Note: This is a draft in progress, with additions, corrections, and other edits appearing as they become available.

What I thought would be an addendum to an earlier post, “Capturing Venus in Motion and Filming an Eclipse in the 19th Century,” expanded into territory I did not expect: four women were involved with the operation of motion-picture cameras during solar eclipses in 1898, 1900, and 1901. Gertrude Bacon, Ada Ardley Maskelyne, Annie Russell Maunder, and a certain “Mrs. Ireland.” Each used one or more machines from the London magician-inventor/s John Nevil Maskelyne (1863–1924) and/or his father John Nevil Maskelyne (1839-1917). All were part of eclipse expeditions organized by the British Astronomical Association (B.A.A., which Bacon and her father and Maraunder and her husband were charter members) . Considering these narratives in the wake of a symposium on counter-archives, we can consider how they often saw the solar events from colonized places within “the Empire on which the sun never set.”

Between their ventures in India 1898 and Mauritius 1901 came the historic Maskelyne recording in the United States — the film we can still watch. On May 28, 1900, a custom-made motion-picture camera recorded a total eclipse of the sun as seen from Wadesboro, North Carolina. When the Royal Astronomical Society (UK) rediscovered a fragment of film, the BFI National Archive restored it in 2019. It likely had not been seen in more than a century.

Solar Eclipse (Nevil Maskelyne [Jr.], May 28,1900) from 375 frames of 35mm film

More than a footnote: It’s not entirely certain which Maskelyne/s developed and operated the camera. The father? the son? both? . . . the son’s wife? One can say accurately Nevil Maskelyne (the son) made this film, but there’s more to the story.

The Journal of British Photography noted shortly before the film was shot, “the kinematograph” would “be worked by Mr. and Mrs. Maskelyne.” At a B.A.A. meeting, Gertrude Bacon described the planned division of labor among “four ladies and four gentlemen” “Mr. and Mrs. Nevil Maskelyne would (1) direct the telescopic kinematograph upon the corona throughout the totality and (2) expose a long film in an ordinary kinematograph camera directed towards a chosen point of the landscape” before, during, and after totality.

The leader of the B.A.A.’s American expedition, John M. Bacon, said whilst Nevil was scrambling to assemble the camera before the eclipse, Ada Mary Ardley Maskelyne “took over the management of a clock-driven actinometer [measuring solar radiation] which at my desire her husband had designed.” (The Total Solar Eclipse 1900.) Neville told the journal the device was important to synchronize with photography because it could confirm a phenomenon photo-documented by Gertrude Bell during the 1898 eclipse: when an eclipse ends, sunlight returns “much more quickly than [when] it dies away as totality approaches.” Not much more about his wife Ada’s career is yet known to me, except that as Ada Ardley she performed on stage with her husband and father-in-law in London’s Egyptian Hall in the 1880s.

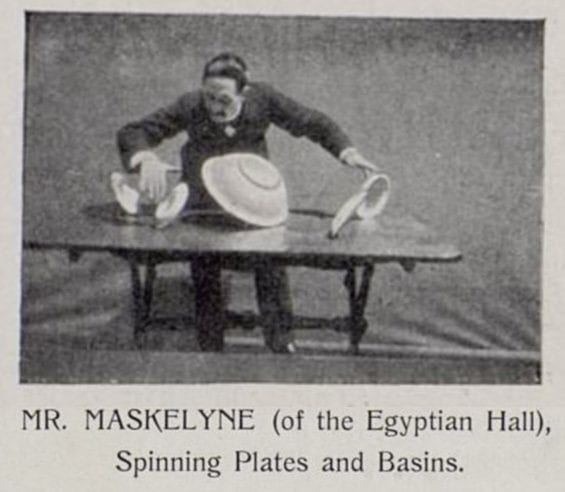

More confusing is the shifting identity of the attributed filmmaker. Father and son had the same name but were seldom identified as senior and junior in the press or in subsequent historical writing (with exceptions such as this 1891 U.S. patent application). The elder was a famous stage magician, theater manager, author, and inventor, who used the names Nevil, John Nevil, J. Nevil, and J. N. Maskelyne. His son, usually but not always known as Nevil, also became a well-known magician and accomplished inventor. Both were typically identified as “of the Egyptian Hall.” Both were pioneer exhibitors of motion pictures and held patents on film technologies. In 1896, their show business partner Robert Paul filmed the father in an act he had been doing on stage for thirty years. A frame survives in Catalogue of Paul’s Animatographs & Films (1901/03).

