of view. Comparing the life of two New Orleans women who made handcrafted work, it would be her longest and most in-depth film. The materials were powerful enough for a museum exhibition to be mounted in 2007, featuring many of the Kinchen dresses alongside objects from the pre-production of the film.[31]

However, The Florestine Collection did not remain unfinished. “A film by Helen Hill completed by Paul Gailiunas” reads the opening title on the thirty-minute 16mm production, scheduled to preview at the 2010 Orphan Film Symposium in New York and to premiere in her hometown. Columbia’s nonprofit repertory film center, the Nickelodeon Theatre, also confers a Helen Hill Memorial Award at its annual Indie Grits Film Festival, given to “the best work by a female filmmaker, in honor of Columbia native and celebrated animator, filmmaker and teacher Helen Hill.” The Nick also continues a long tradition of animation workshops for children. In 2009, it programmed a DIY Animation Celebration showing Helen’s films, followed by a “make your own flip book” session. Film scholar Susan Courtney, a co-founder of the Orphan Film Symposium, offered an inspirational anecdote about the impact of this legacy work on her own daughters. “Chloe, a huge Madame Winger fan, is very keen about all this. After I told her the idea for the new center at the Nick she said, ‘Does that mean we could WATCH Madame Winger in the theater and then go right next door and MAKE a film?!’”[32]

That pedagogical legacy is even more pronounced at the New Orleans Center for the Creative Arts, where Helen taught. Her cameraless animation workshops have continued, Courtney Egan writes, “as a kind of memorial — part of how we continue Helen’s legacy here.” In 2007, the community’s annual twenty-four hour Draw-a-thon included screenings of her work.[33] Such is the impact of this, that now a young artist can be found describing her first 16mm hand-painted film as “inspired by Stan Brakhage, Helen Hill, and other avant-garde/experimental filmmakers.”[34]

However, there is also a gulf between the influential “essential cinema” of Brakhage and his cohort and the world of Helen Hill. The humor, love, whimsy, sweetness, and accessibility (even to children) of Helen’s films easily differentiate them from the experimental films usually taken as emblematic of the post-WWII American avant garde. The latter is generally represented by the work of structuralists, contrarians, and male individualists — Brakhage, Hollis Frampton, Jonas Mekas, Ken Jacobs, Kenneth Anger, et al. This artists’ film culture has historically been characterized as filled with conflict, internecine grudges, denunciation, and darkness. As the New American Cinema Group famously expressed in its 1961 manifesto: “we don’t want rosy films — we want them the color of blood.”[35] Helen wanted rosy films, figuratively and literally. Flowers were a motif in her work, both animated and photographed (and of course her pet pigs were Rosie and Daisy). Throbbing red Valentine hearts were another. Hers was, as Egan puts it, a cinema of optimism. Even when it dealt with death, resurrection followed. Scratch and Crow concludes with the written, biblical-sounding evocation “If I knew,/ I would assure you we are all / Finally good chickens / And will rise together, / A noisy flock of round, / Dusty angels.”

Certainly Helen’s work also shares traits with the canonical avant garde. Like the Group, she preferred films “rough, unpolished, but alive,” rather than “false, polished, slick.” She knew that Mekas, Brakhage, Jerome Hill (no relation), and other cineastes valorized the art of amateur cinema. (“I studied home movies as diligently as I studied the aesthetics of Sergei Eisenstein,” said Brakhage.)[36] Helen also taught her students the history of animation, showing experimental work by Lotte Reiniger, Len Lye, Norman McLaren, and other artists who influenced her. These two schools came together briefly when Anthology Film Archives, epicenter of avant garde American cinema, hosted a retrospective, The Life & Films of Helen Hill, in October 2007.

Yet the newer, parallel cinema of utopia remains fundamentally different in principle and practice. It is a collective that shares its tricks of the trade, comprised of people whose films are made for an audience of family, friends, and lovers as often as for festival exhibition. Helen never offered her films for distribution, not even through cooperatives. She showed at festivals of course, but more often in small nontheatrical venues, backyards, and homes. Hers was an interpersonal cinema experience. She never commercially released on video, television, or (save for the three Gothtober pieces) the Internet. When her family released a posthumous DVD compilation, The House of Sweet Magic (2008, distributed by Peripheral Produce), they did so with some reluctance, knowing that she projected her films as films — and that she did not sell or rent them. Three years after her death, no one has put a Helen Hill film on YouTube, although friends have uploaded home videos in which she appears.