And 45 frames were printed as film strips in C. Lang Neil’s book The Modern Conjurer (1903). John Helvin reanimated them in 2009 as Film of J. N. Maskelyne Plate Spinning.

They resembled one another and died only a few years apart, so conflation is understandable. The pair are now adequately disambiguated on Wikipedia, but accounts of the eclipse films and some histories of Victorian-Edwardian popular culture attribute actions to one Maskelyne when both were involved. Or to one when the other was the person responsible.

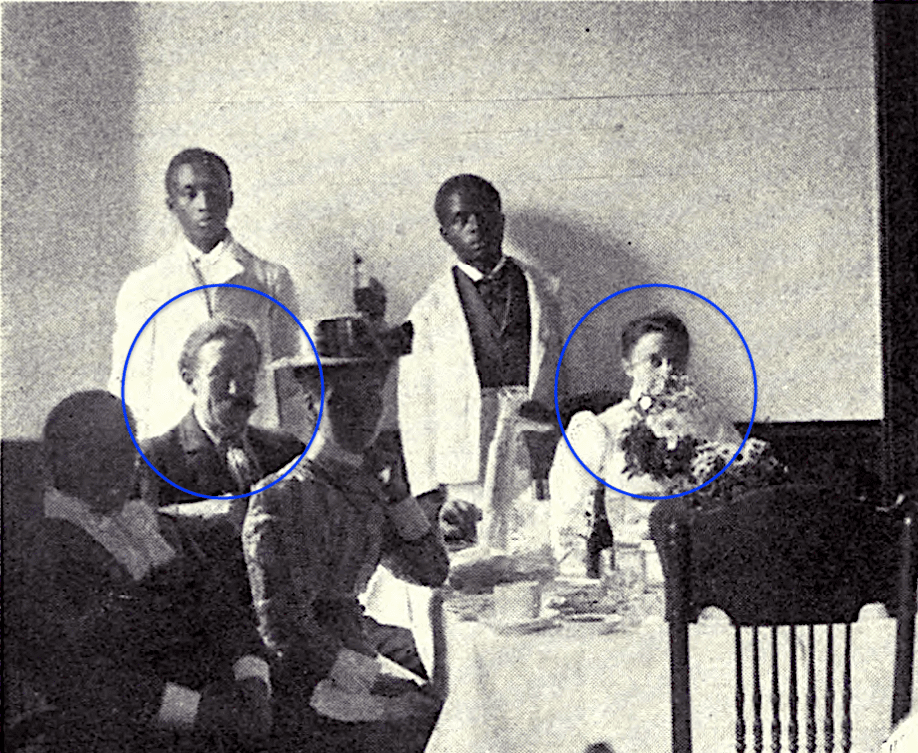

BFI curator Bryony Dixon, writing about the restoration in Sight and Sound (August 2019), specified it was “Maskelyne Jr” who took the solar eclipse pictures. Extensive British press coverage followed his trip to the United States. Corroboration is seen in a photograph (below) showing Mr. and Mrs. Maskelyne in Wadesboro in May 1900. He appears more like a person of 36 years than 59 (as the senior Maskelyne would have been). His face resembles a ca. 1903 photograph of the junior.

[Do they resemble Benedict Cumberbatch? For several years, he has been attached to a feature film in which he will star as Jasper Maskelyne, son of Nevil Jr. War Magician is an adaption of a book about “British illusionist Jasper Maskelyne, who used magic to defeat the Nazis in World War II” (really). And speaking of outer space, sometimes Star Wars writer and director Colin Trevorrow is to helm the Maskelyne biopic. Here we can add he is a graduate of NYU Tisch School of the Arts.]As to the 1900 solar eclipse film itself: This BFI video copy shows the totality of the eclipse for 33 of its 69 seconds. Observers in Wadesboro that day measured the actual duration of the totality as nearly 90 seconds. Maskelyne was undercranking (as it would later be called), condensing time by slowing the speed at which frames of film were exposed. When projected, the motion would appear accelerated (depending on the speed of projection).

“Mr. and Mrs. Walter Maunder” (our Annie Russell Maunder) reported on Maskelyne’s “kinematograph” frames with exactitude.

The instrument was run for about 5 3/4 minutes, commencing some 25 seconds before totality, and running for nearly 4 minutes after totality was ended. In all 1187 exposures were made, 87 before totality, 299 during totality, and 801 after. (The Total Solar Eclipse 1900, p. 143)

These numbers are approximately consistent with the BFI’s 375 frame count and running time. The video unfurls some three times faster than did the observed eclipse. (To further confuse the present assessments of speeds and father-son inventors: in 1897, Maskelyne Jr. developed a camera and projector for high-speed photography. See magicians by Deac Rossell in Encyclopedia of Early Cinema.)

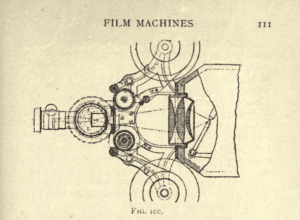

The elder Maskelyne had a long-running presence as a performer at London’s Egyptian Hall, which he also managed. With magician David Devant, he debuted motion pictures there in March 1896 using a projector of Robert Paul’s design (two days before Paul could debut it himself elsewhere). However they formed a partnership rather than commercial rivalry. In 1897, Paul recruited him as a co-director of his company and advertised acquisition of “a New Model of the Animatographe, invented by Mr Nevil Maskelyne.” (Was this the son?) In May 1896, J. N. Maskelyne (the father?) received a British patent for “An improved apparatus for securing, or exhibiting in series, records of successive phases of movement.” He/they called this motion-picture camera and projector the Mutagraph. It was well received but not marketed to others.

Although the camera taken to film the eclipses of 1898, 1900, and 1901, was not referred to in the press as a Mutagraph, Henry Hopwood’s technical manual Living Pictures (1899) describes the design of “Maskelyne’s Mutagraph” and adds “It was an instrument of this kind which was taken to India in order to secure a view of the late total eclipse of the sun; sad to say, the film disappeared on its journey home, and neither the Wizard of Piccadilly nor a reward of fifty pounds has yet succeeded in bringing the errant eclipse to light.”

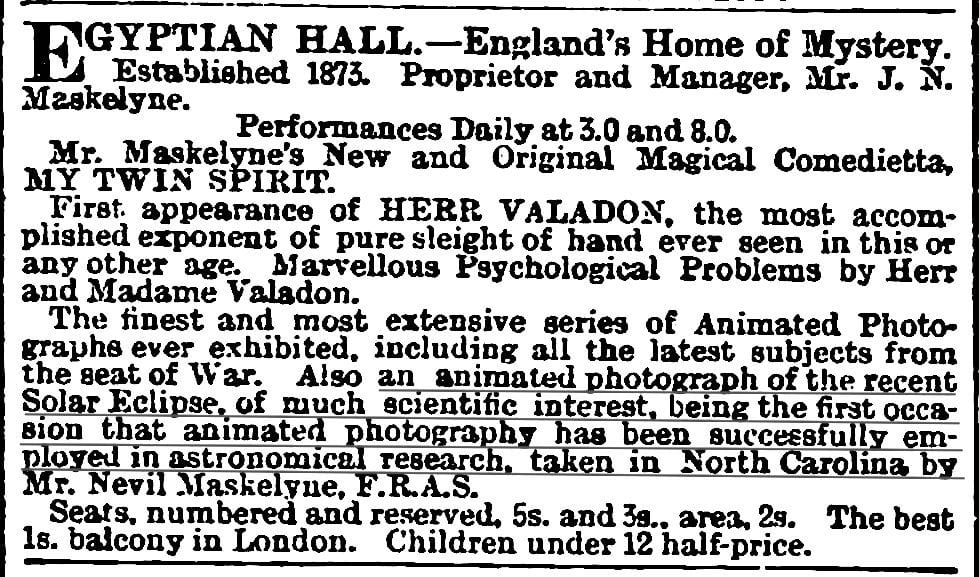

For several months in 1900-01, this advertisement for the solar eclipse film ran in London newspapers.

This clarifies that “Nevil Maskelyne” refers to the son, who shot the film, while “J. N.” is the father who remained in London and exhibited it. Consistent with this, the filmmaker who reported frequently to the British press and professional journals used the byline Nevil.

Although the film circulated little beyond the Egyptian Hall, prominent American astronomer David P. Todd obtained a 35mm print, which he had projected during his lecture at the Brooklyn Institute in November 1900. Todd himself made 100 still photographs in 51 seconds viewing the same May 28 eclipse from Tripoli. These glass slides were not projectable as motion pictures but were not so distant from Maskelyne’s recording at 4 frames per second. Having made serial photographs of the transit of Venus in 1882, Todd expressed hope of getting a Biograph (his term) camera for his 1900 expedition, but did not.