Thus the “old media” of an artist eulogized as a “visionary Luddite pixilator” continues its life in the “new media” era.[37] Certainly Helen was an exceptional person who modestly made her mark on the world through her films and social actions. The tragic circumstances of her death brought viewers in numbers that DIY filmmakers seldom get.

But Helen’s handiwork also represents a category of media production practiced by many artists, artisans, collectives, and amateurs who do not seek commercial success or professional advancement. With so many producing so much material, scholarship must better account for the millions of moving-image works that exist outside of the mass media. They originate in hundreds of places. In this, the kind of DIY film practice Helen represents is even distinct from the microcinema movement of the past decade. Many microcinemas retain the art house sensibility, in which programmers select films (or more likely videos) to attract connoisseurs. Others emerged with the advent of affordable digital video, seeking to produce independent work and to develop international networks of distribution.[38]

In-person exchanges and backyard viewings remain primary means of circulating the samizdat of small films. However, curated screenings also help sustain DIY media production. As Helen had, her fellow filmmakers continue to curate. Becka Barker, who made Film Farm Dance (2001), in which Helen appears, assembled the exhibition Working on a Plan: Films Inspired by Helen Hill for South Korea’s 2008 Experimental Film and Video Festival in Seoul. Courtney Egan wrote that her “personal response to cultivating local work after the storm” was to curate locally-made videos about the flood, including three annual programs for the New Orleans International Human Rights Film Festival (2006-08).[39] Many other screenings related to Katrina’s impact on the Gulf Coast have been assembled, often placing the amateur video alongside professional documentaries and art pieces. These not only memorialize, they also build preservation consciousness. The Helen Hill film project has been joined by large-scale institutional efforts, such as the Hurricane Digital Memory Bank, and individual ones. Blaine Dunlap, a veteran documentary filmmaker and a video artist in New Orleans, knew Helen well. After a childrearing hiatus, encouraged by her frequent little “bring a movie” events, he resumed shooting — though not until the Katrina evacuation and aftermath. Responding to the enormous losses, he formed Preservista, a full-time venture devoted to “identifying and preserving the work of independent videomakers.”[40]

Conclusion

Saying that Helen Hill represents a large but largely ignored community of alternative media artists does not diminish the exceptional personal impact she had on many people, both in and out of the film world. Her legacy should be celebrated, as Snowden Becker of the Center for Home Movies puts it, for “the great big little thing” it is. Her handprints are visible in many places, but especially in New Orleans. Media coverage and personal accounts reiterate that identity. “Helen was emblematic of New Orleans — a radiant bundle of energy, creativity, and good cheer,” David Koen said in a national radio commentary. In his departing open letter to residents of the city, Paul Gailiunas wrote: “Helen loved New Orleans with a great passion. She was content only when she was in New Orleans, walking among the old shotgun houses, admiring the morning glories and magnolia trees and Spanish moss, listening to WWOZ, straining to catch a Zulu coconut, marching her pot-bellied pig in the Krewe du Vieux, bringing visitors to the Mother-in-Law Lounge, and cooking vegetarian versions of famous Creole dishes.”[41]

Add to this list of her NOLA loves, making home movies, filming parts of the city that escaped touristic views, and teaching her Louisiana neighbors and NOCCA students how to make their own films. Her open house nurtured a creative culture. “I certainly met a lot of the participants of the DIY network,” Courtney Egan confirms, “in Helen’s backyard!” Profiles of Helen and Paul invariably include admiring descriptions of an inspirational couple, such as Jason Berry writing “Gailiunas and Hill were radical humanitarians with a contagious joie de vivre.” Talking with those who knew her, one hears beatific depictions and stories that begin “She changed my life,” and conclude “. . . although I only met her that one time.” I would think these reports of a New Orleans saint were idealized because of her passing — but for the fact that people spoke of her in this way during her lifetime.[42]

The narrative of Helen’s life and the power of her work have become interwoven with Katrina’s. The ability of New Orleans media artists to persevere in exile and in return speaks to the force DIY filmmakers can wield. Despite the floods that took much of her work and the incalculable tragedy of her early death, Helen Hill’s legacy continues to inspire good works, anywhere.