The failure of eclipse films became down right topical. Just a week after the event, American Mutoscope and Biograph Co. made How He Saw the Eclipse, a.k.a. How He Took the Eclipse (June 5, 1900). Its catalog synopsis described the now-lost film: “A good comedy picture, showing how a small boy interrupted an astronomer’s vision, by pouring a bucket of water into the telescope.”

To achieve the apparent milestone of cinematography, Nevil Maskelyne said he worked specifically to build a camera that could record an entire eclipse when coupled with a telescope. However, two curious points remain about the uniqueness of an apparatus needed to capture the eclipse in motion. As Maskelyne serially reported in published accounts, he found out while en route from London to North Carolina that his painstakingly built kinematograph did not make it aboard. He set about building it anew while in New York.

Fellow eclipse photographer John Bacon wrote that the “optical part” of Maskelyne’s instrument did not get shipped from London, but that Maskelyne somehow fabricated a replica of the novel apparatus a few days before the May 28 event. Bacon described his Carolina traveling companion as the “unrivaled mechanician” and “genius” from the Egyptian Hall.

Further, with less ado, another motion picture of the 1900 eclipse was made. No less a British film pioneer than Cecil Hepworth filmed the eclipse from Algiers. Annie and Walter Maunder, who were also in Algiers, noted that Hepworth and his kinematograph were in a B.A.A. group apart from theirs. London newspapers reported he “started his cinematograph ten minutes before totality,” and “took nearly three thousand five hundred photographs of the eclipse.” (“The Solar Eclipse, Photographic Records,” London Standard, June 1, 1900, p. 3). If true, Hepworth’s recording was triple the length of Maskelyne’s, though totality in Algiers was nearly half a minute shorter in duration. In his 1951 memoir, Hepworth describes using an “apparatus I had carefully constructed at home” for the occasion: an electric battery and “motor to drive the camera steadily at slow speed.” “I secured an excellent picture of the beautiful corona with enough of the before-and-after to give it point” (48-49).

“At Algiers I filmed the solar eclipse of May, 1900.” Hepworth, Came the Dawn (1951), unnumbered plate after page 24.

“At Algiers I filmed the solar eclipse of May, 1900.” Hepworth, Came the Dawn (1951), unnumbered plate after page 24.

Hepworth’s solar eclipse footage screened alongside Boer War films at the London Hippodrome. (Lantern Record, July 6, 1900). By year’s end, 35mm prints of it were being sold second hand.

In 1898, Nevil Maskelyne loaned his device to the Bacon family, amateur but learned British astronomers traveling to northeast India to observe and study a highly publicized eclipse.

A second group, funded by the Joint Permanent Eclipse Committee of the Royal Society and Royal Astronomical Society, mounted a major expedition to India’s west coast. Renowned astronomer Norman Lockyer, leading his eighth such scientific voyage, got support from the British navy: a warship, materiel, and 150 volunteers. Among them was a marquess who contributed two cinematograph cameras to the extensive photographic inventory. The make of these “kinematographs” is not known, but they failed where Maskelyne’s animatograph succeeded.

However, nothing is known to survive from these efforts. We could list these three lost films in a filmography of early cinema’s recordings of celestial bodies.

• [Solar eclipse viewed from Buxar, India] (Gertrude Bacon and John Bacon, 1898) Eclipse Committee, British Astronomical Association;

• [Solar eclipse viewed from Viziadrug, India]; and

• [Landscape amid eclipse shadows at Viziadrug] (Lord Graham, 1898) Eclipse Expedition, Royal Astronomical Society

In press reports and in the book Recent and Coming Eclipses (2nd. ed., 1900) Lockyer referred to two “kinematograph” machines, one to film the eclipse, the other its shadow. Each had its own crew. Initially, his press dispatches claimed “Lord Graham’s cinematograph work has proved quite successful.” (Morning Post, Jan. 24, 1898, p. 1.) However, “one instrument of French manufacture [Pathé?], was found to work very unsatisfactorily,” but an engineer “put the instrument into working order.” Eventually Lockyer reported 8,000 frames were exposed, but a crack in the camera allowed too much light in, fogging the images “beyond any use.”

Meanwhile, the amateurs of the British Astronomical Association succeeded. Gertrude Bacon, her brother Fred, and father John reported from Buxar that their film of the eclipse was recorded using an “animatograph.” The trade name accurately specified the invention of Robert Paul, who indeed collaborated with Maskelyne, purchasing the rights to his adaptations of the camera.

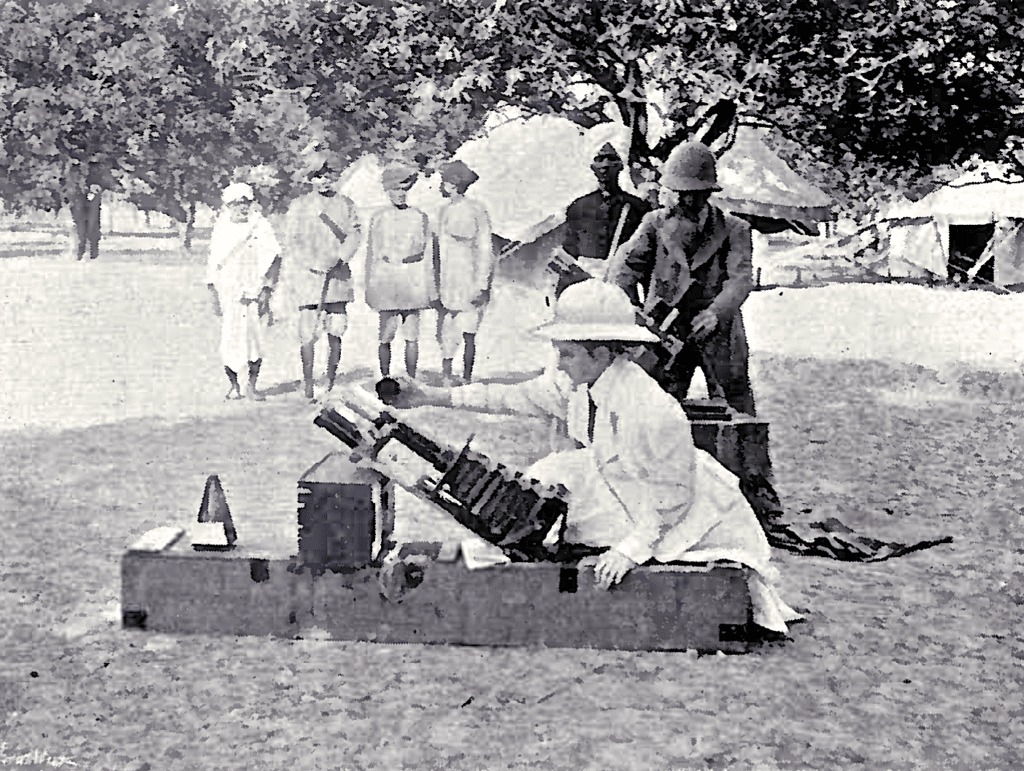

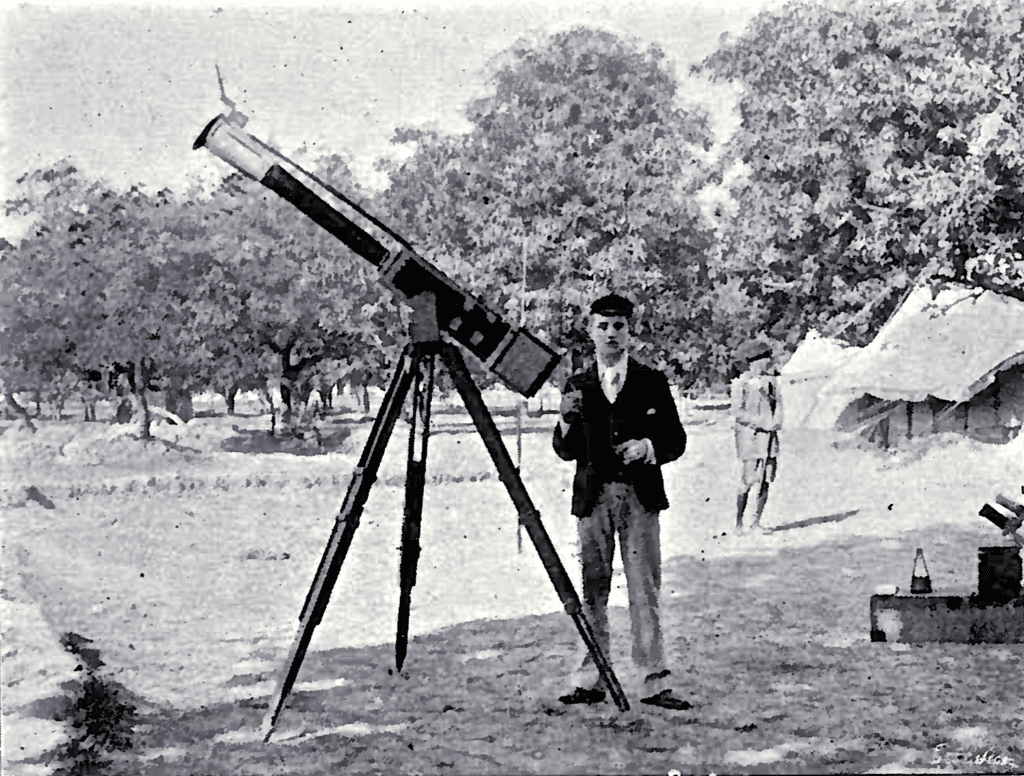

In the Buxar expedition’s published report John Bacon wrote: “The heaviest and most important instrument was undoubtedly the animatograph telescope, specially designed for the expedition by Mr. Nevil Maskelyne. As a piece of delicate and complex mechanism this apparatus demanded much care and manipulation, and a certain period of each day was set apart for requisite practice. At intervals, too, during the voyage, a practical use was made of its capabilities. A number of spare films [unexposed stock] had been supplied by Mr. Maskelyne, in addition to one of special length for the eclipse; and with the consent and ready co-operation of our genial captain several photographs of animated scenes on board ship were secured.” (33).

However, when the ship carrying the Bacon films arrived in England, the can containing the eclipse footage was missing. In public lectures, John Bacon showed photographs taken by Gertrude and Fred, but told of the disappointment when discovering their eclipse film had been lost, likely stolen.

But the Bacons persisted. In 1900, they accompanied Maskelyne to North Carolina where he filmed the solar eclipse. Gertrude “worked successfully four cameras simultaneously” with “special light-gathering lenses” her father told the local press. (“The Sun Eclipsed,” Messenger and Intelligencer [Wadesboro], May 31, 1900.) She was also becoming a celebrity for her pioneering aeronautics.

Her brother snapped this portrait of Gertrude posing with Maskelyne. The Bacons had lost their chance to show the world’s first film recording of an eclipse but they were on site with the cinematographer who repeated the feat.

A year later two other women appeared on the eclipse-filming scene. One an established science photographer, the other unknown.