Notes

To the many colleagues and friends of Helen Hill who shared and informed this essay, thank you. My deepest gratitude goes to Paul Gailiunas, Becky Lewis, and Kevin Lewis, for their generosity and grace.

Small portions of this essay are derived from my article “In memoriam Helen Hill,” Film History 19.4 (2007): 438-41, as well as text I posted to the English-language Wikipedia entry on Helen Hill throughout 2007-09, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Helen_Hill.

[2] Helen Hill, “Vessel,” poem published in the New Orleans literary journal New Laurel Review 18 (1993), cited in e-mail from Becky Lewis, Nov. 30, 2009. Upperground Show synopsis on VHS Early Films of Helen Hill, 1990-2001.

[3] Dave Barber, “House of Sweet Magic: The Animated Films of Helen Hill,” (Dec. 5, 2009), winnipegfilmgroup.com/content/view.aspx?content=57af558e-3a0a-47d4-9d91-f6d77eddf931. Barber references filmmaker Amanda Dawn Christie’s “Disruptions of Privacy: Frame X as the Next Rupture in a Regional History,” DVD liner notes for FrameX (AFCOOP, 2008), www.amandadawnchristie.ca/Writ_Disrupt.htm, in which Christie writes of Hill’s influence. Other praise for her impact on Canadian animation include: Christina Jung, “Interview with Filmmaker Leslie Supnet,” Schema Magazine [Toronto], Nov. 9, 2009, www.schemamag.ca/indepth/2009/11, and Adam Klassen, “The Absurd and Whimsical World of Helen Hill,” The Uniter [Winnipeg], Dec. 3, 2009, http://uniter.ca/view/2542.

[4] “Remembering Helen Hill,” The Coast [Halifax], Jan. 3, 2008, www.thecoast.ca/halifax.

[5] Philip Hood, “Helen Hill’s Recipes for Disaster PDF,” Frameworks listserv, Feb. 20, 2007, www.hi-beam.net/fw/fw34/0632.html. Recipes for Disaster (2005 edition) is part of “Public 16’s Cinema Texts,” www.angoleiro.com/cine_texts_recipes_for_disaster_hill.pdf. With a grant from the Maxine Greene Foundation for Social Imagination, the Arts & Education, the 2008 Orphan Film Symposium distributed 300 reproductions of the booklet. Helen’s friend (and fellow filmmaker) Ellie Lee generously loaned her first-generation copy for the reproduction.

[6] Timecode: NOLA Helen Hill Interview (Aug. 2003), posted Feb. 10, 2008, youtube.com/watch?v=o7ReG3l_9fM.

[7] Nowe Miasto Housing Cooperative, http://nowemiastonola.org.

[8] “Killings Bring the City to Its Bloodied Knees,” Times-Picayune, Jan. 5, 2007.

[9] See the Web pages Gothtober.com/archive and Hurricanearchive.org/object/12304.

[10] TheAxeintheAttic.com Web site includes a trailer that begins with the Linda Dumas moment. The film’s credits include the attribution “Home Movies: Linda Dumas.”

[11] Michael Mizell-Nelson, “Not Since the Great Depression: The Post Katrina Documentary Impulse and New Media,” http://media.nmc.org/2007/11/michael-mizell-nelson.mp3. In this talk, he refers to Courtney Egan as “a real force in video production in New Orleans.”

[12] Benjamin Chappetta, “Katrina.wmv,” Hurricane Digital Memory Bank (Jan. 27, 2006), Hurricanearchive.org/object/1694.