On May 19, 1901, a Reuter’s news item about the British expedition viewing the eclipse on the island of Mauritius noted casually “. . . and Mrs. Ireland drove the Maskelyne kinematograph.” (“The Eclipse of the Sun,” London Observer). A British Astronomical Association report later connected the moment to previous mishaps with eclipse footage. Members at a meeting discussed how they “might hope at a future meeting to see a kinematographic view of the eclipse, as the [Reuters] telegrams went on to show that a successful kinematographic film was taken by Mrs. Ireland, with Mr. Maskelyne’s famous instrument.” They “hoped that no contretemps would occur on this occasion as happened in India, when the film was lost, and in America, when the kinematograph was lost.” (Journal of the BAA, vol. 11, no. 8, May 29, 1901, p. 309. The American film of 1900 was of course not lost, but had been showing commercially for months.)

Who was this camera “driver,” “Mrs. Ireland”? Perhaps the “Mrs Ireland” who the Astronomical and Physical Society of Toronto elected to its membership in 1896? Perhaps not.

A third female member of the society of eclipse-chasing cinematographers reported from Mauritius in 1901, one with a consequential career in astronomy. Annie Scott Dill (Russell) Maunder (1868-1947) was a mathematician who married astronomer Edward Walter Maunder (1851-1928) in 1895. Their research collaborations from 1890 onward included photography of the sun. That year he founded the B.A.A. for amateurs, particularly for women excluded from professional ranks. He and Annie edited its journal. Both published scientific accounts of their 1901 eclipse observations. She gives us a clue as to who “Mrs. Ireland” was, while also revealing what became of the film attributed to her.

As “(Mrs.) A.S.D. Maunder,” she read a paper at a Royal Astronomical Society meeting in 1901. The published version details the scientific and photographic instruments the Royal Observatory crew took to Mauritius. “Mr. Nevil Maskelyne also lent me his kinematograph,” she added. “Management of these instruments during the eclipse was very kindly undertaken by several friends.” She identifies among the personnel “Mr. G. H. Ireland: Kinematograph.” (A Mrs. Ireland is not mentioned. Mister was a member of the Colonial Service on the island.) “The kinematograph gave no result,” Maunder notes dryly, “the film tearing across before totality was reached.”