[13] The media linking the cases of Helen Hill and Dinerral Shavers was immediate, beginning with the front page of the local newspaper: “Killings Bring the City to Its Bloodied Knees,” Times-Picayune, Jan. 5, 2007. Also significant were activist-attorney Billy Sothern’s New York Times op-ed, “Taken by the Tide,” Jan. 10, 2007; Jacqueline Bishop, “Art and Death in New Orleans,” News and Notes, National Public Radio (NPR), Jan. 9, 2007; and Lisa Haviland, “Don’t Stop the Music: A Look at How Two Murders Moved a Community,” Antigravity [New Orleans], Feb. 2007, 10-11. National long-form coverage included: “One Year Later, New Orleans Grieves for Artists,” twenty-minute feature by Noah Adams, All Things Considered, NPR, Dec. 25, 2007; “Storm of Murder,” 48 Hours Mystery, CBS News, Oct. 13, 2007, updated Aug. 14, 2008, (cbsnews.com/stories/2007/10/09/48hours/main3348928.shtml); “After the Storm,” The 5th Estate, CBC News, Oct. 29, 2008 (cbc.ca/fifth/discussion/2008/10); and “Unknown Helen Hill Killer,” America’s Most Wanted, Fox Television, Sept. 15, 2007, updated Jan. 12, 2008, and Feb. 14, 2009 (amw.com/fugitives/case.cfm?id=42393); and Karen Dalton-Benina, “Free at Last,” Huffington Post, Feb. 21, 2008, huffingtonpost.com/karen-daltonbeninato/free-at-last-second-liner_b_87912.html. See also, Billy Sothern, Down in New Orleans: Reflections from a Drowned City (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), 307-08.

The Hill-Shavers linkage was also immediate in parts of the scholarly community. At the University of California Santa Barbara, Prof. Janet Walker’s graduate seminar, “History, Memory, and Media,” began with a January 6 screening of When the Levees Broke. When PhD student Regina Longo pointed out the January 4 murder, Walker had her present on the subject the following week. Longo had seen Helen’s presentation at the 2006 Orphan Film Symposium.

“I just spent two hours presenting on Helen and her work,” she wrote. “I played the audio recording of Helen from the Orphans 5 website, as we talked about the notion of testimony and ‘listening to silence.’ The main thrust of this class is traumatic memory and its cinematographic representation and I chose to recognize the silence as the absence of imagery (her films) at that moment, rather than the absence of her voice.” Regina Longo, e-mail, Jan. 13, 2007.

Other excellent accounts of Helen’s life and its impact on New Orleans include Phil Nugent, “An American City: New Orleans, Helen Hill and Me,” The High Hat 8 (Winter 2007), thehighhat.com/misc/008/nugent_helen.html; John Clark, “Remembering Helen Hill,” Fifth Estate (Spring 2007), republished in the international libertarian journal Divergences May 14, 2007, http://divergences.be; an epic-length biographical poem by activist-artist (and member of The Fugs) Edward Sanders, “Ode to Helen Hill,” Woodstock Journal (2007), woodstockjournal.com/pdf/helenhill.pdf; and the documentary Helen Hill: Celebrating a Life in Film (South Carolina ETV, 2007).

[14] For a genealogy of the term orphan film see Dan Streible, “The Role of Orphan Films in the 21st Century Archive,” Cinema Journal 46.3 (Spring 2007): 124-28; “The State of Orphan Films,” The Moving Image 9.1 (Spring 2009): 1-13.

[15] Emily Cohen, who attended the Mead Festival screening published “The Orphanista Manifesto: Orphan Films and the Politics of Representation,” American Anthropologist (Dec. 2004): 719-31. She describes orphanistas as “a growing apocalyptic [?] cultural movement of film preservationists,” who “reshape and reproduce cultural memory and heritage” by reviving abandoned films.

My 2001 symposium greeting at the University of South Carolina was done in part because archivist-filmmakers from Cuba and Mexico were special guests. A short video followed, using footage from USC’s Fox Movietone News Collection (MVTN 0-282 Dedication of “Park Row”) filmed on the Fox lot in Hollywood, January 27, 1928. An actor impersonating Leon Trotsky addresses us in untranslated Russian. The deliberately mistranslated English subtitles I devised with Michael Conklin concluded with the faux Trotsky saying to the South Carolina audience “Orphanistas, I salute you!” To my surprise, the dean of liberal arts then concluded her salutation to the audience with the same phrase.

[16] “The Anarchivists’ Manifesto,” Alaska Moving Image Preservation Association, AMIPA.org/images/manifesto.pdf. The first announcement was “Anarchivist Alert,” posted to the AMIA-L listserv, Nov. 8, 2000. AMIPA’s technical director, Bob Curtis-Johnson, was the prankster behind the manifesto. He credits AMIPA co-founder Francine Lastufka Taylor and “citizen of the world” William O’Farrell with using the term anarchivist in the late 1990s. He describes the term as part of the DIY mindset, which advocates archival partnerships to get preservation work done “by any means necessary.” See other AMIA-L postings by Bob Curtis-Johnson: “The end of motion picture film manufacture???” Aug. 26, 2003; “World’s a mess,” Apr. 24, 2003; and “Effect of security screening at airport on videotapes,” Jan. 29, 2003, as well as AMIPA Staff, “Anarchivist Alert!” Nov. 2, 2001.