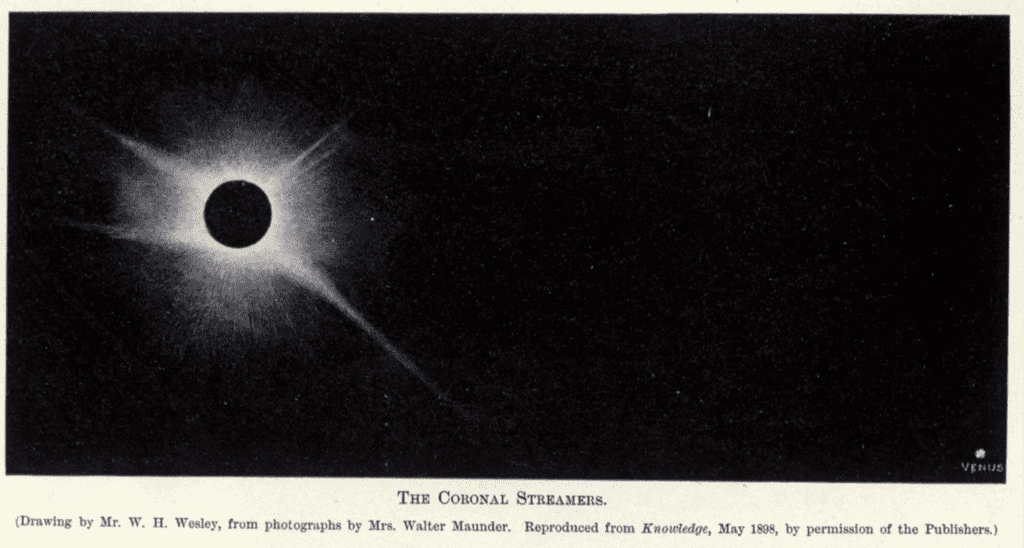

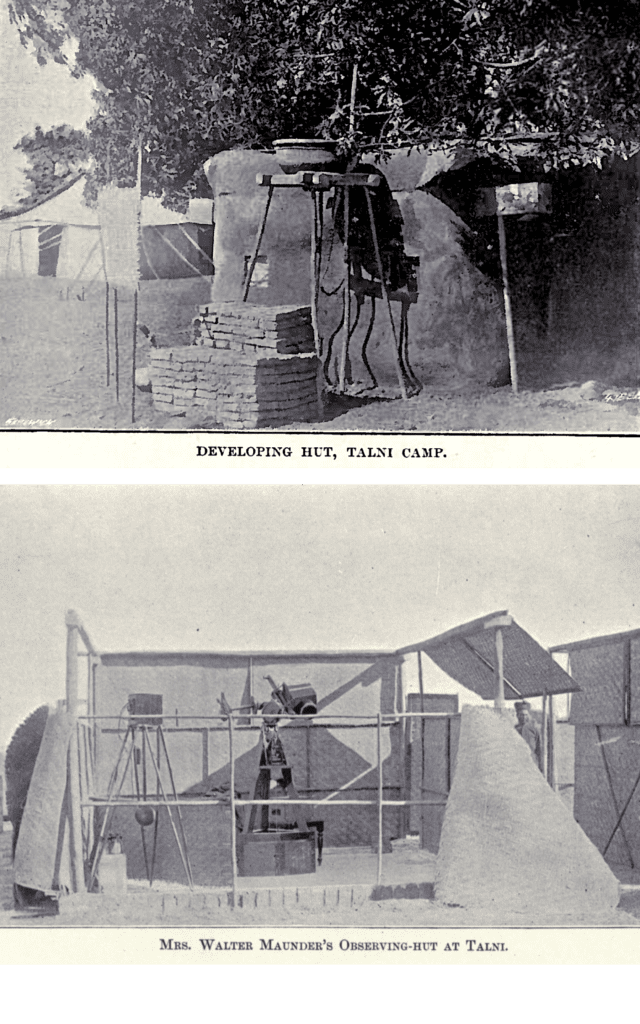

This disappointment aside, Annie Russell Maunder was recognized even early in her career as an accomplished photographer. Using cameras of her own design she took scientifically significant photographs of the 1898 eclipse in India, photo-documenting what had previously only been hand drawn by artists: “coronal streamers.”

In The Indian Eclipse 1898 they recount their trip to the village of Talni (Maharashtra region, west-central India). Annie illustrates her narrative with her own photographs. Here, the make-shift darkroom for the photochemical processing of still photos and the structure built for her observation of the eclipse.