[17] Kara Van Malssen, Disaster Planning and Recovery: Post-Katrina Lessons for Mixed Media Collections, master’s thesis, New York University, 2006. See also Kara Van Malssen, “Preserving the Legacy of Experimental Filmmaker Helen Hill,” SOIMA [sound and image] in Practice, on-line publication for the Sound and Image Collections Conservation program, initiative of the International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (2008), http://soima.iccrom.org.

[18] Dwight Swanson, e-mail to Helen Hill, May 20, 2006.

[19] Dwight Swanson, e-mail, Aug. 15, 2006.

[20] Think of Me First as a Person, a film by George A. Ingmire III and Dwight L. Core, Sr., DVD, Miabuelo Productions, 2008. The disk includes commentary by Tom De Smet (who supervised the restoration at Haghefilm) and curator Mike Mashon (Library of Congress), as well as the short documentary My Favorite Child (2007), showing Dwight Core Jr. at age 47, intercut with much of the footage from Dwight Sr.’s film.

[21] Brian Graney, “HMD Report: New Orleans, Louisiana,” Aug. 16, 2006, homemovieday.com/news. Kalypso’s New Orleans (Mar. 13, 2006), youtube.com/watch?v=Y18ijTPfBME.

[22] The Center for Home Movies was founded by five members of the new cohort of professionally trained moving image archivists: Dwight Swanson (an archival consultant, working at Appalshop in Whitesburg, Kentucky), Katie Trainor (now film collections manager at the Museum of Modern Art), Snowden Becker (archivist at the Academy Film Archive, next a doctoral candidate at the University of Texas, Austin), Chad Hunter (George Eastman House), and Brian Graney (UCLA Film and Television Archive). WFPF is administered by the advocacy organization New York Women in Film and Television. See also Center for Home Movies, 2008 Annual Report, centerforhomemovies.org.

[23] Audio recordings of John Canemaker’s remarks of March 26, 2008, and most other talks given at the 6th Orphan Film Symposium are available as MP3 files at www.nyu.edu/orphanfilm/orphans6.

[24] Thomas Little credits Helen Hill in two videotaped interviews: Timecode: NOLA Thomas Little Chicken Shit Interview (posted Feb. 10, 2008), youtube.com/watch?v=o7ReG3l_9fM; and Timecode: NOLA Thomas Little Lisa Van Wambeck Interview (Feb. 11, 2008), youtube.com/watch?v=WUUdfVSlolw&feature=youtube_gdata.

[25] Pete Sturman performed under the name Pistol Pete and sang with Rayna Hickman (under the name Rayna Dae). Lauren Heath, Erin Curtis, and Mike Johns, Orphan Ist. (2006), viewable at http://video.google.com.

[26] Helen’s films also pose another preservation conundrum. Five of her early films — Upperground Show, 5 Spells, No Smoking in the Theater, Fast Fax, and I Love Nola — are only known to survive on a VHS compilation. Even these are dubbed from other videotape copies. Winsome Brown (another filmmaker/friend of Helen) loaned me her copy of Early Films of Helen Hill, 1990-2001. Ben Moskowitz (NYU Libraries, preservation department) transferred that VHS to a DigiBeta “master” in November 2009. The technical work was done professionally, but arrangements were DIY, accomplished outside of institutional workflow. Harvard Film Archive now holds the DigiBeta as a surrogate preservation master.

[27] Paul Gailiunas, “For My Poor, Sweet Wife, Fix New Orleans,” January 26, 2007. He submitted the letter to the Times-Picayune, but it appeared only on-line and circulated freely on the Internet.

Confusingly, the anarchist collective known as Crimethinc, reworked William Powell’s infamous The Anarchist Cookbook (New York: L. Stuart, 1971) as Recipes for Disaster: An Anarchist Cookbook, A Moveable Feast (Olympia, WA: Crimethinc. Workers’ Collective), but not until 2004, three years after the Helen Hill Recipes for Disaster cookbooklet. Other Crimethinc. members issued DIY ‘zines, such as D.I.Y. Guide II (Atlanta, 2002).