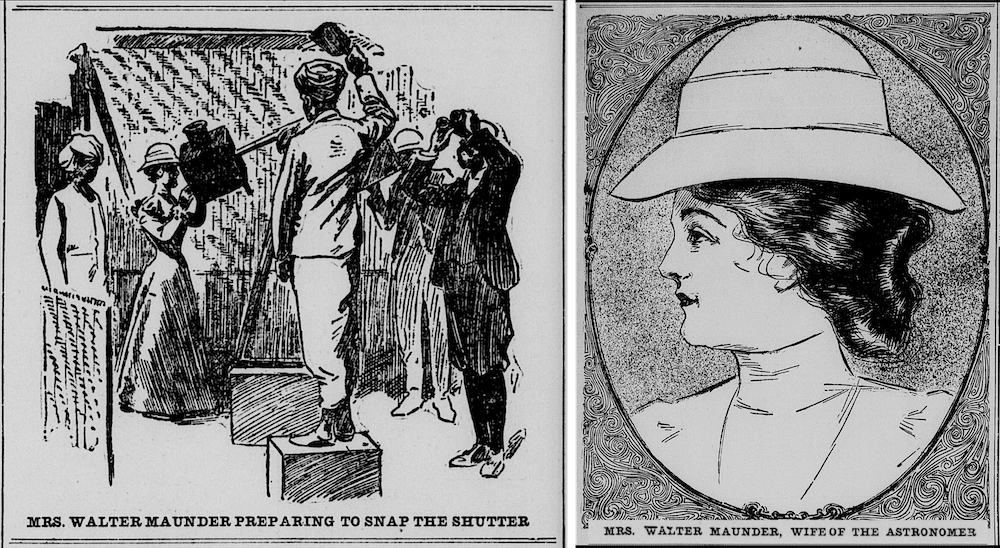

She also provided her account and images to the Hearst press in the United States. The Los Angeles Examiner told of the “plucky and determined” woman breaking into the domain of men of science, emphasizing her role as photographer.

She also provided her account and images to the Hearst press in the United States. The Los Angeles Examiner told of the “plucky and determined” woman breaking into the domain of men of science, emphasizing her role as photographer.

Annie Maunder also published a comparison of her celebrated photograph of the corona with a frame enlargement from Maskelyne’s film. Two images taken at the same moment in time, hers on a glass plate in Algiers, his on a 35mm motion-picture film in the United States.

Addendum (celestial photography as colonialist practice)

“G H Ireland’s bungalow in Mauritius, c.1902.” Photograph from the British Empire & Commonwealth Collection, Bristol Archives, Bristol Museums, UK.

Who was “Mrs. Ireland” who “drove the Maskelyne kinematograph” in 1901?

This is not a photograph of her. But the caption and the unlikely find of this picture of her colonial home and garden conjures up an idea of what the white Europeans from the Royal Observatory might have experienced at the end of the Victorian Era when venturing to that island in the Indian Ocean northeast of Madagascar. A privileged, protected, parasol-and-plantation idyll from which they could cast their gaze and train their cameras upon the celestial bodies far from Earth.

Sources:

Sir Norman Lockyer, “Total Eclipse of the Sun, January 22, 1898, Preliminary Account,” Report on the Solar Eclipse Expedition to Viziadrug (1899);

Sir Norman Lockyer, Recent and Coming Eclipses, 2nd ed. (London: MacMillan, 1900).

Mrs. Walter Maunder, “Solar Eclipse Photographed,” Los Angeles Herald, Mar. 20, 1898.

A. S. D. Maunder, “Preliminary Note on Observations of the Total Solar Eclipse of 1901 May 18, made at Pamplemousses, Mauritius,” read at a joint meeting of the Royal and Royal Astronomical Societies, Oct. 31, 1901, Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, April 4, 1902.

E. Walter Maunder, ed. The Indian Eclipse 1898: Report of the Expeditions Organized by the British Astronomical Association to Observe the Total Solar Eclipse of 1898 January 22 (1899).

E. Walter Maunder, ed. The Total Solar Eclipse 1900 (London: “Knowledge” Office,1901).

Mabel Loomis Todd, Total Eclipses of the Sun, rev. ed. (Boston: Little, Brown, 1900), introduction by David P. Todd.

Alex Soojung-Kim Pang, “The Social Event of the Season: Solar Eclipse Expeditions and Victorian Culture,” Isis 84, no. 2 (1993): 252–77.

Bryony Dixon, “Darkest Hour,” Sight and Sound, Aug. 2019, 15.

“Annie Russell Maunder,” Royal Museum Greenwich website, 2022.

Toni Booth, “Magic and Early British Cinema,” blog, National Science and Media Museum (Bradford, UK), Feb. 13, 2019.